The World Does not Believe in Tears: Longing and Trauma in the Art of Białystok and Podlasie

The exhibition “The World Does not Believe in Tears” presents works by artists born in the 1980s and 1990s in the titular region, including artworks from Collection II of the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok. Participants of the show had left their hometowns in search of artistic education, in most cases never to return. This will be the first such exposition of art by representatives of the aforesaid generation hailing from Podlasie[1] and exploring assorted media. The exhibition title has been taken from a piece by legendary Białystok bard and author of revelry and street songs, Janusz Laskowski. His 1995 tune[2] alludes to suffering as a universal human experience, and a sense of helplessness in the face of time and fate. On the one hand, “The World Does not Believe in Tears” can be interpreted as the flip side of enthusiastic narratives referencing system transformation, on the other – as a voice of existential truth non-privileged and discriminated individuals and social groups can identify with. Such perspective forms the centreline of the show, wherein personal experience, memories and family stories have been flanked by tropes referencing collective trauma, oppression, and the region’s convoluted identity.

The video clip accompanying the song The World Does not Believe in Tears shows Laskowski driving a Polonez across a Białystok that is no more, captured immediately prior to transformative modernisation. He visits the residential quarter of Bojary, still wooden, unblemished by invasive development; the bazaar on Kawaleryjska Street, full of life; and the no longer existent concrete amphitheatre, its exact spot now occupied by the modern Podlasie Opera and Philharmonic building. He ends his sentimental journey in a circus arena, in a potential suggestion that life is a stage where everyone has his or her role to play, be it mournful, dangerous or comical. The bard’s progress is ever so often interrupted with black-and-white images of suffering: children crying, a funeral, war. Immersed in melancholy, Białystok of the 1990s is thus set to the context of global events, becoming one of the many locations on the map of violence and sorrow.

Inspiration with Laskowski’s piece could well tie in with the nostalgic nineties’ wave trend expressed in attempts to romanticise the visual culture of the period in popular culture and online. Yet the exhibition “The World Does not Believe in Tears” shows that longing, while potentially pleasurable, is problematic – it tends to sugarcoat the distant past, any thorny phenomena or themes vanishing from the field of vision. These may include childhood memories we have no wish to remember, or – on the macroscale – the unwelcome legacy of transformation. Given the aforesaid context, Skup łez (Tears Collection Point) by Alicja Rogalska, originally from Śniadowo near Łomża, and Łukasz Surowiec, is a pioneer realisation, recognising the viewpoint of social costs and adverse change outcomes while telling a poetic story of affective work associated with experiencing economic oppression. The project was actually delivered in Lublin, another peripheral city along Poland’s eastern border. The artists opened a venue where for a few days people would be paid in cash for tears cried on site, the going rate one hundred zlotys for three millilitres. The place was located in a district brimming with pawnshops, commission stores and fast cash loan offices, all very popular in Podlasie as well, and – in a simile to aforesaid “financial services” –designed as a source of fast cash. The artists’ proposition was received extraordinarily well by local residents, swiftly gaining considerable media coverage, which goes to show what a universal and uniting experience crying can be. It offered a promise of capitalising hurt, and getting rich on personal suffering and emotions experienced. How rich would we be if paid for our tears in real life as well as in art?

Kuba Dąbrowski explored other emotions – rage and irritation – in his photograph series Co cię denerwuje? (What Gets on Your Nerves?)[3]. Developed in street survey formula, it shows regular people encountered in the street. When asked the title question, they pinpoint personal troubles as well as political and economic events.

