The idea was born

In spring 2019 the Tartu Art Museum approached the curators of Silver Girls with encouragement to curate a project on their premises, in the third floor exhibition halls of the peculiar leaning building. We were offered a blank canvas with no strict thematic frame, which we filled with the idea of an artistic project that would both actualise aspects of the history of photography and question the way we perceived truth presented to us both through narratives written by historians and through images supposedly mirroring the existing world.

The first impulse for Silver Girls was the project (In)Visible Authors, curated by Šelda Puķīte in collaboration with the Latvian Museum of Photography for the Riga Photography Biennial 2020 programme.[1] There is a lack of focused, goal-driven research into the history of women photographers in Latvia, not to mention the lack of exhibitions and publications. Which left no other choice than to ask for the reasons behind the gender disparities in representation and the ignorance of historians that has led to the need for women’s history and theory movements. The burning question was if there just were no significant women agents in the history of photography or whether the writing of the history had involved eliminating unwanted elements.

Taking into consideration the connected history of Latvia and Estonia, as well as the fact that Estonians have already done some research and held a few exhibitions dedicated to the topic, it seemed logical that the Tartu exhibition should represent both geographical regions. Nevertheless, the development of the idea did not stop at making a representational and historical show. We didn’t want to reconstruct some abstract objective truth but present an unapologetic point of view from the present perspective.

To enhance the contemplation of the lost, the found and the retold, we chose three contemporary artists to tell their stories about certain moments and people from the past. History is made out of puzzles of the lost and found, the destroyed and recovered, the denied and accepted, making our present history a mirror we choose to look into.

Photocraphy courses of Latvian Photographic Society. Photo salon Klio. 1920s. From the collection of the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation

First milestones in research

The case study of Latvia

Until recently there have not been any extensive attempts to look into the history of early women photographers in Latvia, not to mention an exhibition or a book project, which makes the available material very scattered. Part of the problem is that since the 1980s, when the first book dedicated to the history of photography in Latvia was published,[2] no updated editions have come out. Published books dedicated to photography have been mostly monographs of particular authors or topical, i.e. related to some historical style or period. The most significant new work on early 20th century photography is a chapter in the relatively recently published book on the art history of Latvia.[3] There we can find a small paragraph about Lūcija Alutis-Kreicberga, who was the only woman photographer in this book whose work has been reproduced.[4]

The 1980s book Art Photography in Latvia includes information about the formation of the Latvian Photographic Society (LPS),[5] which became an important institution for the local photography community. From the very beginning, it included many women photographers, which led to the formation of the Women Members’ Committee in 1914. LPS issued publications to educate the public about the medium, organised exhibitions and mediated the participation of Latvian photographers in international exhibitions. They also organised photo courses, which became an important learning base for numerous women wanting to enter the field. Considering the available materials, it seems that at least inside the photographic community gender prejudice was not present or was not very strong, as women seemed to get a lot of opportunities not just to become members and attend courses, but also to participate in the Society’s exhibitions both in Latvia and abroad.

