[EN/SK] ‘Homo faber’ by Juraj and Matej Gavula at Július Koller Society

![[EN/SK] ‘Homo faber’ by Juraj and Matej Gavula at Július Koller Society](https://blokmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/homo-faber-9.jpg)

[EN]:

text by Peter Szalay

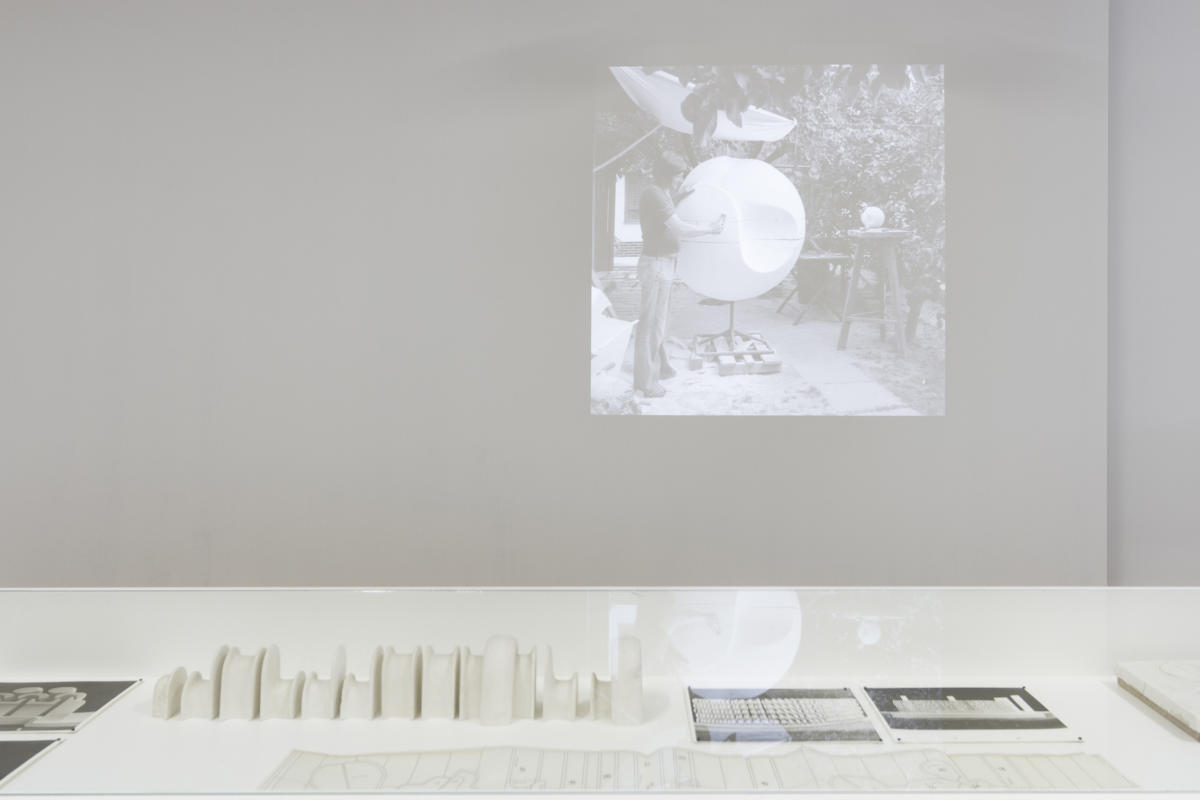

The Homo Faber exhibition reflects the rise and fall of socialist modernism. It tracks the traces of its original construction and present decay, using as an example the sculptures created for hospital buildings. The monumental works of Juraj Gavula, having taken guidance from Václav Cigler’s lessons, is based on the principles of minimalism and organic sculpture. Matej Gavula in a dialog with his father’s archive uncovers the production background of his creative process while his own works comment on the transition of healing spaces from reality to fiction.

