[EN/HU] ‘Don’t lay him on me…’ by Dominika Trapp at Trafó Gallery

![[EN/HU] ‘Don’t lay him on me…’ by Dominika Trapp at Trafó Gallery](https://blokmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/08-1200x1800.jpg)

[EN]

Grave reality

text by Cara Spelman and Balázs Prokk

Patriarchy is a political, legal and economical ideology, wherein men, and not women, are the subjects who can legitimately exercise their will and power. Legitimate constraints to this will and power are therefore solely determined with the interests of men, as the assumed subjects of patriarchy, in mind. Just as men see themselves as the leader of the household, similarly, society is dominated by men’s organisations. Configured within the patriarchal system as men’s property, women have been assumed to be the object of men. They are therefore acted upon, rather than being acknowledged as actors themselves, and are expected to bear everything from their sale to violence.

Women can only associate during their co-working labour hours. In the Hungarian peasant culture, for example, the place of such groupings is the fonó (weaving room). Even though the weaving room is a space for these women, the patriarchal apparatus of censorship is still felt here, as the women’s freedom to communicate their struggles is constrained somewhat by a fear of patriarchy, meaning their communication of this must be indirect. The women therefore make use of imaginative and creative ways to indirectly communicate their experiences, which we can see in the use of metaphors and metanyms by narrators in ritual games and especially in folk songs. The grave reality subtly communicated in these games and folk songs can be heard by those listening sensitively. While women are together and communicating in these spaces, the grip of patriarchy still mediates their communication, as they fear that directly speaking about their experience might result in the very real threat of violence from men. Therefore, a conspiracy of silence, fueled also by shame and stigma, surrounds direct testimonies of women’s experiences and suffering, meaning that women’s narratives must be indirectly relayed, or not relayed at all:

“If your heart is full of sorrow, don’t tell everyone,

complain to the Heavens, because it won’t tell anyone.”

Asszonyok könyve (Women’s Book) is a collection of many women’s stories collected and published by the folk-anthropologist Olga Nagy. The tangible intimacy of these stories results from a sense of trust, as the stories have finally escaped the grasp of men. However, recounting these narratives of trauma is grievously taxing. Wounds thought to be healed often re-open, with mental and physical traumas of the past made present in their re-telling: lives of conflict and oppression, fragmented histories and personal tragedies all re-emerge for the women recounting these events. These confessions encompass the reader also, as traces of trauma are relived in its retelling.

Searching for these formative traumatic moments, we became aware of two distinguishable narratives: one of them is dominated by frozen passivity, wherein everything remains unchanged. However, there are quite a few stories in which the protagonist resolves her conflict. The tension between these two responses to trauma made it feasible for us to create an interpretative framework for looking at these narratives and the time-consciousness of their narrators.

These life-changing moments repeat themselves within the framework of the mind. These formative moments are also present in the folk songs. In this example, we become aware of attempts at an action which never comes to pass:

I was leaving for You three times,

But I could not even get closer to your window.

Something caught me at the gate,

So, (…) I could not even speak a word.

