![Q&A: Annenstrasse 53, [Graz]](http://blokmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/20210930-ziga-testens-announcement-for-films-for-a-free-palestine-02-1200x900.jpg)

Annenstrasse 53, is an independent exhibition space that exposes (un)learning processes. By dislocating teaching and research from the university (IZK, TU Graz), students, artists, architects, theorists, and practitioners actively work toward a praxis that engages in non-normative critique. It becomes a learning space that asserts the idea of becoming a student – how to learn and how to be learned in all its uncertainty.

By unravelling standardized and oppressive structures that emerged with colonialism, Eurocentrism and Americentrism, forced acculturation, fascism, and capitalism, Annenstrasse 53, conceptualizes and practices exhibiting as a continuous, open-ended process, where cross-reading generates novel thoughts and debates, as something that is thought beyond temporal and spatial closure. Within this flux we position research as an investigative, transformative process for all involved.

Annenstrasse 53, is run by Das Gesellschaftliche Ding. Kunst, Architektur und Öffentlichkeit and is part of the KUNSTRAUM STEIERMARK fellowship program of Land Steiermark.

Supported by KUNSTRAUM STEIERMARK fellowship program of Land Steiermark; Land Steiermark, Abteilung 9 Kultur, Europa, Sport; the City of Graz, Kulturamt; and steirischer herbst ’21

Annenstrasse 53, 8020 Graz

annenstrasse53@gmail.com

Dzana Ajanovic

Rose-Anne Gush

Budour Khalil

Anousheh Kehar

Simon Oberhofer

Philipp Sattler

Milica Tomić

Was it a good idea?

M Oh yes, it was! And I think this is a perfect question to look back and see how Annenstrasse 53, is actually a perfect example and result of “concrete analysis of a concrete situation”(Lenin). We started Annenstrasse 53, exhibiting space in an absolutely uncertain and precarious situation. The idea was born during the pandemic, the impossibility of exposure, non-existence of public space and the beginning of disintegration of society, in the time of societal collapse. And empty pockets. This situation provoked us to examine the motives of labour and work in art in relation to exhibiting, and of course, the representation in art, by opening the space for the unrepresentable. We have been dealing with this in our courses at IZK for years, and suddenly there was an opportunity to face the bare reality through our praxis within the context in which we find ourselves. Anousheh Kehar discovered and “launched” this space to exhibit student’s work at the end of the semester during the lockdown. The space was in an adaptation phase, as one of the spaces of the landscape design ‘Studio Boden’. We could use it just for this particular event. We kept the space closed, these large windows used as screens, exposed at the busiest street of Graz inhabited mostly by migrants and many passengers who arrive in Graz, passers-by heading to the city from the train station. Students’ video works curated by Anousheh attracted a lot of attention, not only from passers-by but also from the residents of nearby buildings who started discussing, commenting and asking about students’ works. That moment was something extraordinary. And soon, Philipp Sattler and I decided to find a way to inhabit the space by working together with Simon Oberhofer as IZK collective and students, even though there was no financial basis at all. This desire to start a space that would allow us to collectively reflect our praxis, working with students while facing the void and thinking collectively how to present ideas, theoretical work and concepts that mostly remain behind the walls of art studios and universities. So that moment of growing collective while facing real, concrete current financial, political and social conditions to examine difficult subjects; and not being afraid of concrete touch with reality that might show inadequacy, sometimes leading to the incongruity of thoughts and actions is fundamental to our praxis.(also answers question 2.)

A, B Yes! Coming together, and bringing people together. Annennstrasse 53, functioned simultaneously as a space of tension and comfort, where we gathered in conversations around critical topics which connect to Graz but also extend outside of it.

P Yes. As it opens a room of possibilities, for the creation of a discourse and culture that seemed missing and also allows for a new mental space of thinking to grow. It impacts both the collective but also the individual praxis of people involved. And brings constant challenges both in relation of the space with the city and society and its regulations, rules and affordances, but also in ways of organising a structure that allows the space to become operational in any sense.

S For me, it was a necessary step in this day and age for an (educational) institution to seek more publicness.

Who/what has held you up?

A, B People. Navigating what it means to work collectively.

R-A What does it mean to work collectively? Any kind of collectively organised project invokes working together and this seems to bring its pair, working apart, like proximity and distance, passion and indifference, compassion and conflict – are they the right opposites? And yet, I believe that behind indifference or rejection — someone rejects the group, or the group ostracises someone — there is fear of loss, vulnerability and risk, on all sides. I wish for more care and tenderness, and more self reflection within our collective work, which is also the work of building. If we take unlearning seriously, it also has to occur on emotional levels as well.

