One hundred years after the peak of modernism, our imagination about the future has shifted form. The genre of science fiction has flattened, the future and past collide and act as a speculative criticism of present conditions. This exhibition stems from the material and utopian thought that collide in unresolvable conflict at the moment of practice. Process moulds form, objects become dust and become the tabula rasa from which future ideas emerge. The problems which face us today including rising inequalities, the toxicity of the earth, exclusion of the body, and labour precarity among others, are topics which have been endlessly addressed by the science fiction genre. The exhibition raises these issues through speculative critique or specific processes pointing to a non-human agency and the cyborg body.

Although science fiction exists in the realm of the imagination, its concerns often have to do with material conditions. The following passage of Ursula Le Guinn’s The Dispossessed compares material conditions of objects between the imaginary expanded geography of cold war politics. An allusion to the cold war state of relations between the United States and the Soviet Union, the plot follows renowned scientist Shevek from anarcho-communist controlled Urras through a scientific mission to its accelerated capitalist “propertarian” twin Anarres.

“When first aboard the ship, in those long hours of fever and despair, he had been distracted, sometimes pleased and sometimes irritated, by a grossly simple sensation: the softness of the bed. Though only a bunk, its mattress gave under his weight with caressing suppleness. It yielded to him, yielded so insistently that he was, still, always conscious of it while falling asleep. Both the pleasure and the irritation it produced in him were decidedly erotic. There was also the hot-air-nozzle-towel device: the same kind of effect. A tickling. Moreover, the design of the furniture in the officers’ lounge, the smooth plastic curves into which stubborn wood and steel had been forced, the smoothness and delicacy of surfaces and textures: were these not also faintly, pervasively erotic?

Ideological approaches to material comfort surrounding the body in which cell phones and other internet-connected devices are increasingly fitted to designs of the body appear in common marketing techniques from Apple to Android and Google Glass. That this coalescence of the biological body and new technologies has appeared under capitalism indicates that notions of economy and individuality are core to these developments as well as increasing inequalities between developed and developing nations in terms of biopolitics.