Had the Tears Collection Point opened in Białystok, its clientele could have included Danuta and Władysław Kopciewski, former workers of the “Fasty” factory, and Rafał Zajko’s grandparents. In the video Nić (Thread), grandma Danuta’s hands are packaging shoelaces, using an appliance constructed by her husband. Thread is a record of piecework performed by retired workers after “Fasty” had shut down. Zajko’s artistic interests were ultimately moulded by the relationship with his grandparents who had brought him up, and frequent childhood visits to the local factory. In his works, objects shown at the exhibition included, the artist reflects on the coexistence of man and machine, juxtaposing the uniqueness of touch, tenderness and effort of manual work with the coldness of machinery and standardised manufacturing. Family member stories associated with labour and migration are referenced by other artists as well. In her series of works Kurz ma słodki smak (Dust Tastes Sweet), Iza Rogucka recalls her childhood through the aroma of powders used in ice-cream and waffle production, and the intricacy of machines her father built. Owing to economic migration to the US, her parents could open one of the first soft ice-cream parlours in Białystok at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s. As buying a ready-made machine was not an option in those days, the artist’s father built all his ice-cream- and waffle-making appliances himself. Rogucka re-enacts them in her work Tajemnicze złote maszyny (Mysterious Golden Machines) as models in golden paper, the stuff of childhood fun and games, turning them into family treasures seen through a child’s eyes. Grażyna Monika Olszewska’s parents sought work across the water as well, her mother working as a cleaner of luxury residences in suburban Chicago. Olszewska tells the story in her computer game Wealthy Woman – a virtual simulation of the American dream wherein the artist archives her own mother’s photographs, memories and desires.

Childhood memories – in case of artists referenced herein usually coinciding with years of intense social and mental transformations stimulated by the free market, the euphoria of new opportunities and aspirations, and the omnipresent paradigm of social advancement – are a major trope of the show. Karol Radziszewski explores the process of decrypting childhood and teenage memories, using his work 1989 to transfer his own youthful drawings onto a large-scale wall painting, and choosing transformation motifs playing out in fantastical rather than political space, all produced by a young imagination. Young Karol’s sketchbook was populated with hybrid creatures, characters of fable and myth. Princesses and a syren canine are accompanied by a disturbing image of a crucified male – the likeness of sadism and suffering, appearing in religious communities through socialisation efforts. While Catholic ideology occasionally becomes a burden for queer persons, Radziszewski tries disenchanting it, recognising it as no more than a phenomenon which had moulded him. The video Chwalcie łąki umajone (Praise May Meadows in Floral Glory) shows him singing the titular Marian song with his grandmother. Przemek Pyszczek’s Playground Structures works effervesce with joyous colours as well. Born in Białystok on the Piast housing estate, the artist emigrated to Canada with his parents at the age of two. In his works, he references the colours and shapes of socialist block of flats projects, paying particular attention to playgrounds that surround them, thus recreating a childhood scenery he had not had the opportunity of experiencing himself. Yet Pyszczek’s metal playground structures are ever so slightly modified, changing shape, losing their original purpose. Ania, Emilka and Nico – today members of the Żurnal Zin collective – first met at one of these playgrounds. The group shared a number of dreams, one of them to leave Białystok, which they managed after having taken secondary school final exams. Members of the collective were accepted by a university in London, where they now live together as a queer family, publishing a fashion zine. Żurnal Zin are showing Wyleciałyśmy wczoraj (We Left Yesterday), a bespoke project created for the exhibition, set in the phantom Białystok-Krywlany airport. The purpose and function of Krywlany[4] kept changing over the decades – the place was a racetrack for a time, a drift park, the venue where the local residents met the pope, a used car sales lot, and seat of the local aeroclub. An airport is to be developed on the site, an unfulfilled decades-old promise of iconic modernisation for the city and region[5]. Just like in the biographies of many individuals born in the region yet choosing to spend their adult lives elsewhere, the group’s video performance shows Białystok as something akin to a runway, a place you depart from to journey on, or even one you escape forever.