Dominika Trap, ‘Don’t lay him on me…’, exhibition view

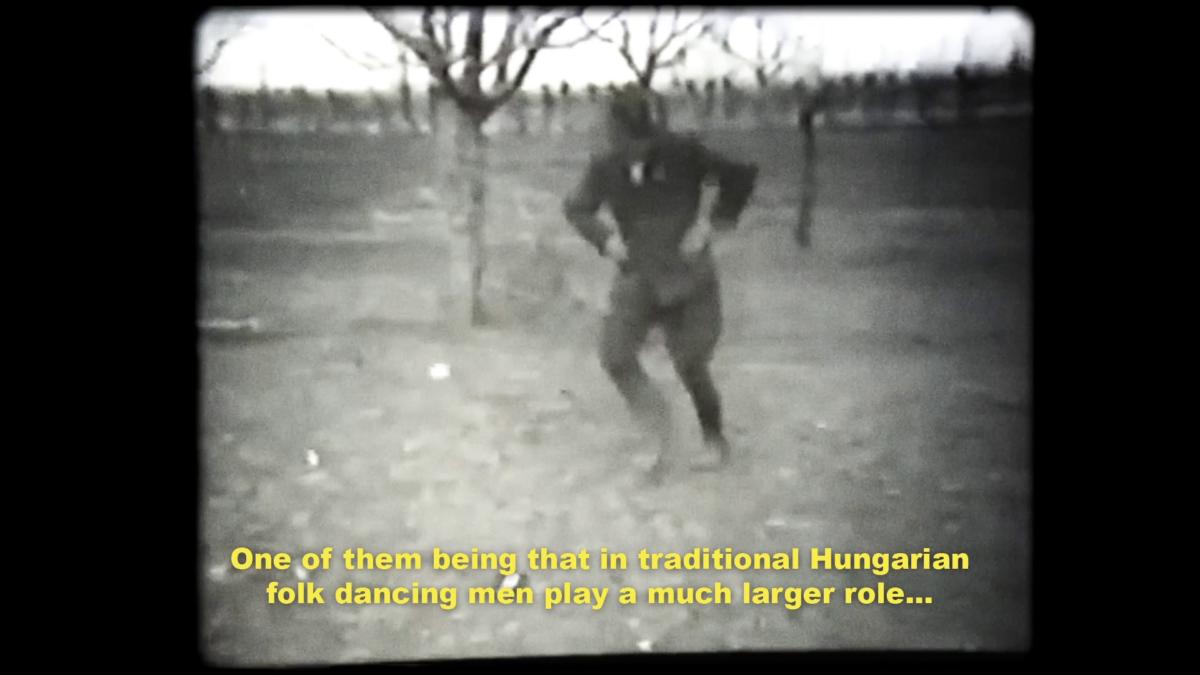

During months of labour, the difficult lifestyle of the peasants is strictly planned and regimented. The peasants’ self-consciousness are convulsing into the straight grooves of the plow, and it could be liberated only through dancing movements. Jumping and swaying together relieves people from their daily struggles somewhat, and dancing becomes the closest thing to freedom the peasants experience.

When Kata Szivós in her ‘Maiden’s Dance’ choreography adopts the virtuosity of the young men’s dances, she transgresses the limits of patriarchy. The subversive nature of this act is evident when we consider that the man (vir) is the root of virtuosity. However, this aesthetic characteristic of the men ought to be joined with self- and collective-responsibility too, (ie. virtue). Patriarchal configurations of virtuosity in men often involve an extroverted kind of virtuosity, connected with strength, bravery and virility. In women, however, patriarchal displays of virtuosity are traditionally connected with passivity, discreteness and virginal purity, a hemmed-incomplement to the virtuosic man’s virility.

There are some records of women dancing what are traditionally considered men’s dances. Both the verbunk of Mariska Szuromi (Tyukod) and the legényes of Ibolya Jaskó (Györgyfalva) are well known among folk dancers, and their dances are recurring elements of other choreographies too.

Kata Szivós’ choreography, which features improvisational, female solo dance, stems from this tradition also. Her subversion of traditional gender roles in Hungarian folk dance is an act of courage and agency under patriarchy, and so it necessarily raises important questions surrounding two moral conceptions of the roles of women in society.

In rural Hungary, it is possible to identify these two different conceptions of morality. Which conception of morality present in a given community may depend on the size and demands of that community. Dogmatic morality fits perfectly into the prescriptive system of patriarchy, in which girls are constantly learning about women’s roles, from children’s play to women’s circle-dances to religious rites. In contrast to this conception of morality, we can identify a more locally-organized, practical morality, one that emerges during and after wartime. During these times of conflict, women often have had to adopt roles traditionally attributed to men in patriarchal societies, which meant that the subversive solo dances of the aforementioned female dancers were not only tolerated, but even accepted by their community.

