Anna Zvyagintseva is a Ukrainian artist, a member of the Hudrada curatorial group, a participant of the Ukrainian Pavilion “Hope!” of the 56th Venice Biennale and a winner of the Pinchuk Art Prize 2017. At the time when the interview was conducted she resided and worked in the Netherlands. Currently Zvyagintseva is based in Kyiv. When the full-scale invasion of the Russian army into Ukraine began, Anna was working in Maastricht.

I invited the artist to meet after attending her farewell talk at the Jan van Eyck Academie. Anna began her presentation with about seventy spectators. Silence enveloped the room as she displayed on the big screen the detailed pictures of the same hall we gathered in: concrete floor, curtain, walls. Anna was telling how on February 25, 2022, two days after the beginning of the full-scale invasion, she attended one of the events at the Academie and tried to hear at least some sound, or fix with her eyes at least some regularity in the things that surrounded her. She brought up the question on the screen “Will I be able to work? How can I do art now?”. And soon shared her answer: “I realized that the war aims to kill or paralyze all living beings. To continue artistic practice means to resist the war.”

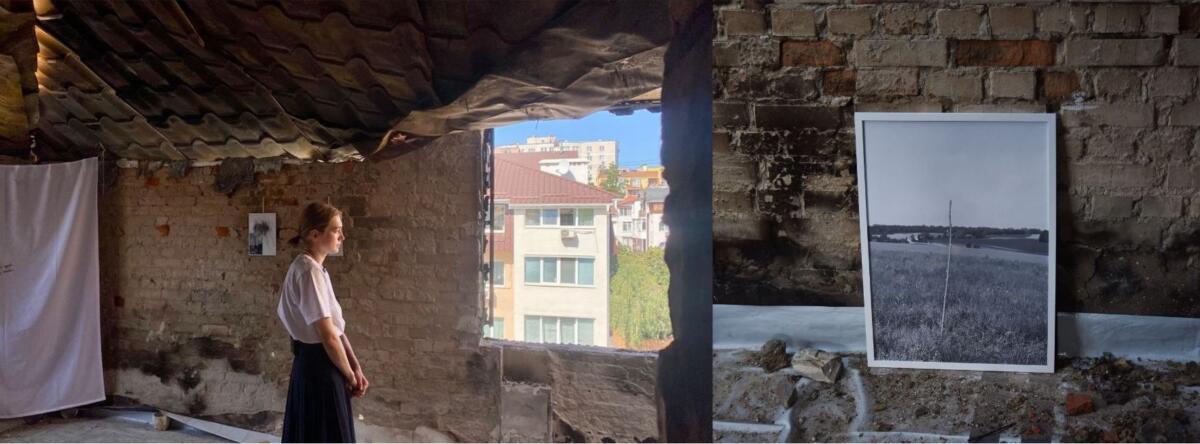

Our conversation took place later, in the artist’s studio. In the interview, certain illustrations are featured from Anna’s recent show at Liste Basel, where the artist was presented by The Naked Room gallery, the beating heart of Kyiv’s artistic community.

Anna, you come from a family of Ukrainian artists with a long history – your grandfather was an artist, and your parents were artists. Their lives are connected with Dnipro and Kyiv. What is the difference between the practices of your three generations?

The most obvious and biggest difference is that I’m using media they don’t work with. What we have in common is that I consider myself an artist who works with realism. My grandfather was engaged in landscape painting. My father and mother have more abstract works but all their themes are absolutely real. For me, painting and drawing is a saving moment, where I can reflect on all the events, and the war. My parents are in Ukraine. My Mom continues to draw what she has always been interested in–her family, everything that surrounds her, and my father, who was thinking about large-scale projects before the war, now makes sketches as well. He plunges into everyday life. I think it’s a great tribute to life. What is happening now is a fight for life.

I was very impressed by your work “My Father’s Sculpture”.

