The First One: The Ship

The room needs to be cleared fast. Everybody has to hurry, run towards the exit leading onto the deck. The nearest one is to the left of the stairs, there… right next to the hall of mirrors. Hopefully they won’t confuse you. Past the mirrors, go straight on. Only yesterday, the ship’s bunker was packed with people, so many of them that each passing day crushed any hope for food and water. On some days thirty would die. Of hunger. Of exhaustion. Those who still have energy frantically try to struggle onto the upper deck. It is the twelfth minute after the strike, twelve minutes from when the artillery shells and tens of air rocket missiles are launched. There is no time to count. Twenty, perhaps thirty strikes… The smoke soars to the sky in several trails, the starboard lists more and more treacherously. From afar, it is difficult to tell if it is the Thielbek or the Cap Arcona that is giving so much smoke. A few more minutes and the Thielbek sinks. It gradually disappears, leaving behind scraps of equipment, floating bodies and a few passengers still struggling to survive. In a couple of days, it will be asked what remains. In the see, they will expect to find the traces of the past.

Steamships moored in the Neustadt Bay near Lübeck: two cargo ships, the Thielbek and the Athen, and two passenger ships, the Cap Arcona, the Deutschland. In their cargo holds, prisoners evacuated from the Neuengamme concentration camp in Hamburg await their post-camp future. They are greeted with bombs dropped by the RAF. This is a grievous mistake. The cannon fire is incessant as they jump into the water. The municipal archive of Neustadt in Holstein holds perhaps the one and the only surviving photograph of the disaster of 3 May, 1945, a disaster shrouded in mystery. In the foreground, a fragment of a window left ajar; further on, the coastline, and in the background, looming images of ships blurred into one shape. The sea will spit the bodies of the perished onto the shore and the Allies will give the order to bury them in mass graves. To the local people.

Oblivion is a state in which we are aware neither of time nor of space. We also forget about their limits and borders.

Sława Harasymowicz, ‘The Bay’, 2020, Archeology of Photography Foundation, photo: Anna Hornik

The Second One: Sludge

Sludge is a camouflage expert. It dissolves traces and covers remains. A criminologist would call it a silent witness, since the matter of silt inconspicuously removes the evidence of events from the surface of water. Through its causative, erosive nature and self-imposed rules, it not only blurs, seals, overlaps or preserves remnants of history, it also provides shelter for unwanted evidence and stores away personal mementos. But one must excavate them.

Eight hundred tonnes of sludge formed the cemetery of the Thielbek disaster. Silt was raked away from one level of the underwater grave after another, layer by layer. Four years after the ship had sunk, it was pulled to the shore with heaps of mud, slime and deposits. To be delved into, sifted through, and sorted. To retrieve everything that could have possibly survived – human bones, spoons, and items that would help identify 122 people. These procedures, carried out by the employees of a hired private company, brought to mind the precise selection of concentration camp prisoners’ possessions: clothes and garments in one pile, and in another, the emptied suitcases of those who had just been transported and were heading in the opposite direction. Next to those, family silverware, jewellery, valuables, gold teeth. Nothing was to be wasted. Everything was to be taken to the Reich and the Nazis, to be put to good use. The shipwreck sludge hid no treasure at all. Cleaned of all evidence of the tragedy, renamed the Reinbek, the ship was sold by the Knöhr and Burchard forwarding company to a new shipowner and registered in Panama. Later, its name would be changed twice more – first to the Magdalene, and then to the Old Warrior.

