Fragments from war-torn Ukraine

History and politics sometimes annex artworks, lending them meanings that artists would not necessarily wish for. Nowadays, this process can be seen, for instance, in the reception of artistic production from Ukraine. Regardless of the topics that Ukrainian artists address, their works are interpreted – also in Poland – in the context of the political turmoil of the recent years: Maidan, the fall of Yanukovych’s government, profound political polarization of the society, the rise of the extreme right-wing, the annexation of Crimea, hybrid warfare waged by Russia, separatist movement in the east of the country.

Working mainly with the medium of video, Mykola Ridnyi immerses himself in these issues and contexts. In his works, the artist defines contemporary Ukrainian politics in such a way so as to prevent it from defining his pieces. His productions consistently challenge the all-too-easy and intellectually sluggish schemes and oppositions (“pro-Russian East – European West”) that provide the prism through which the public opinion perceives the otherwise much more complex Ukrainian reality.

As seen from Kharkiv

What matters for the reception of Ridnyi’s works is the awareness of the vantage point from which he observes his country – the city of Kharkiv, the main urban and industrial centre of eastern Ukraine, the second largest Ukrainian city by population. It was in Kharkiv that the political conflict at the turn of 2014 took a particularly violent course.

The city became divided between the opponents and supporters of Maidan; each group occupied its own spot in the centrally located Freedom Square – one of the largest urban squares worldwide. Many of Yanukovych’s partisans hailed from Kharkiv. It was from this city that the administration of the infamously overthrown president recruited people to the “titushky” formations attacking Maidan in Kyiv.

After his fall, Yanukovych fled to Russia via Kharkiv. In the spring of 2014, a group of pro-Russian activists – seized the Kharkiv Regional State Administration and proclaimed the Kharkiv People’s Republic. Commentators were convinced that Kharkiv would soon share the fate of Luhansk and Donetsk and become yet another separatist centre of Novorossiya. Ukrainian special forces nevertheless managed to quickly re-establish control of the city. Pro-Ukrainian activists flooded the streets. Kharkiv remained loyal to Kyiv.

Although the streets of Kharkiv are relatively peaceful on an everyday basis, acts of terrorism happened there even as late as 2015, the year of a bomb attack targeted at patriotic pro-Ukrainian activists.

The afterimages of history

Ridnyi documents the most recent history of his city. At the same time, his approach to the documentary genre in art differs from that of Artur Żmijewski, Tomáš Rafa or Oleksiej Radynski, the latter active in Kyiv. Ridnyi’s works do not feature straightforward footage of violent historic events. The artist rather takes interest in what remains after them; in the way they last in the social memory and practice, long after the battle dust of events happening right in front of our eyes clears; in the after-images left underneath the eyelids when the current events slowly begin to go down in history.

The afterimages of the Kharkiv turmoil of 2014 are addressed directly in Regular Places , NO! NO! NO! and Blind Spot . All of them demonstrate the dialectical work of memory and oblivion, of remembering and forgetting, which occurs around the events that happened a few years ago in the artist’s city.

