In the midst of the second lockdown, towards the end of 2020 (when this exhibition was conceived) you find yourself absorbed in thought as you cross an unnecessarily busy London street. You don’t live in that part of town, nor have you had the privilege of working from home, but the news of the distinctively middle class preoccupation of lockdown home improvement combined with the government’s decision to keep department stores open as essential have planted a seed in your mind involving some curtain rods. As the light changes to green, you hurry to the entrance of the shop, distractedly already choreographing in your mind your errands for after you leave: pay the electricity bill (insistently not online), pick up food for the week (include ingredients to make a cake for your birthday; interrupt the rhythms of the everyday). But you don’t make it across the street; your body encounters a force stronger than you that pushes you out of the way and onto the ground, landing on your wrist, and the next thing you see is a glimmer of a face that stretches into a Cheshire cat grin as it utters feigned concern, having just pushed you, and disappears. Ambulance, hospital, codeine, two operations: your right arm (you are right-handed) has been fractured into pieces and a foreign object that aches with the cold weather is inserted. In time, when the waves of shock, then pain, subside, you will try to write the event off as one of those illogical absurdities of life that are a test of your patience with the world, but even as you do, your body will learn a set of postures not known fully even to yourself as it compels you to cradle your arm at night, or flinch at passers-by when they breach an imaginary threshold.

Does this image give you a sense of familiarity with this body, and maybe the owner of this body, down to the metal under its skin, even if all this lives in the space between two people’s imagination, where a fracture of this kind is a physical, though not a creative impossibility? Two people write this. But there is a point to this story (besides attuning you to the artifice of the autobiographical mode and the false proximity that it engenders), which is to draw your attention to the relieving posture in action: the behaviour of withholding from putting the damaged limb at risk without thinking of the event that caused the injury, and without needing to think altogether.[1] It is avoidance in crystallised form. The patterns and behaviours that characterise this relieving posture demarcate a space of the event felt through them, but not seen. In broader terms, it is a space not admitted to explicit knowledge, but undeniably obliquely present when made sensible through those recurring habits. The act of its negation is its acknowledgment.

It is the act of demarcating this space that is of interest to us, and the potential of the space itself. Politics may be considered to begin in abrupt events through which the disempowered redistribute the register of the sensible – i.e. redistribute what can be said and by whom, and what can appear as discourse and not noise.[2] This position, however, operates on the necessity of divulging a part of one’s subjecthood.[3] Only by making oneself transparent, by putting oneself on display, is the individual given a temporary stage to tell ‘the public’ their story that said ‘public’ expects to move through an arc of external acknowledgement and resolution.[4] Undignified in its request to perform pain, it does not recognise the existence of something beyond what is permitted to be made visible. All the while, the procedures of exclusion and the normative unconscious are left unrecognised as the cause for why the ‘reveal’ is required.[5]

Acts of translation into the language of hegemonic culture cannot touch and therefore do not acknowledge the part of sentience that is opaque and untranslatable into ‘clear’ discourse. We want this part of the sensible acknowledged in its shadowy form without the prerequisite of assimilation. If anything, it is to do justice to the incoherence at the crux of subjecthood.[6] We are, at least in part, strangers even to ourselves.

Avoidance is the site of upholding this shadowy form, yet leaving it the possibility of a dignified indistinctness. Instead, it proposes an encounter with the ways in which this implicit exists on the surfaces of the visible, repeats itself and ripples through the present. This may seem at odds with the very idea of an exhibition, directed towards making visible, externalised, quite literally exposed. The paradox of this endeavour is not lost on us. Yet the physicality of the space and the practices that mark it for this duration coalesce to feel the contours of this yet-unknown form that may still take other shapes in the future. Dispersed throughout a space below ground level and glimpsed in the labyrinthine passages of the basement that offers partial views, bodies of work resurface and return at different points. The exhibition behaves in a rhythm of a compulsive temporal working-through that repeats in an unresolved circular motion throughout the circular passage.