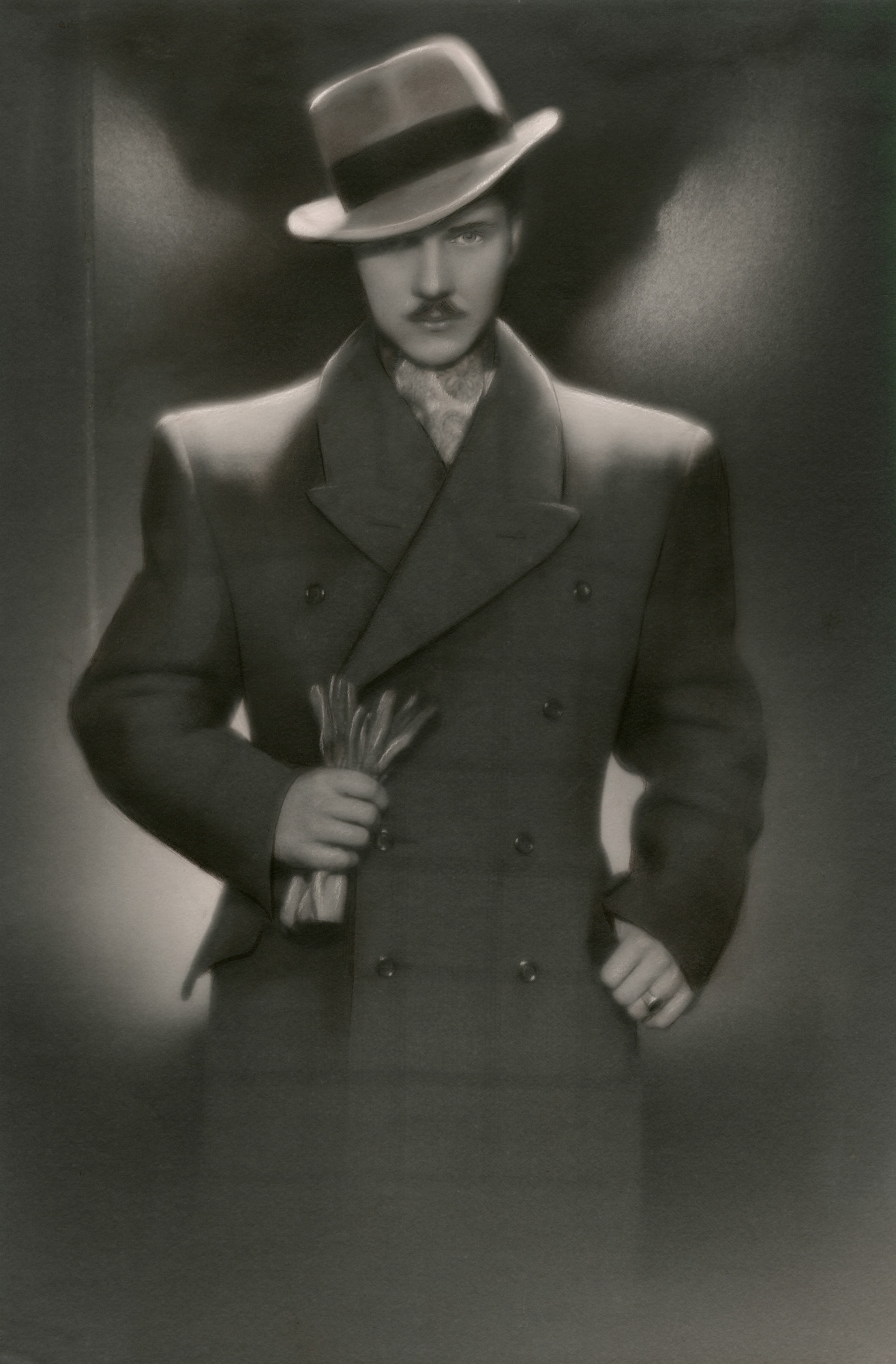

Lūcija Alutis-Kreicberga. Man in a coat and a hat. 1920s–1930s. Retouched silver gelatin print. From the collection of the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation

A crucial figure in writing articles about such early Latvian women photographers as Lūcija Alutis-Kreicberga, Antonija Heniņa, Emīlija Mergupe and Marta Pļaviņa is the photographer and photo historian Pēteris Korsaks, who has published several articles in newspapers and magazines. There were even a few special portrait articles of photographers as part of the celebration of photography’s 150th birthday, published in 1989 in the magazine Lauku Dzīve. Emīlija Mergupe was covered in a short chapter in a book dedicated to the cultural history of her birthplace.[6] In the case of Kreicberga, a fortunate factor was the research dedicated to the Latvian artist Kārlis Padegs (1911–1940), who worked in her salon as a decorator. Through his legacy, hers was also brought to the attention of researchers and the public in general.

Some of the material, mostly prints, was found in museum collections, mainly different photo collections but also archives, where one can find images that are filed as documentations of certain events or portrait photos used for passports. One of the main places to start is the collection of the Latvian Museum of Photography, which holds works by several women photographers. A beautiful collection of Kreicberga’s original prints is in the possession of the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation. Very important sources are regional museums. The most significant regional holder of a collection of women photographer’s images seems to be the Aizkraukle’s Museum of History and Art. One of the most significant parts of their collection in the present context is their hundreds of Marta Pļaviņa’s glass negatives. Finally, there is also the significant private collection of the above-mentioned Pēteris Korsaks, which he built up for decades by gathering images from different people, including relatives of photographers.