P Also trust. Trust in people to be there, trust to find help, but also developing the trust to actually ask for help. The process of becoming more than one is a struggle, but it is a pleasant one, as you can see what this struggle brings to the table and what conversations are created through giving space to this struggle of collectivity.

S In educational structures or institutions, what we are doing here is not foreseen. So, the challenge has been to navigate and create this from an inexistent structure.

Is there a limit?

R-A Emotional and physical capacity.

M Financial constraints are always a big issue and problem, but also motivation and resistance to the given.

P Time. Both to digest, and bring forth. But also space as in space to breathe in the cycles of funding, production, administration, funding. This time-space relation is expanding with the group of people becoming part of the project. It is actually becoming better and better the more it spirals out.

S If you keep the structure open and nimble there are no limits. One also needs an open mind.

A, B We felt at times that we were confronted with limits, but then it became a question of how to work with them and through them.

What do you need?

R-A Commitment. Care. Forgiveness. What does it mean to care for people and objects together? – we also reached for Azoulay here, and I think this idea is central to this project. Yet, I ask if we are good enough at care.

S I think the backbone of any endeavor of this kind is healthy communication with mutual respect and appreciation.

A I love what Rose-Anne and Simon have expressed here.

What has been given and what do you take?

A, B Smallness, the intimacy of Graz, this intimacy fostering new formings.

M Political context of Graz.

R-A We started Annenstrasse 53, just over a year ago, first with a work by a student, Lorenzo Sacchi that was made during the first phase of the pandemic. Sacchi subjected a flag, the symbol of assigned identity to the chemicals within the photographic processes without fixing them, and then with the first sequence of the Opening Statement. It was Milica’s idea to introduce sequencing into the program as a way to both add a montage aspect, to see exhibiting in a filmic structure and to express the interminability of this kind of exhibiting. I see this in some sense analogously to what Freud expresses in his (late) essay from 1937, “Analysis terminable and interminable” where he describes the impossibility of a cure within the therapeutic process, because of potential psychic resistances. I see the proposition made by Milica, with Dubravka Sekulic, of a kind of interminable process within the exhibiting space as somehow analogous. The first sequence of the Opening Statement was a conversation that took place between Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Wayne Modest and those of us working at IZK. We were reading Potential History, Unlearning Imperialism; we were also thinking with the concept of ‘unlearning’ within our teaching. Anousheh had also introduced this to BA students at IZK. In my view, the Opening Statement was intended to really bring the whole history of exhibiting into connection with the history of imperialism. I want to recall the first question that Wayne Modest posed to Azoulay. It was about complicity, our complicity within the regime of imperial formation, and in this sense, how we are as much part of the social problem as we can be part of any solution. We started off with this assumed complicity, while asking what can we do, how can we act, in the sense of “what is to be done?”. I found Azoulay’s response very useful. She said, we are born into a world where our complicity is being extracted from us on a daily basis, and a museum makes this deeply visible. We are not a museum, but rather the opposite, a small exhibiting space, yet a space where we engage with these questions. Addressing this aspect of visibility or legibility is to be in the process of unlearning. We have to unlearn the idea that we are ever not part of the problem. Azoulay also asks how we unlearn imperialism? How do we unlearn our assigned identities, this in itself can take years to unlearn. The other facet that she brings, is the directive that we must also unlearn our professional selves. This means that we should create a failure of professionalism and expertise. I have to say that with our project I embrace this. If we take this seriously then a certain pressure is lifted from us and we can operate less formally. Many things don’t matter, and we can attempt to cultivate a more interesting culture here in Graz that is outside of the stuffiness of general institutionalised culture. Another moment when I saw the beautiful breakdown of professionalism was during a poetry reading and discussion that came out of a course at IZK where I had worked with students on a collaboratively written script. I organised Poetics of Unlearning with my friend Christina Chalmers. We invited Momtaza Mehri and Myung Mi Kim. The intention was to bring poetry into architecture education while seeing poetry as a mode or form that has the capacity to bring together thinking, feeling and critique, which are needed for any notion of unlearning, since it cannot simply happen intellectually. During this event Myung Mi Kim was reading from her recent work, Civil Bound which explores how language is an active force in perpetuating injustice (she looks at ecology, capitalism, military powers and land ownership, imperialism and colonization) and how language is itself a binding force, in both oppressive and liberating ways. While she was reading, she lost the Zoom meeting. We were in silence for 15 minutes. This was a perfect example of the kind of fragility of communication during the pandemic, and it brought all of our professionalism into question, as we had no idea if that silence was part of the poem — her work engages with the blank page with a form of austerity — or if she was lost.