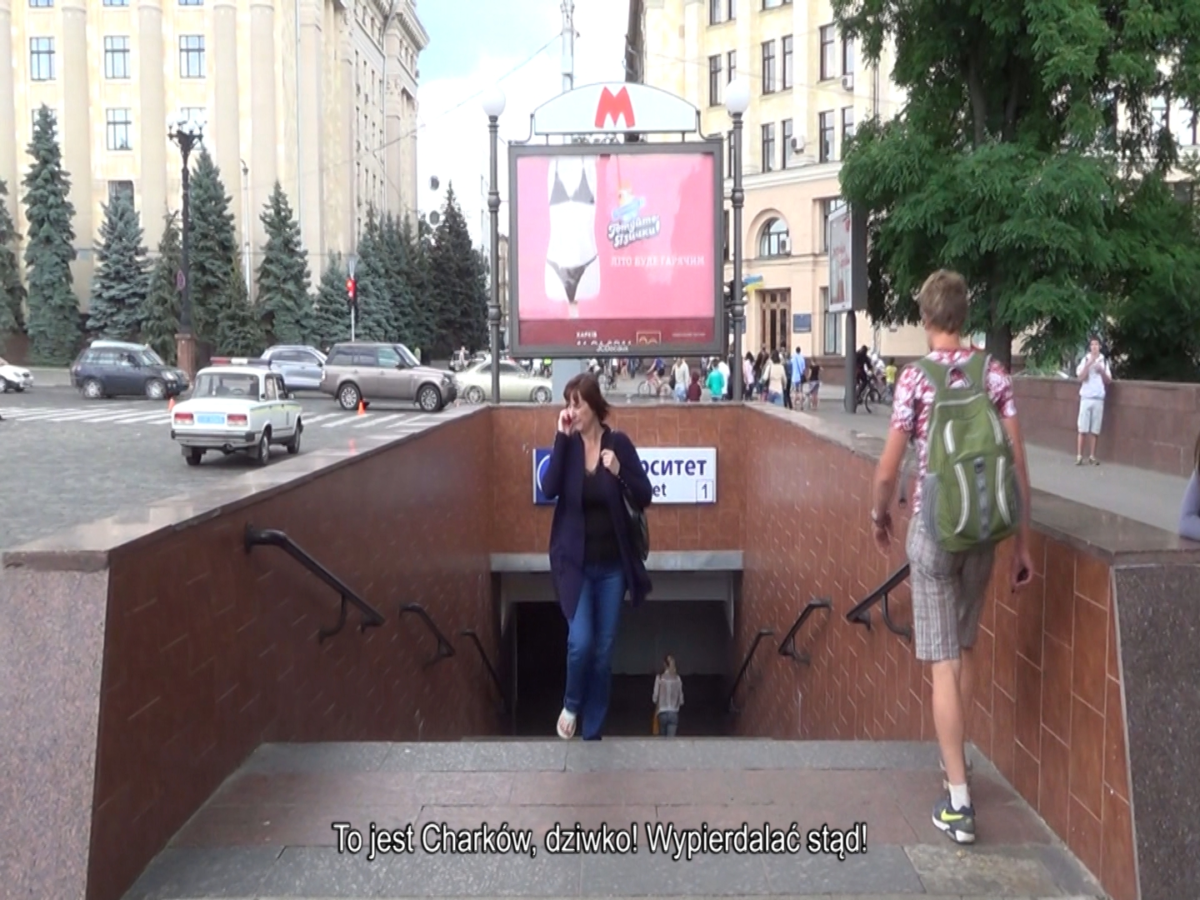

Regular Places , a piece from 2015, features a series of images of Kharkiv streets and squares, observed by a static camera on a tripod. The weather is warm, it is probably summertime, life is lived at an unhurried pace, urban spaces appear calm and depopulated. Nothing is essentially happening. Standing in stark contrast to this idleness, however, is the film’s soundtrack. We hear documentary recordings of the sounds of events that unfolded in the same places few months before: the noise of violent demonstrations, conflicts between ideologically polarized groups, clashes of radicals.

It is often difficult to grasp the sense of all the shouting and noise, and to determine who is demonstrating at a given moment and against whom or for what. Who fights with whom, and what they fight for. We hear shouts about “Novorossiya” and “Fascist Banderites’ from one side, and “Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the Heroes!” from the opposite side. We realise that not so long ago that idle landscape must have witnessed a violent conflict.

The most telling sign of this situation is an image of a facade of an ordinary block of flats (which appears to have been built right after the war) juxtaposed with a recording of a conversation between several people – perhaps dwellers of one of the flats whose windows can be seen. Judging from what they say, they are observing a clash between pro-Ukrainian football ultras and separatists. The dwellers initially seem to support the pro-Ukrainian group forces, they cheer them on to fight. Yet, the violence – although targeted against the political adversaries who serve Russia – becomes unbearable and terrifying. The recorded conversation acquires an increasingly anxious undertone.

