Viewed retrospectively, the story that led to the creation of the Mnemosyne Atlas in 1929 could be told as a linear sequence of events. General preconditions played a role, including the steadily improving possibilities of technical reproduction in the early twentieth century and the rapid expansion of book publishing over the same period. There were also specific aspects attributable to decisions made by the Warburg family and Aby Warburg himself, above all the autonomy with which he was able to expand his research. Specific precursors are also identifiable, hints of the form that was to emerge in the late 1920s. There is a logic to the trajectory, especially when we consider the content, for Warburg’s final work draws together the research of the previous decades. Nevertheless, we are dealing with the invention of an instrument hitherto unknown to – and for decades rejected by – scholarship. Thus nobody should be surprised that there were difficulties associated with this project. It was only after Warburg’s death, however, that they proliferated in a quite different form with grave consequences. Hence we must keep in mind the fact that the Bilderatlas for so long remained largely invisible or appeared to be lost, as another of the mysteries inherent to this exceptional work.

But let us begin by retracing some easily comprehensible initial steps. When planning a lecture about Dürer in Hamburg in 1905, Warburg organised a small exhibition for his audience, with exhibits illustrating his thought processes. At the same time he commissioned three plates to be printed that reproduced some of the works discussed in the lecture as a hand-out for the audience.[1] Both aspects, the exhibition and the three prints, are significant steps on the long road to the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, which was originally conceived as a book project. It was in no way foresee-able – and still less intended – that the process of creating them would end up with images mounted on panels that have more in common with the medium of the exhibition. Our knowledge about this aspect of the story is itself a stroke of fortune; not always do archives grant such insights into how a workshop employs its resources for such experiments. Another unexpected turn is that the panels – ultimately the only result of the project – were inaccessible despite being comprehensively documented in photographs. In a sense they could even be said to have been invisible, as the originals in fact appeared to have been lost and the hitherto published reproductions were scarcely legible.

Even before the Dürer talk, Warburg had expanded the scope of his research to include the entire Early Renaissance, and soon he was also speaking of the necessity of publishing a major work on the period. It is in this connection that the first mention of an ‘atlas’ appears. But at that time the terms ‘Bilderatlas’ (lit.: ‘atlas of images’) and ‘Tafel’ (panel)[2] had no more than very general meanings in the publishing context. A ‘Bilderatlas’ was a volume of illustrations, which at that time still had to be printed using a different technique and on paper that was different from the text volume it accompanied. The same applied to plates included in a text volume: they were always bound separately, either as individual folios or sections usually at the back. The ‘Bilderatlas’ had been a product in its own right since the late nineteenth century, as a large-format stand-alone picture book focusing on a particular field of knowledge. It tended to be didactic and consisted principally of plates containing multiple smaller, individual illustrations. In other words, it prioritised an attractive appearance, while the explanatory texts were mostly general and brief. Advances in printing technology after the Second World War allowed a freer combination of text and image, and as a result the old terms, ‘Bilderatlas’ and ‘Tafel’, fell into disuse. Today they are used almost exclusively in association with Warburg’s project – lending them an air of significance and exclusivity that they did not originally possess.

‘Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas Mnemosyne – The Original’, installation view © Silke Briel / HKW

By the time Warburg held a series of lectures in Hamburg in 1909, the scope of his argumentation was already as broad as the later Bilderatlas: a highly condensed succession of seven chapters starting with Petrarch and ending with Dürer. To clarify the order of projected images he prepared a scheme that resembles the outline of the Bilderreihen (series of images) that he was not to produce until sixteen years later.[3] His quickly sketched thoughts clearly demonstrate the necessity for a different form. The complexity of the connections he wished to demonstrate between the works now transcended the linear confines of the slides he was still using at the time.

On 20 April 1914 Warburg gave a lecture on ‘The Emergence of the Antique as a Stylistic Ideal in Early Renaissance Painting’ at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, condensing no less than twelve hundred years of visual history into his talk.[4] There was something demonstrative about the act of collapsing such distances, connecting them with the reverberations of particular forms, gestures and images, and with the tensions involved in their actualisation. Warburg wanted to make the ungraspable tangible; he wanted to know how something that now appeared so self-evident originally came into being. This was a journey from the Arch of Constantine built in Rome in 315 AD to the fresco of the Battle of Constantine painted in the Vatican in the 1520s. A journey from the suppression of Classical Art to the conflicts triggered by its rediscovery in the fifteenth century.

