Vasyl Lyakh sat in the backseat of the car as we drove to Lublin. In the mirror I could see the colorful hair of Anita Nemet, curator of the exhibition Near/Far and our unofficially designated trip translator. To kill time, we talked about the exhibition that they were then preparing in Warsaw, about who does and who doesn’t get drafted into the Ukrainian army and whether artists are allowed to leave the country. At one point Nemet, who emigrated to Madeira because of the war, interrupted, saying: “How I miss this landscape.” I took my eyes off the road to look around. All around were empty fields sprinkled with snow, the atmosphere was gray, foreboding.

Not long after, we arrived at Galeria Labyrint, where the exhibition I Dreamt of the Beasts was closing. One of the works included a row of seats that looked like they were torn out of an old movie theater. As we sat, the screen displayed a video that resembled a simulation of the end of the world, or a scene from the series The Last of Us. Only it wasn’t a game or a series, but a video shot in Azovstal, by Dmytro “Orest” Kozatsky, one of the soldiers who was defending the steel plant which became a de facto shelter for many remaining citizens of Mariupol. “That’s where I’m from,” Vasyl said.

Lyakh brought his rolled-up paintings to Poland from Lviv, where he has been temporarily living since he left Mariupol. For the exhibition Near/Far at Galeria Promocjyna, it was decided that instead of securing them on stretchers, they would be hung without these frames, like fabric on the walls or free-floating in the space. If I didn’t know about how they arrived in Warsaw, I would have thought this decision was a curatorial gimmick. Another trendy exhibition of figurative painting, easy to read, uncomplicated in its message. What sets Lyakh apart however is the fact that despite ticking all of these aforementioned boxes, he manages to embed his paintings with meaning that many other artists continue to seek, unsuccessfully.

