On the night of February 24, artist Stas Turina woke up from the loud sounds of explosions. His girlfriend heard them too. So did his neighbors. He then checked his messenger to find out that the war had started. He didn’t clearly remember what followed in the next few days.

Turina says that he had the premonition of the war long ago, maybe a year before. It grew with every month and was reinforced when Putin gathered Russian troops along the border with Ukraine in autumn. It was his second attempt. The Russian president first tried that in April 2021 shortly after Biden won the election. I remember that because Putin withdrew forces only after POTUS called him — a weird way to get attention, we thought.

The feeling of war has been around us since 2014. Keeping in mind that the first Russian invasion happened eight years ago, and “ended” with the annexation of the Crimean peninsula and the informal occupation of the eastern parts of our territories, Ukrainians have either been waiting for the next stage of aggression or shaking off thoughts of it. In January, the shaking off became impossible.

‘We were preparing emergency bags. In January, I started sending booklets to my friends, colleagues, and family with instructions on what to do in case of an emergency,’ Turina said.

Turina and his partner Katya Libkind have not left Kyiv since the escalation began. They are still there. “Katya and I decided to stay. We discussed our red lines and that even if the windows in our house get blown away, we are still staying.”

I don’t know that much about Stas, and what I know is mostly random, sometimes fascinating facts about his bio and his opinions from Facebook posts. He doesn’t have a website ( I’m not sure if he even has a CV either), but his biography and career rightfully allow us to consider him a prominent Ukrainian artist. Awards from top art institutions in Ukraine, the founding of significant art collectives, and curation of the Ukrainian pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale—all these accolades hardly corroborate Stas Turina’s low-brow attitude and underground spirit. What characterizes him more accurately is that he openly expresses his frustration with the art system and his colleagues’ works on Facebook and readily admits if he is wrong. The latter is a rare feature for such a public person.

“I am the kind of person who tends to be hung up on certain things. Focus on them, spin them in my head, reread all the comments, check all the likes…,” Turina explains.

