I entered the year 1968, in truth, I was completely passive laying on my back, like a two-month-old infant. Therefore I can not have any communicable memories. Yet it is emotional. When I was becoming an adult, everyone knew what it was like back then, but talking about it was only allowed with the best friends. The year 1968 is, for me and my generation, a symbol of social breakthrough and traumatic scar. We should probably already let it get healed, yet we are being pushed to touch it and to irritate it again and again. It seems that everything was concentrated in a few months, in several cuts: the liberalization of circumstances, its violent interruption, the subsequent social lethargy, and the disintegration. Socialism with a human face and occupation. Hope and hopelessness. Freedom and non-freedom. It was the year that predestined for the next twenty years, and at the same time the year that the future – in the sense of a free space of possibilities – ceased to exist for some time.

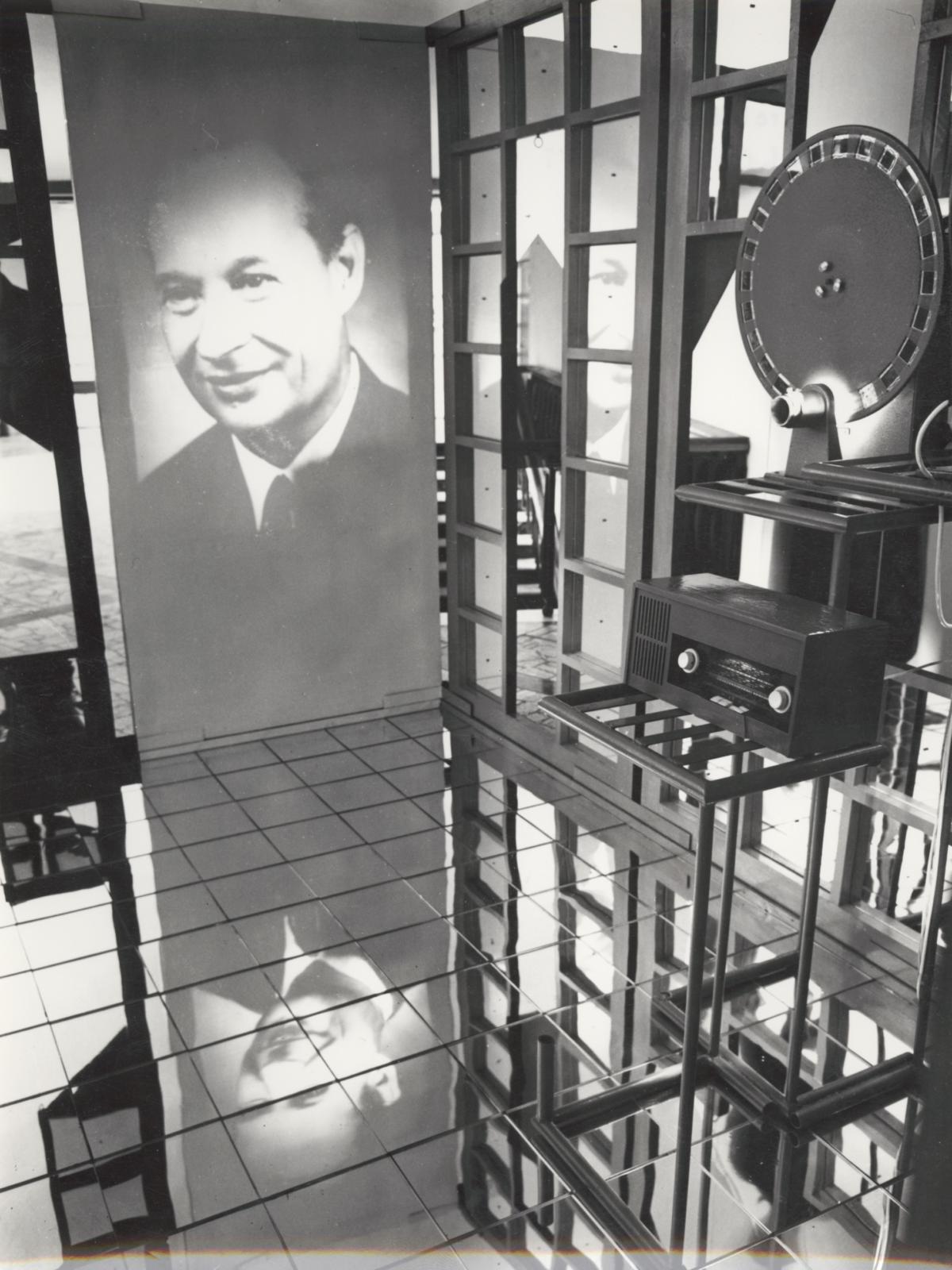

Similarly, the black and white arc between euphoric emancipation and freezing repression is, of course, a myth. The intervention of the Warsaw Pact troops, in August 1968, fits perfectly into the nationally popular narrative “what other people have done to us”, and they miss out what we have done to ourselves. This event became the prototype of the Great Fate Moment, which allowed us to relativize our own responsibility. The Czech perception of 1968 mostly ignores what was achieved, whether short or permanent. Characteristically, for us is similarly invisible result, for example, the federalization of Czechoslovakia. Yet, those few months of relative freedom – relative to what was before, and above all after, but also in absolute terms, are seen as a miracle. Or as a work of art. After all, at the Bratislava Danuvius exhibition in 1968, Stano Filko created one of his environments, the central point of which was the screening of some untrained pictures from the local press. In the eyes of an artist who called his work the Cathedral of Humanism, the internal political development was as rampant theme as the conquest of the cosmos.