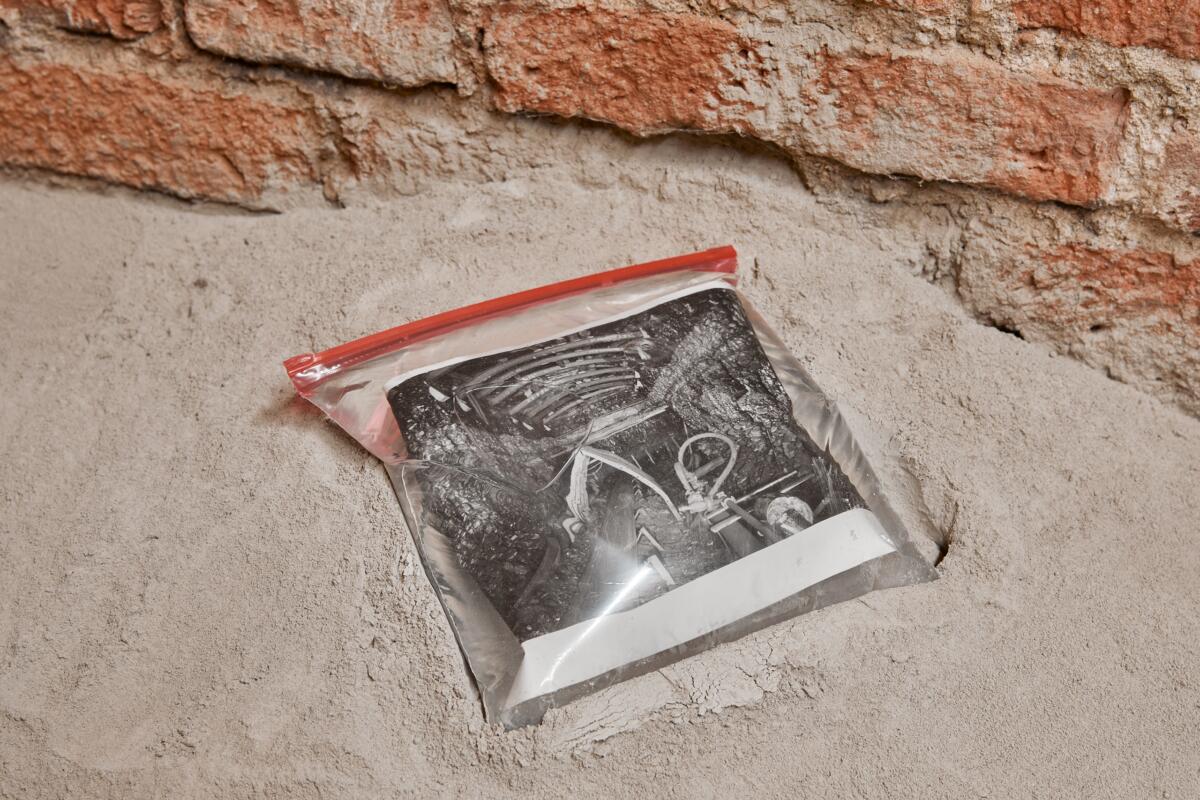

The space of the underground multiplies and caves in on itself through the work of Liv Preston, where it is both subject matter (more explicitly at first, before it fades through contact with water) and a vital resource (of energy, and of space for the imagination). Superimposed onto one another are Preston’s ongoing research into spaces of coal mining from the North of England (in the form of National Coal Board photographs of spaces now defunct), gargoyles as medieval graffiti, caving club cultures and dungeons in video games where their pixelated crevices become spaces for the mind to roam (or the minds of two children, now grown-up, and their left-behind drawings). The waterlogged images WATERLOGS – NCB MINE PHOTOGRAPHS become a sensed-but-not seen symptom of the basement’s contact with water and soil as its partial surroundings.

The works of Maria Loboda alter the fabric of the building, introducing an impossible passageway leading up (or down) from its deepest parts, and embedding themselves into its skin. Each of them refers to and revolves obliquely around cultural artefacts tied intimately to uncertain knowledge and hearsay: a rope punctuated with pheasant feathers found for the first time in Somerset, England in 1878 that may or may not have had curses woven into it together with the feathers; precious stones buried deep within the walls of Alhambra palace that archaeologists believe may or may not have been placed there on the order of the Nasrid dynasty anticipating the palace and dynasty both in ruin and splendour; a platinum flask that may or may not still contain both hydrogen and oxygen and which acts as a catalyst for a volatile reaction between the two gases.

