![[EN/PL] ‘Territory’ at Wrocław Contemporary Museum](https://blokmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/08-1200x800.jpg)

[EN]

A territory can be understood as an imprint on the surface of the earth, an area whose boundaries are clearly delimited due to some specific properties. Defined in this way, a territory bears traces of human activity – in the form of setting boundaries, naming, marking or controlling. The Latin root terra means land, which is crucial to both biological and political territories. The exhibition consists of two artists’ works referring to the subject of animal and human territories – their interdependencies, permeability, boundaries between them, as well as who marks them, according to what rules and measures. For Netta Laufer, the area of Palestine and Israel became a lens focusing these phenomena, while Tom Swoboda analysed a zoological garden.

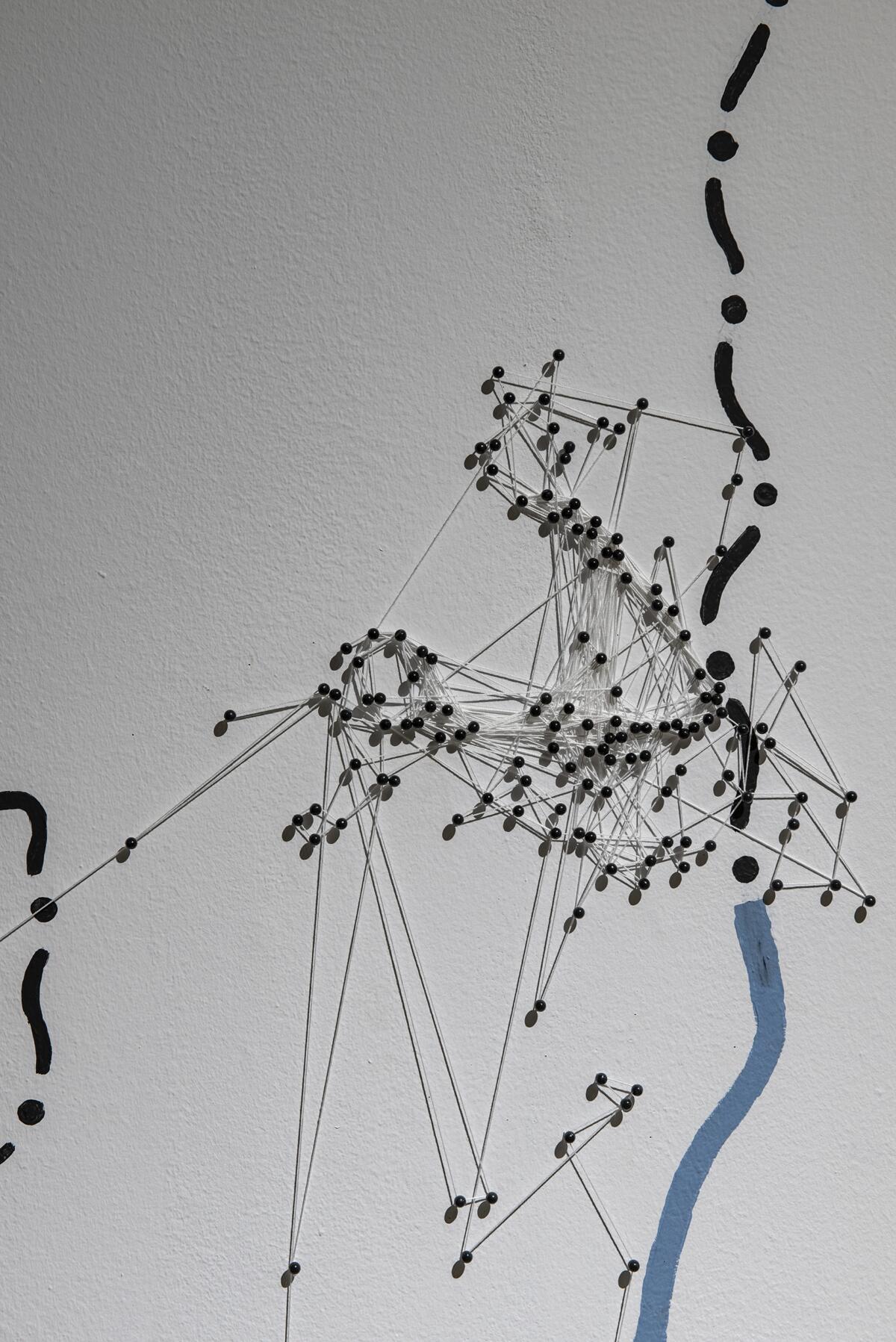

Laufer’s works are based on materials from CCTV cameras and motion tracking cameras as well as maps and technical drawings, so the artist assumes the position of an external and distanced observer whose perception is additionally mediated by recording devices. The eye becomes a tool for research, tracking and control. The works highlight important aspects associated with looking: the desire for power, the tendency to capture and hold, to objectify and perceive holistically. The observed animals and their territories are reduced to abstract spots, lines and dots, which makes surveillance easy. Here, biological and political territories simultaneously overlap and clash with each other. The natural instincts of the animals trapped in this conflict are out of balance, which mirrors human divisions and feuds. By appropriating data from devices used in the surveillance of conflict zones and transferring the footage to the new situation, the artist accentuates those aspects of the technology that are not useful in the original context. In this way, she offers a poignant commentary on the long-lasting conflict in the present-day territory of Israel.

Swoboda, on the other hand, explores the artificial world of zoos. However, he abandons the role of a viewer following the paths imposed by the eye-centric architecture of such places. The artist mixes the human and animal order by changing perspectives – he places himself in a cage, focuses on seemingly insignificant details or confuses perception. In principle, devices used to capture images from the animal world are intentionally masked, invisible, so that the viewer has the impression of penetrating the new world. But Swoboda’s photographs are different – the camera does not reveal anything, it actually emphasises the impossibility of