Just four months later, Europe’s rulers plunged the continent into war. Warburg turned his visual research to the contemporary news media, conceiving sketches for three panels that are structured like a two-page spread in a magazine.[5] This detour into the violence of war propaganda might appear remote from his actual research interest: art history. What it did reveal was the material base shared by both: the modern communication technologies that were decisive for the life of images, for their movability or mobility, but which in 1914 also bore responsibility for the deaths of human beings.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, expeditions seeking to bring art and architecture of all epochs from the remotest outposts to the major Western cities were systematically using modern recording techniques. The Age of Mechanical Reproduction had begun – under conditions of colonial power driving territorial expansion externally and pursuing scientific rigour internally. The cultural assets that photography had rendered mobile were supposed to benefit the education of the home population. One prime example of the drive for modernisation and its intimate ties to industrial progress was the initiative of the British elites that led to the founding of the South Kensington Museum (today Victoria and Albert Museum). Every available form of reproduction was used to present art from all eras in the format of a permanent world exhibition. The most spectacular manifestation was the life-size reproduction of Trajan’s Column, which is still on display at the V&A today.[6]

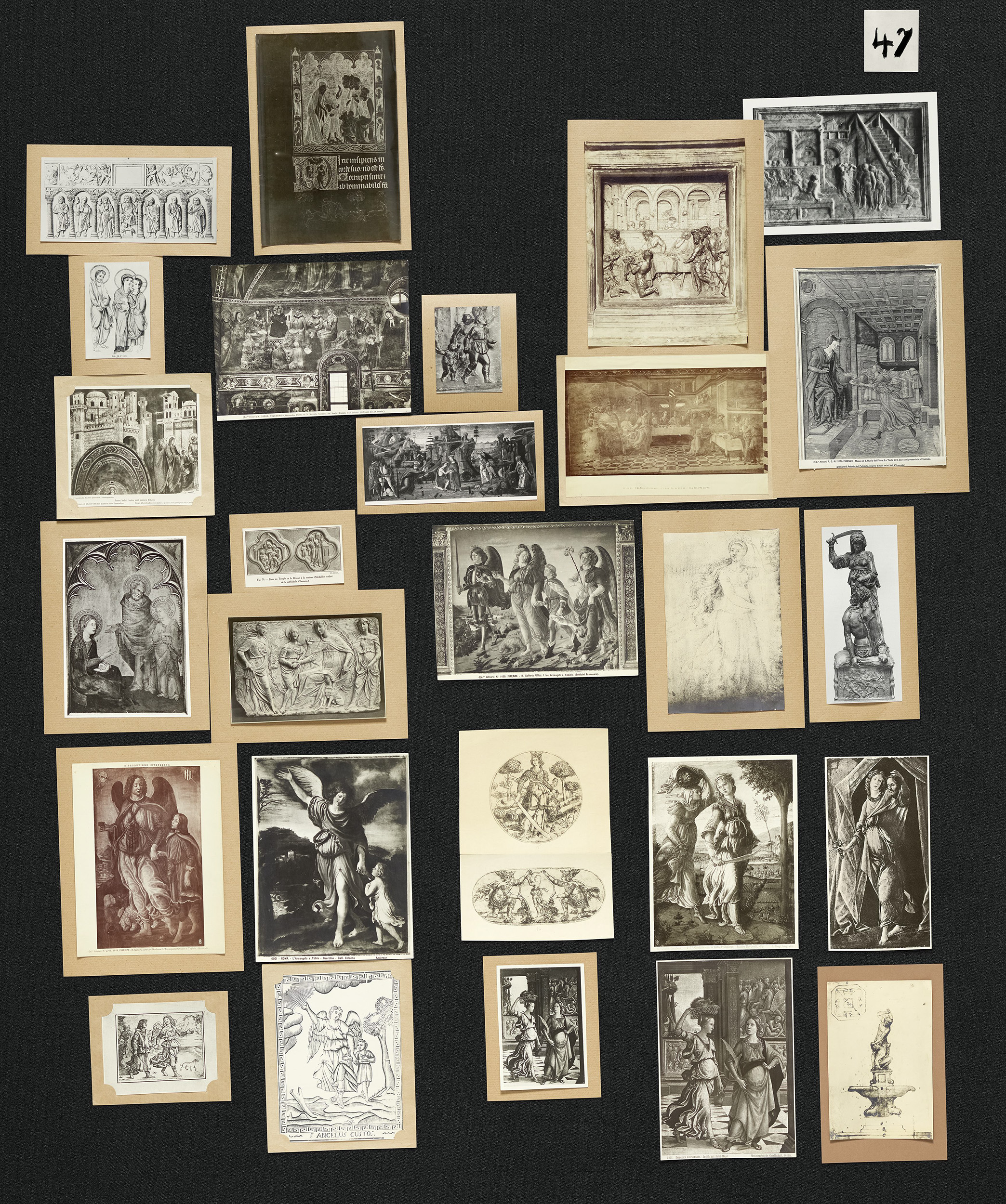

Aby Warburg, ‘Bilderatlas Mnemosyne’, panel 47 (recovered), photo: Wootton / fluid; Courtesy The Warburg Institute, London

Collecting reproductions was also a widespread artistic practice at the end of the nineteenth century.[7] On the walls of academies and studios they elucidated possibilities, suggested interpretations and supplied guidance within a canon that was largely based on the study of Antiquity and saw itself as realising the ideals of that age. Occasionally the possibilities to manipulate elements of form offered by printed reproductions on paper even led to experiments resembling the techniques of collage and montage that were to emerge in the twentieth century.

Ever since Wölfflin’s study of Renaissance and Baroque style, it has become evident that the way art appears in books has direct effects on how it is understood, a phenomenon that became a subject of discussion on more than one occasion.[8] But instances documenting how reproductions were treated in academic contexts are few and far between. Warburg made use of the possibilities of photography and spoke of its advantages, and we know a surprising amount about his practice because he always painstakingly documented his work and carefully considered every step.[9] But otherwise little is known about the ways media were used in scholarship. The International Exhibition of the Book Industry and Graphic Arts, which was staged in Leipzig shortly before the First World War, represents an exception in this respect; partly on account of the specific field, copious use was made of illustrations.[10] Karl Lamprecht, one of Warburg’s teachers, was involved, and the form and content exhibit astonishing similarities with the Bilderreihen and the Bilderatlas.

