Piotr Policht: You’ve named your show at Bunkier Sztuki The Trouble With Value. What is so troublesome about the notion of value?

Kris Dittel: I presume the most obvious idea when one thinks of value is a monetary one, something that can be expressed in monetary terms. But if you look at art in general, in comparison to any product or thing, there has never been any specifically established criteria that allow the valuation of an artwork. You cannot connect it to the sole value of materials used, or to hours spent on making the work. There are various structures and ways how the value of an artwork is established, and the monetary aspect is only one. The narratives that are connected to historical objects, to the subjectivity of experience, to larger questions in society, are some examples. We wanted to problematize the question of what makes one thing more important than the other, what becomes important in art and what doesn’t. Historically and symbolically, these aspects are as important as monetary value and they are interconnected.

The show starts and ends with works that reveal the intangibility of value – Sława Harasymowicz telling the story of a family house, or Timm Ulrichs saying “Ich kann keine Kunst mehr sehen” (“I can’t see any more art!”), why did you choose to reference these particular works?

Krzysztof Siatka: These works are not the main points of the project, but still important ones. Sława Harasymowicz’s work focuses on construction and deconstruction of memory, topics deconstructed from our own culture, like a family house. Timm Ulrichs’s work is about the sense of sight, it’s impossible to see a work of art only, it’s impossible to use only a sense of sight. It’s a kind of neo-avant-garde monument of destruction of the old habits and old reason to establish the quality and value of an art object.

There is also a work by Rachel Carey in the show that explicitly shows the difference between evaluating consumer goods and works of art, a group of clay sculptures prized as regular objects, revealing the complicated structure of evaluation in arts.

K.S.: We wanted to make mechanisms of establishing value visible. Rachel Carey’s installation that you mentioned is one of the most important parts of the project because there are many levels on which you can interpret it. This works like an American estate sale, totally different from European culture. In Europe, when you want to liquidate some of your belongings you put it on eBay or trash it. But if someone in the America wants to liquidate their stuff, they do an estate or garage sale. So we gave the artist some things from the gallery we decided to liquidate. Rachel used those objects, like old furniture, or lightbulbs and so on, and created their artistic representations. So she raised a question: what is more valuable, the liquidated object or an art object based on it? And the third level of the work is a sale that was organized during the opening and the exhibition period, where anyone could buy the objects selected and put on sale by the artist.

The idea of avant-garde, not only neo-avant-garde, but the avant-garde as such, is deeply connected to the question of value.

K.D.: When it comes to those house liquidations in the US context, it oftentimes occurs in case of personal bankruptcy. After the 2008 financial crisis many people faced a situation when they had to sell everything they owned. During these liquidations people would enter someone’s personal space, where everything would be for sale. With Rachel we also talked a lot about labour, what it means to be employed, and what it means to work as an artist. Her sculptures are simple but time consuming to make, yet in this installation they are sold for a price based on their utility, as if it was for instance a paper weight. That creates a gap between value that we, as art insiders or art enthusiasts see in objects as these, and the value seen by someone who is coming outside of the art world, or someone who looks at them solely for their material or use value. In the previous iteration of this piece, the artist priced sculptures in collaboration with a professional liquidator. This time it was someone who is involved in selling antiques.

You are showing quite a lot of neo-avant-garde pieces, mail art and conceptual works. Do you find it to be a crucial point in art history when it comes to self-reflection on the notion of both symbolic and material value?