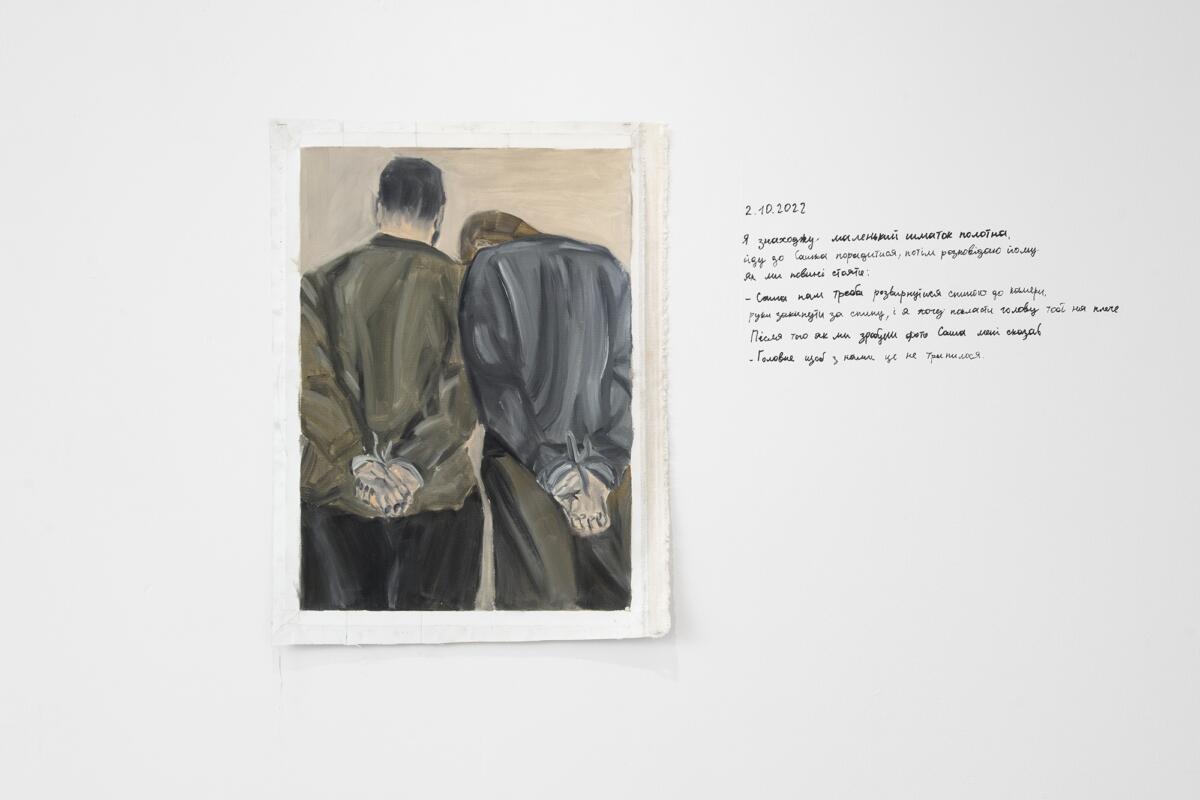

One example is described by the curator as “survivor syndrome.” What is in the mind of a survivor? First and foremost, the deaths of all those who could not be saved. The only triptych in the exhibition (five more paintings and two videos are presented as well) is composed of three strips of canvas. The painting surface is narrow, the frames are cramped, there is room for only what is necessary. On the left is a shovel stuck in the dirt, on the right a draped cloth, threaded with string in the middle, like a sack in which we can only guess, a body has been laid. The middle piece, a long, horizontal band of canvas, leaves nothing to the imagination. A prostrate body lies haphazardly on the ground with his hands tied behind his back and a sheet over his head, it is a sharp image of death.*