Why is it so difficult to go back? Śnił mi się rodzinny dom (I Dreamed of my Childhood Home) is another of Janusz Laskowski’s songs echoing across the exhibition[6]. Away from his birthplace, the storyteller persists in revisiting it in thoughts. While he reminisces about the home he is missing – safe, filled with warmth and affection – the home of his dreams remains just that: a vision in a dream. At the exhibition, sentimental retreats extend beyond Białystok and the 1990s to include Podlasie as a region forceful in defining personal identity. Works opening the exhibition: Iza Rogucka’s Każdy ma swój płatek śniegu (Everyone Has Their Snowflake), Eliza Proszczuk’s Pasiak (Striped Rug), Milena Korolczuk’s Białystość (Białystokness)[7] and Adrianna Konopka’s Żubrołak (Werebison) allude to the symbols and phenomena of Podlasie: folk art, architecture, religiousness and nature. Werebison shows a female nude, hair flying, galloping across a field, straddling a European bison. The bison is shown in the company of a falcon and lynx, both animals forming part of the Magical Podlasie imaginarium, an exoticised land of wondrous nature and serene rural landscapes. Konopka’s character seems to be struggling in riding the bison, as if attempting to take control of the tranquil narrative of the region and its overwhelming charm.[8] Łukasz Radziszewski references the postcard image of Podlasie and its accompanying myths in his practice as well. In semblance of Janusz Laskowski and his video clip, he invites his audience to take a sentimental ride across the neighbourhood and plunge into Podlasie’s vibe.

Podlasie’s magical aura of a region of extraordinary nature, multicultural heritage and rural culture builds a remarkably powerful image stereotype, the narrative frequently employed to promote the region. The other extreme is one of an image of a conservative backwater commanded by aggressive nationalists, popularised i.a. by Marcin Kącki’s book Biała siła, czarna pamięć (White Power, Black Memory) and replicated in national media. The discord between the two extremes disallows any nuanced thought or comment about Podlasie or Białystok, as avoiding the trap of fetishisation and exoticisation on the one hand and contempt and fear on the other is well-nigh impossible. The imagery of such powerful features reduce Podlasie either to a natural paradise one escapes, or a political reality steeped in fear, making it difficult to openly declare progressive beliefs. The exhibition explores symbols defining the region’s identity in an attempt at rediscovering them, revealing the ambiguous fabric of meanings the stories of Podlasie are woven of.

The forest is one such symbol. The forests of Podlasie enrapture with beauty while keeping their eerie secrets out of sight. One moment, they are a natural habitat offering respite and shelter, turning into a place of crime, battle and suffering the next. Paweł Matyszewski showcases that ambivalence, the natural world in his paintings a terrifying abyss breeding subtle ornamental patterns. In 2.04.2022, a story by Adelina Cimochowicz, weather becomes a lethal element, the artist referencing a phone conversation between two persons, one of whom requiring assistance in a life-threatening situation, the other trying to help remotely. The event may be a recollection of the humanitarian crisis on Poland’s border with Belarus, and the drama of people helpless in the face of forces of nature and geopolitical turmoil.

Over the ages, tress have been silent witnesses to multiple events: warfare, murder, pogroms. Timber becomes a remembrance carrier in Błażej Rusin’s series of works Drewno haptyczne (Haptic Timber). The artist treats wooden panels with acid and concrete, grinding traces, affecting the texture of the material, outcomes of the process palpable to touch. The cycle is an abstract study of the Dojlidy[9] Ponds landscape, and Rusin’s final work before he moved away from Białystok. Jan Szewczyk presents his Wykrot (Windfall) – a 3D model of a felled fir, including the entire root system ripped out of the soil. Windfalls are the outcome of ecosystem transformation caused by climate change, a trap for ungulates – and a shelter for people hiding in the forest. The work is the model of the largest windfall Szewczyk managed to find in the Białowieża Forest.

The windfall can also be interpreted as a symbol of identity uprooting following the decision to leave one’s birthplace. Thus rendered roots are shown in Adrianna Konopka’s Dziennik rysunkowy (Sketched Diary), a work in progress since 2017, wherein the artist record her emotional states. The series of works in ink, acrylic paint and felt-tip pens on food wrapping paper shows dismembered bodies, scars, bodily fluids arranged in assorted configurations and sprouting roots. Root systems have also been shown by Eliza Proszczuk, who enhanced a double warp fabric by a weaver from Janów Karolina Radulska with embroidered roots (Wątek podwójny / Weaving Two Threads).