How to interpret such contrasting montages of images and sounds? On the one hand, Ridnyi shows that afterimages, the social memory of the past violence and conflict, persist in the city’s (sub)consciousness long after everything seems to be back to normal. As in William Faulkner’s famous phrase about the American South, in Kharkiv as seen in Regular Places the past is not dead, it is not even past. On the other hand, we can see indeed that the city is resuming normal life and is capable of abandoning the state of conflict and creeping war at the basic level of everyday functioning. Despite the spectres of the brutal past, a difficult process of restoring normality begins – although the afterimages of violence will long continue to disturb it, haunting the present.

Regular Places is worth viewing alongside Ridnyi’s photographic work Blind Spot (2014–2015) – both pieces mutually complement one another by showing opposing, but at the same time complementary, processes. Blind Spot is a series of photographs borrowed from media coverage of the war in eastern Ukraine. Ridnyi destroys them using black paint – a large blot appears in the centre of each picture.

The artist situates this work in the context of information warfare against citizens of his country. The blots stand as symbols of distortions caused by aggressive war propaganda in our perception of what really happens in eastern Ukraine. But Blind Spot can also be interpreted in the context of memory and forgetting. Seen from such a perspective, a black stain becomes an allegory of war images fading into oblivion, which is a necessary process for the community to return to normal life after the war. The process of forgetting, however, always entails the risk of distorting the past and escaping the attempts to honestly settle accounts and rethink it.

Metaphorically present in Blind Spot , forgetting stands in contrast to the persistence of difficult memory that haunts Kharkiv in Regular Places . The two works are situated at the two extremes of contemporary Ukrainian memory – it is between these two extremes that the society needs to reunite after the conflict that has torn it apart.

Blows from the right flank

Ridnyi also demonstrates that the contemporary Ukrainian conflict is not limited exclusively to the division along the east- west line, to the dichotomy between those who support Maidan and the pro-Russian Party of Regions. The video NO!NO!NO! (2017) outlines a much more complicated map of divisions on the example of four young people from Kharkiv: a street artist, a model, a video game designer, and an LGBTQAI activist.

Each of them describes how the conflict between the pro- and anti-Maidan parties influenced their lives. The girl with a career in modelling recalls how people accosted her in the street and reacted aggressively because she had a ribbon in the colours of the Ukrainian flag attached to her clothes. The camera also follows a group of street artists working under the cover of the night. Walls in Kharkiv become an arena of struggles between different national and political identities. At the same time, what the street artists say to the camera complicates slightly the image of the conflict between the two Ukraines. They explain that the linguistic and political border often runs through the most intimate spheres and divides families, thus confronting individuals with complicated identity choices.

This image is rendered even more complicated by the first speaker in the video, who is non-binary and refuses to identify as female or male; a poet and an activist working for the non-heteronormative community. They talk about the sense of threat and acts of violence they have suffered from. Yet, such violence is not fuelled by the principal conflict that divides Ukraine and concerns the division between the east and the west, between speakers of Russian and Ukrainian, but it is rather stoked by homophobia and the ideology of the extreme populist right.

The latter becomes the topic of Ridnyi’s works united under the title It’s not a… (2018), which comprises two series of black and white photographs and a cycle of graphic prints. The first photography series – In Daylight – depicts close-ups of gestures performed by various right-wing politicians with their hands. We mostly see hands reaching out in a friendly way, resting on the hearts as if making an oath, and thumbs up, etc. All these images appear as if taken from a political marketing handbook, from guidelines for a smooth polished politician, who sells himself instead of seeking to convince voters to follow his political ideas – much in the same way as someone sells insurance or cars.