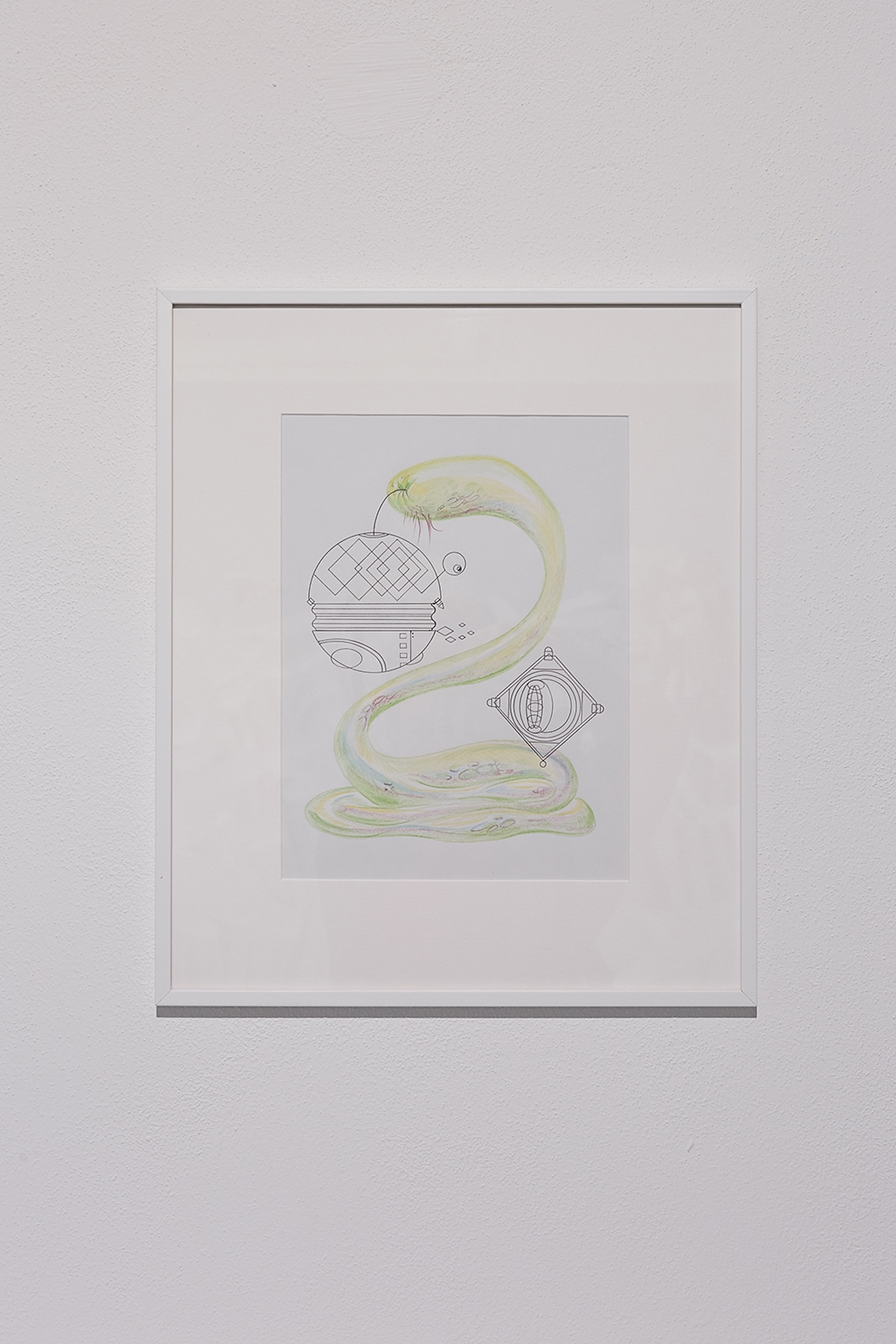

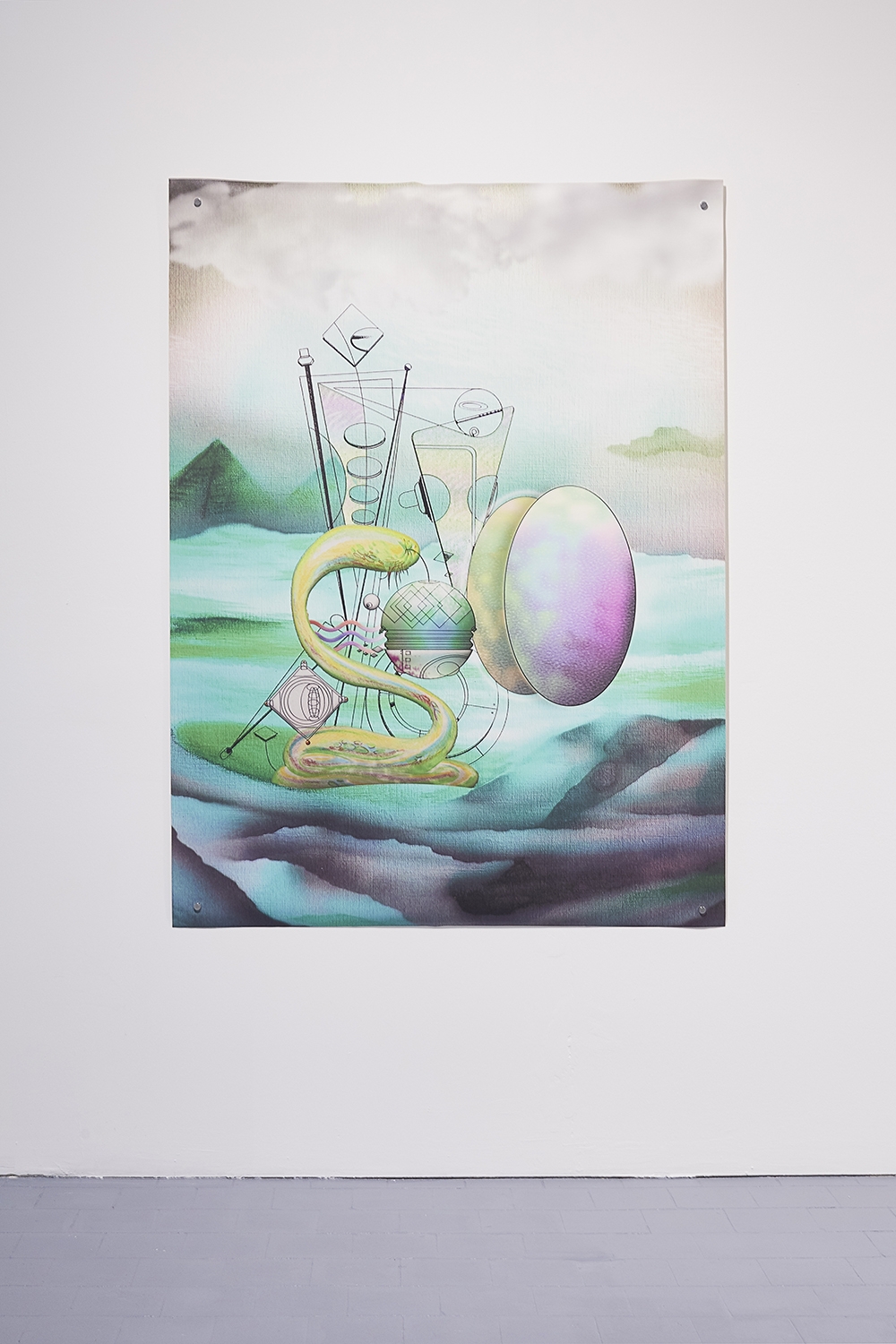

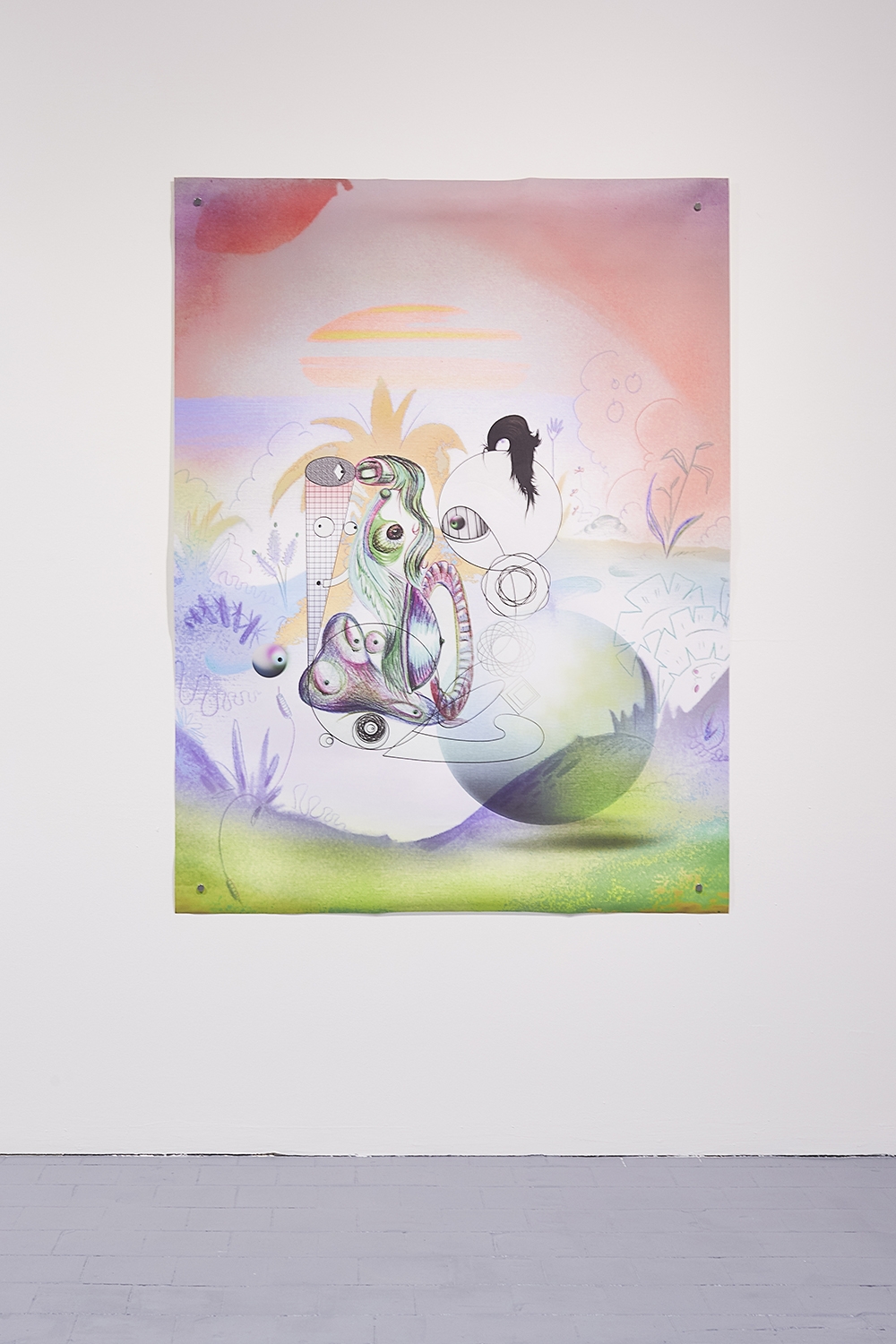

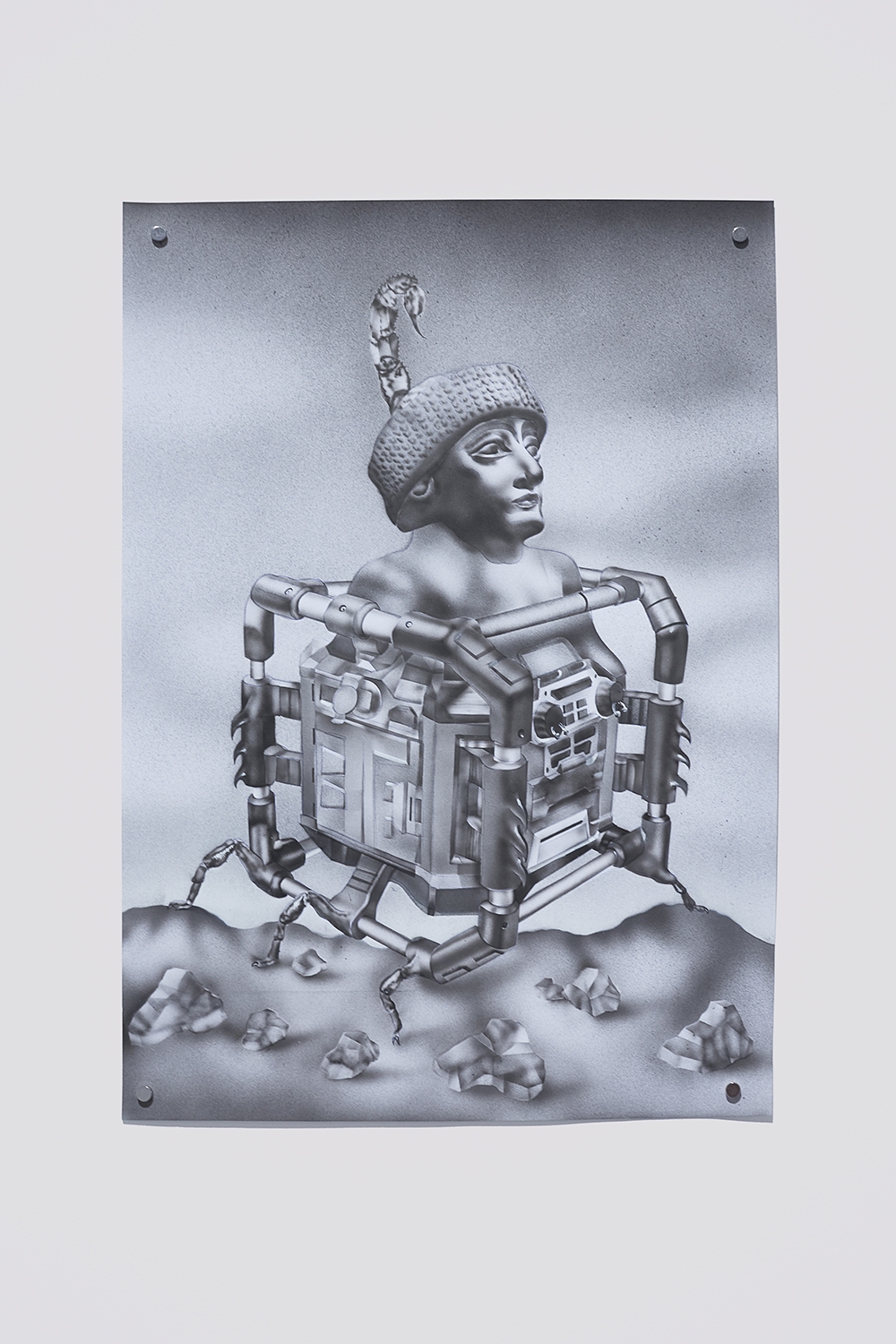

Technology is already redefining the human body and our relationship to nature. This exhibition compares the pictorial space of the imaginary with the sculptural conditions of material reality. While imagination can expand into worlds free of gravitation and time, sculptural materiality gives way to a non-human agency. Considerations of bodies and limits appear in Evita Vasiljeva’s concrete, and PVC humanoid forms are emitting hormonal variations or gentle breathing gestures. Ad Minoliti’s abstract bodies replay