However, the equilibrium between the dogmatic and the practical conceptions of morality is very fragile. Practical morality, which can be liberatory for women, is necessarily disruptive of the patriarchal order. In response to its disruption by this practical morality, patriarchal dogma begins a process of fervently attacking this attempt at liberation, beginning a process of scapegoating and systematic witch-hunts. At the end of this unconscious collective violence, the old order is restored, and the lives of the tragic victims are conserved only in ballads by community of the fonó. Practical ingenuity and liberatory attempts are stitched up once more and the stories of these attempts at freedom become ballads of warning against further failed attempts. Subversion of the patriarchal order is discouraged, as only the negative implications of past attempts at resistance are passed on through ballads.

Dominika Trapp’s exhibition gives new life to the silenced memoirs of these women.

The film is a documentation of the choreography titled ‘Leányos’ by Kata Szívós. It was directed by Noémi Varga in coproduction with Dominika Trapp for her solo exhibition at Trafó Gallery titled ‘Don’t lay him on me’ (2020).

[HU]

Pellengérre állított valóság

Prokk Balázs

Patriarchátusnak azt a politikai és gazdasági berendezkedést nevezzük, amelyben a férfiakat születésüktől fogva a hatalom akarására és legális gyakorlására nevelik. A hatalom gyakorlásának jogilag helyes korlátait egyedül egy másik férfi, illetve a közösség érdekének hatóköre szabja meg. Miként a háztartást a férfi, úgy a társadalmat a férfi társaságok uralják. A patriarchális berendezkedésben a nők a férfi tulajdonát képezik. Ezért a nőkkel, – mint minden más tulajdonnal – bármi megtörténhet: a kiárusítástól az erőszakig.

A közösség nyilvános tereiben a nők csak a közös munkavégzés idejére társulhatnak. A magyar paraszti kultúrában ilyen csoportosulások helyszíne például a fonó. A fonóban szinte minden elhangozhat és majdnem úgy, ahogy az csakugyan megtörtént, de a női tapasztalatok szabad megosztása itt is korlátozott. A cenzúra mechanizmusa a női közlések szabadságának szűrője. Így, a rituális játékokban, valamint a népdalokban megénekelt metaforák, és metonímiák által megjelenített és elbeszélt történeteket a képzelőerő már szükségszerűen módosította. A tényleges valóság csak egy-egy hajlításból, témaválasztásból cseng ki az avatott fülek számára. A férfiak hatóerejének félelmetes szorítása a női közösségek együttlétét csak a virtualitásban engedi kifejeződni. Így, a női realitás, csak negatív, közvetett tanításokban élhet tovább, a cinikus csend tanításában:

„Ha szíveden sok a bánat, ne mondd el azt fűnek-fának,

panaszold el a nagy égnek, mert az nem mondja senkinek.”

Nagy Olga Asszonyok könyve című gyűjteményes kötetéből áradó személyesség nem más, mint a félelem hallgatásából kitörő bizalom. Az elbeszélések elevenségének azonban fájdalmas ára van. Az összeforrt sebek felhasadnak, majd a lelki és fizikai traumák megelevenednek: a nyomasztó konfliktushelyzetek, meghasadt élettörténetek, és tragédiák felelevenítése újra szétzilálja az elbeszélő asszonyok értelmét. Ezen elbeszélésekből kiáradó nyomasztó hangulat az olvasót is körülöleli, s a szöveg nyomai egy még mindig hasogatóan fájdalmas eseményre mutatnak; egy pillanatra, amikor az értelem elillant, s összezavarodott minden.

Ezeket a traumatikus, s egy teljes élettörténetet átható pillanatokat keresve kétféle elbeszélésre lettünk figyelmesek: az egyikben úrrá lett a dermedt passzivitás, s így minden maradt a régiben. Azonban szép számmal akadtak olyan történetek is, amelyekben valamiként a főhősnő megoldotta a konfliktushelyzetet. E két személyiségtípus közötti feszültség hozta mozgásba azt az értelmezési keretet, amit az egyszerűség kedvéért idősíkoknak, illetve mozgástérnek hívtunk.