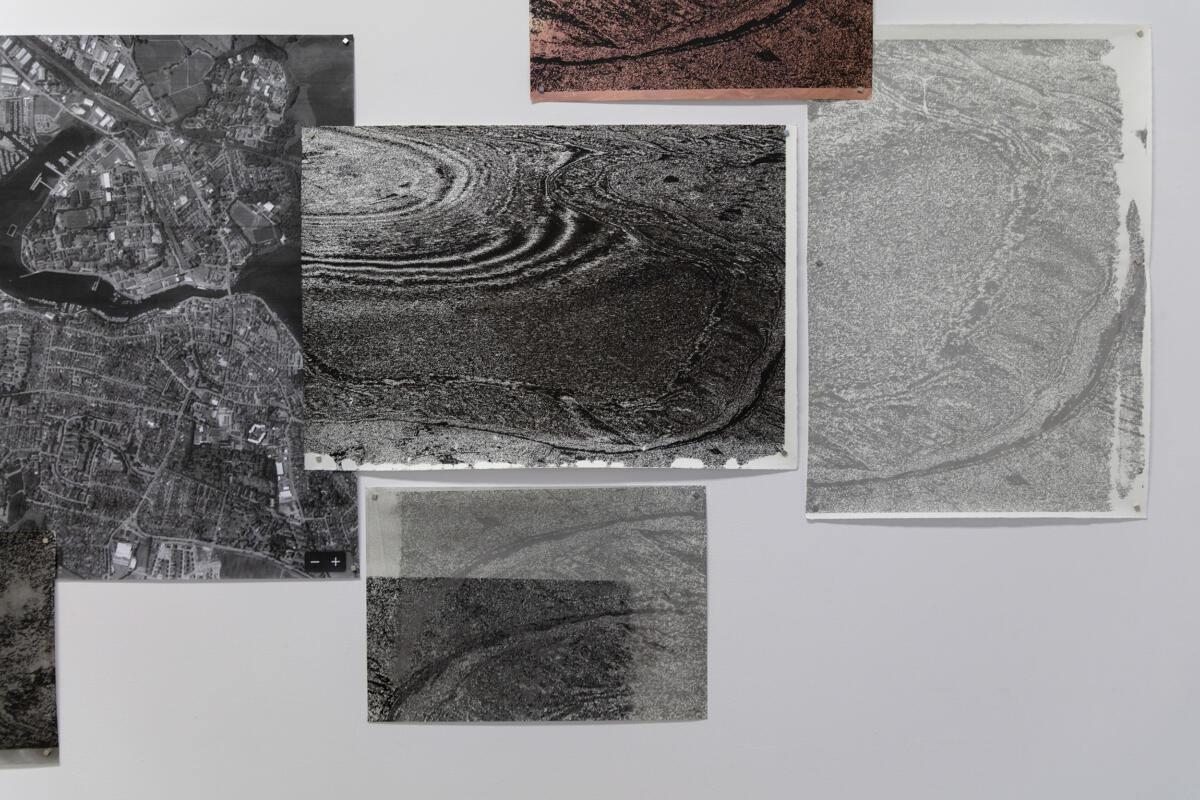

She holds up an optical device. It makes the image slightly distorted, enlarged, and yet remote in time, as if it were a memory from a journey. Strange as the outline of a new, insubstantial piece of land. A shift in scale: ripples on the surface, like the concentric circles from a drop of water, they smoothly dissolve and disappear. Another shift: the Baltic Sea. The coordinates 54°04′18″N, 10°50′24″E mark a point the survivors had thought to be a temporary stopover on the way to their homeland, a transit point, a provisional waiting room. From among the almost three thousand waiting, only fifty survive.

Sława Harasymowicz, ‘The Bay’, 2020, Archeology of Photography Foundation, photo: Anna Hornik

The Third One: The Man with His Hands Up

Are all shipwrecks alike? First, the sound. The crack of the hull when the ship hits a rock or a glacier, multiple explosions after the attack of submarine torpedoes, bomber planes, or crackle of a fire in the wheelhouse… Sooner or later, panic breaks out, there is lots of screaming and commotion. A frantic search for lifeboats and escape routes onto the upper decks. To find refuge from the water flooding in. Some simply jump into the sea; they leave white foam and disappear. The massive bulk of the ship slides into the depths of sea. The same old bay looms in the background, all seems quiet on the horizon.

A ship is a placeless place, an immense source of imagination and heterotopia as such. In civilisations without ships, dreams dry up, wrote Michel Foucault. Towards the Thielbek with its broken rudder, towards the Thielbek moored in the Neustadt Bay, the Neuengamme survivors walked a death march and travelled in freight cars. They waited in lines to get on board the ship, together with two hundred camp guards who shared the prisoners’ fate. The Thielbek and the other three ships of the prisoners’ fleet are a space of delusions that allow us to hold onto a belief that everything is under control.