Another early example of systematic utilisation of reproductions falls in the immediate post-war period. In 1918 Fritz Saxl, since 1912 one of Warburg’s closest collaborators, organised a series of didactic exhibitions in Vienna in which he used exclusively reproductions.[11] Little is known about his concept, but he plainly wanted to bring art as a medium of knowledge to broader sections of the population and to persuade the public to consider questions that had been drowned out by the clamour of war propaganda. When Warburg returned to Hamburg from the sanatorium in 1924, Saxl prepared a little exhibition to welcome him, using visual examples from Warburg’s areas of research. One of the myths around the genesis of the Bilderatlas is that this was the moment when Saxl showed the ‘revenant’ new possibilities for working with art and laid the foundations for the Bilderatlas. In reality, this is not based in fact. Warburg had begun creating a photographic collection at a very early stage, both to advance his own research and to communicate his findings. Creating Bilderreihen and using illustrations to communicate his findings to a small circle of listeners was already part of his practice before the First World War. The Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg (K.B.W.) systematically expanded this instrument; once the new building had been completed in 1926 it also possessed a photographic laboratory and new techniques for reproduction.

Leaving aside the actual importance of Saxl’s exhibition, the two researchers decided then and there – perhaps swayed by the possibilities of photography – to create a Bilderatlas on the history of the Renaissance. Gertrud Bing, a doctoral student of Erwin Panofsky’s, entered the inner circle at this point and quickly became Warburg’s personal assistant. She was ultimately the person most closely involved in the evolution of the Bilderatlas. A broad understanding of the concept of enlightenment was crucial to the concept. The idea was that the book should open up a new perspective on the established values of art, both for experts and for a wider audience. Warburg became the driving force of the project, but always understood it as a collective undertaking: ‘Our Atlas’ did indeed emerge piece by piece out of the ‘research community’ at the Warburg Library. The Bilderreihen installed in the reading room between 1926 and 1928 represented its first stage.[12] Presentation in semi-public contexts was generally preceded by intense internal discussions or even trial sessions. Then Warburg gave his audience detailed explanations about the subjects and media of the complexly structured image constellations. Various external guests were invited, depending on the occasion, and all those who studied, researched or taught at the Warburg Library were able to attend.