Az asszonyok által felelevenített sorsfordító pillanatok tehát a tudat terében újra lezajlanak. Erről adnak számot a titkokat metaforákkal sejtető népdalszövegek is. Itt egy olyan eseményről hallunk, ami ugyan folyamatosan zajlik, de – talán jó okkal – mégsem történik meg:

„Háromszor is elindultam s elmentem

Ablakidhoz még közel sem mehettem

A kapuban úgy elfogott valami.

Hogy egy árva szót sem tudtam szólani”

A munkahónapok ideje alatt a kemény paraszti életforma szorítóan kötött. A szántás nyílegyenes barázdáiban feszülő öntudatot egyedül a tánctérben helyet találó ugrások, lábkörök és páros forgások oldják el a hétköznapok gondjaitól. Ezért a tánc a megtapasztalható szabadság legmagasabb közösségileg elfogadott formája.

Amikor Szivós Kata a férfitáncok virtuozitását átemeli Leányos című koreográfiájába, átlépi a patriarchátus korlátait. Úttörősségét a szó eredete is tanúsítja, ugyanis a virtuozitás szó gyökében a férfi (vir) lelhető fel. E jól látható, esztétikai rátermettségnek azonban a morális virtussal is egybe kellene vágnia. A férfi, annyiban erényes amennyiben képes önmagáért és közösségéért is felelősséget vállalni. Ezzel egyidejűleg a női sors alávetettsége az erény fogalmában is tetten érhető, hiszen az a szűzies tisztaság fenntartását foglalta magában.

Talán sokak számára meghökkentő lehet, ám a férfitáncokat táncoló nőkről még filmfelvételeink is vannak. A tyukodi Szuromi Mariska verbunkját, vagy a györgyfalvai Jaskó Ibolya legényesét sokan ismerik, és visszatérő elemei színpadi koreográfiáknak. Tehát Szivós Kata koreográfiája – melynek célja egy improvizatív, női szólótánc létrehozása – szintén a hagyományból fakad. Önmaga felszabadítása mégis több fontos diskurzust tesz aktuálissá.