In the second series, Near Dark , images are deliberately blurred, unclear, faded. Shapes captured by the camera can be hardly discerned against the background. Nevertheless, a little effort suffices to recognise what happens in the photographs. They depict acts of violence, acts committed by partisans of the extreme right and populists – perhaps supporters of one of the politicians whose gestures feature in the previous series. Besides the blurred images of violence, the work also comprises a series of graphic prints titled Facing the Wall – symbols of various extreme right-wing organisations covered with a sticky chewing gum. We can discern the hand with a sword in the emblem of Polish Falanga. We would probably fail to recognise many other symbols even if they were shown in their entirety. The symbols originate from all across Europe.

It’s not a… shows the processes of whitewashing and normalisation of the extreme right-wing ideology that takes place in contemporary democracies. Such processes occur not only in places like Hungary, Slovakia or France but also in Poland, where the public presence of such forces as the National Radical Camp (ONR) has significantly intensified – tolerated, to say the least, by the state authorities – during the last three years. The juxtaposition of these three series of images draws our attention to an intimate link between two key problems of contemporary democratic politics. On the one hand, there is post-politics – smooth, devoid of content and dictated by marketing whizzes; on the other hand – extreme right-wing populism often with a Fascist flavour.

In Ridnyi’s vision, both these phenomena appear as the obverse and the reverse of the same coin, as two symptoms of the same crisis of political representation in a democratic system. As the problems that can only be solved jointly.

Alternative genealogies

Where to look for solutions to a crisis that manifests itself in such a two-fold way? Ridnyi does not pretend that he can answer this question. Yet, at the same time, he attempts to seek political genealogies for contemporary Ukraine beyond the nationalist tradition. In the video Grey Horses (2016), the Kharkiv artist reminds Ukrainians of their anarchist traditions connected with Nestor Machno. Active a century ago, that anarchist leader strove to establish a community founded on anarchist principles in the southern Ukrainian region around Huliaipole. His troops fought with everybody: the Red Army, the White movement, forces of Ukrainian People’s Republic and various lesser atamans. It therefore comes as no surprise that Machno’s movement suffered a double defeat: both military and with regard to building a new society on territories under his – short-lived and unconsolidated – control.

Ridnyi introduces the history of Ukrainian anarchism through the prism of his own great-grandfather Ivan Krupskyi, who fought in Machno’s anarchist troops and headed his own squad. Akin to the work Regular Places , where history becomes intertwined with the contemporary era, in this piece the artist’s grandfather’s memories are superimposed as text on the image of modern-day Ukraine – video footage from places where Krupskyi resided and acted one hundred years before. Those memories are performed for the camera by contemporary Ukrainians from various social groups, from contemporary anarchist activists to – ironically enough, given the biography in question – members of police forces. The protagonists of the video not only embody the anarchist from a century ago but also speak in front of the camera about contemporary Ukraine and their own problems.

Nevertheless, in Grey Horses , Ridnyi does not seek to build a myth, either around his grandfather’s figure or around the tradition of Ukrainian anarchism. We are told, for example, that Krupskyi most probably first had raped the woman whom he later married. His life amongst rebel group was far from idyllic. He was deemed a traitor and banished from the squad. He later returned, but his conflicts with some companions were never resolved. In Ridnyi’s video, anarchism from one hundred years ago becomes a movement characterised by an extremely toxic political culture mired in ongoing suicidal, cannibalistic sectarian struggles. A similar image of contemporary anarchism actually emanates from comments by activists from a certain squat, who speak for the artist’s camera.

Even if both anarchism from a century ago and nowadays anarchism appear in Grey Horses rather as dead-ends, the sheer fact of making these traditions visible in the field of art opens up Ukrainian political imagination and transforms the frame of discussion about the contemporary political identity of the divided country.

That’s what we wanted!

