Confidence has become a metric, a unit of measure under late capitalism. Arbitrary and yet powerful, it determines economies that are both tangible and symbolic: stock markets run on confidence, acting with a seesawing optimism and pessimism that is worthy of clinical diagnoses. We also run on confidence, posing for selfies, curating feeds of success and positivity, in a behavior that is clearly no longer that of assurance or conviction, but a labour, skewed towards the appearance of positivity, where photography plays an essential role as evidence or proof. Jia Tolentino has described the programmatic urge to ‘always be optimizing’, tied success and health, and the continual observation, whilst Rosalind Gill and Shani Orgad have tackled confidence head on, describing how it has become positioned as a ‘technology of the self’. Confidence traverses the spheres of finance, labour and sociality, becoming an instrument whose measure or master is unclear. Confidence is treated like currency, but melts into air on a whim, and market traders hold a power that can scarcely be held accountable, confidence seemingly distinctly human, and difficult to cite as evidence.

Our language has been blurred and destabilized. Michiko Kakutani has written that the critique of objectivity has resulted in a hyper-subjective and willfully elusive relation to values, giving rise to the slippery claims of finance capital and new nationalisms. Our language and actions are colonized by this power, and simultaneously economised: Boris Groys has pointed to the fact that our contemporary speech is financial – we “buy” or “don’t buy” ideas; we are “sold” instead of persuaded. It is not surprising therefore that confidence is also possessed: it is treated as if it were able to assume the status of a unit of data. What end does this serve? Who is the measure? And what parameters have they set for us?

Paulius Petraitis, “a black bear walking across a bridge, confidence: 0.6673794 / a squirrel standing on the side of a building, confidence: 0.87864846”. From ‘A man with dark hair and a sunset in the background’, courtesy of the artist