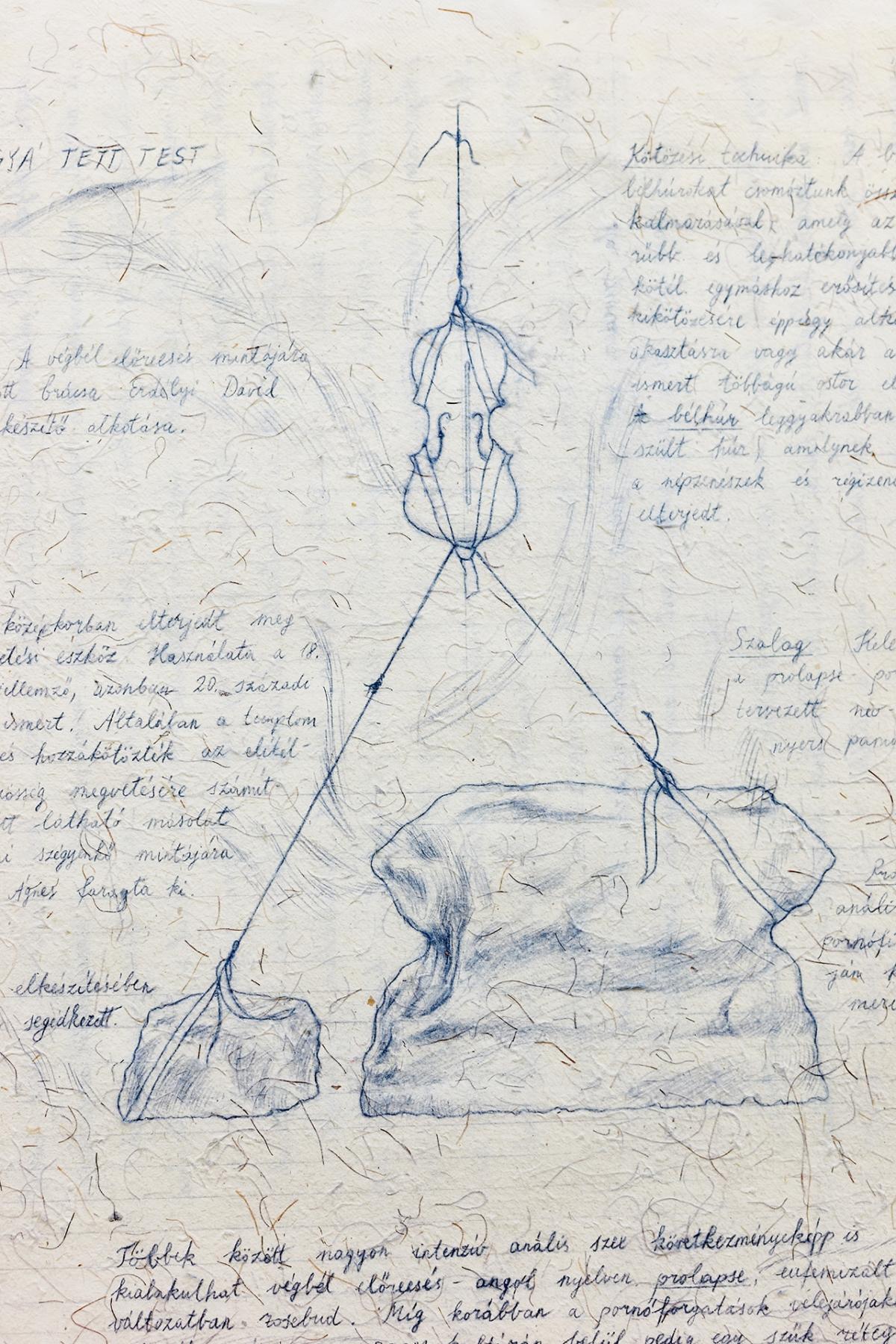

Exhibition view. In the foreground Dominika Trapp in collaboration with Richárd Kránicz, ‘The Body Perceived as a Fetish Object’, 2020, installation

A magyar népi hagyományban két különböző módon szerveződő morált érhetünk tetten. A dogmatikus és praktikus morál közötti különbséget elsősorban a közösség mérete, másodsorban a szükségszerűség határozza meg. A dogmatikus morál tökéletesen illik a patriarchátus előíró rendszerébe, amelyben a lányok folyamatosan tanulják a női szerepeket: a gyermekjátékoktól a karikázókon át a vallásos rítusokig. Ezzel szemben áll a lokálisan szerveződő, praktikus morál, – például háború ideje alatt, és utána – amikor a nőknek szükségszerűen magukra kellett venniük a férfi szerepeket is. A fentebb említett táncosokat jól láthatóan megtűrte, illetve megbecsüli közösségük.

Azonban a dogmatikus és praktikus morál közötti egyensúly nagyon törékeny. Ami az asszonyok számára gyakran praktikus haszonnal járna, az a férfiak közössége szempontjából rendbontó, s ezért elítélendő. Abban a pillanatban, amikor a dogmatikus vélekedés uszítássá silányul, az a praktikus kiteljesedés ellen fordul, és elkezdődik a bűnbakképzés, illetve a boszorkányüldözés. E folyamat gyakran gyilkossággal, illetve öngyilkossággal végződik. Az öntudatlan közösségi erőszak végén visszaáll a régi rend, és a tragikus sorsú áldozatok életét a fonó közössége átülteti egy balladába. A praktikus leleményt a felejtés szövi be, s az áldozatok története negatív tanításként él tovább a falu közösségében.

Trapp Dominika kiállításán fölelevenített asszonysorsok a titoktartó csend szorításából fakadtak.

Imprint

| Artist | Dominika Trapp |

| Exhibition | Don’t lay him on me… |

| Place / venue | Trafó Gallery, Budapest |

| Dates | 17 January – 1 March 2020 |

| Photos | Dávid Biró |

| Index | Balázs Prokk Cara Spelman Dominika Trapp Trafó Gallery |