Martina, Agnieszka and Anna

Anna Hulačová, a sculptor, was born in 1984 in Czechoslovakia. She grew up in Kasejovice near Blatna, spending her time in a brickyard located on her grandfather’s land or working the fields with her siblings. Agnieszka Polska, a video art maker, was born a year later in Lublin. Both sides of her family come from the Lublin countryside, but her grandfather and grandmothers, in the early years of the Polish People’s Republic, made use of the opportunity provided by the state for getting an education and social advancement. In a similar period, Anna’s family in Czechoslovakia went through a brutal process of rural collectivisation, modeled on the Soviet example, and a grandma of Martina Smutna’s husband (Smutna is a painter born in Czechoslovakia, in 1989) decided to enroll in a local Collective for Agricultural Production (JDZ), one of the novel forms of organisation of farm labour. Martina, Agnieszka and Anna are co-creators of the first part of the exhibition, drawing on vicissitudes of their families intertwined with histories of modernisation, industrialisation and electrification as well as social advancement and emancipation of rural women.

Part One

Edible, Beautiful, Untamed seem to promenade down the monumental, post-industrial hall. The Edible is wheat emancipated from the imperative of usefulness and the regime of industrial production. Just as the other monstrous characters, it sweeps the floor only thanks to flatly distributed roots. The spikey Untamed is only a little less tall. It received the name to honour the thistle, leading its partisan life on fringes of fields, never having allowed itself to become a human resource. The Beautiful, in turn, bears a name alluding to a daffodil, playing a decorative role in human gardens. With green shoots crossed behind its back, it calmly watches the objects below. As a trio, hovering over human heads, they resemble shepherds or gardeners tending to things found between them. They bring to mind an effect of an apocalyptic mutation or representatives of a foreign civilisation, introducing a new order on Earth, based on a different set of values. They are like Oankali, extraterrestrial creatures described in the late 1980s in Octavia Butler’s science-fiction trilogy, Xenogenesis.

Concrete objects in-between could be engines abandoned in the field – tractor or harvester parts – but there is something uncanny in their shape. Oblong organic forms suggest that rather than having been constructed, they have grown. In this, they are reminiscent of biotechnological products, operated by characters in Butler’s novel. Oankali used the living matter in the way humans employ machines, without divisions between ecology and technology. Their spaceships were growing, living organisms, with a ‘circulation system’ feeding the creatures onboard and recycling all refuse. When we take a closer look at the ‘machines’, we might observe that their concrete bodies also host various forms of life: eggs, seeds and cereal ears. Openings in the solid structure of the sculptures give way to organic ‘fluids’, executed in concrete-contrasting ceramics, as well as all kinds of feelers and projections. Finally, it offers shelter to small anthropomorphic thistles, ears of wheat and daffodils – miniatures of the three characters hovering over the whole composition.

Butler’s Xenogenesis speaks about the coming of a new, posthuman era, in which humans have to co-evolve with extraterrestrials in order to survive. Conceivably, Edible, Beautiful, Untamed is a vision of an outcome of such a mutation; providing hope for a posthuman future in which we have an opportunity to learn non-hierarchical ways of being in the world. A future that blurs boundaries not only between technology and organicity, but also the human and the non-human.

However, Anna Hulačova’s futuristic vision stems from history, realness and landscape of Czechoslovak, and later Czech countryside. Its starting point is the process of industrialisation of agriculture after the Second World War, related to forced collectivisation, and conducted on the Soviet model (also, in other countries of Central and Eastern Europe to varying extents): an analogue to Stalin’s great plan for transformation of nature. Individual households were then combined into great collective farms that were monocultures, with an intensive use of artificial fertilisers, pesticides and heavy oil-powered equipment. They aimed to increase efficiency and productivity, and led to soil degradation and erosion as well as air pollution. In the wake of the Velvet Revolution (1989), Czechoslovak state farms were entirely privatised and became part of the global chain of food production, following the logic of profit and further exploitation of the natural environment.