Although there have been several attempts to look into the legacy of some early women photographers in Latvia, only after the efforts of the curator Šelda Puķīte in the autumn of 2018 and with support from both the Riga Photography Biennial and the Latvian Museum of Photography, was focused research on early women’s photography history in Latvia launched. As a result, the historian of Latvian Museum of Photography Guna Ševkina has done research dedicated to women photographers who were connected with the region of Aizkraukle, while Šelda Puķīte continues to do research on the topic in general. There is still a lot of work ahead, but hopefully an important precedent for the research has been set.

The case study of Estonia

Estonians too have not paid much attention to the history of their women photographers, but enough has been done to allow us to examine exhibition history rather than archives in order to make our selection of five authors we showcased as the Silver Girls.

The first conscious attempt to draw attention to women photographers was made in 2015 by the Estonian Photography Museum, with the exhibition Out of the Shadow. The First Woman Photographers in Estonia, which was curated by Betty Ester-Väljaots and Merili Reinpalu. The exhibition told the story of four photographers, Evi Lemberg, Anna Kukk, Hilja Riet and Lydia Tarem, of whom the three latter also became part of the Silver Girls exhibition and are featured in this book.

A year before the exhibition in the Photography Museum, the Museum of Hiiumaa opened the show Early Women Photographers of Hiiumaa, which introduced the heritage of two women photographers who had worked on the island: Elisabeth Nurmik and Helene Fendt, of whom the latter became one of our Silver Girls.

The best coverage in terms of exhibitions and research has been on Hilja Riet and Anna Kukk, both of whom worked in the studio of Jaan Riet in Viljandi. Hilja Riet’s postcards were first rediscovered by the legendary photo historian Peeter Tooming, who organised an exhibition of her work in 1993 at the photography gallery Lee in Tallinn. Other exhibitions, organised by the Viljandi Museum and the Kondas Centre in Viljandi, have followed.[7] Anna Kukk’s album was also the subject of an exhibition at the Viljandi Museum.[8] Several articles on the Riets’ heritage have been published in an annual publication called Sakala kalender [Sakala Calendar][9], which contains valuable articles on the history of Viljandi, but has a particularly local reach when it comes to readership. This has an influence on the character of the articles, which seem to be written with readers who are interested in their local history in mind.

Part of the tone of the research is also influenced by the fact that a great deal of the information we have about the authors stems from the memories of family members and from domestic archives. Hilja Riet’s son Kristjan Riet has been an important source. The Riets aren’t an exception: the same holds true for Lydia Tarem, about whose life we know mostly through the recollections of her sister’s daughter Monika Suursoho.[10]

Minna Kaktiņa. Anastasija Skundra and Milda Akmens in dancers’ costumes. 1929. Hand coloured silver gelatine print. From the collection of the Latvian Museum of Photography

The exhibition Out of the Shadow in the Estonian Photography Museum was accompanied by two articles by the photographer Annika Haas in the Estonian photo magazine Positiiv[11], which tell the story of the four photographers of the works in the exhibition, summarising their life stories and to some extent interpreting their heritage in this context. The most comprehensive research article about early Estonian women photographers was published by the photography historian Tõnis Liibek as recently as 2019[12]. With its extensive references, it’s an indispensable source. Olga Dietze, the fifth Estonian showcased as a Silver Girl, has so far been solely the subject of the work of Liibek, who admits that he hasn’t had time to properly research her legacy.

The unretouched history

Taking into consideration the material that we had available, we decided to select ten early women photographers for the exhibition: five from Estonia and five from Latvia. Although the number of the women photographers that we chose to work with seems small, there are very few rediscovered authors whose legacy can be evaluated by their extant works. In many cases the best you get is the name of the photographer and their working location as the only known information. Even with the photographers who have been rediscovered by historians, there has not been sufficient research on their heritage.

Rather than attempting to rewrite the research, the exhibition Silver Girls set out to look at the historical material as part of the contemporary art field. That requires curatorial choices that aren’t in line with those that one would make for an historical exhibition since our goal wasn’t an accurate overview of the authors. Our interest was instead to present them as artists in a contemporary sense.