In the field of culture, perhaps the most enduring and the most positive result of 1968 are the high quality books and magazines that were being successfully published. If we compare their content and, above all, the tremendous amount of copies to today, the present must appear as a real “Biafra of spirit”. The 1960s, and especially their end, are one of the golden ages of the Czech book culture and include the activation of the intellectual environment. Certainly, in later years it was not easy to get to these papers, but it was possible. What I learned about artistic avant-garde or post-war art in the 1980s and 1990s did not come from current sources, but it was largely mediated by what happened around us in 1968.

In the 1960s, the state’s ideological demands on art gradually declined. The art underground, which, if only partially, did not participate in any way in the state culture system, was minimal.

General overview of the year 1968 in the art of Czechoslovakia itself may seem somewhat flawed. There were no dramatic upheavals; on the institutional level, many things were going on like in the past. The Socialist state continued to provide generous funding and, as a result, managed the fine arts. In the 1960s, however, the state’s ideological demands on art gradually declined. The art underground, which, if only partially, did not participate in any way in the state culture system, was minimal. In 1968, many great works of art were created in Czechoslovakia, but not a dramatically higher number than in previous years. It is a moment of dispersed concentration, a massive breath, after which no adequate exhalation followed. Atmosphere of birth or transformation can evoke Eva Kmentová’s Human Egg, created in 1968. The author created a negative of her own body crumpled into a prenatal position surrounded by an egg-shaped form. Where and how far she stepped out of this shell that’s for every viewer to think for her- or himself.

Art and life began to get closer than before. In 1968, Zorka Ságlová created several sculptures on the topic of coincidence. She placed the rubber balls on the wooden surface and fixed them wherever they landed. She realized that coincidence, life (or whatever else we would like to call the central principle of these realizations) is aesthetized and frozen by its similar materialization. In August 1968, instead of static sculpture, she had the idea to simply throw the balls into the pond. However, it did not take place until April 1969 when Ságlová and her friends threw 37 coloured balls into the pond Bořín in Průhonice. They left them there to their fate and there remained only photographs after the event.

The basic ethos of 1968 was in the spirit of finding alternatives, discovering new levels of freedom, openness and experiment. In 1969, Jana Želibská realized the Kandarya – Mahadeva exhibition in the Václav Špála Gallery in Prague, culminating in her themes from the previous two years. Actually, only one topic; sex seen from the female perspective. Work lined with mysticism, humour, links to pop culture, art history, and kitsch. I do not know anything similar what would happen in the official Czechoslovak gallery in the next twenty years.

The centrifugal tendencies of Czechoslovak art in 1968 can perhaps be explained by the effort to catch up with the world for years of isolation and the need to orientate oneself in it. When we look at magazines and newspapers until August 1968, we can not overlook the frequent theme of “We and the World Outside”. The experience of the suddenly opened border barriers was heady, the paths “out” provoked to re-evaluate the experience so far, bringing inspiration and new ideas. “We and the World out” is also today one of the socially most important topics of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, but paradoxically in the opposite direction. Today, the Territory behind a virtual frontier works for many of us as a source of dangerous ideological divergence or even a physical threat.

Who, at least, could travel a bit fifty years ago, travelled abroad. For example, Alex Mlynárčik spent the turbulent May 1968 in Paris. He was moving in the center of the rebellion and photographed student challenges on the walls of the schools and state institutions. The question is to what extent his presence in the midst of the attempts to overthrow the current regime has influenced his next creation. The causes of French civil unrest may not have been easy to understand or to identify oneself with them. In May 1968, three Czechoslovak films were in the main competition of the Cannes Film Festival. When leftist directors in the lead with Jean-Luc Godard caused the early ending of the festival in the name of solidarity with the revolutionaries, the ambitious Czechs felt bitter about it. After all, they didn’t mind a competition for the bourgeois festival awards so much.

In May 1968, Petr Štembera, a student of the Faculty of Social Affairs and Journalism, also visited Paris. In his case, there was undoubtedly a transformative experience in relation to visual arts. At the exhibitions he had seen in Paris he realized he was not interested in painting, but in process art. As a tourist from the East, he walked around the city for ten days almost without food, which in his words led to the “discovery of his own body as such.” In the next decade, he will devote himself to private activities in the field of performance, which from the point of view of most of the population, as well as the Czech art communities, will be distant and incomprehensible from their concept of art.

The interest in Czechoslovakia, its destiny and its arts, then increased significantly after August 1968 and carried in a spirit of sympathy for the occupied state.