‘Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas Mnemosyne – The Original’, installation view © Silke Briel / HKW

Vertical-format panels were used for the first time in spring 1928. These were boards covered with dark Hessian, roughly 150 centimetres high and 125 wide. The format was a major shift; until then the Bilderreihen had been horizontal.[13] Realisation in book form was plainly on the agenda and they were taking the standard publication format into account. By October 1929 three more or less clearly distinct versions of the Bilderatlas had been produced, all of which are documented in photographs.[14] The first, from 1928, encompassed forty-three panels. The second, with sixty-eight panels, was the most extensive and can be dated to autumn 1928, before the trip to Rome where the ‘dress rehearsal’ for the Bilderatlas was to take place, Warburg’s legendary lecture at the Bibliotheca Hertziana.[15] After returning from Italy Warburg fundamentally revised the concept, applying a chronological structure and developing the final version.[16] While the content of the panels, of which there were sixty-three by this stage, is noticeably clearer in the third iteration, new inconsistencies appeared in the numbering sequence: a gap between No. 8 and No. 20 and a smaller one between No. 64 and No. 70. Certain panels now bore more than one number – No. 28-29, No. 50-51 and No. 61-64 – where Warburg plainly planned to expand the content, and the lower-case letter ‘a’ identified two others as later additions: No. 23a and No. 41a were presumably inserted at a stage when subsequent panels had already been numbered.

Thus it stands beyond doubt that version three was not intended to be the final one. This is easy to explain: Warburg died on 26 October 1929. Some of the photographs documenting the final configuration were certainly taken only after his death. He had applied the new chronological structure to almost all the panels, but was far from finished. Obtaining an overview of the order and numbering was both necessary and difficult. We identified twenty panels in earlier versions whose images are completely absent from the last, and are therefore reproduced in a large format for the first time in the present volume.[17] Because the new structure involved sweeping changes these panels no longer fit into the gaps in the last version, and creating new spaces to accommodate the different chrono-logical stages of their development would have meant renumbering the entire sequence. Nevertheless, it is almost unimaginable that topics as important as Perseus or Bildpropaganda zur Zeit Luthers were simply to be dropped.

At the time, in 1929, the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne was neither conceived as an exhibition nor was it ever shown in its entirety. Along the curved shelf structure of the oval reading room – the backdrop for the Bilderreihen – there was only space to show about ten panels at a time. The room’s architecture, in which Warburg himself had been essentially involved, nevertheless played a notable role in structuring the Bilderatlas. Warburg appeared to have developed the panels in groups of ten (continuing with No. 20 and No. 70 respectively after the two gaps), within which a degree of coherence can be identified: Nos. 1 to 8 showing art in Antiquity, the ‘ancient models’; Nos. 20 to 27 for the return of the Gods from Arabian exile and their journey to the Palazzo Schifanoia; Nos. 28-29 to 39 for the first phase in Florence, until Botticelli; No. 40 to 48 for the second phase, until Ghirlandaio, the ‘Nympha’, and Fortuna; Nos. 49 to 59 for the after-effects (Mantegna, Rome, Raphael, Manet, Michelangelo, Dürer); Nos. 60 to 61-64 for the Age of Neptune, with the conquest of the Atlantic as the new key to power; Nos. 70 to 76 for Rembrandt and Antiquity; and Nos. 77 to 79 for the present day and a kind of résumé (counterbalancing the three introductory panels, which are identified by letters).

Gertrud Bing, Fritz Saxl and Edgar Wind, the most dedicated members of the K.B.W., pursued the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne publication project until well into the 1940s, in the latter stages at the Warburg Institute in London, where this unique laboratory of cultural studies remained safe from the Nazis. When it was shipped in December 1933 the collection comprised about fifteen thousand photographs, including more than two thousand images Warburg had selected for the Bilderatlas. It is unlikely that the Gestelle (as Warburg himself sometimes referred to the wooden supports for the panels) made it to London; they certainly never reappeared. Gertrud Bing engaged Ernst Gombrich in 1936 specially to prepare the Bilderatlas for publication. All he had to show in 1937 was a wispy intimation, but nothing that could ever have come close to the realisation of the intended book. Bing pursued her project of publishing Warburg’s late work into the 1940s, but was unable to assert herself against Gombrich.[18]