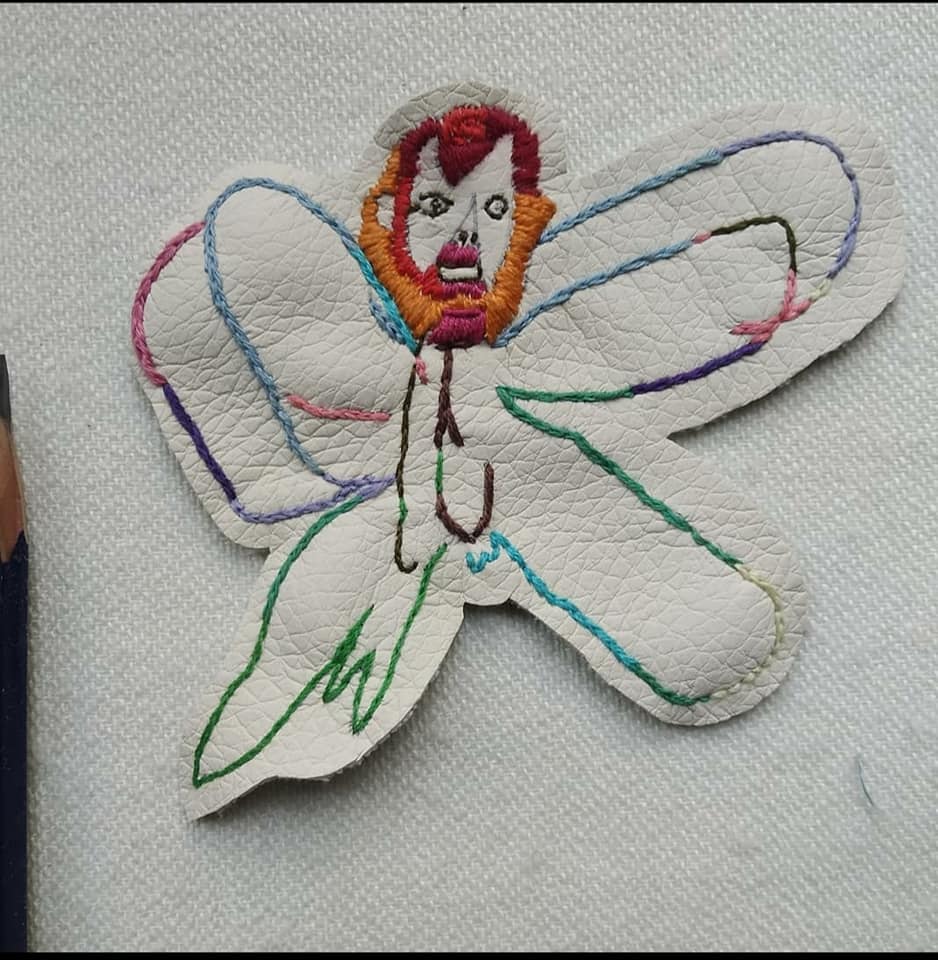

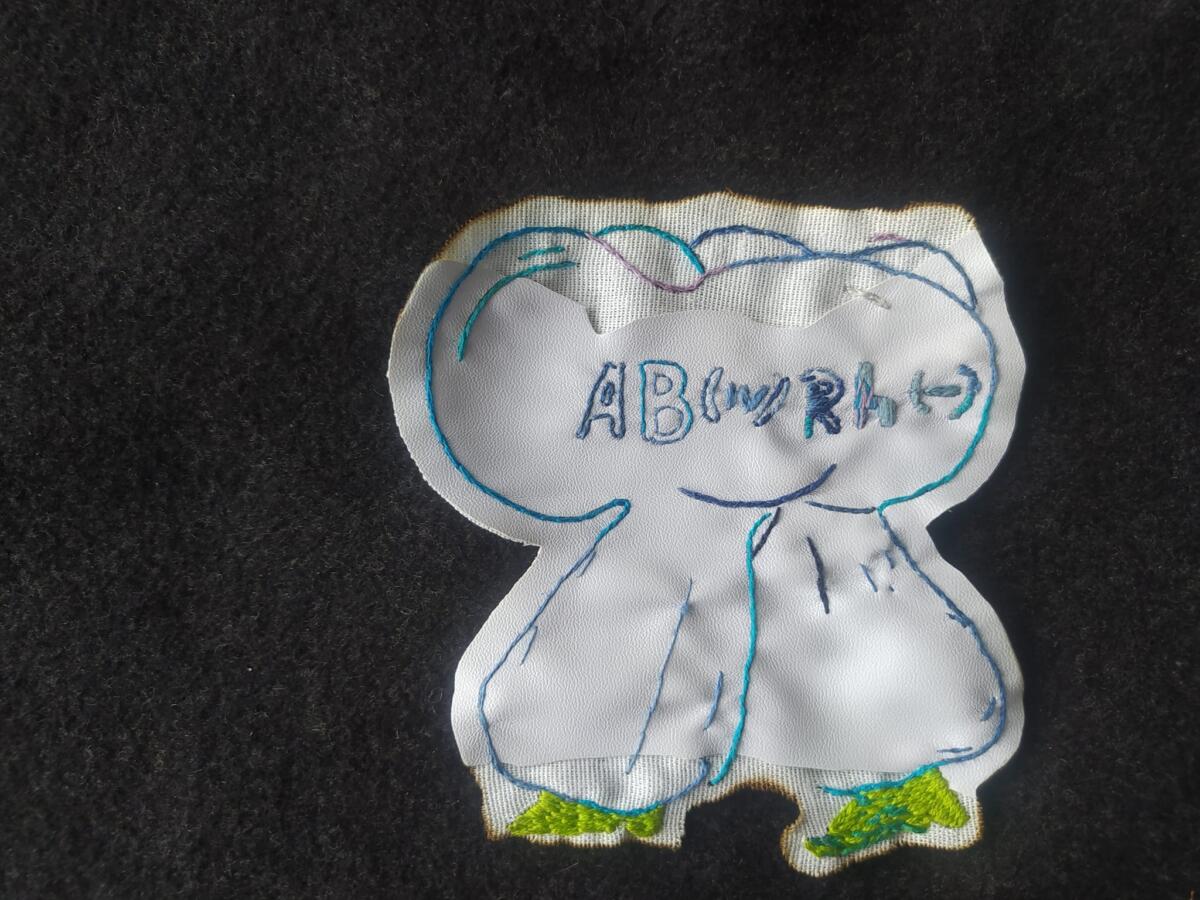

Turina’s works can be characterized as the art of tiny things. His graphics, sculpture, and performances pay attention to the poetry of daily life, minor episodes of reality, and the otherwise unnoticeable. For two years, he’s been creating butterfly patches—amorphous pieces of leather embroidered with unpredictable patterns. It is an homage to the dead underground artist Yan Metelyk (‘butterfly’ in Ukrainian), who was known among the hippie community in Ukraine but only made it to the broader audience with the help of Turina’s works.

Unlike contemporary artists who are directly engaged in political and social criticism, Stas Turina talks about politics on the human and less than human scale.

The most crucial aspect of Turina’s practice is connected to Open Group, an art collective that he co-founded in 2012. As follows from the group’s name, other people can temporarily become its members, making it a flexible entity. Open Group researches the relationships between space, communication, and situations. Their works contain a lot of reflections on what we consider art, what defines it, and what constitutes a space for it. In their long-term project The Open Gallery, artists were making galleries in spaces that were unlikely to fit the typical idea of an exhibition site. Actions like creating a gallery space by squatting in a small concrete hub in the middle of the Carpathian mountains, or claiming as a gallery a part of the road that extends to half of the country all contributed to the question of the framing of contemporary art.