The year 1968 was a breakthrough, but at the same time poor for graspable artistic activities, even for Milan Knížák. Since mid-1967 he was on probation, he moved from Prague to Krásno in western Bohemia, where he gradually formed a free A-community, focused on an alternative way of life. In Krásno Knížák also experienced the entry of troops of the Warsaw Pact. In the aftermath of the invasion, in August 1968 he managed to obtain a visa to the United States, where he traveled in September. On the way, he was inprisoned in Vienna for a month for a fight with policemen. All he could do in there was the Action for my mind. Upon his arrival in New York, he made two more events, and then his activities became private.

Also the outside world was interested in our artists. Even before the August invasion, Jiří Kolář and Zdenek Sýkora were invited to Documenta 4. The interest in Czechoslovakia, its destiny and its arts, then increased significantly after August 1968 and carried in a spirit of sympathy for the occupied state. For example, the December issue of Opus International was devoted entirely to the art of Czechoslovakia. Orientate oneself in the situation after August 1968 did wasn’t always easy for foreigners. In March 1969, the radical left-wing film group of Dziga Vertov came to Prague, including director Jean-Luc Godard. The result of their stay was a documentary called Pravda (Truth), remarkable especially by its blindness to the feelings of the Czechoslovak population at that time. Godard complained about the state of leftist thinking, and it seems that he didn’t even notice that he is in the occupied country torn by the counter-revolution. More enlightened reaction to the occupation of August 1968 was the Czechoslovak Radio by the Hungarian Conceptual Artist Tamás St. Turby. The work has the form of a common brick with simply painted circles. The artist responded to the urban myth about the Czechoslovaks who provoked the occupiers by listening to the fake brick radios, which were confiscated by the confused soldiers in the tanks.

Similarly playful subversion lasted only for a few days. Attempts to reverse the development got a tragic dimension by the self-immolation of Jan Palach and others who followed him. The future began to fade. Július Koller moved towards the direction of conceptual art already before 1968 in Bratislava. At the same time, however, he continued to paint and develop his multifaceted activities. With the series of paintings of the Czechoslovak Republic he reflected the posterity events of 1968. However, the year 1969 was a breakthrough for him. At that time his question mark appeared for the first time as a universal symbol of doubt, uncertainty, unclear tomorrows.

With the arrival of the seventh decade, many Czechoslovak citizens were expecting the worst, the return of the Stalinist 1950s and massive imprisonments of political opponents. A similar development was also assumed by the secretly consecrated Catholic Bishop Felix Maria Davídek. Within the underground ecclesial community of Koinótés, he therefore consecrated also three women to the Roman Catholic priestesses in 1970. The reason for such a revolutionary step was not so much the belief that a similar office can be performed by men and women. Unorthodox Davídek, who, among other things, was interested in the happening and the Fluxus movement, wanted to build parallel church structures. He spent fourteen years in communist prisons himself and he wanted that, in the coming dark years, the Catholic priestesses were also able to act in women’s prisons. The darkiest forecasts were luckily not fulfilled, Czechoslovakia consolidated without a greater imprisonments. The names and fates of the two consecrated have stayed forever unknown.

Undoubted loss for Czechoslovak society and culture was the emigration wave, which culminated in 1968-1970 and to a lesser extent continued until 1989. Traveling abroad was limited. The artistic life of Czechoslovakia was radically reorganized after 1970. The original Czechoslovak Fine Artists Union, which brought together several thousand artists, was revoked as ideologically unreliable. Instead, a strict selective organization was established, which had only a few dozen in the first years, later hundreds of members. Obtaining state commissions in the field of art was difficult for untested artists in the Czech Republic in the 1970s, perhaps somewhat easier in Slovakia. To publicly exhibit was problematic, one of the ways to bypass the selection boards was to organize exhibitions in small clubs or non-artistic organizations. Magazines were not worth anything. After 1980, however, the ideological control was lowered again and a number of condemned artists agreed on the rules of the game. Gallery purchases, exhibitions, and commissions also went to those who had been unreliable for the past decades. The new Czechoslovak Fine Artists Union had again 4,000 members in 1987. People around the arts who totally refused to participate in the official artistic life were a few dozen.

Undoubted loss for Czechoslovak society and culture was the emigration wave, which culminated in 1968-1970 and to a lesser extent continued until 1989. Traveling abroad was limited. The artistic life of Czechoslovakia was radically reorganized after 1970.

The contemporary young generation in the Czech Republic and Slovakia already has no emotional relationship with 1968. It does not follow up on its possible social or artistic links. But maybe there might be a useful lesson here. The first half of 1968 and its hopes in the Czechoslovak context strongly contrasted with what had come in the middle of the second. The next two decades were terrible in most respects. But it was not endless. Even though I do not want to compare these days and fifty-year-old history, it could be at the core of a lesson for today’s gloomy mood. We should not consider the situation in 2018 as an unchangeable state, at least think and talk about what is wrong, what else to do, having your program as well as a method how to fulfil it. The history message is clear: we do not choose the time we live in. But it is up to us what we will do with our time. And we know almost with certainty that in fifty years somebody will be interested in why and for what we have decided today.

Imprint

| Index | Tomáš Pospiszyl |