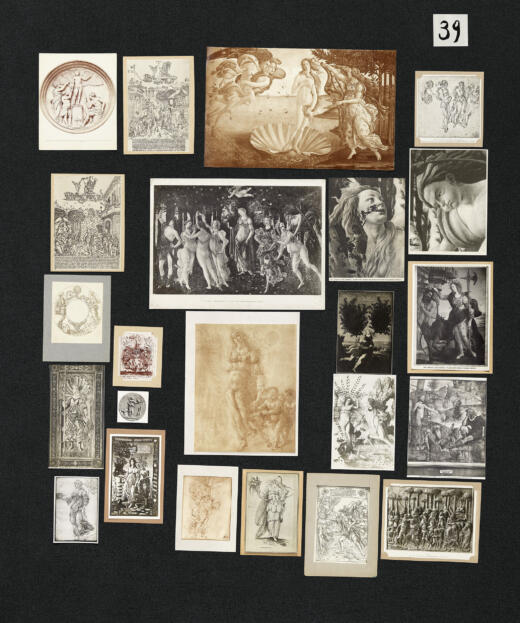

Aby Warburg, ‘Bilderatlas Mnemosyne’, panel 39 (recovered), photo: Wootton / fluid; Courtesy The Warburg Institute, London

That is not where the story ends, unfortunately. For his failure to fulfil his task, Gombrich blamed the initiator of the project. In his so-called ‘Intellectual Biography’ he characterises Warburg as lacking the necessary organisational talent and methodological rigour to complete the Bilderatlas.[19] In other words, its creator’s ‘shortcomings’ were etched into the Bilderatlas as an irresolvable structural or conceptual problem. This assessment was to determine the afterlife of Mnemosyne for decades and ultimately represents one central reason why the original illustrations lay neglected in the Photographic Collection of the Warburg Institute for almost a century. While researchers came to believe that the Atlas had been lost, in fact the 971 photographs had been sorted back into the Photographic Collection at some point in the course of the 1930s – without any record of exactly where. The last remaining evidence of the individual elements on the sixty-three panels was lost in the 1940s when the Collection was indexed iconographically at Rudolf Wittkower’s instigation. By 2019 the Photographic Collection had grown to about four hundred thousand items: a sea of images out of which the originals now had to be recovered.[20]

In its final version the Bilderatlas remains a fragment, abruptly truncated in the process of its development. Yet it bears no resemblance to a kaleidoscope, where the next rotation might create a new random pattern of pretty colours. The panels definitely gain in precision from the first version to the last; they are increasingly more clearly structured and more legible. It would be unreasonable – and unproductive – to treat them as a transient moment in an ever-changing process, whether professing sympathy for their ‘artistic character’ or – as Gombrich does – alleging a lack of scientific rigour. All presentations of the Bilderatlas prior to this volume, whether in book form or an exhibition, have been based on the black and white photographs from the 1920s.[21] For the viewer today our recovery of the original relativises the effect of uniformity and strengthens – to put it bluntly – the impression of chaotically distributed visual components (which precisely reflects the prejudices of critics and supporters in the past). Therefore, at first glance ‘the original’ might appear to confirm what so long stood in the way of it being properly appreciated. Lack of clarity and the revelation that it is a work in progress might distract from the precision of the content or simply cause irritation, but the visibility of the different sources also highlights the experimental nature of the undertaking. The element of montage becomes more apparent, the impulse to extract something new from the sources as well – and this we must grant Warburg, even if we understand his conceptual venture as a struggle for clarity and more keenly comprehend the thoughts he is formulating between the images. In the dimensions in which they have been rendered in this volume the reproductions now permit the panels to be examined in detail. It thus becomes possible to make proper use of them and should help dispel the long-standing reservations.

To a certain degree, the original colour tones of the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne lead back to the moment of its invention, and as such to all the difficulties associated with an endeavour for which there were virtually no precedents. Not all of these difficulties were resolved – and at this point it is obsolete to do so – but neither can we simply pass them over. Warburg’s book would certainly have had a different appearance. The panels were not conceived as the final manifestation of his project. Yet in this form they offer us a two-fold opportunity: on the one hand, to explore the full complexity and precision of a process that was interrupted on 26 October 1929 and to face the same challenge as Warburg did; on the other hand, the productivity engendered by the fragmentary and incomplete nature of the work need not be constrained by demands for a definite conclusion. Instead, we hope that the present publication will serve as a tool for future expeditions.