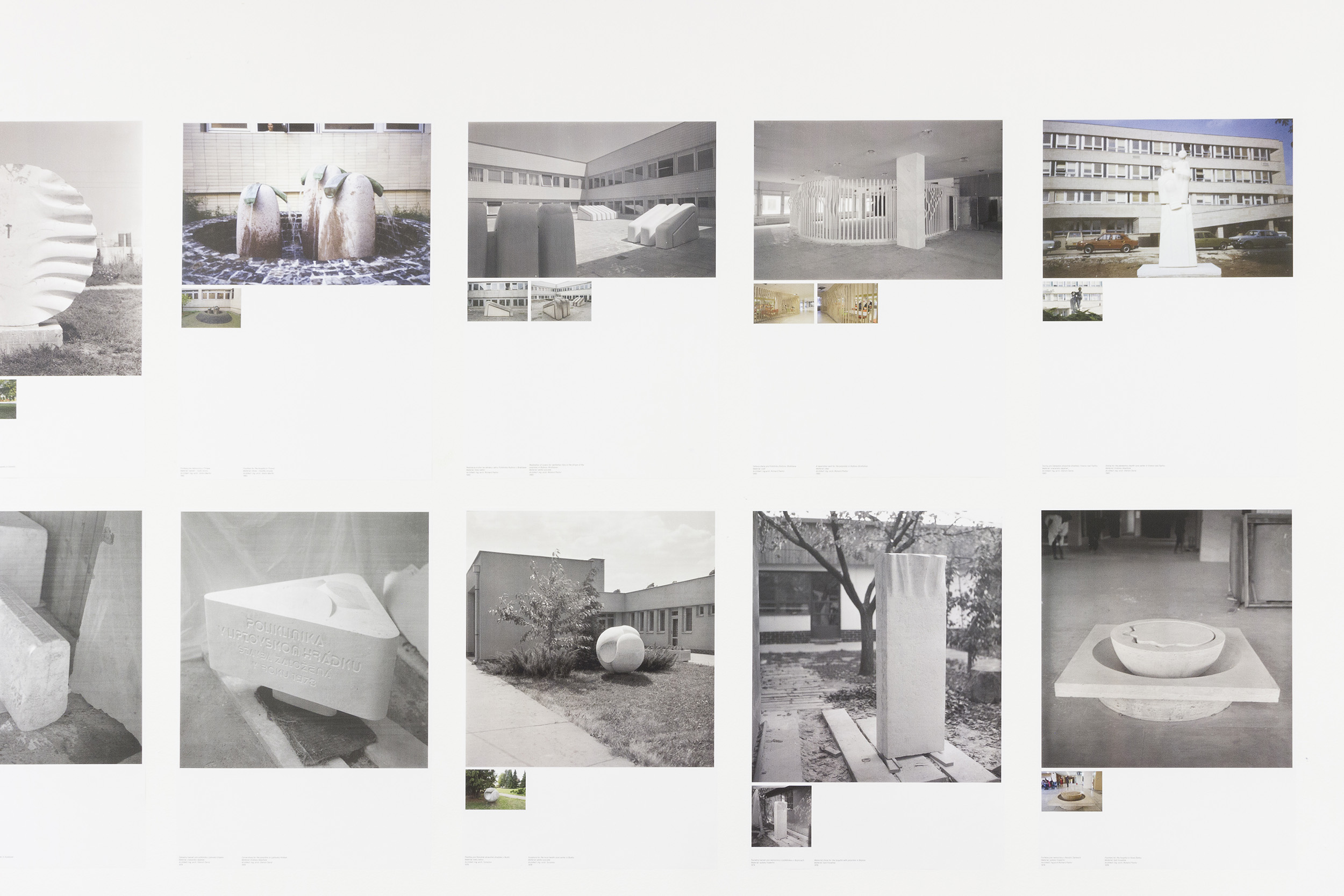

Sculpture in architecture forms a significant part of the sculptor Juraj Gavula’s oeuvre. His minimalist, perfectly processed statues and reliefs of stone or concrete fulfill the role of cornerstones, fountains, walls or covers for technological equipment of buildings, but also stand on their own, autonomously from their architectural hosts. The selection from the archive of Gavula’s works which consists of his realization for medical institutions in the 1970s and 1980s reflects the trajectory of development of the genre which was then referred to as “environment-oriented works”. Art in architecture and in the public space in Slovakia was during these two decades a program part of architectural or building construction production, due not only to the period legislation which prescribed use of a certain part of costs of investment construction for creation of works of visual art, but also to the internal architectural and artistic points of departure of modernism which strove to find new forms of synthesis of various arts.