Hulačová draws on her difficult family history, viewing it from the perspective of contemporary environmental disaster. She combines allusions to SocRealist and social modernist art, enthusiastic about modernisation, with surrealist motifs which, in turn, debate rational and techno-enthusiast narratives. A concrete relief – the final element of the installation – represents a field approached by three chemicals-spraying machines. On the left, there are two long-haired figures, with their heads apparently conjoined and facing away from the viewers, likely referring to the question of rural collectivisation and emancipation of rural women. Opposite, even furrows of ploughed soil are woven into a girl’s braid reached by a clawed animal hand. This seems to be an allusion to more sustainable, pre-modern methods of soil cultivation and different relationships with other species. The landscape for a world taken from Xenogenesis is distinguished by one significant fact: it lacks representations of aliens. The concrete relief does include a ceramics bee, reminiscent of representations of aliens, and a pencil-drawn cereal dancing in a circle, but hybrid characters are composed solely from pieces of farm equipment, humans, insects and plants native to the village familiar to the artists. We are situated within a fantasy on a future evolution of the familiar, rather than in an imaginary visit from extraterrestrials.

In this world, who are the women depicted near-by, in portraits painted by Martina Smutna? Perhaps, they are matrons and ancestors of a future hybrid lineage, telling their descendants stories about the past. Emancipation of non-human beings in an agricultural landscape must have been preceded by the emancipation of rural women from patriarchal social structures. After all, the history of rural modernisation, brutal towards nature and a greater part of peasants, was also connected with an undermining of traditional relations between females and males or with a widening of professional opportunities for rural women. In Czechoslovakia, one of them was a grandma of Martina Smutna’s husband. Recognising the emancipatory aspect of the process of rural modernisation and her family history, the artist makes an attempt at reclaiming SocRealist representations, created in support of a new social order. SocRealist painting inverted patriarchal imaging conventions, but as an implementation of a top-down cultural politics, thereby missing a possibility of representing our grandmas’ authentic experiences of emancipation and social advancement. This might be the reason that in her 2018 large-format canvases, drawing on SocRealist aesthetics, Woman with Hay and Woman with Spade, the artist decided to strip her protagonists of their facial features. Returning to the same motifs for the Duby smalone [Fiddle-Faddle] exhibition, Smutna made a different decision.

Her new works are smaller, pastel portraits of women with haggard eyes and tight lips, depicted against tractors raising clouds of dust (Harvest 1, Harvest 2). The protagonists seem to embody a difficult path, marked with hard physical labour, of our rural grandmothers’ social advancement. A counterbalance for the hardship is provided by images of mutual support offered by rural women’s communities (Break). A scene representing people gathered around a huge tractor’s wheel could be found on a poster promoting an official organisation of rural girls. One should not forget the fact that in offering opportunities for advancement to women, the real socialist state expected their involvement in processes of agricultural industrialisation. In the final painting (Love Story), a tractor’s wheel supplants a character’s head. This might already be the hybrid being from the future, in whom the boundaries between humans, nature and technologies will have been ultimately blurred.

The boundary blurring is also one of the motifs in Agnieszka Polska’s video A Thousand-Year Plan, alluding to the history of electrification of rural areas in Poland in the immediate aftermath of WWII. Electricity is represented as a fascinating force of nature, intertwined with human histories. In the artist-made world, small fires hover over the heads of human and animal protagonists, suggesting a co-existence of humans, nature and the energy grid as a totality: a single structure that does not differentiate the artificial from the natural. According to Jakub Majmurek, “in Polska’s video, electrification is not an act of supremacy over nature, but rather a ‘plugging-into’ naturally produced flows of energy.” Electricity here is a kind of magic. Natalia Sielewicz terms this sort of work ‘magical SocRealism”, and Majmurek observes that “every truly radical technological revolution is, in a sense, surreal, as it momentarily erases the boundary between magic and technology, waking world and dream, dreams and reality.” Today, we return to it with good reason, searching for other ways of building relationships with the worlds of nature and technology.