It is therefore not our intent to retrieve reproductions and present these as ‘originals’. First and foremost, we wish to pay tribute to a body of work that Warburg sought to shape until the very end of his life, aiming to achieve thematic precision and a certain openness, which he felt was crucial to maintain towards the aesthetic material he explored. He occasionally characterised his method as ‘polyphonic’ and ‘multi-dimensional’, which is why the Bilderatlas was so exceptionally difficult to complete.[22] Up to now, this appreciation of his work has been denied to him. In itself, this book required a particular form, size and quality; and although we know we could not realise the work that Warburg had hoped to accomplish, his ambitions – and the vast potential provided by the library he created – were key to our endeavour: ‘I use the books like instruments in a scientific laboratory.’

The text is an excerpt from Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas MNEMOSYNE – The Original, edited by Roberto Ohrt and Axel Heil and published by Hatje Cantz. The publication accompanied the exhibition at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin.

[1] Marcus A. Hurttig, Die entfesselte Antike: Aby Warburg und die Geburt der Pathosformel in Hamburg (Cologne 2012).

[2] The term normally refers to ‘plate’ in English, but specifically in connection with the Atlas it denotes ‘panel’.

[3] Giovanna Targia (ed.), Aby Warburg – Il primo Rinascimento italiano, sette conferenze inedite (Turin 2013); sketch p. 145 ff.

[4] Martin Treml, Sigrid Weigel and Perdita Ladwig (eds.), Aby Warburg: Werke in einem Band (Berlin 2010), p. 281 ff.; held in Florence on 20 April 1914.

[5] Steffen Haug reconstructed these panels while a Frances Yates Fellow at the Warburg Institute (2017/18), in the scope of a project on the First World War.

[6] ‘Saving’ the past is frequently understood to mean ‘rescuing from deterioration’ or ‘bringing back to life’. This stance is often discernible in the self-perception of colonial collections vis-à-vis artefacts arriving from distant cultures.

[7] See Roberto Ohrt, “Die Erinnerung im Archiv ihrer technischen Reproduzierbarkeit”, in: Café Dolly. Picabia, Schnabel, Willumsen. Hybrid Painting, Willumsens Museum Frederikssund 2013.

[8] Heinrich Wölfflin, Renaissance und Barock: eine Untersuchung über Wesen und Entstehung des Barockstils in Italien (Munich, 1888). (Published in English translation in 1966 as Renaissance and Baroque by Cornell University Press, translated by Kathrin Simon.)

[9] Explicitly in Aby Warburg, ‘Bildniskunst und florentinisches Bürgertum’ (Leipzig, 1902), in idem, Erneuerung der heidnischen Antike: kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge zur Geschichte der europäischen Renaissance, reprint of the 1932 edition, edited by Gertrud Bing with Fritz Rougemont. Published as Gesammelte Schriften: Studienausgabe, vol. I. 1, and vol. I. 2, edited by Horst Bredekamp and Michael Diers (Berlin, 1998), pp. 89 ff., esp. p. 101; see also Mick Finch, ‘The Technical Apparatus of the Warburg Haus’, Journal of Visual Art Practice, vol. 15, no. 2–3, pp. 94–106.

[10] Halle der Kultur, Internationale Ausstellung für Buchgewerbe und Graphik, Leipzig 1914. We are grateful to Marcus A. Hurttig for pointing us to this exhibition, which was reportedly seen by 2.3 million visitors. See also Aby Warburg: Mnemosyne Bilderatlas: Rekonstruktion – Kommentar – Aktuali-sierung, exh. cat. ZKM (Karlsruhe, 2016).

[11] Steffen Haug, ‘Fritz Saxl’s Exhibitions in Vienna (1919)’, in Image Journeys: The Warburg Institute and a British Art History, edited by Joanne W. Anderson, Mick Finch and Johannes von Müller (Passau, 2019), pp. 105–13. It has, regrettably, proven impossible to locate any photographic documentation on the exhibitions.