But the highest point of Open Group’s conceptuality was their bold project, The Shadow of Dream* Cast Upon Giardini Della Biennale for the 58th Biennale di Venezia, which since its debut, has caused a heated discussion in the Ukrainian cultural community. Dream, a literal translation of Mriya—a Ukrainian aircraft, the biggest in the world, was planned to fly over the Giardini, dropping a shadow over it. Bearing an important piece of cargo—an SD card with all the Ukrainian artists (1143 artists submitted their applications to the open call organized by the curators to become a part of the leading international art exhibition), the plane was intended as a symbol of the Ukrainian dream to become recognized as a part of the international art community, even if only for a few minutes.

The SD-card with the artists of The Shadow of Dream* Cast Upon Giardini Della Biennale. Photo courtesy: http://open-group.org.ua/

Mriya never flew over the Giardini. Moreover, it was destroyed by Russian troops in the first days of the war. Ukrainians are still struggling to be noticed and recognized by the world, and now it’s even harder than ever. Stas Turina had to leave Open Group shortly after the Venice project, triggered by the exhausting months of crisis management and public criticism.

“I’m not among those who rush to the frontline. […] [But] I told myself that if the president announces that every man should go to the army, I will go.”

Yet, after the war started, Turina and his partner rushed to another crucial frontline—volunteering. He recalls that it was hard to find some spots for volunteers in the first days: Kyiv was full of those willing to help. Finally, he received a call for help from Pavlivka, a large psychiatric hospital. “I thought: bingo! I’ve been interested in working with Pavlivka for a long time. I saw it as a kind of certification training,” Turina said, hinting at his 3-year-long practice of running a workshop for artists with and without Down syndrome called atelienormalno.

Launched in 2018 as a temporary project, atelienormalno transformed into a long-term workshop, residency program, and a series of group and solo exhibitions. Now they work as a collective pushing the idea of inclusion in art and show examples of peer and professionalized approaches to artists with disabilities.

atelienormalno farewell party during the Dacha Diary residency, Beremytske nature park, Chernihiv region, 2021. Courtesy of atelienormalno.

But after February 24, atelienormalno’s activities were temporarily suspended (they have now resumed in a reduced format). Some of the members had to flee, many stayed at home with their parents, waiting.

Turina got to Pavlivka when the situation was chaotic. In one of the buildings where Stas was working, 120 people occupied a space designed for 50 people max, many had to sleep in hallways. “It was like a night train. People with mental diseases, Down syndrome, and severe brain damage. At the same time, Kyiv is being bombed, air-raid alerts [are wailing]. Shock!” Turina, together with local volunteers from the Shevchenkyvskyi district of Kyiv, cared for them, bought food and medical supplies, covered basic physical needs, and assisted the hospital personnel.

“We shaved them. That’s what I’m proud of. In a week, we have shaved more than a hundred people. Hygiene is a key to rehabilitation,” Turina adds.

The train metaphor sounds even more appropriate when Stas starts to describe the patients’ activities in the dispensary. “The options they have to spend time are like those on the train. For various reasons, they have very few personal items. Their leisure is very limited: books, radio, TV.” Turina’s dream is to create a workshop for the patients of Pavlivka where they can make art. He believes they are talented people, so he wants them to develop professionally. “They are on the road. But they are only passengers and are being treated accordingly. [In Russian, the word] ‘passenger’ also has a negative connotation, and many get that kind of attitude. They are neither engine drivers nor conductors, and they cannot live without a driver and a conductor.”

During these 70 days of war, Ukraine has changed a lot. So has Kyiv. The streets are emptier, and people with rifles are everywhere. Unable to return to a previous form of life, the city can’t figure out what the new version of life is either.

Stas Turina keeps volunteering for people with mental disorders. When thinking about how art transforms with war, he has revealed a lot of internal struggles. “Now I have to either help someone or make art. And art, like poetry, has no meaning from my perspective. Probably it is great bravery to say that art for me is the most important thing in my life. Or as important as it was before the war. It is hard to make such a statement right now.”

The war forced Stas to question the constantly changing role of art more often. He openly admits to feeling the fakeness of “art life” now. “It is obvious that something new will come, something different. Everything just can’t remain as it is, we just haven’t all figured it out yet.”

I once again ask Stas why he hasn’t left Kyiv. Wondering what I would do, I try to find out how someone could be eager to stay under shelling. He replies: “It sounds full of pathos, but it is a battle for our freedom. This is my battle, I have been preparing for it for a long time. Morally. Mentally. I watched what Russia has been turning into, what Belarus and Kazakhstan have been turning into. […] This is my home. This is the first house I have rented in my life, the house I am making my own. My archive is here. I work for this city, I have atelienormalno. I deal with issues of responsible citizenship in this city. To flee is essentially to cross out everything I worked on before. I’m not ready for that yet.”

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

Imprint

| Artist | Stas Turina |

| Index | Lisa Korneichuk Stas Turina |