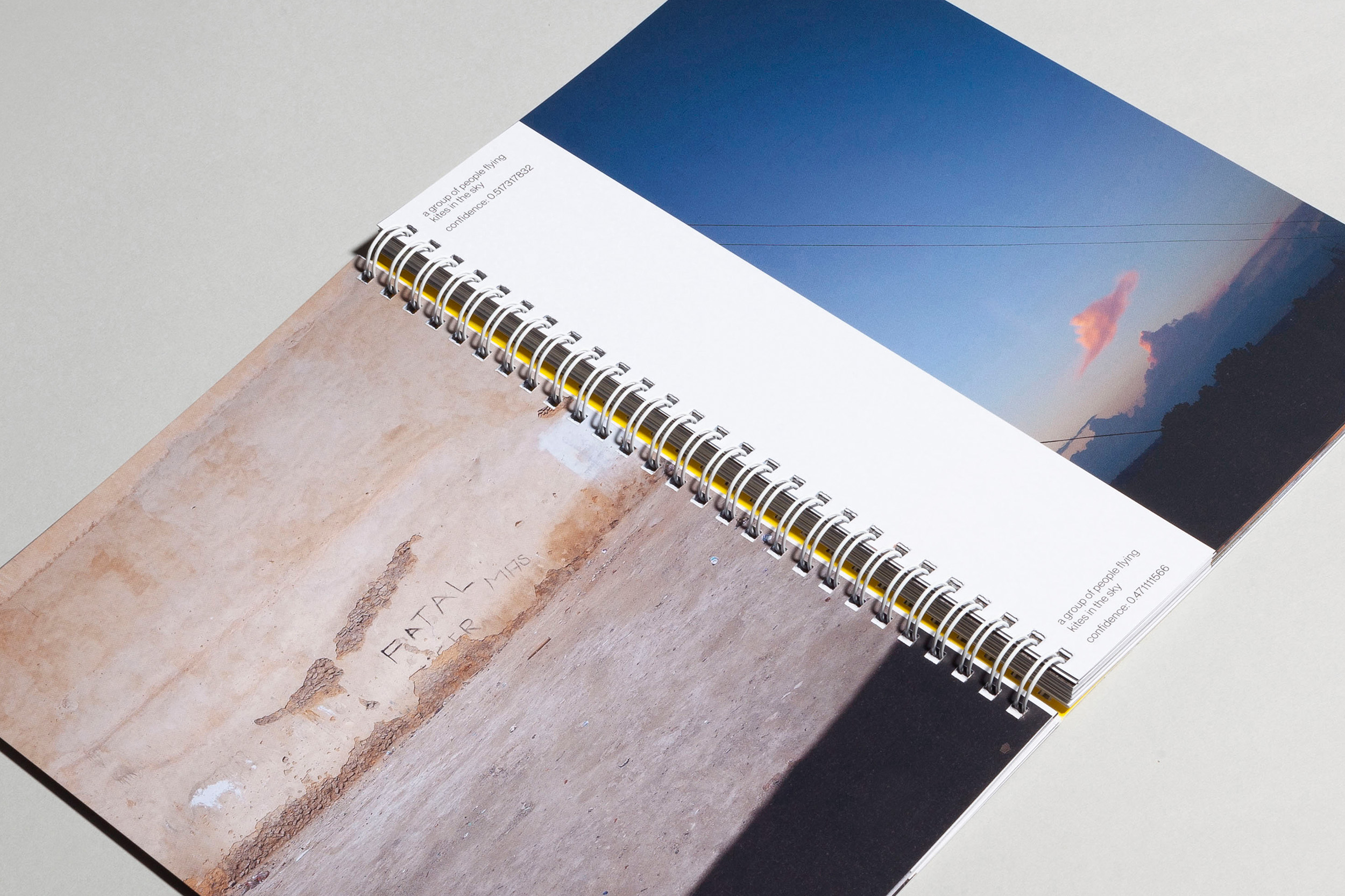

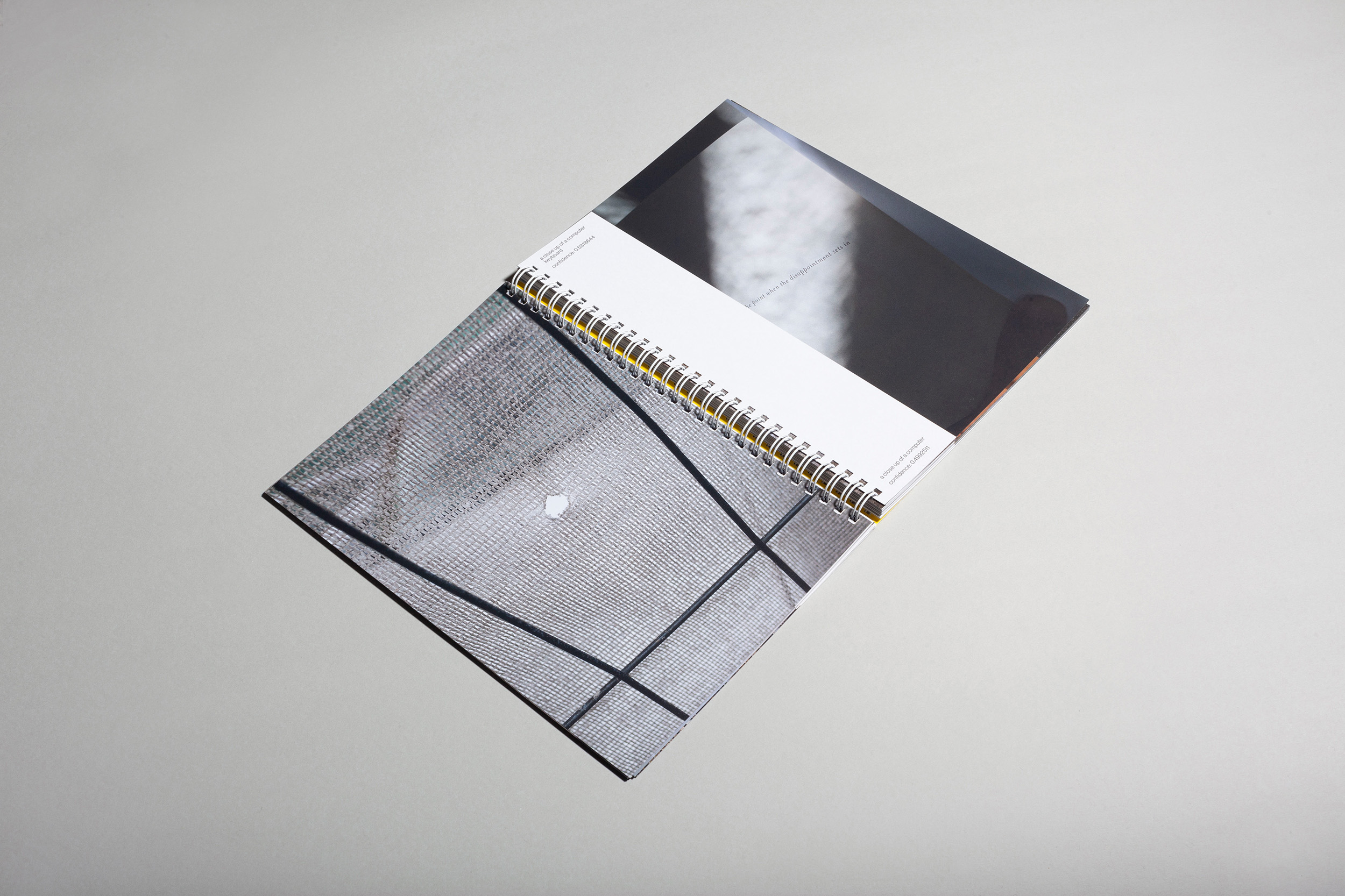

A man with dark hair and a sunset in the background is Paulius Petraitis’ exploration of machine learning and image interpretation software. Processing images taken by the artist through Microsoft’s Azure cloud processing platform, Petraitis tracked his images, their analysis and resulting captions (Azure is a system which names parts of attempts and ventures a more complex descriptive reading), in a project which explores algorithmic confidence and the machinic construction of signification. In the book version of the project, co-published by Six Chairs Books and Lugemik, Petraitis shows the progress and subtle transformations of processing over the project’s three year time period. Returning the images to the same software twice over the course of the project, Petraitis partners his image with initial and later captions, many of which evolve and shift, demonstrating increasing precision whilst displaying transformed confidence values. Some captions remain static, though as the algorithm deploys larger datasets, it usually attempts increasingly sophisticated readings, which Petraitis’ dual captions allow us to witness and assess.

It should not surprise us to find that machine learning too runs on confidence: its use in computing has earlier origins in statistics, in the Confidence Interval, a unit which describes frequency, and calculates the probability of error in small or incomplete datasets. In machine learning processes, confidence describes the precision to which a programmed algorithm believes it has carried out the tasks of identification and categorization. If it can identify, categorize, and put to work its analysed object, a programme demonstrates confidence: in computing, this generates a figure whose integers 0 represent no confidence and 1 complete assurance. Such confidence is dependent upon the dataset, which, to achieve accuracy, must contain a catalogue of the photographable world, in an almost Borgesian encyclopedia of its combinations and arrangements. At the confluence of economic, intersubjective and technical confidence, cloud processing, especially the captioning of photographic images, proposes a reading of the present that reveals the techno-economic programming of everyday life. An encounter with Petraitis’ exploration of this process reveals that meaning does not only slip – it is calibrated and conditioned.