seeing. Due to the multitude of details and reflections, the image is often unclear, blurred, which does not bring the viewer closer to animals. To paraphrase John Berger, the more we look at them, the farther they are, especially since animals are almost absent in Swoboda’s works. They remain on the fringes of the illusory, theatre-like environment of the zoo. Perhaps, as Berger claimed, the margins are more real than a steppe painted on the wall or the tropical plants – puny imitations of the territory they have lost. The spaces photographed by Swoboda are multilayered, as if the successive elements were supposed to somehow make them more refined. Improving the infrastructure of zoos in line with new research and architectural trends is nothing but a futile attempt to repair and expand a structure that cannot be repaired. A similar purpose is fulfilled by the passageways in the wall in the West Bank in Laufer’s work entitled 35 cm, which were intended to enable the animals to move within their territories, but instead have altered their behaviour even more.

The venue strongly determines the way both artists’ works are perceived. The concrete, claustrophobic interior of the former German air-raid shelter meets with the border wall that brutally cuts through the landscape and divides the territory in Laufer’s works. Concrete is also a material that has been commonly used in zoos. According to the visions of modernist architects who ignored the real needs of animals, it was supposed to trigger associations with modernity and make the observation of animal species more dramatic, as if they were watched in a cinema. The architecture of the shelter, characterised by multiple rings, determines circular movement inside it, resembling the movement of an animal in an enclosure with a strictly defined territory. The boundaries can be tangible or invisible, but they act with the same power.

[PL]

Terytorium można rozumieć jako odcisk na powierzchni ziemi, obszar posiadający jasne granice, wyznaczone ze względu na jakieś właściwe dla niego cechy. Tak definiowane terytorium nosi na sobie ślady ludzkiej działalności – w wytyczaniu granic, nazywaniu, znakowaniu czy opanowaniu. Z kolei łacińskie słowo terra wyraźnie wybrzmiewające w „terytorium” oznacza ziemię, bardzo istotną zarówno dla biologicznych, jaki i politycznych terytoriów. Na wystawę składają się prace dwójki artystów odnoszące się do złożonych zależności zwierzęcych i ludzkich terytoriów, ich przenikalności oraz istniejących między nimi granic, a także tego, kto, według jakich zasad i środków, je ustala. Soczewką pozwalającą dostrzec wspomniane zjawiska stał się dla Netty Laufer teren Palestyny i Izraela, natomiast dla Toma Swobody ogród zoologiczny.