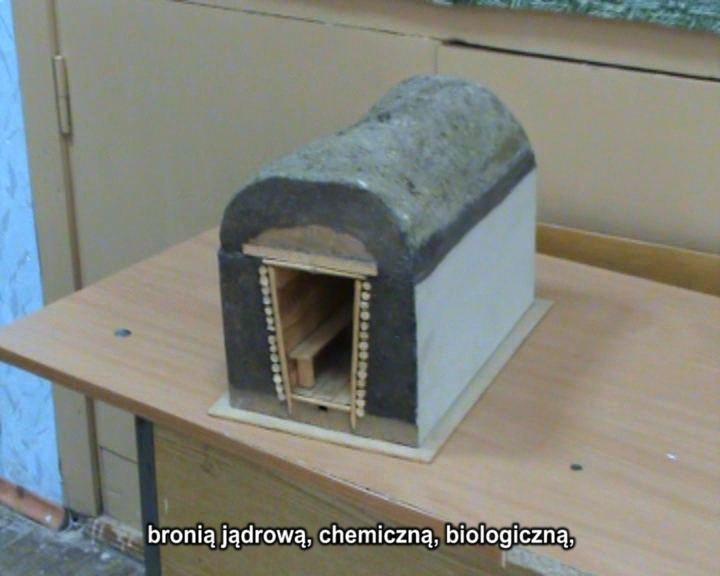

Ridnyi’s artistic production begins prior to Maidan, but it is the post-Maidan contexts that determine the prism through which we view even the artist’s earlier works. Let us take a look at the video Shelter from 2013, set in an underground bunker where Ukrainian students have received pre-service training since the Soviet times. An elderly teacher speaks for the camera. He presents old training boards, models of grenades, ammunition and other tools of destruction. We can see him training young people in shotgun disassembly and reassembly in the shortest possible time.

We perceive these images in the context of today’s war in Ukraine and the accompanying militarization of civic consciousness. Yet, we soon realise that the film was shot prior to the war in the east of the country, while the entire military-paranoid imagination symbolised by the bunker, the language used by the teacher and the gathered educational props originate from the Soviet era. The roots of violence experienced by Ukraine today may be more profound that it would appear in television news that reaches Western audiences.

However, the context of the war waged in the east of Ukraine may invite yet another interpretation of Shelter . It may compel some viewers to review their pacifistic, anti-militaristic attitudes with which they probably approach the work. Bearing in mind the resolute action by Ukrainian forces that spared Kharkiv the fate suffered by Donetsk, it is impossible to avoid the question: is pacifism always an attitude that works? Even if we answer in the negative, it is still difficult to come to terms with the artefacts of militaristic imagination amassed in the eponymous shelter.