Although many of the photographers worked in salons with controlled lighting, painted backdrops and props, except for Lūcija Alutis-Kreicberga we did not choose to represent them through this lens. Kreicberga is one of the few photographers (Hilja Riet being another) whose original enlargements that she made during her lifetime for an exhibition have been preserved. She left Latvia as a refugee during World War II, her glass plate negatives were destroyed and, besides these unique pictures, her legacy is formed mostly by postcard format images of celebrities that have survived because people have collected them.

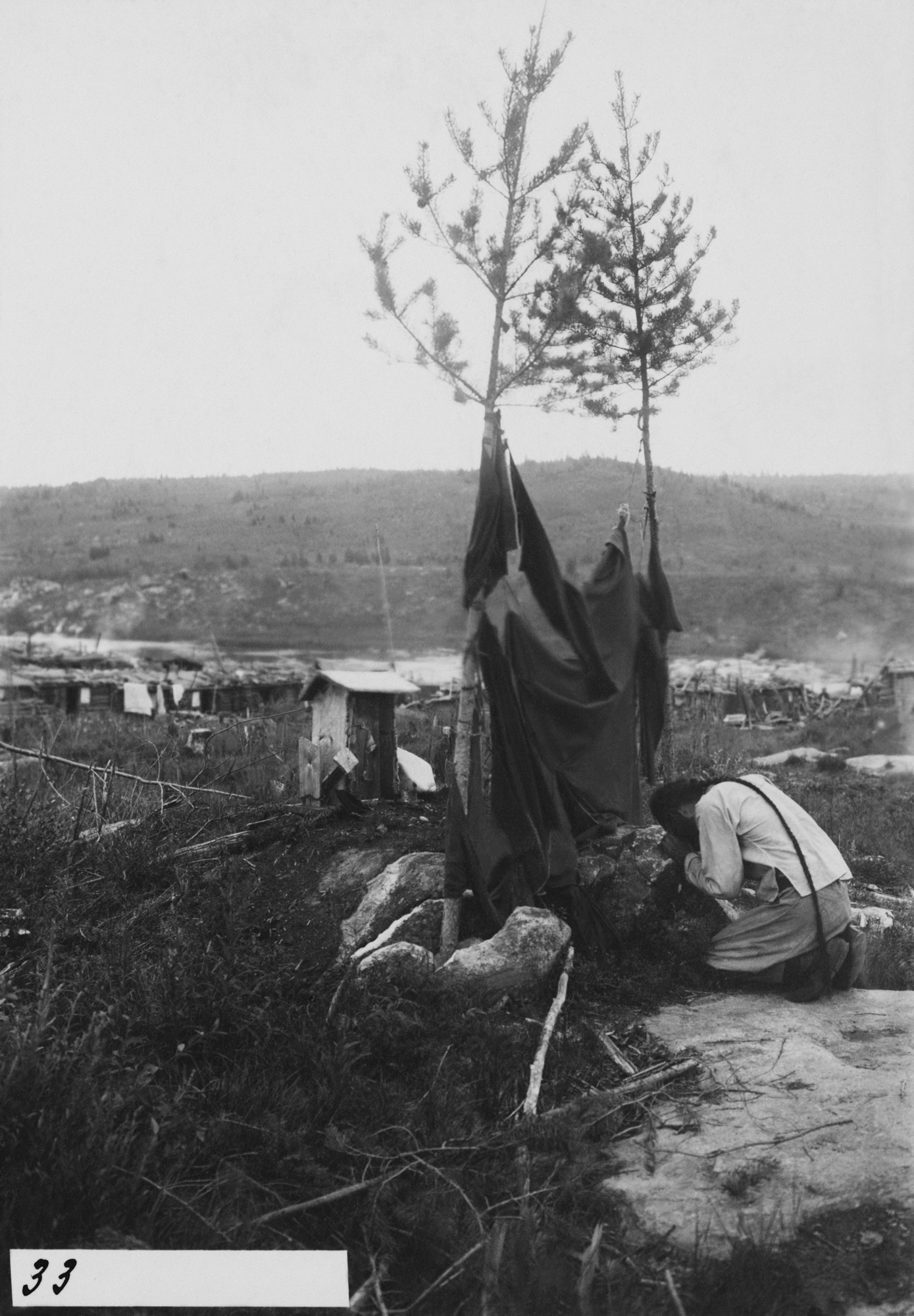

Anna Kukk. Photos and hand written comments from the album Gold Panning. 1912. Silver gelatine prints. From the collection of the Museum of Viljandi

In choosing works for the exhibition, we weren’t looking for single images; our goal was to curate series. Some of them were selected from pre-existing collections, such as the Estonian photographer Anna Kukk’s exotic album of Zeya gold washers and Hilja Riet’s numerous postcards with flower compositions. There is also Lidya Tarem, a highly professional studio photographer whose personal album contains pages with self-portraits taken in front of a mirror. Her playful photos, which to a certain extent resemble today’s selfies, have something fresh and honest about them since refinement was not a part of the method or the goal.