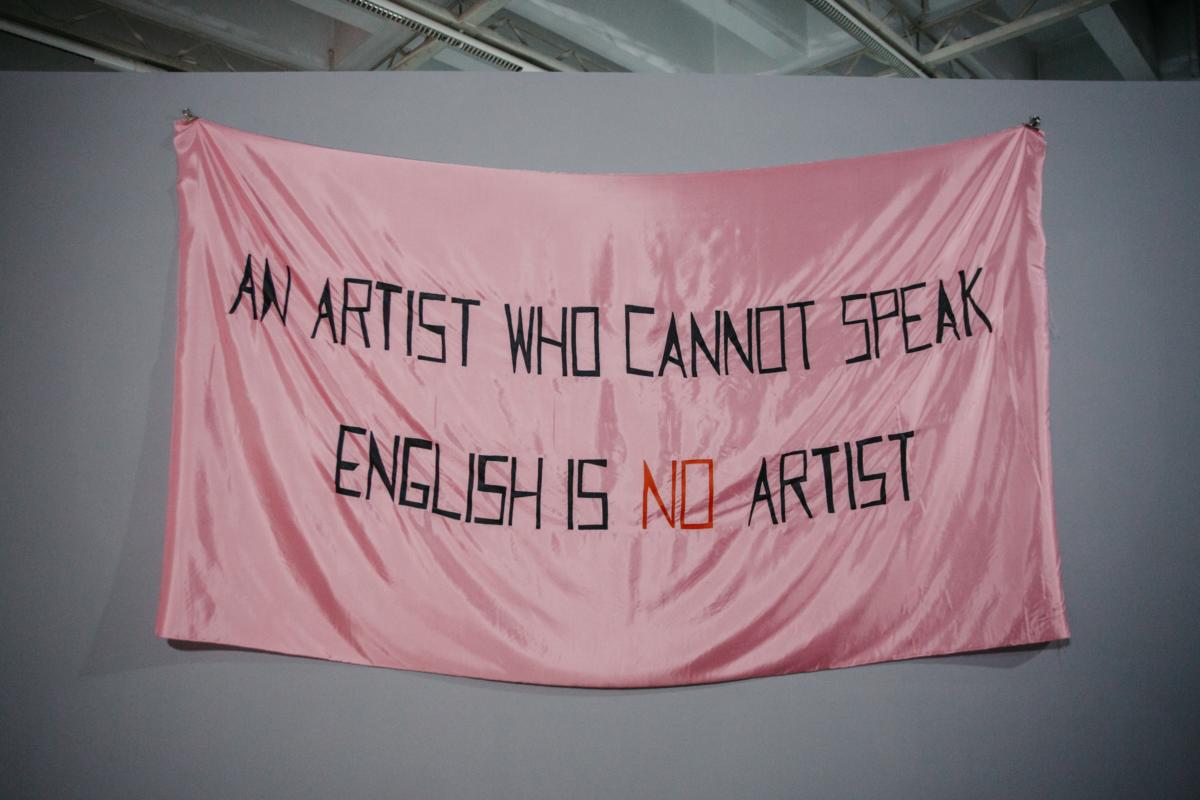

K.D.: A lot of conceptual artists challenged certain art formats, thinking about, for example, what a sculpture can be, what is the value of an idea, or that of a document. Like in Ewa Partum’s My Idea Is a Golden Idea, a work that in its original iteration operated simply on a conceptual level. What is interesting in the new iteration of this piece that she developed for the exhibition, is how this “idea” materialized in the form of a postcard that is disseminated during the exhibition and can be taken by the visitors. This is also an example how you can trace back a lot of developments when it comes to by now established formats in art, back to these neo-avant-garde, conceptual practices.

K.S.: I think the idea of avant-garde, not only neo-avant-garde, but the avant-garde as such, is also deeply connected to the question of value. How to change the existing system, how to change our awareness of the artwork, how to develop an art object. For me, the heritage of the 60s and 70s neo-avant-garde is one of the crucial points for the development of the late 20th century and beginning of the 21st century culture. I think each of the works we chose for the exhibition is kind of a post-conceptual creation that follows this awareness.

K.D.: In our discussion with Krzysztof we also wondered what it means to be avant-garde today? For instance when you think about the state of contemporary art, it oftentimes uses adjectives such as ”radical” and ”new,” but at the end of the day, are these developments really that radical, and are they really that new? Or did these ideas just became catchphrases to satisfy whims of the art market, or for the sake of our self-assurance of being progressive?

It’s impossible to negate the art market, but you can be very open about it and found your own ethics when it comes to interacting with it.

K.S.: The question what is avant-garde right now is still open, it’s not easy to make avant-garde art today.

But any idea of what it can actually be?

K.S.: We didn’t want to come to any conclusion, we wanted to invite the audience to think about the mechanism. If we gave an answer, the project would be stupid.

K.D.: Even in the booklet, instead of a curatorial text or description of artworks, we decided to follow the way we actually composed the exhibition. The exhibition can be read like one continuous conversation. We tried to react to each other’s ideas. Our strategy was to create an environment which will trigger ideas and questions, instead of just relying on what we had to say.

The art market is highly flexible and virtually anything, even pure “art as an idea” can be monetized in some ways. The whole system of establishing value is a set of communicating vessels. Both of you work at public institutions, in Netherlands and in Poland. Was your position in this system important for you when you worked on the show? Did you talk about how your experiences differ in that matter?

K.S.: I know, especially after this project, that a role of a curator is establishing value, making things visible. And the format of the exhibition is deeply connected to the system of establishing value. So we have the right to be the people negotiating symbolic value.