[12] Aby Warburg, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. II 2, Bilderreihen und Ausstellungen, edited by Fleckner and Woldt (Berlin, 2012). The book fosters the impression that ‘Bilderreihen’ were only produced in the preparatory work for the Atlas. There is various evidence for the self-conception of the ‘Arbeitsgemeinschaft’ (research community) that formed at K.B.W., first and foremost: the ‘Widmung’ (dedication) to Aby Warburg, in Ernst Cassirer, Individuum und Kosmos in der Philosophie der Renaissance (Hamburg, 1926); and the collective journal of the Warburg Library, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. VII: ‘unser Atlas’, p. 148.

[13] It is not possible to determine the dimensions any more precisely, because the position of the camera in relation to the panels varied.

[14] The second – and most extensive – version is in fact documented with three different sets of numbers; the content and extent of the panels varies little. Occasionally the numbers were also amended on the negatives.

[15] On the lecture at the Bibliotheca Hertziana see Aby Warburg, Gesammelte Schriften, vol. II 2, Bilderreihen und Ausstellungen (see note 11).

[16] Research on the early versions is nascent. Katia Mazzucco distinguishes five different stages of the Atlas (Katia Mazzucco, ‘Il Progetto Mnemosyne di Aby Warburg’, Ph.D. diss., Siena University, 2006), Joacim Sprung, six (Joacim Sprung, ‘Bildatlas, åskådning och reproduktion: Aby Warburgs Mnemosyne-atlas och visualiseringen av konsthistoria kring 1800/1900’, Ph.D. diss., Copenhagen University, 2011, p. 16 ff.). For the sake of simplicity we will confine ourselves to three versions here; the intermediate versions differ principally in their numbering but to a much lesser extent in the imagery itself. Panels from the early versions have been published only sporadically and unsystematically.

[17] On pp. 152 – 171. Creating an index for these panels was beyond the resources of the present project. The concordance (p. 173 ff.) gives pointers for thematic orientation.

[18] The Gombrich version was presented to Max Warburg on the occasion of his seventieth birthday and is referred to in the literature as the ‘Birthday Atlas’ (‘Geburtstagsatlas’). Some of its ‘panels’ have been published in various books as historical documents. On the unfortunate relationship between Gombrich and the Warburg Institute see Claudia Wedepohl, ‘Critical Detachment – Ernst Gombrich as Interpreter of Aby Warburg’, in Vorträge aus dem Warburg-Haus, vol. 12, The Afterlife of the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, edited by Uwe Fleckner and Peter Mack (Berlin 2015).

[19] Ernst H. Gombrich, Aby Warburg: An Intellectual Biography, 2nd ed. (Chicago 1986).

[20] For details of the recovery, see our contribution ‘On the Recovery of the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne and the Completion of the Captions’ in this volume, p. 21.

[21] The first series of exhibitions was initiated by Daedalus in Vienna in 1993, the second by the research group Mnemosyne in 2012 (Hamburg, 8. Salon). Both produced black-and-white reprints to investigate the Bilderatlas in detail.

[22] Warburg used the ‘multi-dimensional’ panels as tools in his quest for constructing the Atlas until the final days of his life. Thus, it is erroneous and misleading to assume that in the summer of 1929 he would employ a folder with unbound plates as a solution to the difficult question of the most optimal form of publishing the Atlas. In fact, he had already found this ‘one-dimensional solution’ 24 years earlier in the course of preparing his Dürer lecture. Cf. Christine Kreft Adolph Goldschmidt und Aby M. Warburg (Weimar 2010), Warburg in his letters to Goldschmidt, pp. 145 and 220. The concluding quotation is taken from a letter written in 1918, see: Dorothea McEwan, Ausreiten der Ecken. Die Aby Warburg – Fritz Saxl Korrespondenz 1910 bis 1919 (Hamburg 1998), p. 16.

Imprint

| Artist | Aby Warburg |

| Exhibition | Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas Mnemosyne – The Original |

| Place / venue | Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany |

| Dates | 4 September – 30 November 2020 |

| Curated by | Roberto Ohrt and Axel Heil in cooperation with the Warburg Institute |

| Publisher | Hatje Cantz |

| Published | 2020, London |

| Website | www.hkw.de/en/index.php |

| Index | Aby Warburg Axel Heil HATJE CANTZ haus der kulturen der welt Roberto Ohrt |