The curators probably went furthest with their personal interpretations when choosing works from Helene Fendt’s heritage. Taking landscape photos for postcards she would often incorporate towers into her compositions, which were quite often lighthouses, since she lived on an island. But, unless you put these images together in the style of the German conceptualists Bernd and Hilla Becher,[13] you might not notice their repetitive, almost typographical character.

Antonija Heniņa and Minna Katktiņa were salon owners. But as their photo heritage is very limited, instead of their studio work we decided to focus on other, more interesting examples from their collections, including landscapes and captured episodes from rural life. A mixed selection was also made from the vast heritage of Marta Pļaviņa. Her large number of works allowed us to choose particularly fascinating and weirdly beautiful photos made in her simple salon, as well as photos in nature mimicking both magazine images of women at leisure and some 19th century paintings where the figurine is a staging element in the landscape.

One case where the choice was very limited although the photographer had a successful career is that of Emīlija Mergupe. There is almost nothing left of her heritage but she seemed too important to ignore. Once celebrated as a landscape photographer, all that’s left today are images that she made of her birthplace and relatives. In addition, we do have numerous portraits of her as a modern woman of the 20th century.

The only non-professional in the group was Olga Dietze, who seemed to take her hobby very seriously but never pursued a professional career. Again deviating from the historically obvious, we did not choose any of her Tartu cityscapes nor the first known photo of Estonian peasants in front of a farmhouse. Instead, we went for the atmospheric images of women at leisure: they seem to capture the fading era of the bourgeoisie, carrying a spirit of freedom, and of the emancipation of women.

Helene and Paul Fendt near Kõpu lighthouse. Unknown photographer. 1930s. Silver gelatine print. From the collection of the Museum of Hiiumaa

Manuscripts don’t burn

Women’s history is gaining more and more popularity in the Baltic states[14] and besides the political reasons to pursue this kind of research, one of its attractions definitely is that there is a lot of material that has not been investigated before, making it a gold mine for any historian. One could even say that the lack of material instead of being an obstacle is a spring board. This is something that is made clear by the works of three contemporary artists who were invited to provide works to accompany the selection of historical material.

The Danish artist Nanna Debois Buhl’s installation Stellar Spectra (2020), which is dedicated to the astronomer and spectral photography pioneer Margaret Huggins, is a quite classic artistic approach to historical material. Rather than words, Buhl uses visual language packed into a two-channel video and a curtain installation to convey the importance of Huggins, who was appreciated during her life but whose research in astronomy has been forgotten by history.

Marta Pļaviņa. Woman with flowers. 1920s–1930s. Glass plate negative. From the collection of the Aizkraukle

Elisabeth Tonnard and Sami van Ingen, the other two contemporary artists in the exhibition, aren’t as concerned with the importance of what’s forgotten or lost. They remind us of the literary quote and the cultural fact that manuscripts don’t burn. Paintings from the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin that were destroyed by fire during World War II are by all accounts lost, but they are at the exhibition as part of Tonnard’s artwork and are featured in this book. Sure, physically they have ceased to exist, but their cultural influence hasn’t gotten any weaker. If anything it has grown as is proven by Sami van Ingen’s short film Flame (2018). The work is based on the few preserved minutes of director Teuvo Tulio’s film Silje – Fallen Asleep While Young (1937), all the copies of which were believed to have been lost in a studio fire in 1959, until one film roll was rediscovered in Paris. Although most of it had turned to jelly, van Ingen edited, working with the few retrievable minutes of the original, and created a new film that is paradoxically the way in which we will from now on perceive the intentions of the original film’s director.