B This moment also brought out our compassion. It brought out our care. We were waiting patiently, and wandering, for 15 minutes.

S I think a beautiful space has been activated.

Is it sustainable?

A, B Conceptually, yes. The open-ended exhibition is not limited to a topic – instead, to the idea of unlearning and relearning. This generates organic movement, forming, and reforming.

S Of course.

What is the shape?

A, B Imaginary and encompassing. The exhibition has an opening but expects no closure. Constellations are formed within it. From each constellation, traces are left and take part in the constellation that follows. The shape grows out from this ‘opening’. There is an idea of flux here and it moves in time, but not in a linear way; it disperses in all directions, moves forward but also looks back in a process of self-reflection. Sometimes it appears simultaneously in different spaces; this happened through collaborations with institutions, exhibitions and collectives such as the IZK, steirischer herbst, collective rewilding and the exhibition Land, Property, and Commons in Semmering. When we meet, read and work at A53, we are surrounded by the potential which grows out of the works and ideas in space, and of our interactions with them and around them. This informs the transformation of the flux, which in turn influences interactions and activities in the space. It is always this organic movement between the two. The open-ended concept of exhibiting – with an opening but no end – is reflected with the comma added to Annenstrasse 53, by graphic designer and artist Ziga Testen.

M Distinguishing between the traditional concept of an Exhibition and Exhibiting…

Does it fit?

A, B Sometimes, it does. If we think about its location – does it fit in Graz? In Annenstrasse? Or if it fits in the art world? I don’t know if it needs to fit. It does bring in certain contradictions. We moved into this changing street, changing neighbourhood in Graz. What are we feeding?

S Yes.

M How do we (and do we?) counter and oppose the gentrification process of Annenstrasse?