Nonetheless, human characters operating in this complex structure once again have a real genealogy that is close to the artist. They are in a forest in the Lublin region. The story takes place parallelly on two screens, depicting the perspective of two couples. A man and woman engineer are planning the electrification of Stasin, verifying their central plans on the ground. She speaks about her family village she had left, having received an opportunity of social advancement. Just like Agnieszka Polska’s grandma, her name is Wiktoria. The other couple are members of an anti-communist underground. Both couples imagine the impending technological revolution and their dreams seem to be filled both with hope and fear of the new dawn that will never be put out again.

***

Iza, Karol and Kasia

Iza Tarasewicz comes from the Podlasie region. She was born in 1981 and brought up in the village of Kolonia Koplany near Białystok. Like Anna Hulačová, she spent a large part of her childhood in the village brickyard and lived in a multi-generation house with a small farm. She became a sculptor. Karol Palczak, a painter born in 1987, comes from the village of Krzywcza in the Podkarpackie region. Both artists returned to their home places after studies to live and work. Pieces in the second part of the exhibition have them go back to a more remote past, seeking out the history of their ancestors several generations before, alluding to folk customs and assessing the histories of modernisation and accelerated technological development from the vantage point of the places of their current residence. Their works are accompanied by an action by Kasia Hertz – an artist living in the Białowieża Forest, whose family comes from Lida in the current territory of Belarus. Her performance, created in collaboration with people of Białystok, draws inspiration from local rituals.

Part Two

The space is filled with monumental yet intricate sculptural installations. Their main motif is palms – tens, hundreds of palms. Made of steel and brass, they allude to forms of farming equipment such as hay rakes. They are also a reminder of times from before modernisation of the countryside – the non-mechanised world where everything was done by hand. Who owned the hands? In 1832, count Zygmunt Krasiński claimed: “our peasants are machines”. Human machines, those ‘breathing tools’, could not refrain from work. “One had to serve with one’s whole person,” Kacper Pobłocki affirms, but “the one who wanted to demonstrate that they are great lords boasted that they had so many thousand souls…, except that souls were not at stake, but rather bodies.” Most of all, hands.

Another element interwoven with the motif of palms, repeated and returning in subsequent works, is cereal. According to Pobłocki, “the manner of food production is the source of the whole social order. Cereal can be stored for long periods of time, transported at large distances and its harvest period is distinct and relatively short.” The scholar argues that it is easier to organise the year-long treadmill of labour around such plants. “The ancient class state could practically be reduced to one function: a great granary. It dealt in redistribution of food cultivated by the enslaved settled population: taking from some and giving to others.” Cereal in Iza Tarasewicz’s sculptural installations is still unripe. The artist has just gathered it in Koplany, her home village, which was a site of a manor farm for three hundred years. It has been pulled out with its roots – uprooted, as the artist calls it – since contemporary industrial cultivations are such, wholly missing in local species.

A centrepiece of this part of the exhibition is an installation representing an old ladder wagon filled with ‘several generations’ of palms that are trying to mount one another. As if they wanted to reach a satellite above then – “a new, solar panel powered world”. The representations of palms assume the most suggestive shape here, resembling crawling body parts from the living dead. Folk spectres become a metaphor for peasant serfs deprived of a decent life. According to the artist’s intention, Ruins and Promises is also a piece referring to contemporary megalomaniac attempts at conquering space by billionaires, seen through the eyes of a female resident of a Podlasie village. It points toward a continuity of the system of organisation of human labour based on exploitation.