modernism in an age of bodily re-definition where gender vanishes and is replaced by cyborg geometric sensualities. Cyborg bodies are brought up in Julia Varela’s Mehr Fantasie in which plasma-screen powder is used as a sinister skin treatment masque, one replete with toxic consequences and the eath-smothering geological layer of the Anthropocene. Varela’s powder next to Vasiljeva’s breathing sculptures transmits the choking hazard of post-human toxic earth. In a mystic turn, Botond Keresztesi’s collaged elements see a world of insect warriors in abstract spatial planes – a universe parallel to ours made of references to digital space and modernism.

Modernism features in the compositional gestures of Minoliti and Keresztesi. The legacy of Suprematism and geometric abstraction lives on in contemporary depictions of space. Digital software programmes have made this space real – a blank canvas to fill with our dreams. Both artists remix the traditional narrative into new formations and code. The concrete of Vasiljeva’s structures echo the lost dreams of Bauhaus architecture and the ruins of a utopia that never came to be. Varela’s powder corpse of plasma-screen vision lies on the ground like a pulverised black square. One hundred years on from Malevich and Le Corbusier, our material conditions have yet to be overcome. Do not let the dream die – this is a bid to keep exploring other worlds.

As technology and bodies come together in the speculative design, notions of gender and identity surface. The way that technology develops originates from the societies we inhabit and inherits its customs, flaws, and preconditions. Like the generational cyborg devices developed by Lynn Hershman Leeson including the 1974 project Roberta Breitmore performs like a real person while being an avatar and performed identity. The self-surveillance and self-recording of this project contrast with the real-life invasive surveillance described by Trevor Paglen which reproduces existing structures of power related to gender, race, and income.