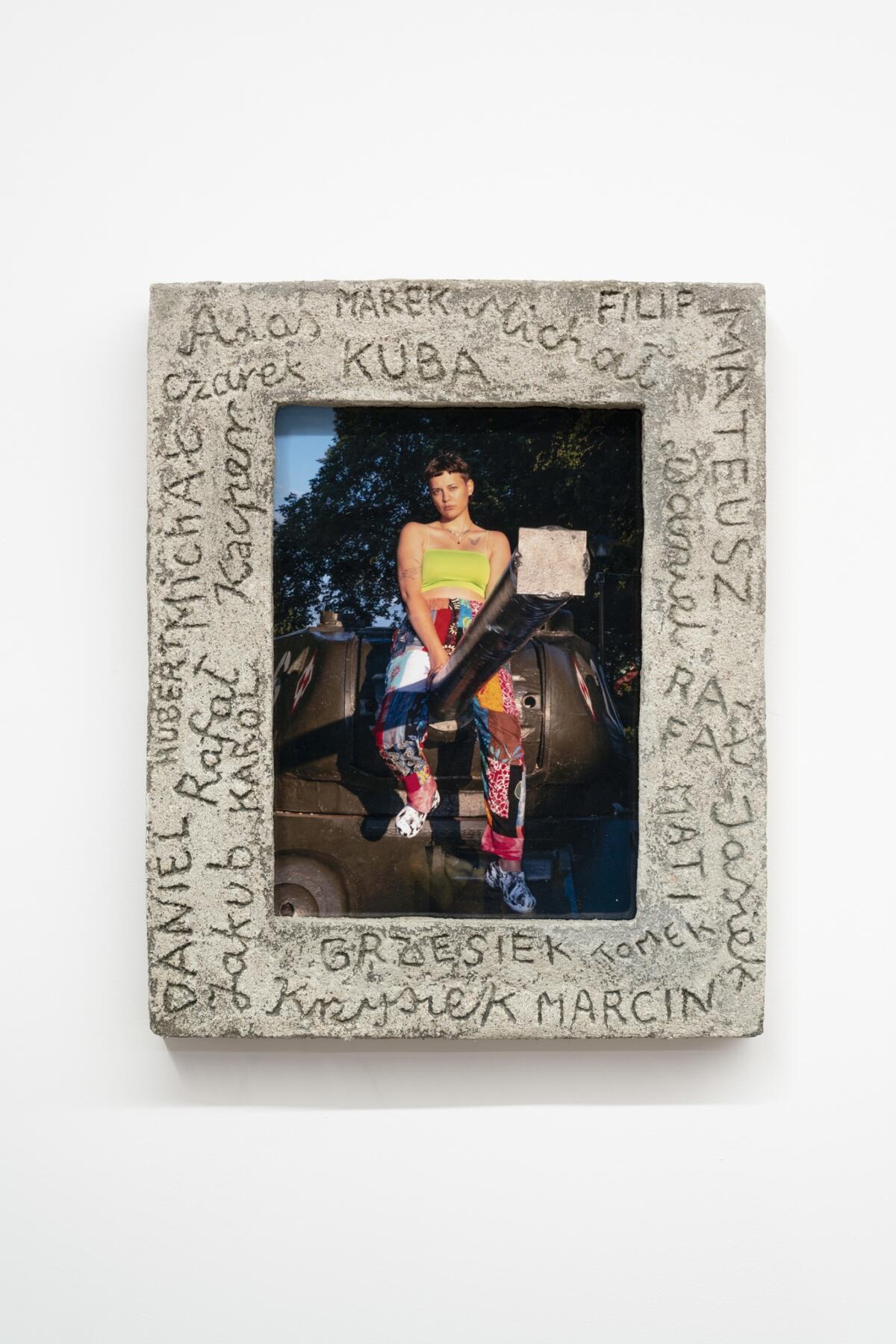

The last room has been set aside for herstories associated with the region, and women’s work. Artefacts include i.a. jars of preserves made by Adelina Cimochowicz’s mother. This is a new rendering of Spiżarnia (Pantry), a project the artist had launched in 2019, archetypal labels replaced with a fragmented epic poem, notes on a sense of belonging, crisis experiences, care and health. Originally from Narewka, Belarusian poet and painter Katarzyna Sienkiewicz presents encaustic paintings in combination with fabrics made by her ancestresses and next of kin. The artist references the symbolism of ornamentation depicted in traditional Belarusian weaving. An untitled work (bedspread, self) features the symbol of a rose accompanying wedding ceremonies. Its rosy patterns concealing the artist’s schematic self-portrait, the titular bedspread can be interpreted as a straitjacket of traditional norms and customs distorting one’s own image and identity. Aleksandra Czerniawska’s Wesele (Wedding) also references the social and performative dimension of wedding rites.[10] In the foreground, the bride and groom surrounded by family members; in the background, renderings of individual stages of the ceremony: the sacrament at the orthodox church, the abundantly laid table, the dancing. Ostensibly a social genre scene, it conveys an upsetting mood of mandatory heterosexuality and oppressive cultural models, wherein being a wife and caretaker is one of the roles imposed upon women. Martyna Modzelewska, originally from Grajewo, confronts patriarchate as well in her photographic self-portrait Park z czołgami (Park with Tanks). The photograph shows the artist seated upon a tank in the titular park on Wojska Polskiego Street in Grajewo. To be precise, she is straddling the tank gun, in emulation of boys who would pose for similar photographs and upload them to early Polish social networking media, such as www.fotka.pl or www.naszaklasa.pl. In re-enacting the gesture, the artist symbolically recaptures agency in an attempt at compensating the burden of growing up in a culture of normalised sexism. Paweł Grześ’s film Palimpsest is