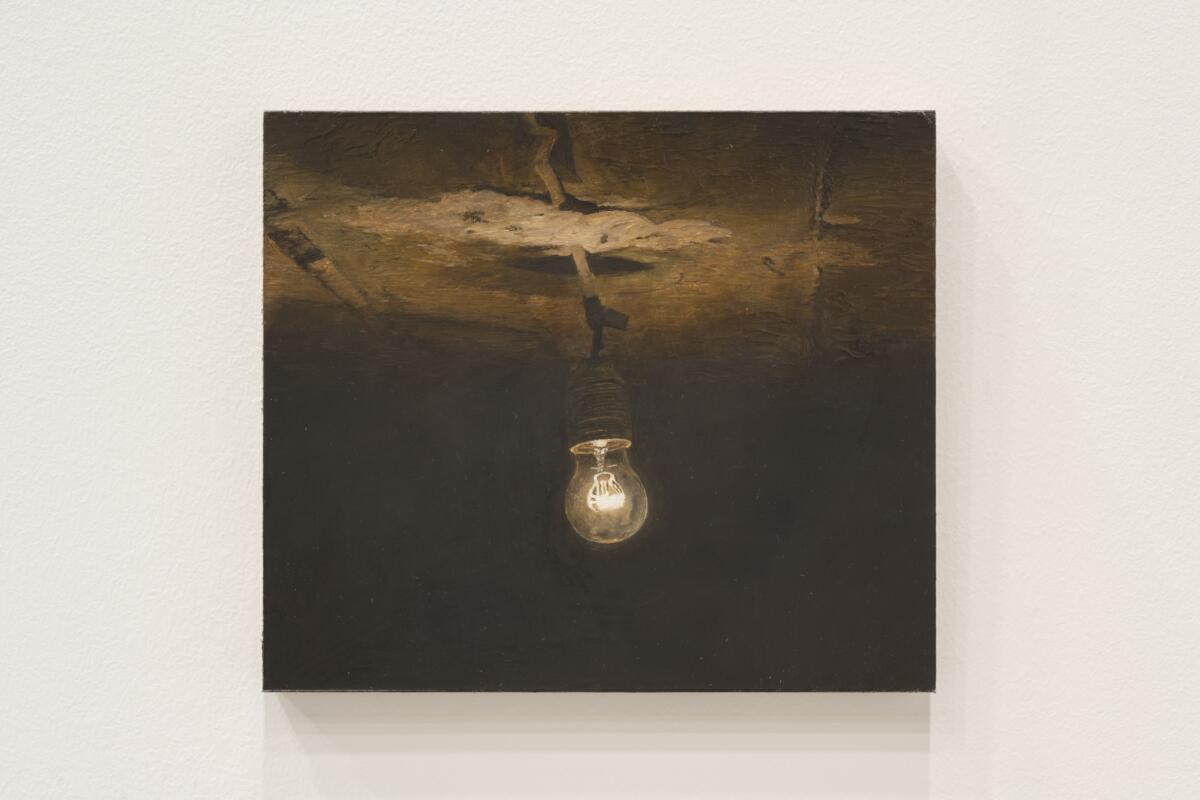

On the other side of the hall, three small oil paintings hyper-realistically render the same lightbulb, hanging from a ceiling of an utility room in Krzywcza. An outcome of the great technological revolution dreamt about by the protagonists in Polska’s film. Plaster is flaking off the ceiling and the lightbulb seems to barely illuminate the dark, provisionally connected to a raw cable. Karol Palczak paints almost nothing but his home village. Krzywcza in the Podkarpackie region is currently one of the poorest rural municipalities in Poland. Paintings depicting the artist’s immediate vicinity become a document of an unfinished modernisation of the peripheries. Together with Tarasewicz’s work, they may draw attention to power resulting from access to infrastructure and exclusion caused by its lack. They highlight the question featured in A Thousand-Year Plan: “Which social groups and institutions control technologies and impose the framework of communal life?”