Paulius Petraitis, ‘A man with dark hair and a sunset in the background’, courtesy of the artist

Petraitis’ photographs are many and varied. In the spirit of a sample, amongst his images there are many recognisable objects of mass photography, the observations of the camera as a social tool and plaything: cats, landscapes, parties, food and the body – each are recognisable images that we all, regardless of our critical positioning around the image, find ourselves taking. It is towards these images which machine learning has been trained: datasets, which are quantitative, seek out scale, something that everyday photography provides readily with its volume and deeply conventional and ritualistic procedures, formal constraints and automation. The most photographed objects in the dataset are the most likely to be recognised. But Petraitis also has an interest in the trace and the photographic accident, the planar flattening of bodies and objects, and the poetic observation. These qualities immediately construct a complex relationship between image and interpretation that problematises machine learning.

Ulises Ali Mejias, in an essay entitled The Network As Method For Organising The World in his book Off The Network, observes how in systems of networks, components of that network, called nodes, can only recognise other nodes: Mejias calls this nodocentrism, because it defines the relationship of programming, which is constrained by parameters of pre-identified or structured familiarity. Nodes will fail to identify another object, even if it is in vastly closer proximity than any other node on the network: it simply cannot see it, and excludes it from its perception. And so it is with the image: that which is not within the image bank does not exist, which is to say, that which is not already photographed cannot be identified. Only photographs which are sufficiently conventional, with formally recognisable subjects and strategies of depiction, exist within the visible world of machinic understanding.