The image is based on small candy wrappers and pieces of foil which the father automatically folds into figurines when he thinks about something. It’s like doodling while on the phone. He leaves them everywhere–on tables and surfaces in the studio, or at home. I started collecting these wrappers after him. In 2013, I made my first personal exhibition, and put them in the window as a valuable work of art. So they look a bit like Scythian Gold. I always dreamed of enlarging one of them, and in 2021 it became possible: the small object became a four-meter copper sculpture. It is currently exhibited near Lviv in the sculpture project Park3020. I would also like to make real little gems, jewelry from them.

In the manifest, you write that your work is always autobiographical. At the same time, you dwell on things that remind us of the youth of our entire generation. About the years of uncertainty and the formation of Ukraine’s independence. The work “To Plant a Stick” is accompanied by the objects from your grandfather’s archive. How did this artwork get from Maastricht to the bombed-out apartment in Irpin?

My friend and contemporary art researcher Kateryna Yakovlenko decided to hold her first curatorial exhibition in her bombed apartment in Irpin, which was destroyed by the Russian army. The exhibition was called “Everyone is Afraid of the Baker but I am Thankful.” Katia wanted to talk about what happened to her home (her apartment and the country, to be specific) through the metaphors of plants and fragility. As far as my work goes, there could not be a better place, even though it sounds extremely painful. This work is dedicated to my grandfather. It began with the idea of how I see the memory of him. For me, it is always an image of endless meadows and fields, through which he walked with me and created drawings for future sketches. The sticks, which he cut before the hikes, always served as an attribute of our walks. Once I was looking through the archive of my grandfather’s sketches and came across a piece of paper with a line of his handwritten poem: “Like a tree without leaves, my soul stands in the fields.” And everything worked out like a puzzle, once I realized that I would plant a willow stick in the meadow, which would eventually sprout. In this work, dead and fallen tree branches are interpreted as the life-giving force that is created when they are left beyond our control. And finally, a stick is like a seed that will not germinate unless it is thrown into the ground.

How do you manage to produce art while being between peace and war?

When the war began, I could not perceive reality. There was a feeling of vacuum. Everything that was happening here became only the background, while all my thoughts and life were in Ukraine. It was extremely surreal. That’s when I realized that this paralyzed state was the very purpose of the war. If it is not possible to kill everyone, then the war aims at paralyzing as many people as possible. If I work, then through work and exhibition practice, I resist war. At first, it was annoying: how could it be so, when people live a peaceful life here, but we are bombed, killed and raped. As for now, I see a peaceful life here, and at some point I understand that yes – this is how it should be. And it should be like that for us.

What is the fate of your work “Sustainable Сostume for an Invader”? Is this a note on a contrast between the Dutch focus on the environment and our military reality?

I made this costume at Jan van Eyck in the spring of 2022, during the first months of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. We have all seen this incredible video, where a resident of Henichesk (Kherson region) went out on the street on February 24 and shouted at the armed occupiers: “Why the hell did you come to our land? Take the seeds, put it in your pocket! At least sunflowers will sprout when you lie here!”. What a powerful phrase!

At that time, it was the season of events dedicated to the environment at the Academy. Jan van Eyck has an awesome Future Materials Lab, which collects an archive of materials invented by artists and interdisciplinary researchers. These materials do not pollute the environment and are a sustainable alternative to traditional artistic production.

I began to think about how to develop this in my practice. That’s how I came up with this image of the invader, who lies down in the ground and plants grow out of his body… Sustainable Costume for the Invader is made of rabbit skin glue and seeds. I created a suit based on the first layer of military clothing, which is worn under the uniform. After all, no matter how much we would like to resort to mystical thinking and mystify them as demonic beings, they are people who do this, and it’s a terrible truth. I wanted to expose, to show the human essence.

There are many such paradoxes between the seemingly impossible concern for the environment during the war and real actions. For example, Ukrainian defenders, who were vegetarians before the war and consciously kept their practice of not eating meat, which is extremely difficult, when they went to the frontier.