a yet another representation of female power, Ewa Hołuszko the lead protagonist, a Białystok-born campaigner for transgender persons’ rights today, accomplished “Solidarity” movement activist in the past. In Palimpsest, she talks i.a. about her religiousness and ties to the region where she remains largely obscure. In 2019, Hołuszko walked in the first row of the traumatic 1st Equality March in Białystok. The activist’s biography is an interweave of the complete spectrum of past political, cultural and social phenomena over several dozen years.

In closing, let me share my own story involving Podlasie, the region I grew up in. In early 2021, I moved back from Poznań to my family home in Kuźnica, a town on the Polish-Belarusian border. Several months later, I was thrown out by my father, homophobe and religious fanatic. Shortly after I had been forced to bid my family home farewell, uprooted and transplanted, the humanitarian crisis broke out on Poland’s border with Belarus. Due to its location, my parents’ house became part of the state of emergency zone, accounts of pushbacks and deaths mentioning names of locations from my municipality, villages I know where I used to ride my bike and run as a teenager. While many of my friends and acquaintances joined the effort of providing direct help to those in need, I found myself unable to enter the woods, though I was part of the few legally allowed to remain in the zone. At the same time, I found it difficult to watch developments in my home I had lost, in a neighbourhood I am emotionally attached to and care very deeply about. Ultimately, I repressed any sense of responsibility for what was going on down there, choosing to save myself from the dark abyss of the cross-border area. I am sharing my story to emphasise how difficult it is to affirm Podlasie or the local identity; to appreciate and elevate this region of poverty and difficult families, of a history gouged and never healed, wherein unprocessed traumas of the past are continuously expanded to include one contemporary tragedy after another. Many of my generation shared that perspective, including artists whose works are shown at the exhibition.

