‘Generations’ by Rachel Poignant at the Museum of Sculpture at Królikarnia

Retrospective—a most suited characterization. And it is not at variance with the term Premiere. It is the first, relatively complete, exhibition that shall encompass about 30 years of the artist’s work.

The explanation for this unwonted situation is simple: Rachel Poignant dedicated 30 years of her life to working with and on sculpture. She filled her time with work. All of her time. Leaving none for so-called promotion in the form of exhibitions, publications, etc. A case extremely rare.

Rachel Poignant was my student during the ‘80s/’90s at École Régionale des Beaux-Arts in Caen, France. A real artist in my opinion—working incessantly—she restored the original, true verb oriented meaning of the word work. In France, in the ‘60s/’70s, the term work of art (French travail) replaced the term masterpiece (d’œuvre d’art) for the sake of political arguments, as well as in protest of romantic vocabulary. It stumbled grammatically, becoming a noun, and stayed that way. In the language of contemporary artists, the word work has become contradictory. Now, its meaning only refers to causatum—i.e. a masterpiece.

But meanwhile, Rachel applied the word work literally, and filled her time with it. All her time.

The word labeur found its way into our conversation back in Caen; however, at that time, it perturbed and stirred her. The provocative introduction of this word into our first conversations appears today as the anticipation to Rachel’s current situation. But not only. It is about something more than just becoming part of a topicality. It is about giving in to destiny—about obediently accepting a life sentence. Rachel relinquishes her choice, choosing the necessity and accepting with full, almost painful awareness all the consequences of this decision. The consequences are surprisingly vast and terrifyingly radical. Is, therefore, obedience—a word rejected by a number of artists in the name of creative freedom—the key to this work?