The hydrogen finds itself likewise in close and in certain conditions hazardous proximity to the canvases of Alexandra Sukhareva, which are born through a corrosive process of an encounter with chlorine and light. A household disinfectant and toxic enough to have been used as a chemical weapon during World War I, chlorine corrodes, cauterises and removes rather than adds. This is the work of light: exposure to light – and light as a condition of visibility – and visibility as being exposed to the world – is marked by the surfaces as a corrosive, even exhausting, process. By speeding up the corrosion, paradoxically, the burnt-into surfaces made by Sukhareva’s mark-making protect the work from light alone doing this gradually, becoming an apotropaic device both in form and material substance.

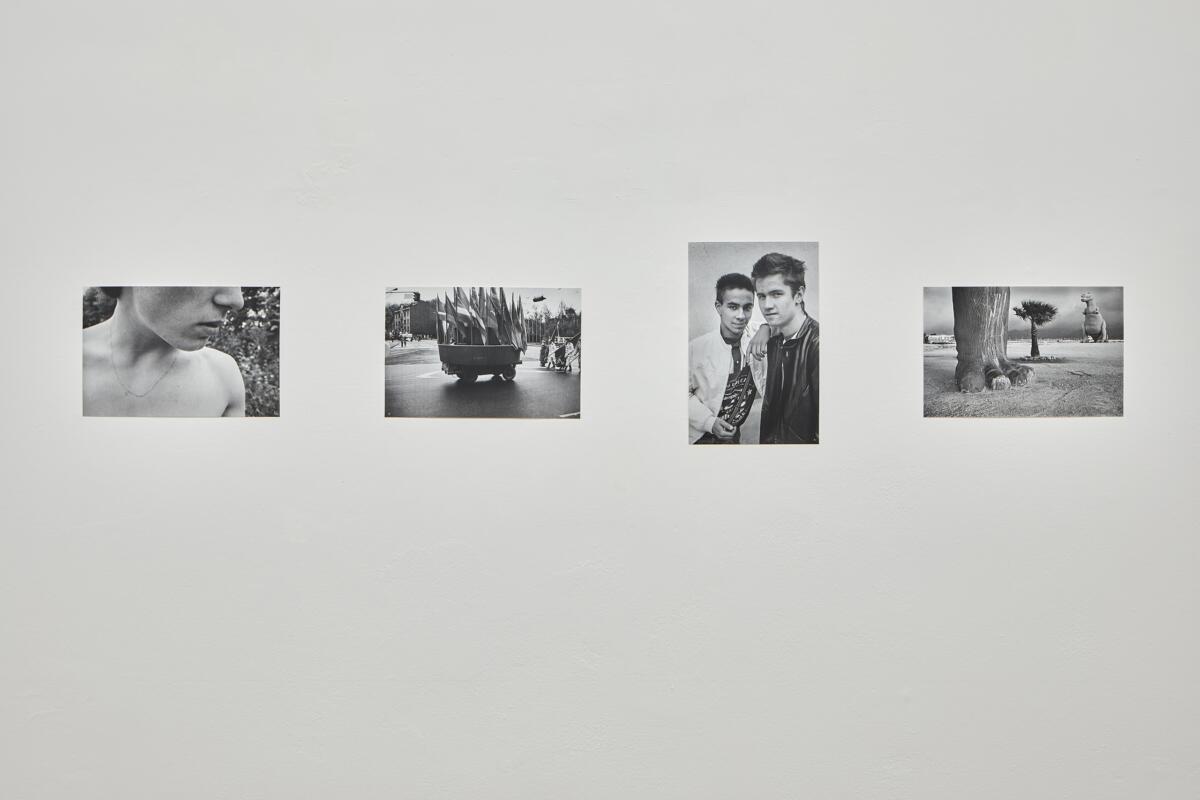

Celebrated for his official photographs of Lithuanian society under Soviet occupation, Virgilijus Šonta died before the country decriminilised homosexuality in 1993. His sexuality has been made ‘transparent’ in recent years through a series of articles and the circulation of the previously unexhibited parts of his archive, through which Šonta could easily be rendered an example of the process of reinscription as assimilation. Yet permeating his works are distortions of what appear as everyday moments – the warping of vision, ambiguity of glance, overexposure of light as well as fragmentation, displacement of time and place – all of which resist absorption. The play between the registers of ‘private’ and ‘public’ in the photographs undermines the perception of a subjective whole having been reached, instead doubling the artist’s identity. They function as a reminder that the light of the present has its own blind spots, as only the part of the past that appeases it is brought onto the centre of the stage.