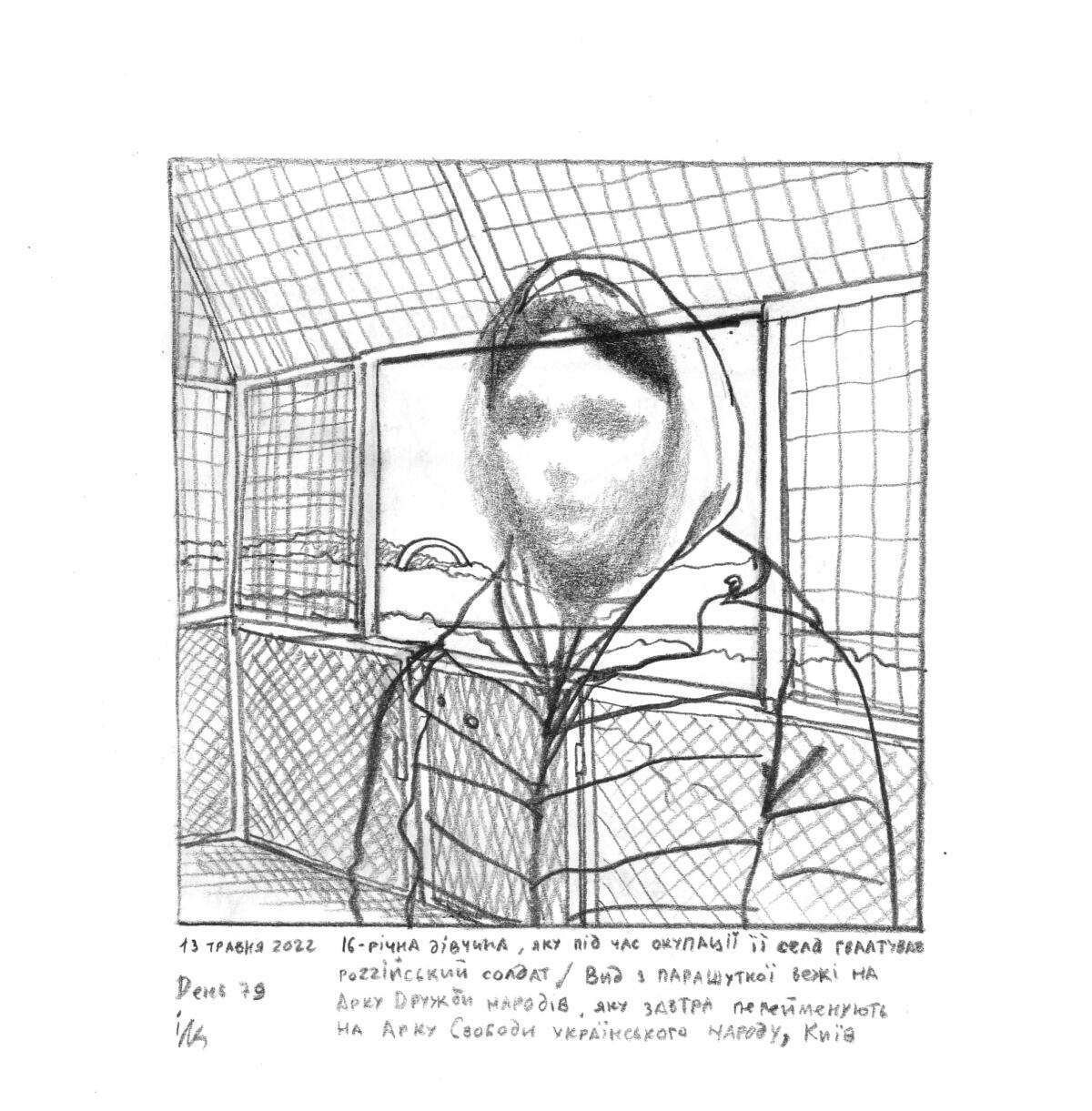

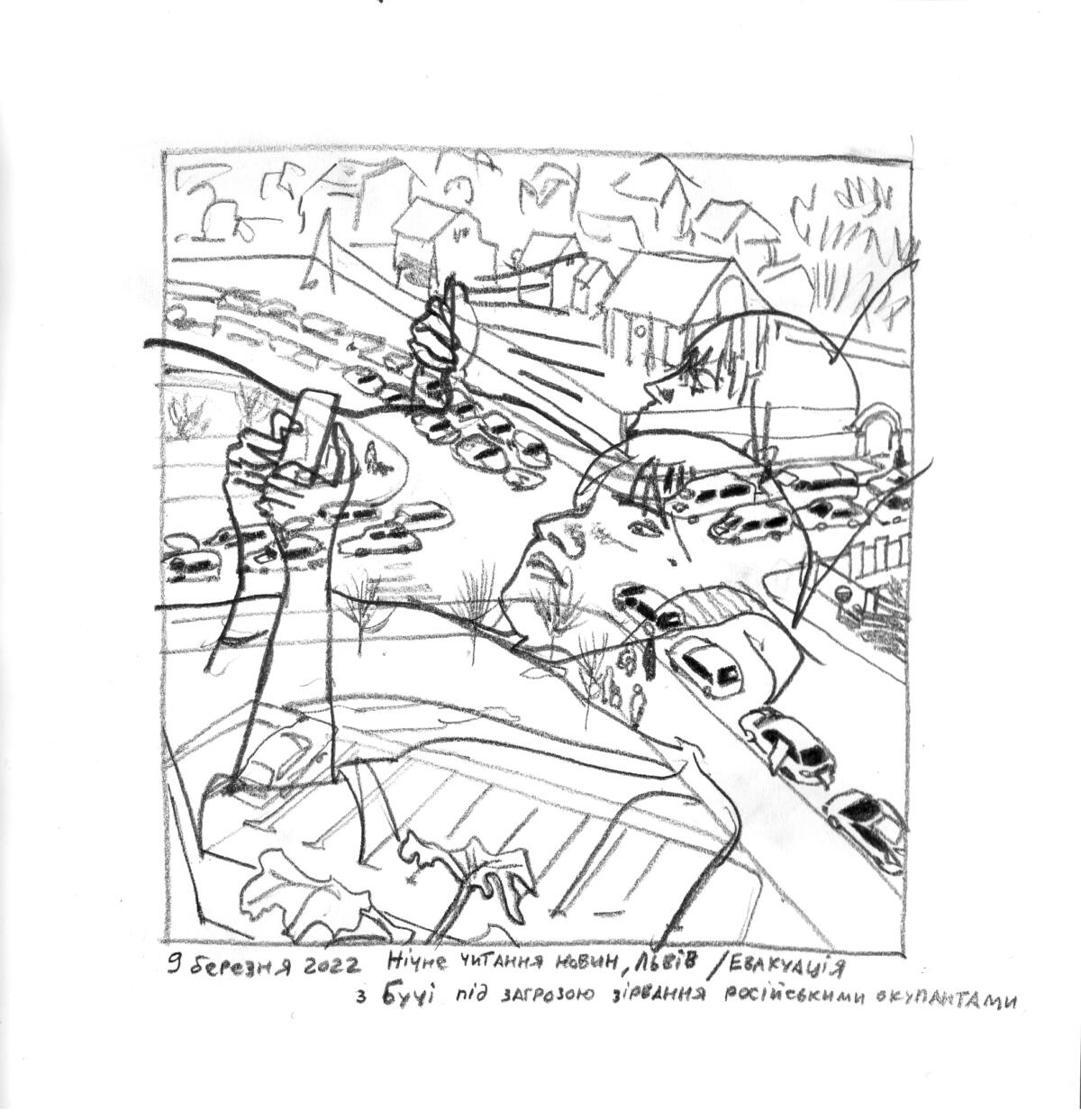

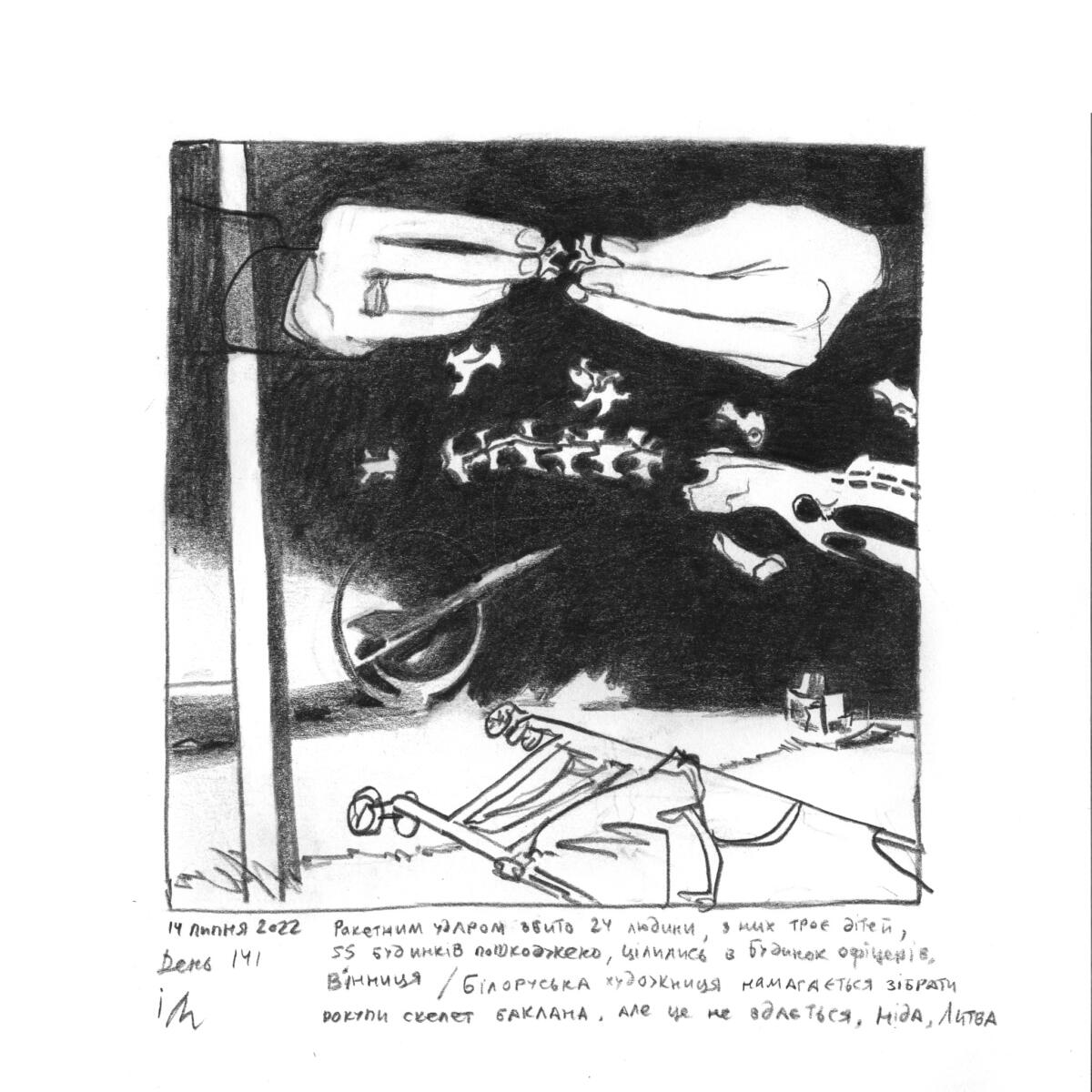

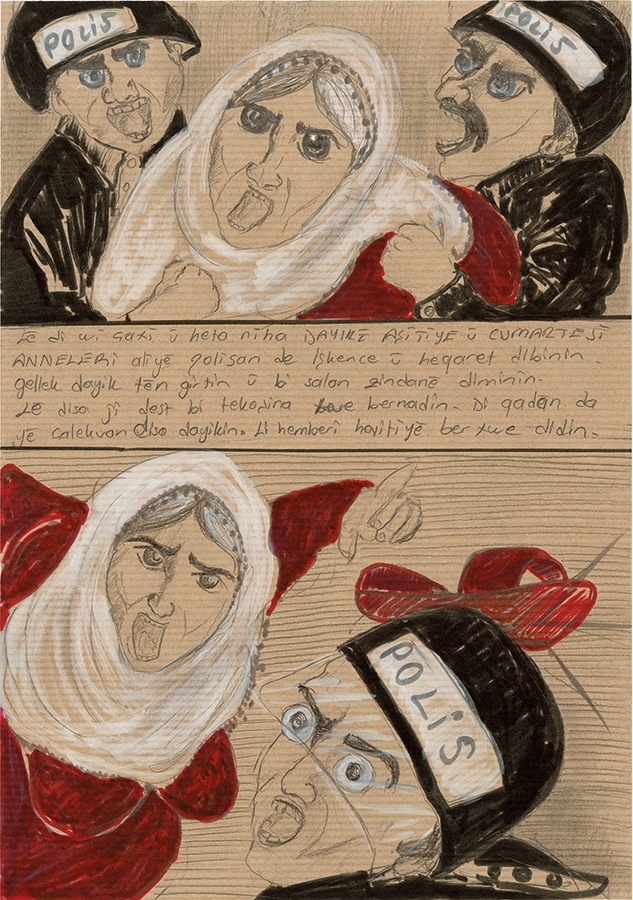

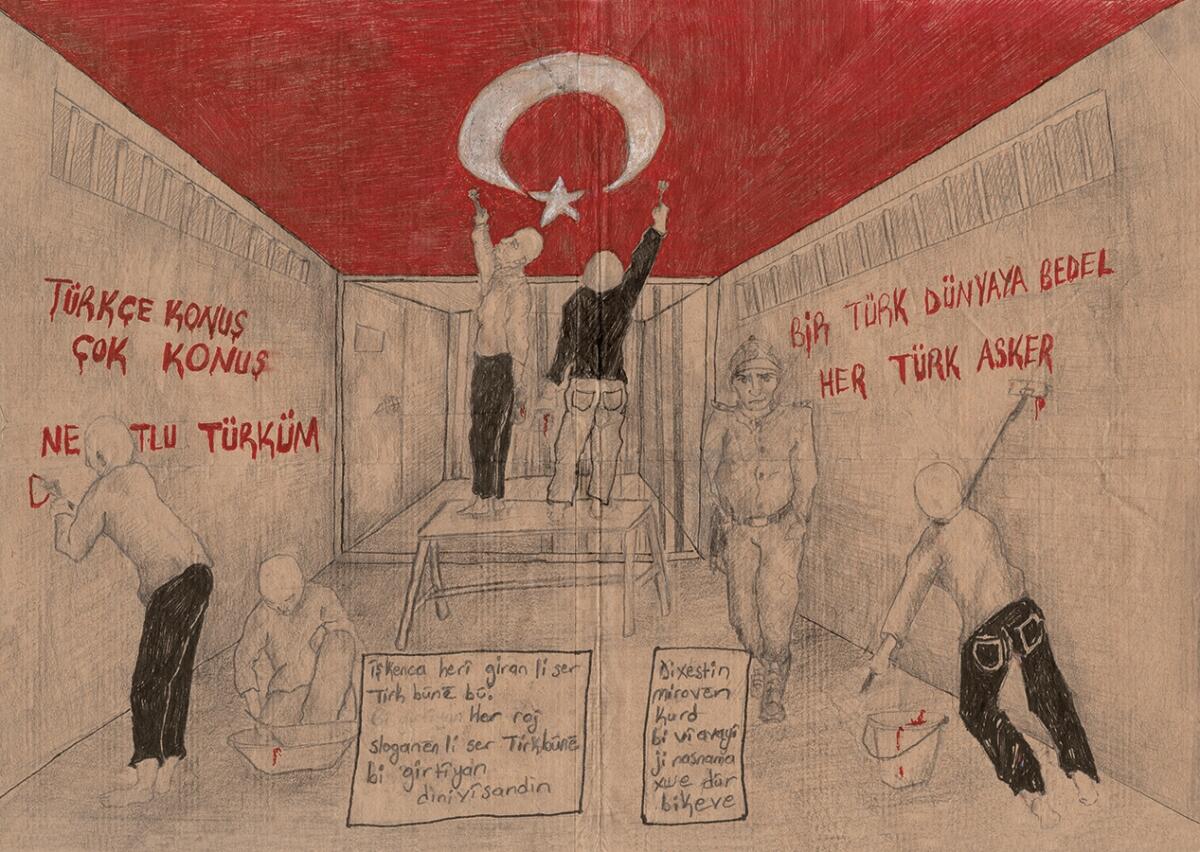

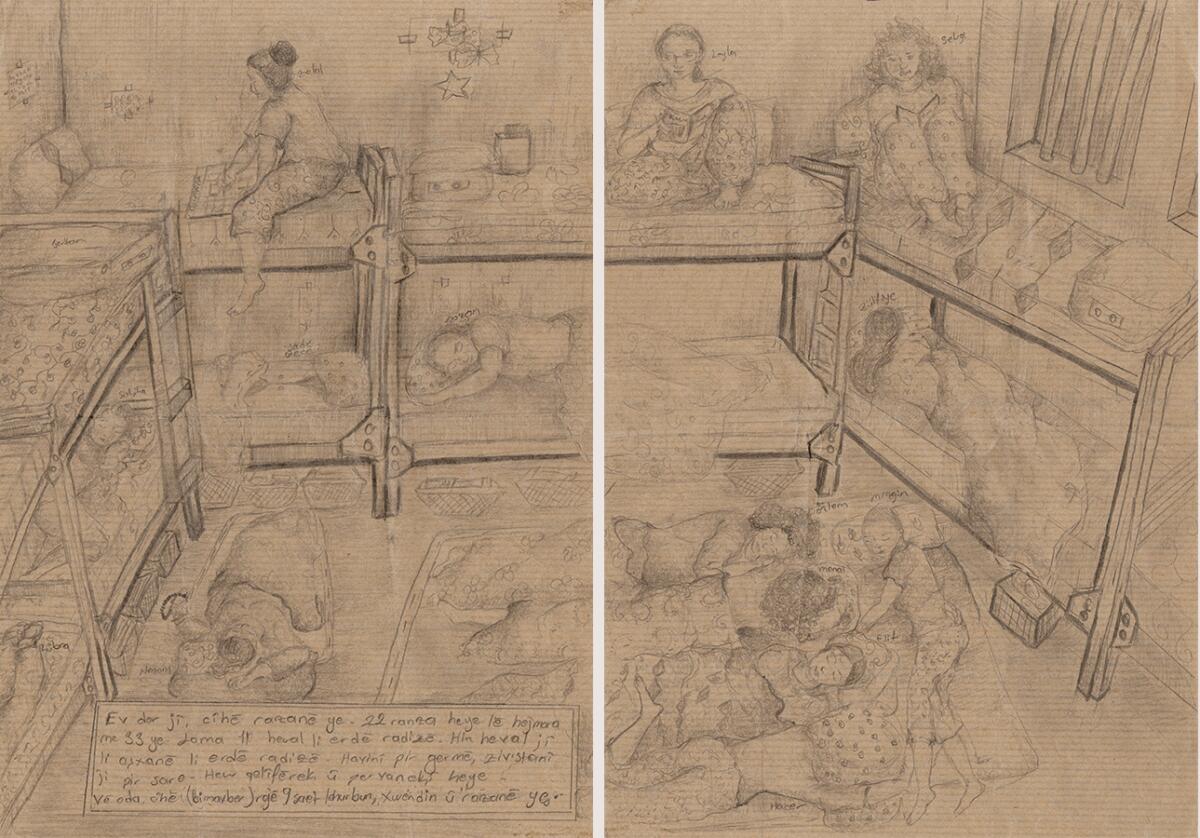

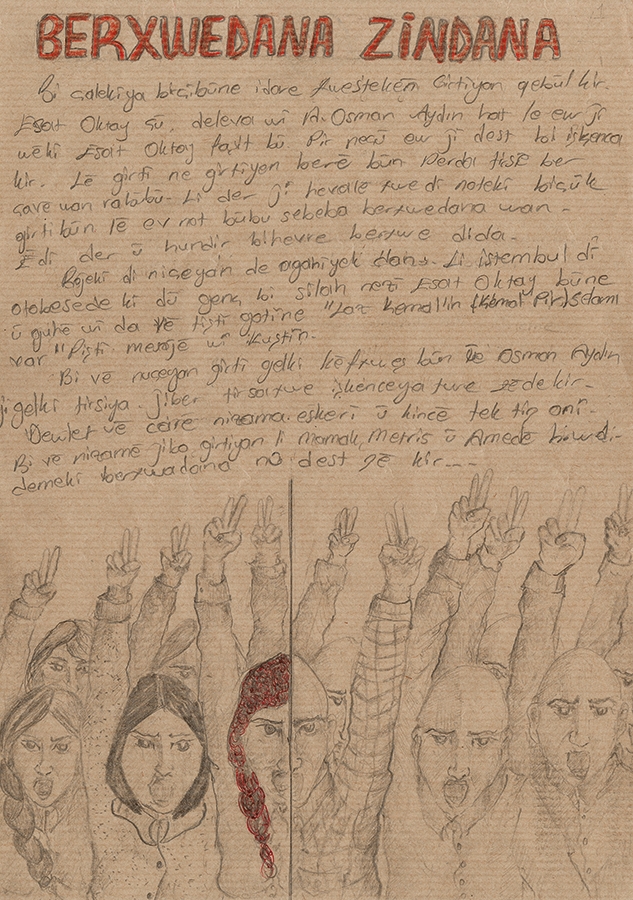

The dramaturgy of the works presented in the vicinity of the triptych is consistent. Like a dog sniffing a carcass, staring at the tied hands we assume the perspective of the torturer. On the largest canvas, which hangs nearby like a curtain slightly dividing the room, two young people carry a body. These paintings have the power of images from Bucza or Irpin. There is no doubt that they are documents of this war. Lyakh has also titled each work with a date, from May to November 2022, and includes a few sentences of contextual commentary. While the young Ukrainian does not put himself in the position of a victim, I see in these paintings an affinity with the drawings of Kurdish artist, activist, and journalist Zehra Doğan, created while she was incarcerated at a Turkish prison, which were shown at the Berlin Biennale in 2020. Or with the works of another Ukrainian artist, Inga Levi**, who showed a series of diaristic drawings from wartime Ukraine at the aforementioned exhibition at Galeria Labyrint. In the future, all of these works will have the power of historical records, but today they have a specific purpose, they force us to confront this war.