Paulius Petraitis, “a close up of a cage, confidence: 0.892115951 / a close up of a cage, confidence: 0.8977172”. From ‘A man with dark hair and a sunset in the background’, courtesy of the artist

Petraitis is testing machine learning technologies, though his target might be equally described as our confidence and faith in technology, and the methods of its deployment. As ideological as the stock market’s measure of confidence, computational developments within networked media and data processing participate in a targeted future that is eulogized without disclosing political value systems or its likely structural consequences: it remains a black box of sorts, a future promised and simultaneously hidden: we know, from writers as varied as Rebecca Solnit and David Graeber, that promises of technology have thus far driven forms of atomization from the promise of a convenient and automated future that is forever deferred. In its place of vision, we now have confidence. But Petraitis’ project takes machine learning at its word, at least to begin: he examines its learning capacities, both by measuring its progress over time, but also by permitting a direct relation to be drawn between the image and its reading – a semiotic act, in which we as viewers can participate, comparing the caption to our own understanding. And yet we might sense that Petraitis also asks a more complex and serious question than this: if we are going to entrust a lot of our decisions to devices and software, then shouldn’t we know what and how they think? What kinds of meanings do they produce, enable, or reinforce? if a machine claims the capacity to interpret based upon confidence – is it’s confidence warranted or misplaced?

Auto-generated captions quickly become telling: a long mound of snow beside train lines becomes a train covered in snow; a picture of plants and plant shadows, and a line where wall and floor meets, becomes a vase of flowers on a table: additive, and presumptive, the images described by the captions are compounds of objects, attached occasionally to assumed styles of photographing. The confidence of the program is nevertheless rising: a number of images are described as close-ups, claiming not to be tricked by strong line or all-over texture. Many of the captions are of course comic: a cat strolling across a stone wall becomes a black bear walking across a bridge: as if discovering the world for the first time, the software mis-recognises like a child, mis-naming whilst producing plausible or understandable analogies of what is depicted. There are echoes here of Henri Bergson’s conception of comedy as emerging from both exaggeration and the humanising of the machine.

Paulius Petraitis, ‘A man with dark hair and a sunset in the background’, courtesy of the artist

A close reading, looking across the wide range of images that Petraitis exposes to the programme, reveals that depiction is its horizon, and denotation it’s limit. Perhaps it will eventually produce the illusion of more, but to what end? Petraitis regularly shows us camouflage hiding in plain sight. A green butterfly is a leaf – plausibly so – but white tarpaulin is, in two versions, either a building or a bridge covered in snow; the complexities of representation are inevitable, but are also tellingly distant. Moreover, and of greater significance, the normativity and prescription of the image become evident: among the most confident of images is a view of two shop mannequins, in which a masculine figure is suited whilst a feminine figure, to the side, is wearing a jacket atop a patterned black dress. It is ‘a man wearing a suit and tie and standing next to a woman’ (confidence 0.979141057 on a scale of 0 to 1), and, in its refined later form ‘a man and woman posing for a photo’ (0.9011536). Perhaps it is a relief that as knowledge becomes more complex, confidence diminishes – after all, the more we know, the more we are conscious of what we do not understand – but we might note that its confidence remains seemingly stratospheric, its comprehension far from any difference between the real and the representation.

The role of machine learning is a critical field of technological development. But what does the computational study of images have to say about photography, and the universe of images that it courts and attempts to survey? So far, and perhaps always, we might note that everything is flattened to types. The denotative thrives, but complexity is elided: limit is hidden under a veneer of certainty. Petraitis has attempted to ask this process some questions, testing but also feeding the dataset with new and complex images to read. If machine learning is to grasp the photograph at all, it will need to reckon with the logics of a photography that is not simply the production of conventional pictures, but the ongoing search for new images, and new types. Those experiments in photography whose images hold no pre-existing key or unit of measure will be the true test of a machinic intelligence.

Imprint

| Artist | Paulius Petraitis |

| Title | A man with dark hair and a sunset in the background |

| Publisher | Six Chairs Books and Lugemik |

| Published | 2020 |

| Index | Duncan Wooldridge Lugemik Paulius Petraitis Six Chairs Books |