Climbing palms in Tarasewicz’s central installation make use of a previously undescribed support: more than a dozen scythes placed at the back of the wagon. Scythes, serving as a weapon where necessary, symbolise numerous peasants’ revolts. Apparently, peasants living in the hardly accessible marshes of the Podlasie region were deemed “the principal revolters of the whole Commonwealth.” However, open armed revolts, according to Pobłocki, was the sole domain of men. Women employed means that eluded confrontation. “The most dangerous weapon of the vulnerable in their silent war with the state was arson.” Notably, the artist who draws on a powerful allusion to armed rebellion is a woman, while burning objects are a recurring subject of Palczak’s paintings. Two represent burning dummies, referring to the folk custom of drowning the Marzanna doll. The third one has a car wreck on fire and in clouds of smoke.

Rituals are characteristically unchangeable, repeated through tens or hundreds of years, sometimes losing their original context. In Palczak, the burning dummy is accompanied by a man called Czesiek. A construction supermarket bucket unequivocally situates the scene in the present. Perhaps, the painting is an expression of yearning for the time marked by a cyclicality of seasons; when the drowning of the Marzanna was supposed to invoke spring. Perhaps, A Burnt-out Car endows the ritual with a new dimension. Similarly, local rites are intertwined with the contemporary thanks to people invited by Kasia Hertz to participate in a communal action in the gallery space. Moving between the past and the present, whisperers become characters from the universe of internet trolls and cyber-elves, trying to separate the truth from fake news by means of customs inspired by those from the Podlasie region. In creating their communal poem, they make use of the local rituals of enchanting, ‘dis-chanting’ the poetics of internet language.

Cyclicality of time and the rhythm of monotonous yet communal labour in the countryside are referred to also in Looped Procession, three wheels, suspended in space and modeled on folk ornaments (the so-called ‘spiders’), decorated with cereal and palm-shaped objects. The wheel-enclosed cyclicality alludes also to the folk mazurka dance and its trance-like repetitions. The dance moves reflecting the rhythm of labour were once the way for enslaved peasants to let go of the trauma of life in serfdom and gain a space of free expression. In Tarasewicz’s interpretation, the wheels are also giving hope for regenerative powers of the soil, survival and the cyclical rebirth of life and collectivity after the foreseen collapse of contemporary agro-economics.

Agnieszka and Eglė

Agnieszka Brzeżańska (b. 1972) was raised in her grandparents’ house in Mława, on a street that had once been a separate village. The artist’s grandpa worked on electrifying the street, but Agnieszka is fascinated with objects, rituals and forgotten folk knowledge of home soil originating in epochs preceding the period of modernisation. In the final part of the exhibition, her works are displayed alongside a video by the Lithuanian artist, Eglė Budvytytė (b. 1982), produced at the Curonian Spit National Park. Both artists seek out ways of overcoming anthropocentric hierarchies, building different relationships with the land and inviting visitors to their spaces of rest.

Part Three

Solar flares are caused by a sudden emission of enormous amounts of energy in the Sun’s atmosphere. If sufficiently powerful and directed at the Earth, they may lead to power grid failures. A large-format painting depicting solar flares dominates the following room of the exhibition. It introduces an ambience of anxiety as well as, unlike Tarasewicz’s satellite symbolizing the conquest of space, reminding us about our dependence on other planets and the place we actually occupy in the universe. Especially that it is juxtaposed with a globe that seems tiny against its background. Watching the sky brings to mind the movement of heavenly bodies and resulting natural time, a return to which is postulated by Agnieszka Brzeżańska. Already the starecase glitters with the artist’s recurrent slogan: Change Your Calendar. Change Your Mind. Change Your Government.