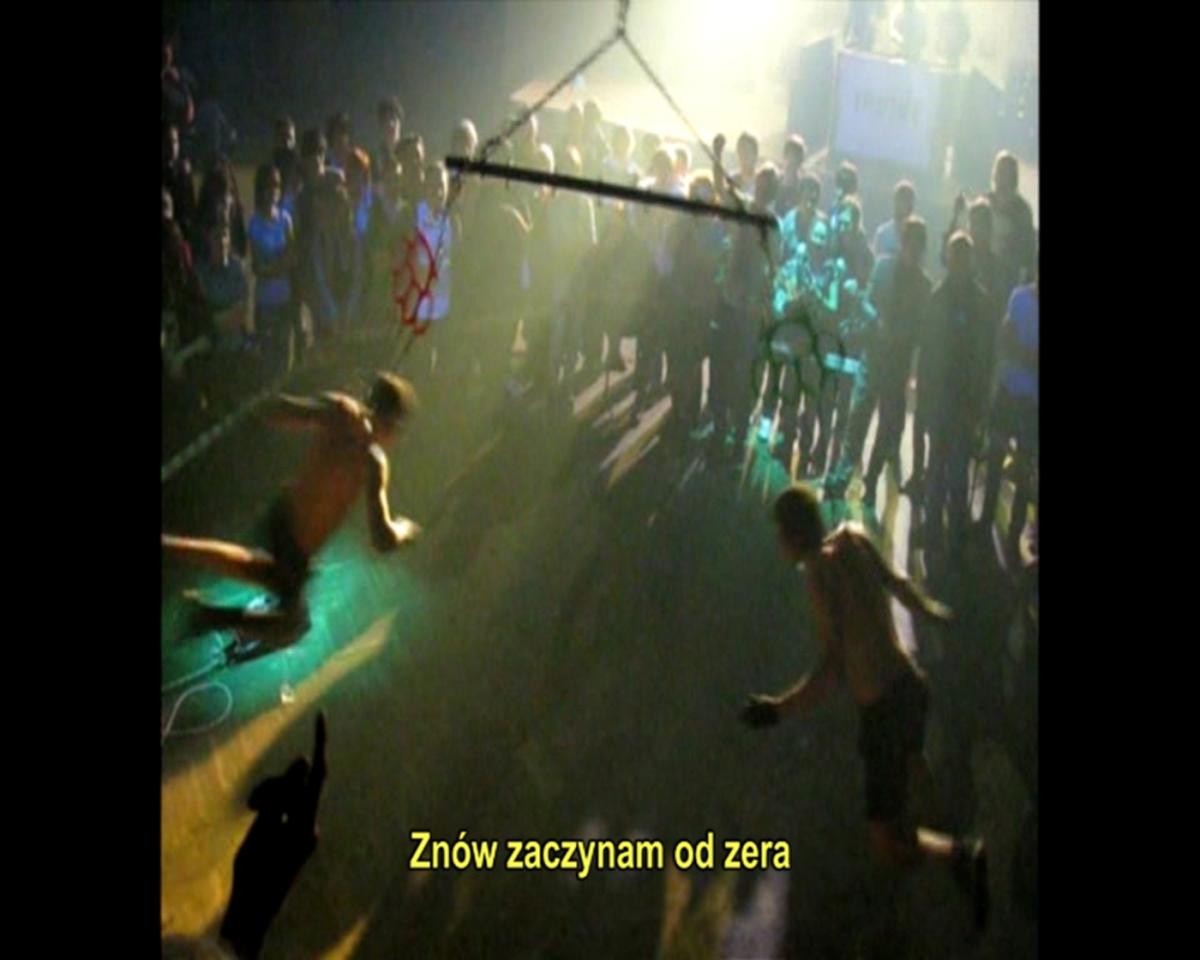

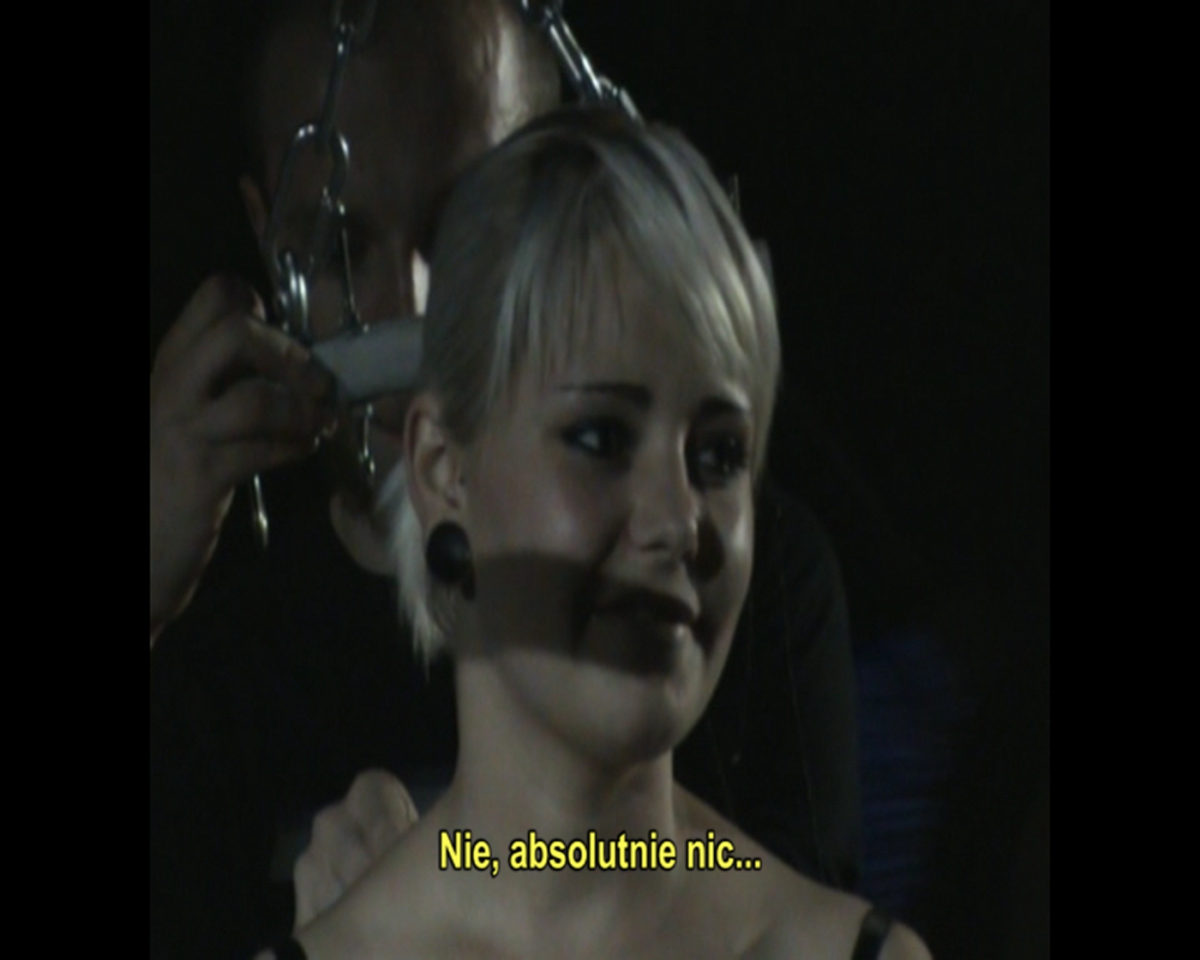

The most recent history also determines the reception of even those works by Ridnyi that are seemingly remote from politics, such as No Regrets (2011 / 2016). The video features footage from a night club where young people pierce and suspend their bodies, thus seeking extreme physical experience. Curved hooks pierce the legs of a young man near his knees as he hangs with the entire weight of his body, head downwards, suspended on a moving structure that rocks faster and faster. The video confronts us with several such shots accompanied by the soundtrack of a broken record with Edith Piaf’s songNon, je ne regrette rien. English translation of the lyrics appears on the screen: “No, I regret nothing.”

How to understand such a combination of image, sound and words nowadays? As an involuntarily gruesome metaphor of the fate of the generation that sought extreme experiences only to eventually find them at war? Such an interpretation is justified by the fact that Piaf’s song later became an unofficial anthem of the French Foreign Legion. Perhaps one of the young people seen in No Regrets would later join the ranks of numerous volunteer battalions fighting for Ukraine?

The video also offers a declaration of a subjectivity that is not founded on resentment – uncontaminated with regrets about one’s own past and choices. Looking at the video recording of their acts, the protagonists of No Regrets would probably say: “That’s what we wanted”. The words “that’s what I wanted” uttered by an individual or a community, such as nation, are a sine qua non condition of maturity, a gesture with which every subjectification begins. Engaged in internal disputes about its own past, identity and future paths, Ukraine desperately needs such a mature subjectivity without a foundation in resentment. For it is only by abandoning regrets about the past that one can come to terms with it.

In the context of the discussion about national identity, the video from the club for fetishists of extreme bodily sensations comes across as a rather eccentric source of inspiration, yet the power of artistic production consists in the very fact that it may offer inspiration in unobvious ways.

Text: Jakub Majmurek

Imprint

| Artist | Mykola Ridnyi |

| Exhibition | Facing the Wall |

| Place / venue | Galeria Labirynt, Lublin |

| Dates | April 20 - June 15, 2018 |

| Website | labirynt.com/en |

| Index | Galeria Labirynt Jakub Majmurek Mykola Ridnyi |