K.D.: Of course as a curator working in an institution you have the ability to influence symbolic or monetary value, this is something that we all should be constantly aware of. I’m working in a collaboration with Onomatopee, I’m representing it but I’m a freelancer, and this position also gives me a little bit more flexibility. To try to answer your question, it’s impossible to negate the art market, but you can be very open about it and found your own ethics when it comes to interacting with it. We also wanted to talk about the larger infrastructure of the art world. For example, the work by Fokus Grupa highlights how big of an impact platforms such as e-flux have in generating symbolic value.

Imprint

| Artist | Rachel Carey, Fokus Grupa, gerlach en koop, Sława Harasymowicz, Monique Hendriksen, Femke Herregraven, Gert Jan Kocken, „Kra Kra Intelligence” Cooperative, Sarah van Lamsweerde, Louise Lawler, Adrian Paci, Ewa Partum, Mladen Stilinović, Feliks Szyszko, Maciej Toporowicz, Timm Ulrichs |

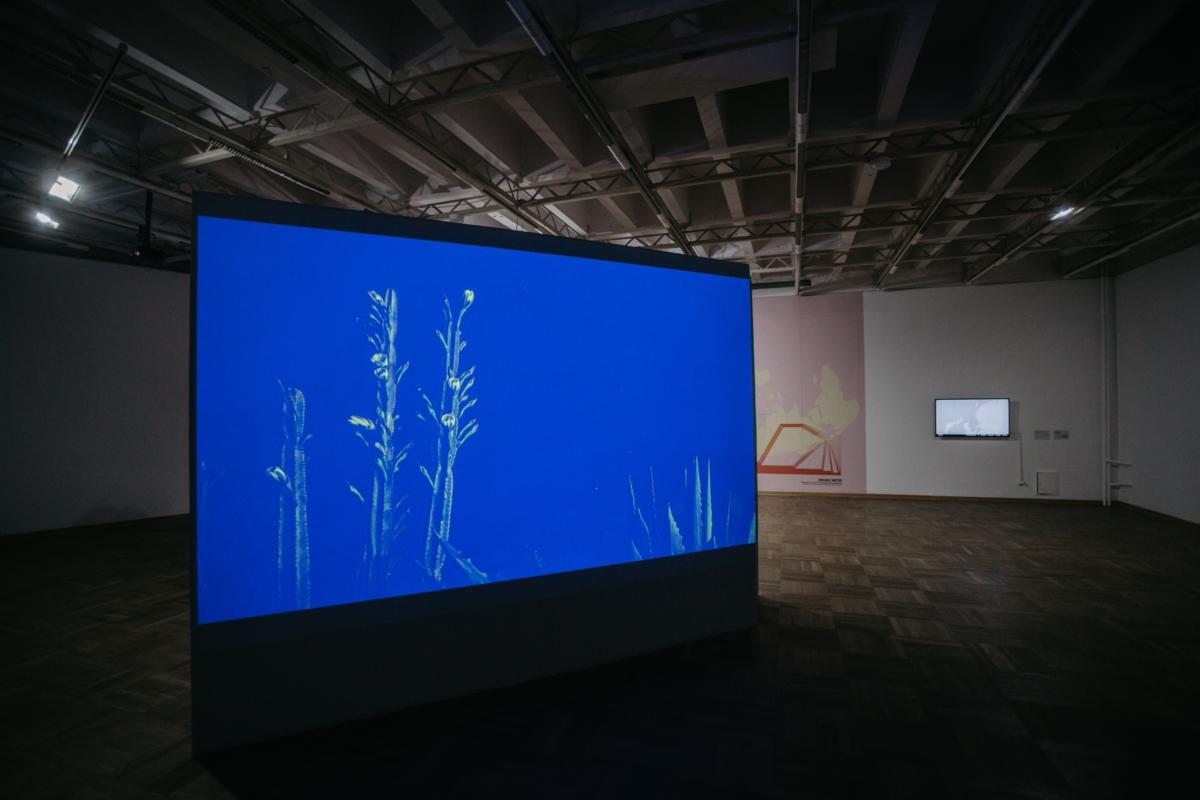

| Exhibition | The Trouble with Value |

| Place / venue | Bunkier Sztuki Gallery of Contemporary Art, Cracow |

| Dates | December 16, 2017 – March 18, 2018 |

| Curated by | Kris Dittel, Krzysztof Siatka |

| Photos | Studio FilmLOVE |

| Website | bunkier.art.pl/?lang=en |

| Index | „Kra Kra Intelligence” Cooperative Adrian Paci Ewa Partum Feliks Szyszko Femke Herregraven Fokus Grupa gerlach en koop Gert Jan Kocken Louise Lawler Maciej Toporowicz Mladen Stilinović Monique Hendriksen Rachel Carey Sarah van Lamsweerde Sława Harasymowicz Timm Ulrichs |