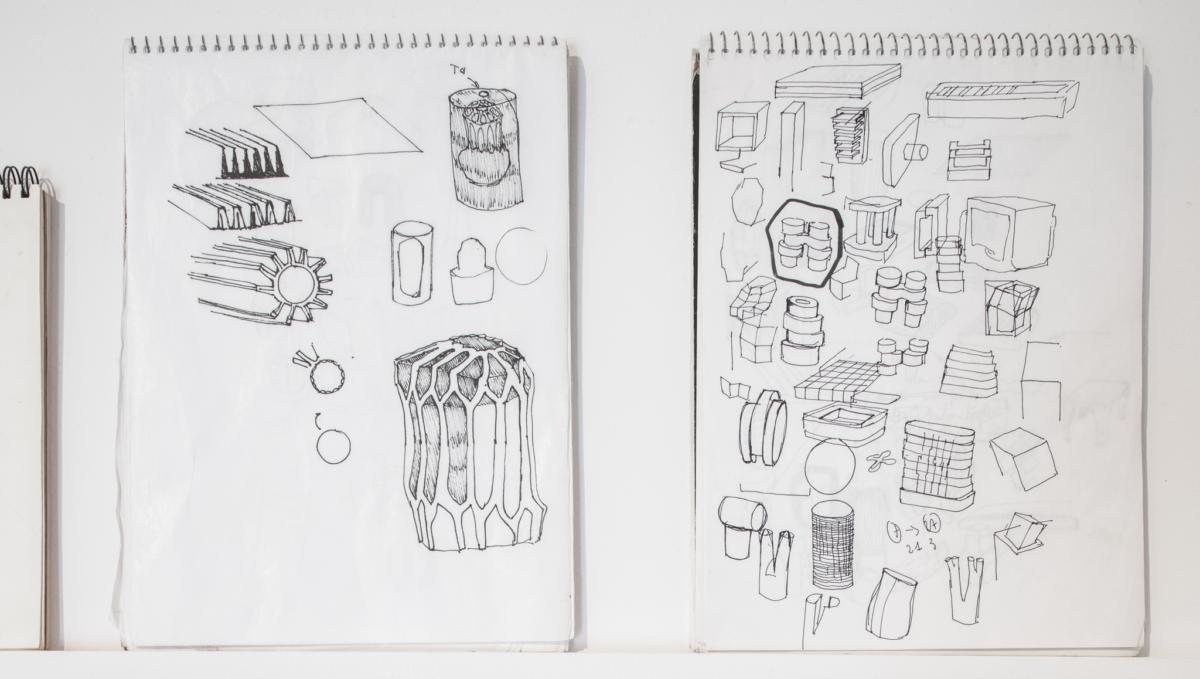

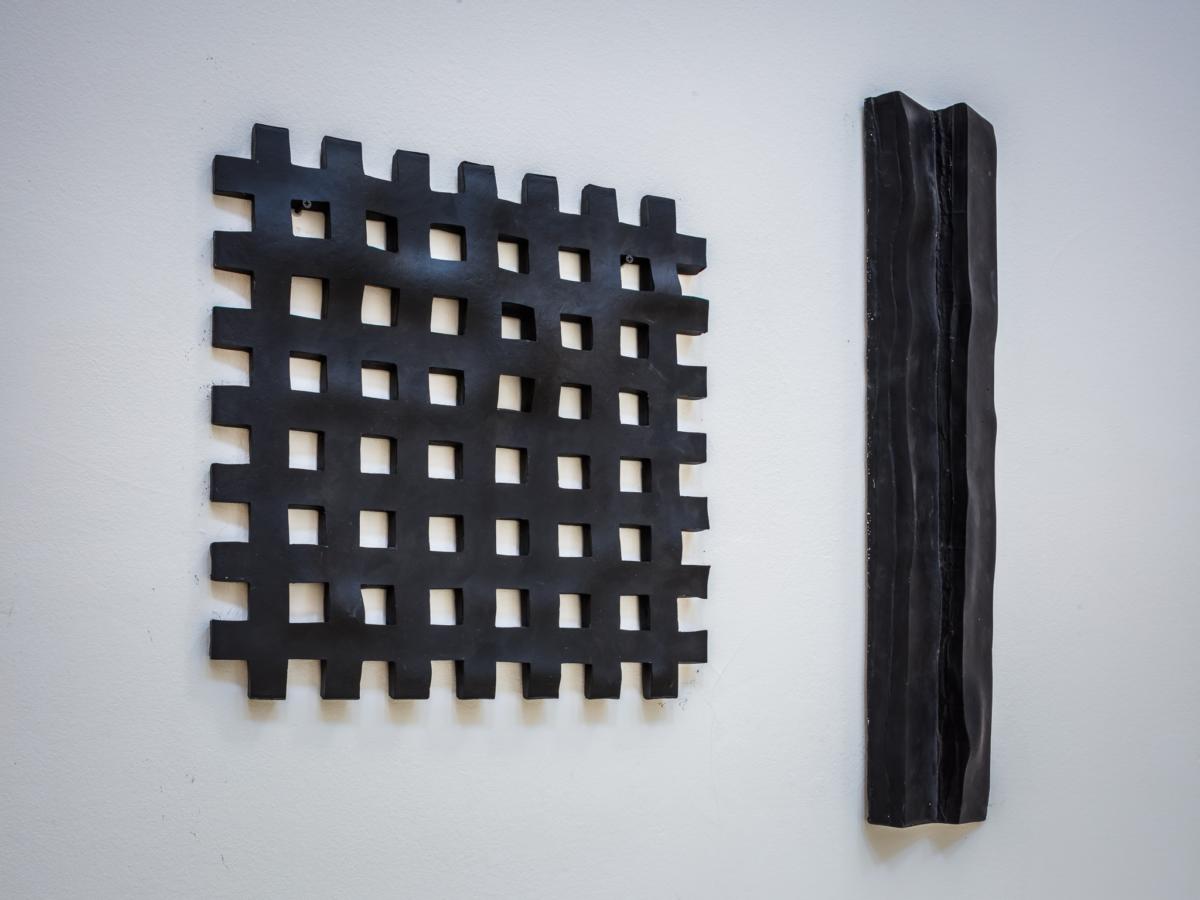

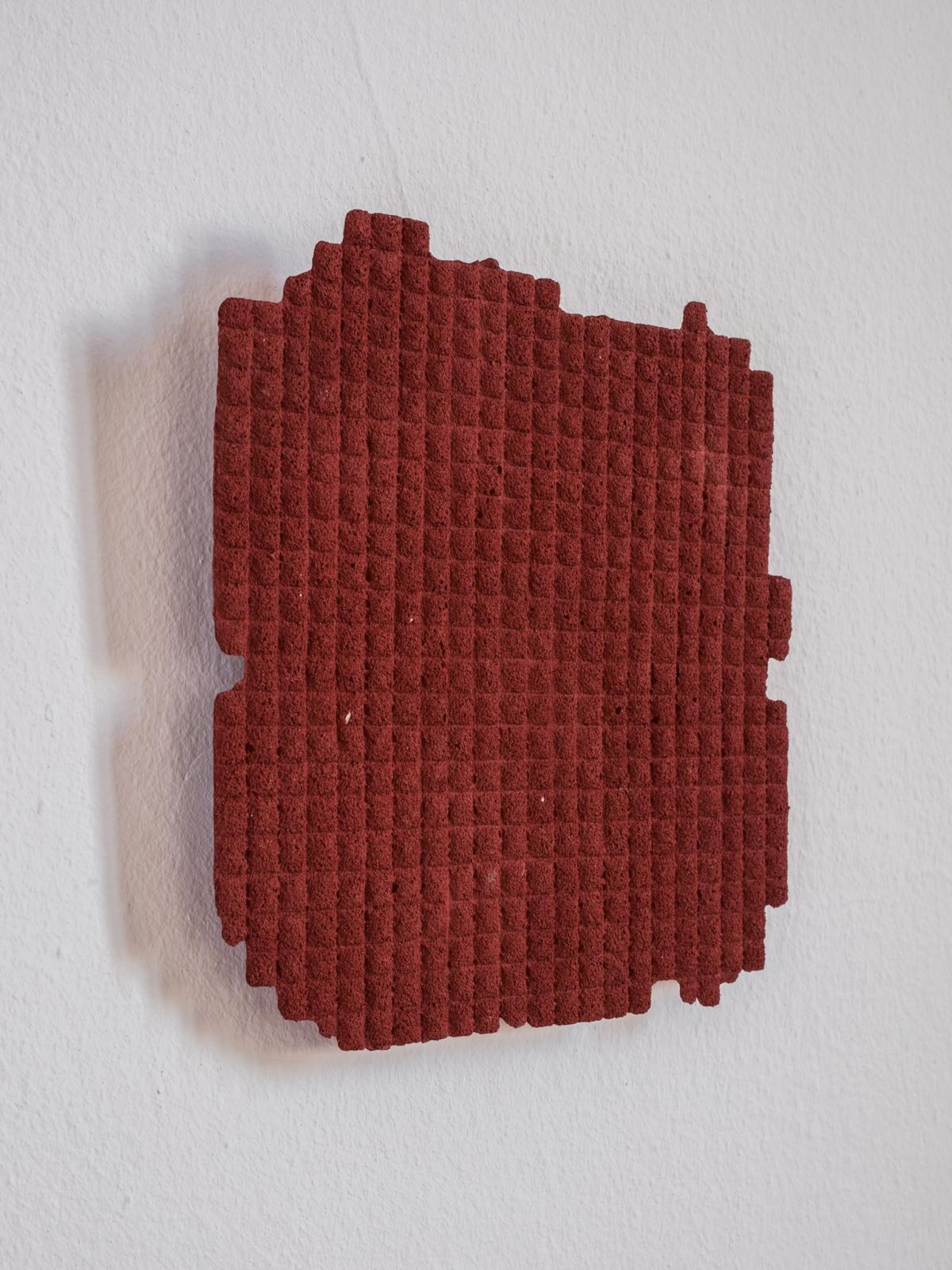

In any case, and in all probability, the appearance of these sculptures is not her goal. It is merely the result of the basic and complex processes that give rise to form. Each form, therefore, has its own—solely its own and easily readable—history of birth, in which there is no room for lies. Like life.