Lush interiors, velvet armchairs, mirrors… These last, in particular, were recalled by the former prisoners as the cruellest. They showed them the truth. The reflections of their cadaverous bodies – the result of months of starvation, physical and emotional damage. The mirrors gave no opportunity to look away.

H.N.5 515 is a sequence of cinematic and photographic frames; an ambiguous (re)construction of possible events.

Sława Harasymowicz, ‘The Bay’, 2020, Archeology of Photography Foundation, photo: Anna Hornik

The Fourth One: The List

– …again, who was Marian?

– …your grandfather’s brother. He was in a concentration camp in Hamburg and at the end of the war the Germans loaded them on a mined ship and that’s how it ended.

Sława Harasymowicz, Speech Atrophy (2017)

Who was Marian? A prisoner of the Neuengamme concentration camp in Hamburg, in a district that had had no school the decade before. Employed at a camp workshop, putting together miniature parts for the German anti air-raid rockets. 12.5 x 42 metres – that was the size of the workshop barrack constructed by the Deutsche Messapparate GmbH (Messap) company in an area to the north of the SS camp. Rows of desks in the barracks of the Messap commando served as laboratory stations for producing time-delay fuses for grenades, tiny detonators and timers. Mechanisms made with the precision of a watchmaker. The work required skill; it was painstaking. This association is far from accidental: in the summer of 1942, the camp commando set up collaboration with watchmakers from Schwarzwald – the Junghans company. A hand-held magnifying glass and a pair of tweezers, faint light glowing from the table lamp. Weary eyes, throbbing headaches. The images overlap, they blur. The eyes cannot stand the strain.

Next to the Messap commando was a workshop run by Carl Jastram’s company from Hamburg, which specialised in producing engines. Apart from repair and maintenance, prisoners adjusted and produced parts for submarine torpedoes. Precision and exactitude prevailed here too, but these were measured on a different scale. On the lists – neither names nor numbers. Exacting work does not tolerate surnames. Instead, there are terms to describe the metal alloys, elements, substances and parts of the mechanisms installed; all illegible and disorganised, like manufacturing waste.

Sława Harasymowicz, ‘The Bay’, 2020, Archeology of Photography Foundation, photo: Anna Hornik

The Fifth One: How to Assess Bomb Damage

A flight tracker – like a fortune teller’s crystal ball or a small spheroidal object on a desk, an object containing scraps of the world. Will it pin down the target precisely enough? Will it show the exact location? Will it provide reliable data? The power of optical devices, placed in human hands. These shifts in scale and rapid spatial jumps – from a view of the Baltic Sea to the table in the room – free individual images of their unambiguity, furnish them with excess. Photographs of imprecise repetitions.

On 3 May 1945, British Hawker Typhoon bombers sank three ships: the Cap Arcona, the Deutschland and the Thielbek. How could such a mistake have happened? Who gave the order to fire, mistaking the prisoners’ fleet for German military transporters?

Excessive contact with imprecise repetitions, exercises in which the connection between the perceptual data and the name comes loose or disappears, overtax the eye of the observer. And lead their sight astray. Because what is this light circle in the lower right-hand corner – the water of the sea observed from too close? From the crystal ball, the hand-held glass, or the face of the clock to astral bodies… From the tiniest to the largest components of this world.

The text accompanies the exhibition The Bay by Sława Harasymowicz, curated by Anna Hornik and Marta Przybyło at Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw.

Imprint

| Artist | Sława Harasymowicz |

| Exhibition | The Bay |

| Place / venue | Archeology of Photography Foundation, Warsaw, Poland |

| Dates | 19 November 2020 – 30 January 2021 |

| Curated by | Anna Hornik, Marta Przybyło |

| Website | faf.org.pl/ |

| Index | Anna Hornik Fundacja Archeologia Fotografii Magdalena Ziółkowska Marta Przybyło Sława Harasymowicz |