From a blind spot to a sudden flash of light that overwhelms the retina. In an inner polemic, sustained and suspended in a dispersed state through the basement, Anastasia Sosunova’s works begin from material artefacts that act as agents in collective responses to ‘injuries’ – economic and political breaking points that come as excessive events which form a negative space and partially reappear through traces they leave in cultural practices, codes and artefacts. (Plastic bottles of water filled at Orthodox service. Wood carvings of animals, Lithuanian grand dukes, Pensive Christs that proliferate as sculptures at roadside inn car parks and children’s playgrounds.) Tainstvo and Agents destabilise the cultural practices and codes of Christian Orthodoxy and folkloric symbolism – successfully co-opted into nationalist self-mythologies as ways of ordering the world – to open up the possibility of forms of co-existing and making, unbridled by the exclusions determined by some imagined past.

Insides turned outwards: the queasiness of exposure. Yet the mortar, plaster, aluminium – building materials commonly used as a base for structural soundness and the interior core of a building (meeting the exposed brick of the basement) – in Vytenis Burokas’ installation exist as the site for the transient and coreless character Crosswind, who splits into many while blowing and slouching from panel to panel. As if shifting between the polymorphous potential of queer identifications while working through unresolved inner frictions that frustrate attempts to become transparent to oneself, Crosswind-as-alter-ego is the shifting trace of an ongoing negotiation with the self.

At the heart of the question of visibility, ultimately, is the politics and ethics of subjectivation. Sheltered at the heart of the space demarcated by Burokas, Tarek Lakhrissi’s protagonist in Out of the Blue enacts a melancholia present within the emancipatory politics of today. Even the supposedly utopian future, where its goals are achieved and the marginalised are the ‘chosen ones’, is contaminated by the impasse of the current political imagination and its concomitant framework of representation. Brought onstage in the final scene – a marker of an entanglement between performance and representation – the protagonist’s melancholy is a restless impetus toward the possibility of a dignified future.

– Dina Akhmadeeva and Adomas Narkevičius

[1] Thomas Fuchs, ‘Body Memory and the Unconscious’, in Richard Gipps and Michael Lacewing (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Psychoanalysis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 461.

[2] See Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), p. 29; Okwui Enwezor, ‘Black Box’, in Documenta 11, Platform 5 (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2002), p. 45.

[3] Nicholas de Villiers, ‘Afterthoughts on Queer Opacity’, InVisible Culture, Issue 22, <https://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/afterthoughts-on-queer-opacity/#fnref-3843-39> [accessed 27 August 2021].

[4] ‘Lana Wachowski’s HRC Visibility Award Acceptance Speech (Transcript)’, The Hollywood Reporter, 2012 <https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/lana-wachowskis-hrc-visibility-award-382177/> [accessed 27 August 2021].

[5] Nicolas Evzonas, ‘Gender and “Race” Enigmatic Signifiers: How the Social Colonizes the Unconscious’, Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 40.8 (2020), p. 649.

[6] Lauren Berlant, ‘The Broken Circuit’, (interviewed by Sina Najafi, and David Serlin), 2008 <https://cabinetmagazine.org/issues/31/najafi_serlin_berlant.php> [accessed 28 August 2021].

Imprint

| Artist | Vytenis Burokas, Tarek Lakhrissi, Maria Loboda, Liv Preston, Anastasia Sosunova, Alexandra Sukhareva, Virgilijus Šonta |

| Exhibition | Avoidance |

| Place / venue | Centre for Contemporary Art FUTURA |

| Dates | 7 September - 14 November 2021 |

| Curated by | Dina Akhmadeeva and Adomas Narkevičius |

| Photos | Jan Kolský |

| Website | futuraprague.com/ |

| Index | Adomas Narkevičius Alexandra Sukhareva Anastasia Sosunova Dina Akhmadeeva Liv Preston Maria Loboda Tarek Lakhrissi Virgilijus Šonta Vytenis Burokas |