While this article discusses racial profiling enforced by algorithmic machines, gender identity emerges at the core of robotics itself. With service-related AI such as Siri or Amazon’s Alexa maintaining the science-fiction trope of robotic female bodies, Bob Bicknell-Knight highlights the power imbalance of this societal construction. “We now have Amazon’s Alexa, reinforcing the view that women are inherently subservient,” and points to the idea that future generations of AI might question the genders attributed to them.

Looking into the future as a form of criticism of the contemporary is a tradition that reaches us from the history of literature. Although the term “science fiction” did not emerge until the 1950’s, its form is found as far back as the magical folktales and other speculative fiction such as Margaret Cavendish’s 1666 “The Blazing World” and Mary Shelley’s 1818 “Frankenstein.” Parallel to the modernist practices marking 100 years in time, Karel Čapek’s RUR coined the term “robot” and is still universally in use. The origin of this word relates directly to the script of Čapek’s play and the old Slavic root Rabota, meaning forced labour or servitude, and speaks of questions of labour, feminism, and technology that show the continuous struggles of our generation and one century before.

“Robots of the world! The power of man has fallen! A new world has arisen: the Rule of the Robots! March!”

Written shortly after the Bolshevik revolution in the context of the new Czechoslovak state, Čapek encountered the pre-war period of industrial wealth conglomerations, labour exploitation, changing moral codes and gender roles, and the rise of ethnic nationalism. While the robots who themselves slowly gain consciousness represent the awakening and manipulation of the working class, the novel itself centres on characters that represent the state and corporate interests. Young Helena is the daughter of the president, who is forced to marry one of RUR’s CEOs. Her position as the only female character in the play attributes the essentialist values of caregiver and activist and posits her desire for good in the world against the logical rationality of the greedy shareholders.

“DOMIN:

What sort of worker do you think is the best from a practical point of view?

HELENA

: Perhaps the one who is most honest and hardworking.

DOMIN

: No the one that is the cheapest. The one whose requirements are the smallest. Young Rossum invented a worker with a minimum amount of requirements. He had to simplify him. He rejected everything that did not contribute directly to the progress of work – everything that makes the man more expensive. In fact, he rejected the man and made the Robot. My dear Miss Glory, the Robots are not people. Mechanically they are more perfect than we are, they have enormously developed intelligence, but they have no soul.”

The literary creation of robots alludes to the growing inequalities of our time, but also to the fear of losing control, the ascent of singularity, and the state of the precarious worker whose rights, freedoms, and liberties are besieged continuously by those desiring greater profit from products of labour. The mechanical bodies of the robots who only find love once they overthrow their masters give materiality to the labour force. If written in the age of cyborgs, the robots of Čapek might have been a more explicit allusion to AI – an external force which aspires to the status of humanity and supersedes it rather than a mechanically-advanced organism.

With the persistence of demands from unvoiced majorities and an accelerating circularity of trends ending in the total collapse time itself – extra-planetary commitment positions itself in speculative critique from outside of repressive forces. Only through the creation of a tabula rasa can we imagine utopian scenarios that create the case for building a shared future. This process calls for the de-legitimisation of institutions and towards concrete constructions for our times. In Celeste Olalquiaga’s 1992 Megalopolis, nostalgia for better times when the future was possible shows the overarching narrative that continues to this day. She states that “together with an escalating production of commodities and an emphasis on the nuclear family, post-war scientific development sought to achieve absolute control over the matter by making of outer space the displaced vehicle through which to imagine material security.” Yet, in a vastly more physically insecure place compared to earth, all it reveals is our current fragility in the face of natural forces and desire to escape our self-made future. By giving voice to material and reversing the instituted echelons of hierarchy, we can begin to create an alternative imaginary.

Imprint

| Artist | Botond Keresztesi, Ad Minoliti, Julia Varela, Evita Vasiljeva |

| Exhibition | Extra-Planetary Commitment |

| Place / venue | lítost, Prague |

| Dates | 16 March – 28 April 2019 |

| Curated by | Àngels Miralda |

| Website | litost.gallery |

| Index | Ad Minoliti Àngels Miralda Botond Keresztesi Evita Vasiljeva Julia Varela lítost |