There have been many myths about origins of art, mostly they begin with drawing, allegedly the cradle of representation. History shows that this art is never fussy about its canvas and emerges on anything that provides it with a flat surface – rock, wood, or a body. Tattoos are equally associated with primitivity given its tribal provenance. Maurycy Gomulicki in his last project “Tats”, exhibited now in Zachęta National Gallery of Art, explores this obscure area of untamed creativity, creating a captivating essay on nexus of art and corporeality.

Gomulicki assumes here the role of anthropologist who investigates and documents the culture of social margins, whose manifestation are the eponymous tats. He is interested in the unskilled, crude roots of the tattooing art which can be found in ‘sites of oppression’: prisons, military forces, detention centres. In such environments there is no intermediary between the primal urge to express and the realization of such a need. It is clearly not a kingdom of bon gout: the harsh reality supresses sophisticated aesthetics, favouring simplicity and immediacy. Thus, forms are not ossified yet, they still remain directly connected to the affect that have engendered them. Tattoos in this light present a curious investigator with an experimental field that resembles the circumstances in which art is born. Gomulicki traces this process on the bodies of his sitters, portraying their figures in a quite sensual way, balancing between cold ethnography and artistic fascination.

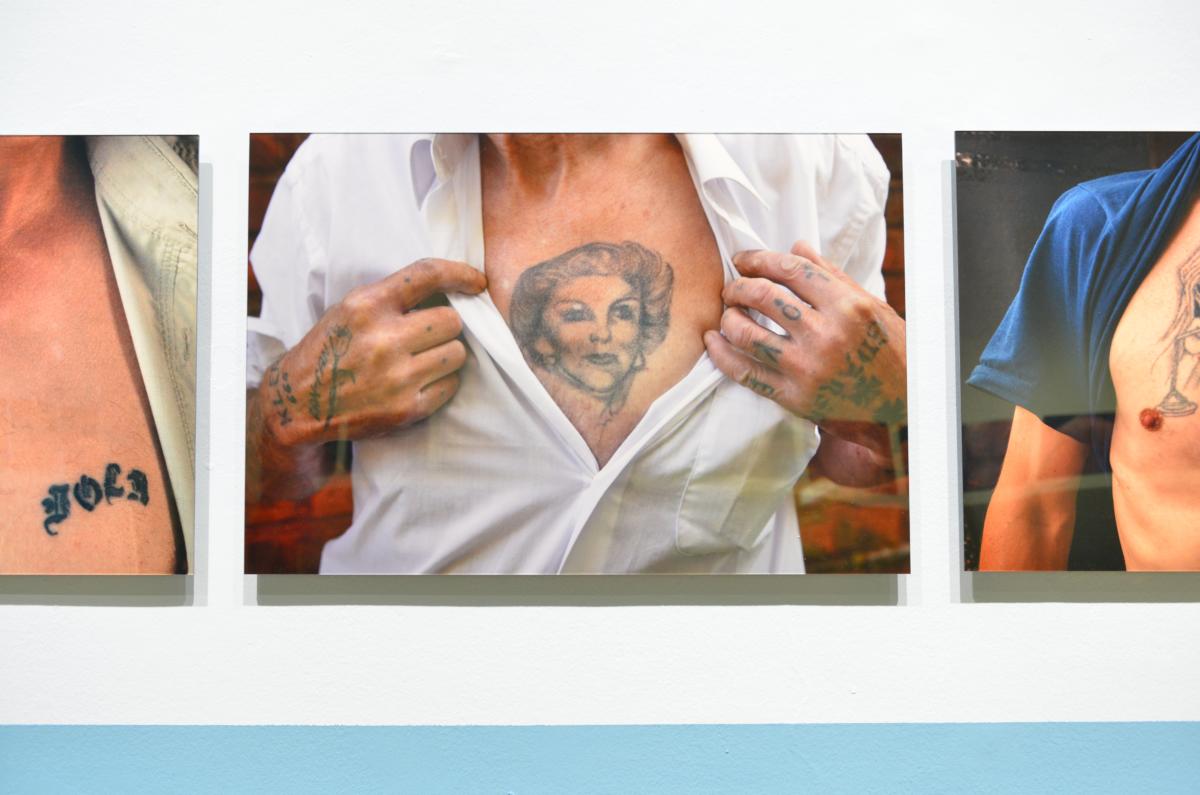

The exhibition leads the viewers through three rooms wherein display is simple and moderate so as not to distract from the photographed bodies. Yet, the gallery space is arranged to punctuate issues crucial to Gomulicki’s project. A couple of murals repeat the patterns of tattoos and this gesture extracts the potential of the drawings in their linear nature from the individuality of each body. The Neorenaissance style of the interior bestows monumentality on the photographs, particularly striking in the triptych that greets the viewer on the door. Those people from the margin appear suddenly as mythological, vigorous figures, bizarre and brutal heroes. Each of them present physical fitness, which is portrayed carefully: muscles, veins and wrinkles are offered to our scrutiny, sensuality of these images is beyond any doubt. Flesh and ink, inexorably intertwined. We confront an odd pantheon of utterly physical heroes, retired warriors immortalised in a twofold way: firstly, in photographs that aggrandise them, and secondly, via the fabric of patterns that covers their body. The photographic collection reveals, out of a sudden, a myth-creating function of tattoos: they may operate as an epos that recapitulates the hero’s deeds. The intertwinement of the body, the individual’s history and art creates a hero. It seems that this is a reciprocal relationship insofar as the hero consolidates importance of art and representation transforms an individual into a (heroic) story. The last room shrouded in darkness, illuminated only with dimmed light of a projector, presents the ultimate stage of this process, a final apotheosis as the images leave their frames and cover an entire wall, in a reminiscence of a primal sanctuary. This transposition liberates the drawings from their specific contexts, but at the same time this gesture accentuates the heroic silhouettes of the photographed people. They are not retired machos anymore as the grandeur of representation confers ultimate meanings on them; They resemble Hercules in the moment of transfiguration when terrible flames devoured his body, on the edge between the mortal and the eternal. By the same token, those worn-out bodies reached the point when their burden transforms them into heroes, and beyond, into a sign, a constellation, a story.