Beginning in the 1960s, the once closely watched formal side of art intended for architecture stopped being the focus of the expert committees of the Slovak Fund for Visual Arts. The positions previously held by ideological censors were largely assumed by architects, designers and artists who approved individual projects from a mostly pragmatic economic standpoint. With the exception of monuments created for the public space, the themes that prevailed were predominantly “apolitical”, their goal being creation of a harmonic living environment for the new socialist society rather than straightforward Communist propaganda.

An almost metaphorical dimension of the effort to promote the building of socialist welfare was carried by the unusual sculptors’ task of creating cornerstones for public buildings. These objects served as a tool for public presentation or rather the ceremony of commencement of construction of the planned investments and at the same time had the ambition to become permanent heritage, monuments which would preserve the names of its builders for posterity. During the normalization era, hospitals were second only to housing when it came to the most promoted contributions to increase in the quality of life in socialist Czechoslovakia, and the period did indeed witness the most massive construction that ever took place in Slovakia and continues to form the bulk of the country’s health-care infrastructure. For Juraj Gavula, these seemingly uninspiring commissions formed a space for development of his own creative program, his research material, shape reduction and perfection of craftsmanship.

Cornerstones in their very function evoke the archetypal form and Gavula varied it using minimalist means – always as a clear, structurally pure, stable block.

Cornerstones as well as artworks intended for interiors and exteriors were initiated by architecture planners. The selection of the artists and concrete work did not take place by means of competitions or other types of transparent selections but was left to the architect’s discretion. In case of health-care facilities these involved solely architects of the state’s specialized project institute, Zdravoprojekt Bratislava, who grew fond of their cooperation with Juraj Gavula. The collaboration was however for the most part hardly creative, the architects would merely determine the basic localization or type of the artwork and left the rest to the sculptor’s choice.

In his designs, the artist produced mostly variations on his own motifs from his more private oeuvre, rather than attempting a distinct dialog with the architecture. They are essentially inserted objects – aestheticizing elements in the austere utilitarian architecture of the hospitals. His relief walls are nevertheless marked by an almost tectonic architectural quality. Some of his fountains give the impression of models of fantastic landscapes and cities, always using the characteristic shorthand and abstracting reduction of shapes, combining organic natural forms with strict geometry.

Most of Gavula’s works for health-care facilities are currently on the margins of interests of their owners. The fountains lack technical maintenance and water, some of the cornerstones are overgrown with weeds on the decrepit premises of the facilities, others were moved to interiors, or simply dropped to lie somewhere else than their original placement, but are, due in part to the durable materials used, preserved without significant changes. Thus, they mirror the state of disinterest, neglect and inertia with which we currently function.

The exhibition points out not only the need of taking care of artworks from the socialist era, but also seeks to inspires greater general sensitivity in terms of interest in the public space and the infrastructure that benefits all.

[SK]

text: Peter Szalay

Výstava Homo Faber reflektuje socialistický modernizmus v jeho vzostupe a úpadku. Sleduje stopy vtedajšieho budovania a súčasného rozkladu na príklade sochárskych diel pre architektúry nemocníc. Monumentálna tvorba Juraja Gavulu, poučená školením u Václava Ciglera, vychádza z princípov minimalizmu a organickej plastiky. Matej Gavula v dialógu s archívom svojho otca odkrýva produkčné zázemie jeho tvorby a vlastným dielom komentuje prechod priestorov liečenia od reality k fikcii.

Plastika v architektúre tvorí významnú časť práce sochára Juraja Gavulu. Jeho minimalistické, dokonale opracované kamenné či betónové sochy a reliéfy plnia funkciu základných kameňov, fontán, stien či krytov technologických zariadení budov, no pôsobia aj ako diela autonómne od svojich architektonických hostiteľov. Výber z archívu Gavulových prác, ktorý pozostáva z jeho realizácii pre zdravotnícke zariadenia zo 70. a 80. rokov 20. storočia reflektuje trajektóriu vývoja žánru vtedy označovaného ako „tvorba pre životné prostredie“. Umenie v architektúre a verejnom priestore na Slovensku bolo počas týchto dvoch dekád programovou súčasťou architektonickej, či stavebnej produkcie a nevychádzalo to len zo súdobej legislatívy, určujúcej využitie časti stavebných nákladov investičnej výstavby na vznik výtvarného diela, ale aj z vnútorných architektonických a umeleckých východísk modernizmu usilujúceho o nové formy syntézy.