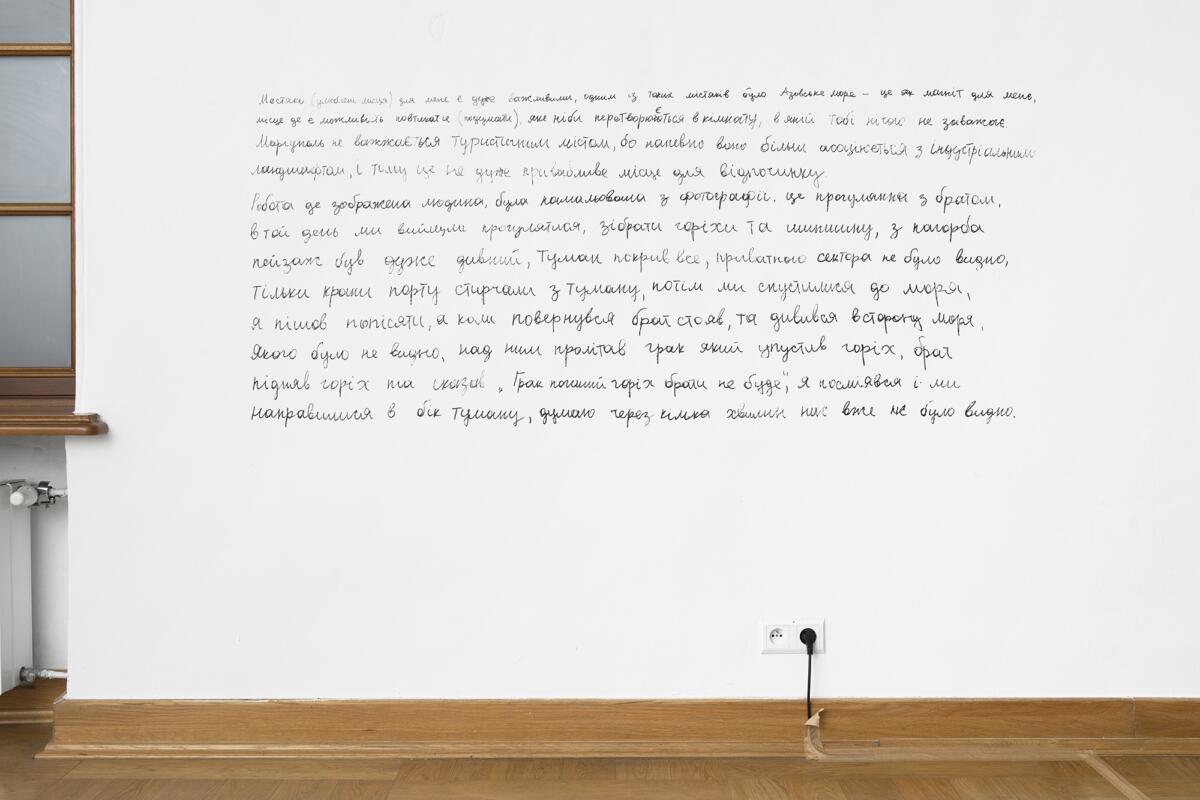

Yet still there is something else that lingers in Lyakh’s paintings. This becomes more evident in the second room, where only two paintings and a video were shown. The first is a stormy seascape of the Azov Sea. The second is a landscape that, although thousands of kilometers away, resembles the one we looked at from the car, on the road between Warsaw and Lublin. It’s the same kind of pale gray landscape, lit by the same pale gray sun, as if the colors of the world had been washed away. In the foreground, a small figure stands on a stretch of beach. The sand is scarred with ruts; whether these are traces of the military or the city’s residents’ leisure we don’t know. Beyond the beach, a void unfolds. Lyakh annotated the picture with this description: “That day we went for a walk with my brother, picking nuts and rosehips. The landscape seen from the hill was very strange. The fog covered everything. The houses along the coast could not be seen, only the harbor cranes stood out of the fog. Then we went down to the sea. I went to pee, and when I came back, my brother was standing and looking towards the sea, which was not visible. A rook flew over and dropped a nut. My brother picked up the nut and said: ‘The rook will not take a bad nut.’” In the painting, the fog has disappeared the city in the same way that Mariupol is being disappeared by the war, turning it into a ghost. Lyakh skillfully uses the landscape to tell his story of this place. When I look at this painting, I’m reminded of Wilhelm Sasnal’s Shoah, and perhaps even more so of one of the final scenes in Laszlo Nemes’ Son of Saul, when a group of escapees from the camp make their way through an alder forest near Auschwitz. Each of these works is a reminder that landscape, however beautiful or melancholy it may be, is never innocent. Landscape is political, and nowhere is this more evident than in Lyakh’s paintings.