[1]Notably, the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok organised two other exhibitions similar in purpose and style: “przez Białystok” (via Białystok, 1997), a show of works by an earlier generation of authors originally from Białystok and the region: Andrzej Bąkowski, Witosław Czerwonka, Mirosław Filonik, Konrad Kuzyszyn, Wojciech Łazarczyk, Agata Michowska, Małgorzata Niedzielko and Zbigniew Oksiuta, curated by Monika Szewczyk; and “Protoplazma” (Protoplasm, 2010), a show of works by students and graduates (from Podlasie) of the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznań: Paweł Dziemian, Natalia Fiedorczuk, Marcin Gwiazdowski, Justyna Kisielewska, Milena Korolczuk, Marta Mariańska, Paweł Matyszewski, Zofia Nierodzińska, Luks Piekut and Jan Szewczyk, curated by Iza Tarasewicz. (All footnotes by language editor of the Polish version Ewa Borowska).

[2]Lyrics by Ryszard Ulicki, music by Jan Adam Laskowski, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ndSCJsyKf6s.

[3]Work from Collection II of the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok.

[4] Krywlany – south-eastern part of Białystok, formerly one of the oldest local villages. Works to build the Białystok-Krywlany airfield began on site in the 1930s, the investment completed as a makeshift solution in 1937 and modified in 1939, on the brink of World War II. Polish armed forces were based here briefly during the war; they were replaced with Soviet, then German units, all continually developing local infrastructure. When retreating in July 1944, Germans blew the airfield up. Once Białystok had been liberated (1944), Soviet air force troops returned and were stationed on-site. The Białystok Aeroclub was registered in May 1946. For more on the history of Krywlany, see: http://epbk.pl/oferta/aeroklub/historia.html and https://poranny.pl/lotnisko-krywlany-tu-hitlerowcy-szkolili-pilotow/ar/5494968.

[5]In early 2015, the mayor of Białystok and Białystok Aeroclub authorities signed a letter of intent, pursuant to which efforts began to transform the airfield from a sports facility into a civilian airport. Yet nearly 15,000 trees would have to be felled in the local Solnicki Forest in order for the full runway length to be used, State Forests and social organisations protesting the decision. In June 2021, the Regional Administrative Court in Białystok annulled felling approval decisions (editor’s comment), duly blocking airport development.

[6]Lyrics by Ryszard Ulicki, music by Jan Adam Laskowski, listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rMtQ-SLuNpc.

[7]Work in Collection II of the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok.

[8] Romantic or erotic images of female nudes riding European bison are a frequent motif in local “souvenir art” – cheap paintings and/or drawings sold to tourists at marketplace stalls.

[9]Dojlidy – formerly a village, part of Białystok today, with a complex of 19 Dojlidy Ponds.

[10] Work in Collection II of the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok.

Imprint

| Artist | Adelina Cimochowicz, Aleksandra Czerniawska*, Kuba Dąbrowski*, Paweł Grześ, Adrianna Konopka, Milena Korolczuk*, Paweł Matyszewski, Martyna Modzelewska, Grażyna Monika Olszewska, Przemek Pyszczek, Eliza Proszczuk, Karol Radziszewski, Łukasz Radziszewski, Alicja Rogalska & Łukasz Surowiec, Iza Rogucka, Błażej Rusin, Paweł Sakowicz, Katarzyna Sienkiewicz, Jan Szewczyk, Iza Tarasewicz*, Rafał Zajko, Żurnal Zin |

| Exhibition | The World Does not Believe in Tears |

| Place / venue | Galeria Arsenał in Białystok |

| Dates | 26.08 - 06.10.2022 |

| Curated by | Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew |

| Photos | Tytus Szabelski |

| Index | Adelina Cimochowicz Adrianna Konopka Aleksandra Czerniawska Alicja Rogalska & Łukasz Surowiec Błażej Rusin Eliza Proszczuk Galeria Arsenał in Białystok Grażyna Monika Olszewska Iza Rogucka Iza Tarasewicz Jan Szewczyk Karol Radziszewski Katarzyna Sienkiewicz Kuba Dąbrowski Łukasz Radziszewski Martyna Modzelewska Milena Korolczuk Paweł Grześ Paweł Matyszewski Paweł Sakowicz Przemek Pyszczek Rafał Zajko Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew Tytus Szabelski Żurnal Zin |