Laufer w swoich pracach bazuje na materiałach z kamer przemysłowych, kamer śledzących ruch, mapach, rysunkach technicznych, przyjmuje zatem pozycję zewnętrznej i zdystansowanej obserwatorki, której percepcja zapośredniczona jest dodatkowo przez urządzenia rejestrujące. W jej pracach oko jest narzędziem badania, śledzenia i kontroli. Ujawnia się w nich wola władzy, jaką ma wzrok i jego silna tendencja do chwytania i zatrzymywania, do urzeczowiania i ujmowania w całość. Zwierzęta i ich terytoria sprowadzane są do abstrakcyjnych plam, linii i punktów, co ułatwia ich nadzór. Terytoria biologiczne i polityczne przenikają się tutaj i konfrontują. Uwikłane w te starcia zwierzęta doznają zachwiania życiowych funkcji, ale też zaczynają pełnić rolę zwierciadeł ludzkich podziałów i waśni. Artystka odzyskuje dane z urządzeń służących do kontroli stref konfliktu i przenosi je do nowego porządku. Akcentuje ich nieprzydatne w pierwotnym kontekście aspekty, dzięki czemu mogą stać się one przejmującym komentarzem wieloletniego sporu toczącego się na terenie obecnego Izraela.

Swoboda natomiast eksploruje sztuczny świat ogrodów zoologicznych, uwalniając się jednocześnie z roli widza podążającego ścieżkami narzucanymi przez okulocentryczną architekturą takich miejsc. Artysta miesza ludzki i zwierzęcy porządek poprzez zmiany perspektyw, umieszczanie samego siebie w klatce, poprzez skupianie się na pozornie nieistotnych detalach czy zaburzanie percepcji. Stosowanie technologii w rejestrowaniu świata zwierząt ma w założeniu sprawić, że urządzenie zapisujące będzie nieobecne, niewidoczne, a ujęcia stworzone tak, by dawały wrażenie wnikania. Tymczasem w fotografiach Swobody jest inaczej – aparat fotograficzny niczego tutaj nie odkrywa, a wręcz uwypukla niemożliwość zobaczenia. Obraz jest często nieklarowny przez wielość detali, refleksy, odbicia i nie sprawia, że jesteśmy bliżej zwierząt. Parafrazując słowa Johna Bergera: im więcej na nie patrzymy, tym są nam one dalsze. Zwłaszcza, że w pracach Swobody zwierzęta są prawie nieobecne. W iluzorycznym środowisku ogrodów zoologicznych, w ich teatralnych stenografiach przebywają na obrzeżach, bo może (jak chce Berger) jest tam coś prawdziwszego niż wymalowany na ścianie step czy tropikalna roślinność – nędzne protezy utraconego przez nie terytorium. Przestrzenie fotografowane przez Swobodę są wielowarstwowe, jakby kolejne ich elementy miały ją w pokraczny sposób udoskonalić. Polepszanie infrastruktury ogrodów zoologicznych zgodnie z nowymi badaniami i architektonicznymi trendami jest ciągłym jej nieudolnym naprawianiem i nadbudowywanie struktury, której naprawić się nie da. Podobny cel prześwieca tunelom w murze z pracy „35 cm” Laufer, który ma przywrócić zwierzętom część ich terytorium, a zamiast tego ingeruje jeszcze głębiej w ich zachowania.

Miejsce silnie determinuje sposób odbioru prac obojga artystów. Betonowe, klaustrofobiczne przestrzenie poniemieckiego bunkra łączą się z brutalnie wpisanym w krajobraz murem dzielącym terytorium, o którym mówią prace Laufer. Beton to też materiał powszechnie stosowany w ogrodach zoologicznych, gdzie, zgodnie z wizjami modernistycznych architektów ignorującymi prawdziwe potrzeby zwierząt, miał kojarzyć się z nowoczesnością i podnosić dramaturgię widoku obserwowanych niczym w kinie zwierzęcych okazów. Architektura wrocławskiego bunkra charakteryzuje się także zwielokrotnieniem ringów, które determinują sposób poruszania się – krążenia niczym po ściśle wyznaczonym terytorium zwierzęcego wybiegu. Jego granice mogą być namacalne, mogą też być niewidoczne, ale oddziałują z taką samą mocą.

Imprint

| Artist | Netta Laufer, Tom Swoboda |

| Exhibition | Territory |

| Place / venue | Wrocław Contemporary Museum, Wrocław, Poland |

| Dates | 4 December 2020 – 8 March 2021 |

| Curated by | Agata Ciastoń |

| Photos | Małgorzata Kujda |

| Website | muzeumwspolczesne.pl/ |

| Index | Agata Ciastoń Netta Laufer Tom Swoboda Wrocław Contemporary Museum |