As it turned out, the military apparatus was not ready for this, and the needs of vegans, fighting women are generally covered by volunteers. This shows how comprehensive the war is, different people are mobilized, with different experiences and beliefs, regardless of religion and identity. The issue of bread became globally critical again during the war. Of course, we knew that Ukraine was an important exporter of grain, but the scale of this export became clear only when Russia blocked Ukrainian ports. Thus, they put a number of countries at risk of starvation, such as Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Pakistan, and Tunisia.

Yes, by the way, we did not pay much attention to Russia’s role in the crises in Ethiopia and Eritrea, for example. The book “The Road to Asmara” by the Ukrainian writer Serhii Synhaivskyi, who served in Ethiopia as the Soviet army military translator in 1984-1987 during the war for the independence of Eritrea, tells about this. At that time, the presence of Soviet troops in Ethiopia was hardly covered in the media, and today few people remember it.

It’s true. And the bread problem itself became extremely acute with this war. Lesia Ostrovska in the text for the “Heart of the Earth” exhibition at the Mystetskyi Arsenal in Kyiv described the history of Ukraine as a place where people have always come for bread, since antiquity. Bread came to Greece from the Black Sea region, from the steppes near Kherson and Mykolaiv. I remember the crisis when there was so little money that we couldn’t afford food. That was in the early 1990s, in the first years of Ukraine’s independence. My work “Bread and Butter”, a silk screen print on a tablecloth, is about this experience. I remember some breakfast at home, when I was the only one who had butter on my bread. My parents ate plain bread. Luckily this was a brief period in our life. That’s how I could feel love and care, shared through food. A tablecloth is a fabric that reminds of family gatherings, care and sharing. I also find old tablecloths, and apply a simple pattern on them with a silk screen – the image of bread and butter.

During the Food Filmfestival, we organized a collective breakfast: my co-residents Suzanne Bernhardt and Anais Hazo baked bread and made butter, and we used these tablecloths to set the table. During that breakfast, people began to exchange stories. Everyone mentioned what they had heard in the news about the Russian blocking of Ukrainian grain. Many people in the Netherlands remember the famine during the occupation by Nazi Germany from their grandparents, as do we. Overall, the memory of the war is alive and the work of commemoration continues. Anne Wenzel is actively working on a monument commemorating the day the men from Rotterdam were taken as a labor force to Germany during the era of National Socialists.

What are you working on now?

I draw. This practice helps to pull myself together. I am currently making work for the exhibition Different Degrees of Freedom at Kunsthalle Bega, Timișoara. It is a huge curtain that has escaped from the window, got tangled in a knot and is falling in a plume. The drawings from my diary will be printed on this curtain. One of the images portrays a woman who tried to escape in an evacuation column near Zaporizhzhia. The column in which she was traveling was shot. The rescuers covered the woman’s body with a translucent cloth. It is both terrifying and eye-catching – like a white transparent veil or a bride’s veil. And the fabric always shows an image – a shape, or is soaked with blood, so that you can see a part of the body.

Following your advice, I revisited Johan Huizinga’s writing on war in “Homo Ludens.” Now, I’m curious to know what specifically drew you to this work.

I try to trace how Huizinga’s thought influenced the modern culture of the Netherlands, the artists with whom I now communicate. I found quite a lot of works that refer to his writing. After what we are going through, I am sure that the concepts of war and game cannot stand side by side.

Agreed. Huizinga views war as having rules, while the Russian army’s behavior lacks logic or rules. Perhaps this is one of the explanations why it is not always easy for us to come to an understanding with our European colleagues regarding the nature of this war.

I was deeply moved by Oleksandra Matviichuk’s speech. Oleksandra is the head of the Center for Civil Liberties, a Nobel Peace Prize-winning organization in 2022. She emphasized that our focus should be on seeking justice, not just peace. Even if peace is achieved, its longevity may be uncertain. True peace can only be attained after justice is served, with accountability for the guilty and the return of independent Ukrainian territories.