The mirror, a crucial element in image making, serves as the central metaphor of this project. It has falsely been perceived as reflecting the world as it is. But it turns out to reflect the world as we want to see it. When one looks at the historical paths of photography and women’s involvement in it, it’s significant how this medium’s development and growth in popularity developed in sync with the women’s emancipation movement. Democratisation of the arts, as photography was perceived, makes it almost a political tool in the hands of women. Today, in the “post-truth” era, when feminism is on its fourth wave, this project serves as another looking glass for glancing at the future through the past.

[1] The Riga Photography Biennial 2020 exhibition (In)Visible Authors originally was planned to take place 4.05.–17.05.2020 in advertisement stands of Riga public transport stops, but due to the quarantine restrictions caused by the worldwide coronavirus pandemic it was moved to September (7.09.–20.09.2020).

[2] Latvijas fotomāksla. Vēsture un mūsdienas. Compiled by Pēteris Zeile. Riga. Liesma. 1985.

[3] Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa. “Fotomāksla”. Latvijas mākslas vēsture V. 1915–1940. Compiled by Eduards Kļaviņš. Riga. Institute of Art History of the Latvian Academy of Art; Art History Research Foundation. 2016.

[4] The work reproduced in the book by Lūcija Alutis-Kreicberga is Girl with a Necklace. 1930s. Retouched silver gelatin print. From the collection of the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation.

[5] The Latvian Photographic Society was founded in 1906.

[6] Pēteris Korsaks. “Mālpils fotogrāfi – sava laika un vides hronisti 20. gs. 1. pusē”. Kultūrvēstures avoti un Mālpils novads. Compiled by Ieva Pauloviča. Mālpils. Latvijas Zinātņu akadēmija. 2016.

[7] An overview of Hilja Riet’s exhibitions can be found in Tiina Parre’s article Hilja Rieti kunstilised postkaardid, published in Viljandi Muuseumi aastaraamat 2008. Viljandi. Viljandi muuseum. Pp. 44–45. And in “Tuntud ja tundmatu fotograaf Hilja Riet”. Kultuur ja Elu, No. 4, 2008.

[8] Reportaaž kullapesust. Viljandi Museum. 27.03.–28.04.2002.

[9] Vilve Asmer. “Viljandi tuntuim fotograaf”. Sakala kalender. 1990. Pp. 80–83.

Tiina Parre. “Hilja Riet – Viljandi tuntuim naisfotograaf”. Sakala kalender. 2005. P. 91.

Tiina Parre. “Fotograaf Jaan Rieti õppereis Saksamaale 1903. a”. Sakala kalender. 2006. Pp. 183–187.

Tiina Parre. “120 a. fotograaf Anna Kuke sünnist”. Sakala kalender. 2008. Pp. 115–120.

[10] Kristin Aasma. Ühest jõulupildist valgustatud elu. Kultuur ja Elu, No 4, 2006.

[11] Annika Haas. “Meie esimesed naisfotograafid”. Positiiv, No. 23, 2015.

Annika Haas. “Meie esimesed naisfotograafid”. Positiiv, No. 24, 2016.

[12] Tõnis Liibek. “Women with Photo Cameras”. Estonian Press Photography 2019. Tallinn: Estonian Association of Press Photographers. Pp. 146–149.

[13] Bernhard Becher (1931–2007) and Hilla Becher (1934–2015) were German conceptual artists and photographers working as a collaborative duo. They are best known for their extensive series of photographic images, or “typologies”, of industrial buildings and structures, often organised in grids.

[14] It can be linked to the new wave of feminism, which is also present in the Baltic states, and to research-based projects. An example is the exhibition Creating the Self. Emancipating Woman in Estonian and Finnish Art (06.12.2019–26.04.2020) at the Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn and its accompanying conference Women Artists in Baltic and Nordic Museums (5.03.–6.03.2020). There is also the Pallas 100. The Art School and Its Legend exhibition, which featured a special section dedicated to women students (25.05.–27.10.2019). Worth mentioning from Latvia are the Riga Photography Biennial project (In)visible Authors (7.09.–20.09.2020) and Not Yet Written Stories – Women Artists’ Archives Online, a research and exhibition project curated by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, which will take place in the Latvian National Museum of Art in autumn 2020. In Lithuania, the most recent project was the publication of the book Foto Vėros Šleivytės (2020) by the Kupiškis Ethnographic Museum.