Something important, however, distinguishes Lyakh from the two aforementioned artists, the Ukrainian does not play with history. He is not interested in what is left of the Ukrainian city, he is interested in the here and now – he paints what he himself has experienced through the stories of his friends and family. At the end of February, around the one-year anniversary of russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a debate was organized by Frieze magazine at the Sunflower Solidarity Cultural Center in Warsaw. The whole thing felt like a bad case of Westsplaining, especially as it was preached to one of the core communities at the epicenter of this full-scale war. But the meeting was worth squirming in a chair for an hour if only for the words of artist Kateryna Aliinyk. Aliinyk, a writer and like Lyakh, a painter, told the story of how she has crossed the border between russian-occupied and unoccupied Ukraine countless times in the past few years, which was both difficult for political reasons and cumbersome, as one always had to lug sacks full of jars of pear jam, pumpkin drowned in vinegar or kilos of nuts, all which added to the weight of the journey. She talked about how today she misses those heavy nets, because when the war escalated, those simple burdens somehow became sweetened. Lyakh’s best paintings express the same melancholy; a longing for life that while unpleasant, oppressive, and ugly as the winter in Warsaw and Kyiv, is simultaneously, inseparably ours.

*Editor’s Note: To create his works, Lyakh first collects stories from friends and family who are still living in Mariupol. He then enlists the help of close friends to stage scenes from these stories, inserting both his own body as well as those of his friends directly into the frame. The scenes are then photographed, which become the images that Lyakh uses to create his paintings.

Edited by Katie Zazenski

**Editor’s Note: The original article credited the works by Inga Levi to artist Anastasiia Pustovarova

Captions:

- Inga Levi, Double Exposure. 13 May 2022: A 16-year-old girl who was raped by a russian soldier during the occupation of her village / View from the parachute tower on the Peoples’ Friendship Arch which tomorrow will be renamed the Arch of Freedom of the Ukrainian people, Kyiv. Day 79. Works from the Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art (UMCA) collection, image courtesy of the artist.

- Inga Levi, Double Exposure. 9 March 2022: Night news reading, Lviv / Evacuation from Bucha is under threat of disruption by the russian occupiers. Works from the Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art (UMCA) collection, image courtesy of the artist.

- Inga Levi, Double Exposure. 14 July 2022: A missile strike killed 24 people, including 3 children, 55 buildings are damaged. They aimed at the “officers” house (those are cultural centres where concerts are usually held), Vinnytsia / Belarusian artist tries to assemble a cormorant’s (a type of aquatic bird) skeleton, she fails. Nida, Lithuania. Day 141. Works from the Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art (UMCA) collection, image courtesy of the artist.

- Inga Levi, Double Exposure. 27 June 2022: russian X-22 missile hit a shopping mall “Amstor” in Kremenchuk at 15:51. More than 20 people dead / Vilma Raubayte near a window in Thomas Mann’s Museum. The writing on her bag, from the Venice Biennale 2019, says “May you Live in interesting Times”…, Nida Lithuania. Day 124. Works from the Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art (UMCA) collection, image courtesy of the artist.

- Zehra Doğan, Prison n5 (2017-2019), Pages from a graphic novel made in prison, on the back of letters exchanged from 2017-2019. The pages left the prison clandestinely except for one of the drawings, which bears the stamp of the reading committee. Image courtesy of the artist.

This piece was originally published in Dwutygodnik on April 1, 2023: https://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/10589-gawron-nie-wezmie-zlego-orzecha.html

Imprint

| Artist | Vasyl Lyakh |

| Exhibition | Near/Far. Vasyl Lyakh Painting Exhibition |

| Place / venue | Promocyjna Gallery, Old Town Cultural Centre |

| Dates | From 8 February to 1 April 2023 |

| Curated by | Anita Nemet |

| Website | sdk.pl/galeria/blisko-daleko-wystawa-malarstwa-vasyla-lyakha/ |

| Index | Aleksander Hudzik Anita Nemet Old Town Cultural Centre Promocyjna Gallery Vasyl Lyakh |