However, Gomulicki is not concerned with classical beauty and his Herculeses are painfully mundane – they had been given the Nessus’s shirt very early and it destroyed them. While for the Greek hero it was the envy and greed that defeated him, in case of these heroes it was the very environment they lived in. This is issue is suggested by the elegant display which alludes to interiors specific to administration and institutions of power. The horizontal lines of crown moulding, dado rails and skirting board comprise a standard visual framework for all Eastern European spaces of power and, arguably, nearly everywhere, given the imperial overtone of neoclassicism. The interiors’ architecture reminds us gently about mechanisms of oppression under which the tattoos developed. We can easily imagine Gomulicki’s Herculeses trapped in those spaces: cells, waiting rooms, crowded dorms. Their disagreement to the system is not romantic or moral, yet it is real and consequently executed, in which it resembles the struggles of the original Greek hero against the gods. And eventually, one can imagine how out of this frustration grows a need of exclamation – the primal scream mentioned by the artist in his interview for Zachęta. A study in art suddenly turns out to be an investigation in power relations. The display by this visual reference suggests that out of the relationship of pressure and resistance, expression arises nearly miraculously and inevitably.

Gomulicki is not concerned with classical beauty and his Herculeses are painfully mundane – they had been given the Nessus’s shirt very early and it destroyed them.

Nevertheless, the interest of the artist does not lie primarily in the social tissue. It is rather the honesty of representation and the rudimentary motivation to create that fascinates Gomulicki. In the Pliny’s version of the genesis myth, art begins with a loss: a young girl has to part with her lover who is going to war. While he’s sleeping, she secures the memory of him by tracing his shadow, and thereby creates the first depiction. In the paradigm proposed by Gomulicki, there is no prototype in the first place – the loss is not anticipated, it has already happened as it is deeply embedded in the social reality. The artist describes this art as ‘primal scream’ – manifestation of bare human condition. Comparison with the Pliny’s myth heightens longing that pervades such representations. Images of desire, power, and resistance engraved in flesh compensate for the essential lack of them in the situation of repression. In the absence of a woman, the Woman descends on the skin of the desiring subject.

This immediacy of translation – emotion into an image – inevitably fascinates as it transcends the antagonism of form and content. It is a perfect union of both aspects, yet it is not formal sophistication that makes it possible; the emotional saturation of those images validates their form – it is the genuine personal attachment which turns these nearly childish drawings into irrefutable symbols. Tattoos then operate within the blurry zone between conscious and unconscious, testifying the miracle of semiosis.

Gomulicki behaves like an archaeologists who follows the paths of linear representation until he finds its source.

Furthermore, the so-called primitivity (as one has to be always cautious with this term) of those images gives us an insight in the development of drawings. Gomulicki behaves like an archaeologists who follows the paths of linear representation until he finds its source. As the curatorial note states, the artist tells the story of the art of drawing with particular emphasis on the idea of disegno, a Renaissance term that denotes design, pattern, plan of a thing. Disegno requires knowledge, in which it resembles a blueprint; a visual scheme of the abstract essence of the represented object. Tattoos in this sense undoubtedly are natural carriers of disegno as they reduce objects to its essential features. In Albertian sense, tattoos due to their rudimentary character are devoid of historia, a counterpart of disegno on a compositional plane. Historia is usually understood as the narrative element of the image, it is the temporal and emotional dimension which drives the composition, and ultimately, ascribe it to a specific genre. However crucial historia is for the Renaissance theory of painting, it is nearly absent in tattoos documented by Gomulicki. This is because both terms express divergent ontological aspects – for disegno represents objects as they ideally are, whereas historia is an actualization of those. And just as these tattoos are concerned with primary emotional states, so does its formal aspect which restrain itself to design the structure for those abstracts. To put it another way, those depiction do not tell any story, they stand for it. The myth they create is comprised of universalities, devoid of specificity, and thereby it alludes to every imagination across time. In that sense, this rudimentary art of tattooing is ahistorical, as it precedes formation of genres, styles, etc; It is the always busy, still undetermined nucleus of creativity.

“Tats” are a visual essay on human expression but also on emergence of symbols. Beside human stories, the exhibition witnesses the becoming of myth – its birth and consolidation on a living body. Gomulicki created a mysterious temple of a chthonic deity that embraces at once the physical corporeality and the mythical land of heroes, fulfilled desires, and accessible power. Most importantly, however, “Tats” are a documentation of art at its most authentic, purest moments. Whatever goes further, it is simply a flamboyant stylization.

Imprint

| Artist | Maurycy Gomulicki |

| Exhibition | Tats |

| Place / venue | Zachęta — National Gallery of Art, Warsaw |

| Dates | 21 August – 28 October 2018 |

| Curated by | Agnieszka Szewczyk |

| Photos | Marek Krzyżanek |

| Website | zacheta.art.pl/en/?setlang=1 |

| Index | Dominika Tylcz Maurycy Gomulicki Zachęta – National Gallery of Art |