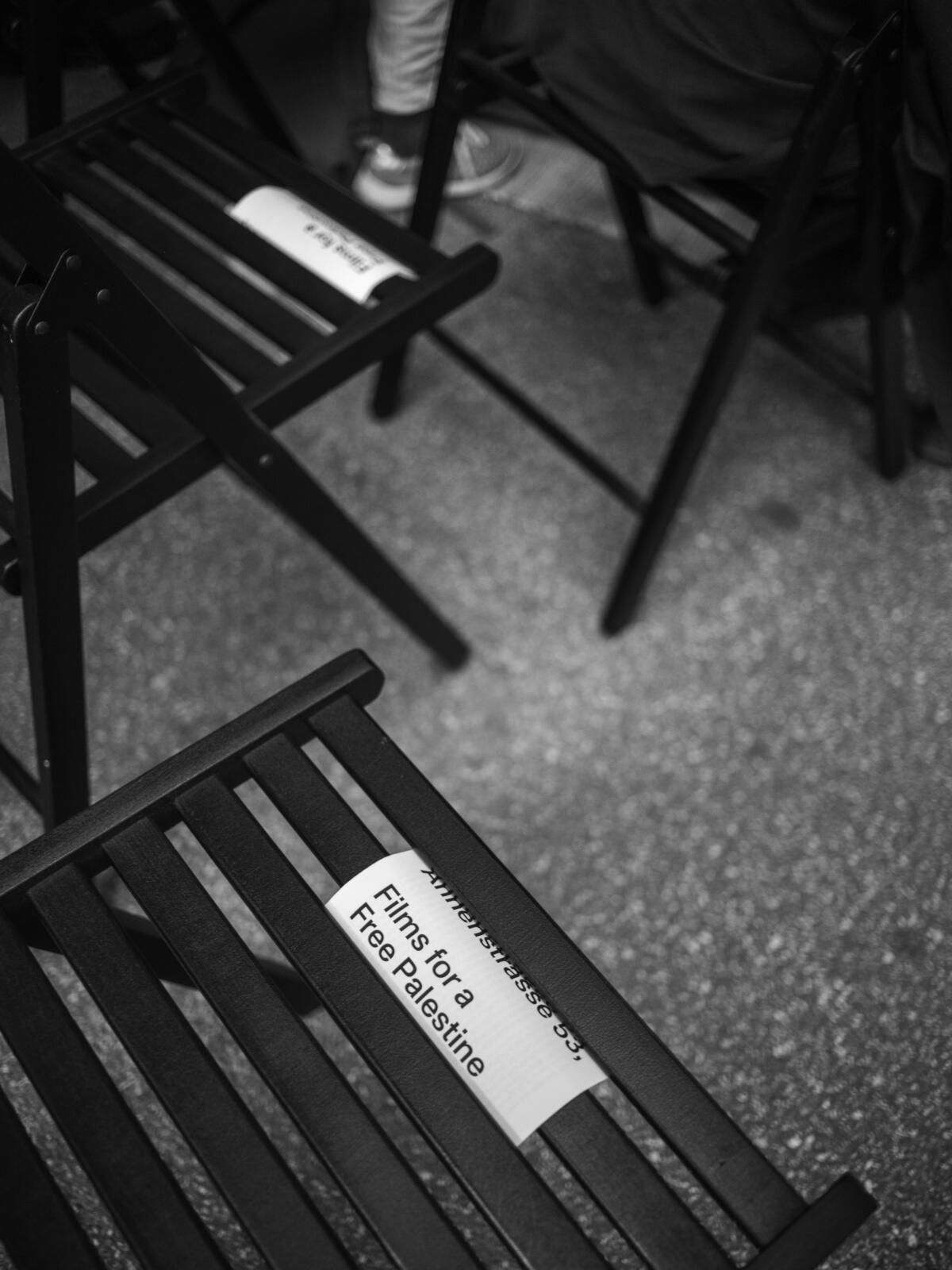

R-A Another moment or sentiment that I take from Azoulay into this project is the idea that we have no right to be satisfied with any of our projects. They are all, simply, attempts to do something and they are all insufficient. She says, until the world is 100% decolonised, we have no right to be proud. I take this provocation seriously, that this kind of project is simply an attempt to experiment and think through the contradictions that we live within, with the horizon being a shared world. In this sense it should not fit, and we will be successful only if we fail. An example we can discuss concretely was our contribution to steirischer herbst 2021. We worked with my friend Daniella Sheir who founded the feminist film journal Another Gaze. In May 2021 she also hosted a film programme, For a Free Palestine Films by Palestinian Women, on the associated screening platform, Another Screen. Then, the films were freely accessible for a month and the money raised (through donations) was sent to organisations in Gaza. At the same time, Anousheh organised a meeting with Budour and myself where she proposed that we work together to bring this issue to the foreground in Austria, because of how it is treated as taboo within the society. We came together under “Even Its Name” with the purpose of organising a culture that breaks the silence on Palestine, and this was how our screening project Free Cinema, or Films for a Free Palestine was born. We hosted Shreir’s programme in Graz, bringing attention to how Austria’s guilt management feeds broader social problems.

Future or Past?

R-A I think an ongoing commitment within our practice(s) is the investigation into history, memorialisation, violence, disavowal. Our particular location: Austria, a country which has survived on the disavowal of its perpetrating role in the Holocaust also necessitates this kind of archeological investigation into the past, but we try to expand this to see it on a global scale. We address these kinds of discursive questions in our reading group as well. If we look back again, Wayne Modest described potential history as a history which was foreclosed by imperial formation. This also becomes part of what we think of when we work at A53,. I want to recall Azoulay who said that she is against “the future”; she is afraid of ideas of the future because they are about crafting the world, this is what architects do and many of us are deeply connected to this discipline. Instead of the future, she talks about returning and reversing, proposing the option of joining with (sometimes foreclosed) forces from the past. I see this in relation to “history from below” projects, like those of Silvia Federici, Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker. But such histories and forces need to be excavated or unearthed, they need to be found. Perhaps in Austria, this takes on a different meaning, and necessarily one that expands our geographical parameters.

S Future. As a photographer I am only interested in the future because everything else I do revolves around the past.

Kin?

A, B Reading together, coming together around food, making a different culture, thinking about solidarity.

What do you measure?

A, B Even though it is not measurable, in a sense, in this flux – with self-reflection – relations are formed and this is what is measured. Although they are not constant or stable, these relations can be between different things, people, ideas and are sustaining the flux. Self-reflection becomes a tool for measuring but what is being measured is not defined.

S Almost everything, because I am educated as an architect.

R-A Honesty within the contradictions.

Digital or physical?

A, B Relations of the flux change with the digital and/or physical. These mixed lives have densities.

S Physical.

R-A Physical.

Why do you stay?

A, B Hope. This makes me/us hopeful. Hope is sustaining.

B Opening a space, with care, potential, where unexpected things can happen.

R-A It is enriching to work with others on such an open project.

Is it enough?

S No.

R-A It is not enough, and it exists in a fragile balance.

A, B This potential that exists in this impregnated space(works, books, traces)- how much is enough to sustain the space in flux? How long can this potential survive when the space becomes inaccessible, except for looking through the glass?

Imprint

| Photos | Simon Oberhofer |

| Index | Annenstrasse 53 Anousheh Kehar Budour Khalil Dzana Ajanovic Kathryn Zazenski Milica Tomić Off Space Q&A Philipp Sattler Rose-Anne Gush Simon Oberhofer |