The globe, as a part of the installation, is supported by one of several figures crowded on a narrow cube. Forebears are rounded ceramic figurines of many heads, spreading in various directions like feelers. Those smiling amorphous beings are a metaphor for common matter, of which everything is composed. They also refer to the American biologist, Lynn Margulis, and her theory of symbiosis as the driving force of evolution. Margulis opposed competition-orienten views on evolution, underlining the significance of symbiotic or cooperative relationships between species. Brzeżańska also seeks out connections between humans and the ground among archeological finds on the territory of contemporary Poland. In her series Ma Terra, she creates vases and ceramics objects inspired by the finds, decorated with shapes of human breasts and feet. They may be an allusion to the time when humans had still perceived themselves as part of nature.

Brzeżańska is also interested in herbalism, formerly a specialist knowledge considered by country folk as part of magic and transmitted through generations. A knowledge that could also serve as an instrument of resistance; next to arsons, women often chose poison as their preferred weapon against the overlords. But, first and foremost, a knowledge in the service of healing, both physical as well as mental illnesses, caused by heavy, chronic stress which the peasant serfs had to endure. Pobłocki claims that every era has its proper disease. In serfdom Poland, where depression was unheard of, the disease was the so-called Polish plait. Depression is the disease of modern capitalism. The artist invites visitors to rest on hay seats in a pleasant space, surrounded by fabrics in earthy colours, offering an oatstraw infusion (filling up also some of the exhibited ceramic vessels), used to this day in case of mental fatigue and exhaustion caused precisely by stress and depression.

A screening room neighbouring Brzeżańska’s installation presents Eglė Budvytytė’s video Songs from the Compost: Mutating Bodies, Imploding Stars. Working mainly at the intersection of poetry and performance, the Lithuanian artist represents an interpenetration of human bodies and their resident environment. A tangled group of non-binary performers travels moss-covered pine forests and seaside dunes. They move together, as a choreographic entity, changing shapes and pushing ahead – at times, like crabs – on the ground. Drown earthwards, they often assume horizontal position. Subverting human verticality and domination over the surrounding, they unfold human silhouettes in the landscape, when moving along the dunes and water. They appear to be in a state of continual metamorphosis.

A hypnotising music accompanies the poetic composition that transmit the desires of the shape and gender shifting being taking on various voices and non-human embodiments. At one point, her name is medusa, becoming a stone at others. Apparently, “in ancient times, humans believed that the world, be it human, or non-human, is made up solely of sentient beings. Objects in the modern sense of the word did not exist. Even the stone was not regarded as a mute, passive, impersonal thing. An echo of the approach can be found in the Polish countryside as late as the 20th century, for instance, in phrases of the kind: ‘when stones grew, they were soft’.” (Pobłocki)

The shape-shifting group is wearing clothes that have been dug underground for a few months. Their appearance is a result of labour of earth-residing microorganisms and the text of the piece is yet another allusion to Margulis, perceiving human bodies as ecosystems composed of collaborating bacteria and drawing attention to the cooperation between all unicellular organisms. By means other than Hulačova’s pieces one floor below, the film refers also to posthuman mutations described by Butler as well as to the figures of hybridity and the cyborg put forward by Donna Haraway. Through text and choreography, the piece explores non-human forms of consciousness and different dimensions of a symbiotic relationship to earth and nature such as co-dependence, sensitivity, care, death and decomposition.

Translated from Polish by Piotr Mierzwa

Imprint

| Artist | Agnieszka Brzeżańska, Eglė Budvytytė, Kasia Hertz, Anna Hulačová, Karol Palczak, Agnieszka Polska, Martina Drozd Smutná, Iza Tarasewicz |

| Exhibition | Duby smalone [Fiddlesticks] |

| Place / venue | Arsenal Gallery Power Station (elektrownia) |

| Dates | 30.06 - 3.09.2023 |

| Curated by | Katarzyna Różniak-Szabelska |

| Photos | Tytus Szabelski-Różniak |

| Index | Agnieszka Brzeżańska Agnieszka Polska Anna Hulačová Arsenal Gallery Power Station Eglė Budvytytė Karol Palczak Kasia Hertz Katarzyna Różniak-Szabelska Martina Drozd Smutná Tytus Szabelski-Różniak |