Pôvodne ostro sledovaná formálna stránka umenia pre architektúru od 60. rokov minulého storočia, vypadla z hľadáčika expertných komisií Slovenského fondu výtvarných umení (SFVU). Miesta ideologických cenzorov tu do veľkej miery nahradili architekti, dizajnéri a umelci, ktorí schvaľovali jednotlivé projekty skôr z pragmatického ekonomického hľadiska. Vynímajúc pamätníkovú tvorbu vo verejnom priestore sa presadzovali predovšetkým „apolitické“ témy, ktorých cieľom nebola priamočiara komunistická propaganda, ale vytváranie harmonického životného prostredia novej socialistickej spoločnosti.

Až metaforický rozmer úsilia propagovať budovanie socialistického blahobytu nesie neobvyklá sochárska úloha, tvorba základných kameňov pre verejné stavby. Tieto objekty slúžili ako nástroj pre verejné prezentovanie, či lepšie obrad odštartovania výstavby plánovaných investícii a zároveň mali ambíciu byť trvalým odkazom, pamätníkom, ktorý pre budúcnosť zachová mená svojich budovateľov. V období normalizácie patrili nemocnice po bývaní prirodzene k tým najpropagovanejším príspevkom zvyšovania kvality života v socialistickom Československu a v tomto období aj skutočne prebehla na Slovensku najmasívnejšia výstavba, ktoré dodnes tvoria väčšinu našej zdravotníckej infraštruktúry. Pre Juraja Gavulu boli práve takéto zdanlivo nepodnetné zákazky, priestorom na rozvíjanie vlastného tvorivého programu, jeho skúmanie materiálu, tvarovej redukcie a dokonalého remeselného spracovania. Základný kameň už svojou samotnou funkciou evokuje archetypálnu formu a Gavula ho varioval minimálnymi prostriedkami – vždy však ako jasný, konštrukčne čistý, stabilný blok.

Základné kamene ako aj umelecké diela určené do interiérov a exteriérov boli iniciované projektantom architektúry. Voľba umelca a konkrétneho diela neprebiehala prostredníctvom súťaží či iných transparentných výberov, ale bola ponechaná architektovi. V prípade zdravotníckych stavieb to boli výhradne architekti špecializovaného štátne projektového ústavu, Zdravoprojekt Bratislava, ktorí si obľúbili spoluprácu s Jurajom Gavulom. Do veľkej miery to však nebola tvorivá spolupráca, architekti zväčša určili len základnú lokalizáciu či typ umeleckého diela a ostatné ponechali na voľbu sochára.

Pri návrhoch pre architektúru výtvarník varioval predovšetkým vlastné motívy z komornej tvorby, než by sa usiloval o výrazný dialóg s architektúrou. Sú to v podstate vložené objekty – estetizujúce prvky v utilitárne strohej architektúre nemocníc. Napriek tomu v jeho reliéfnych stenách badať až architektonickú tektonickosť. Niektoré jeho fontány pôsobia ako modely fantastických krajín a miest, vždy v charakteristickej skratke a abstrahujúcej redukcii tvarov, kombinujúcej organické prírodné tvary s prísnou geometriou.

Väčšina z Gavulových prác pre zdravotníctvo sú dnes na okraji záujmu svojich vlastníkov. Fontány sú pre nedostatok technickej údržby bez vody, niektoré základné kamene zarastajú v zanedbaných areáloch zariadení, iné boli presunuté do interiéru, či len tak pohodené mimo pôvodného miesta, no aj vďaka trvácim materiálom stále existujú bez zásadných zmien. Zrkadlia tak stav nezáujmu, zanedbania a zotrvačnosti s ktorou v súčasnosti fungujeme.

Výstava upozorňuje nie len na potrebu starostlivosti o umelecké diela z čias socializmu, ale nabáda k väčšej citlivosti všeobecne v rovine záujmu o verejný priestor a spoločne prospešnú infraštruktúru.

Imprint

| Artist | Juraj Gavula, Matej Gavula |

| Exhibition | Homo Faber |

| Place / venue | Július Koller Society, Bratislava |

| Dates | 13 March – 30 May 2020 |

| Curated by | Daniel Grúň, Zlata Borůvková; cooperation: Peter Szalay |

| Photos | Leontína Berková |

| Index | Daniel Grúň Július Koller Society Juraj Gavula Matej Gavula Peter Szalay Zlata Borůvková |