Hence why the term “formalism” is greatly misunderstood among Rachel’s sculptures. Contrary to appearances—it is not the artist who determines the external form. The work method she utilizes effectively eliminates so-called creative impulses. Instead, the clandestine laws of matter govern the beauty, subtlety, and the astounding as well as unabashed classicism of the form. The artist is able to discover them, listen to them, activate them, tirelessly watch over them, and never, under any circumstances, violate them.

In broadening the concept, but also the materiality of the work, we understand how comprehensive it is, which—visually—makes it imperceptible in its entirety, and therefore in what determines the status of a work. And it’s not about any kind of—avant-garde or not—protest. Rachel’s program is 100% positive. Each “insigni cant” piece, each fragment, is in itself a whole. But by remaining a fragment of the whole, it must incorporate the whole’s basic, decisive features—its minimum. Note that here, the “minimum” is suspiciously close to the “maximum.”

The word fragment refers us to the empirical sphere of activity, while the word whole—to its conceptual, theoretical definition.

This side of Rachel Poignant’s work can be seen as linguistic conditioning. By being subjected to constant empirical correction, the general definition of whole… creativity… art… is continuously modified, stubbornly remaining in proximity; being close means getting closer. It occurs while the work is creating its own space. Rachel is the guardian of this process—day and night.

From among the masses of fragments (I do not want to say objects, because in view of the word “object,” they retain the same wavering distance as with the word “whole”) Rachel took one o a nail and gave it to me. I hung it up above my bed on the wall, where I hang all the paintings dearest to me: her own, that of Henryk Stażewski, Edward Krasiński, and André du Colombier. Something strange happened: now a piece of Rachel’s studio is pulsating in my room as if it were alive, almost like an alien species. And what is stranger, but natural in its strangeness—is that it’s growing old with me: shrinking, graying, drying.

Rachel is certainly not the first artist to issue a war on her “artist’s situation,” imposed by the art distribution system. She describes it as, among other things, an incurable dissonance between the studio and the exhibition.

The rigor stemming from and imposed by the work—for Rachel—prompted the refusal of all forms of translocation. The refusal of circulation—the basis on which art functions. Denying functioning, which, therefore, can be characterized as artistic suicide if we accept the thesis (only appearing obvious) that art does not function outside of society.

A measure of the radicalism of this attitude are, paradoxically, the moments in which she steps away from it—their quality, motivation, discovery, and uniqueness. Among them, stubbornly but fluently, the artist is evolving, to which the exhibition at Królikarnia testifies.

The above aspect of Rachel Poignant’s work, about which her history tells convincingly, can be regarded as ethical conditioning. It does not express any external norm; it is nothing more than a surrender to the necessity that the work itself dictates. And necessity in art, however intimately it is known to some artists—has its own name. It appeared like a bolt from the blue, during a Parisian salon discussion about exhibitions, galleries, museums, and the price of artworks. “Imagine there is truth in art,” said André du Colombier, an artist who willingly condemned himself to the fringes, but who was also simultaneously condemned to remain there by others.

Since ethics have been mentioned, defined as above and which—let us say boldly—restore a place for art that was lost in postmodern retro-relativism and in the conditions of the capitalist market, then this is all the more reason to become extremely concerned with the particularities, avoiding a certain form of radicalism, which for a long time—an entire century—gave us authority in the world.

Anka Ptaszkowska

Imprint

| Artist | Rachel Poignant |

| Exhibition | Generations |

| Place / venue | Museum of Sculpture at Królikarnia, Warsaw |

| Dates | December 3, 2017 – February 18, 2018 |

| Curated by | Anka Ptaszkowska |

| Photos | Ernest Wińczyk |

| Website | www.krolikarnia.mnw.art.pl/en/ |

| Index | Anka Ptaszkowska Museum of Sculpture at Królikarnia Rachel Poignant |