27 August, 2020, 12:24 p.m., Kettenbrückengasse, Vienna

Daniel Spoerri: You are in your thirties and you are an artist. When and why did you begin making art?

Sophie Thun: Apparently, I already wanted to be a painter as a child. When I went to school in Warsaw, there was a boy in the grade above me who planned to apply to the Academy of Fine Arts, and he took drawing lessons. Thanks to this, I realised that it was even possible to apply to an art university, and I also started attending preparatory classes. I was accepted at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków on my second attempt. I studied graphics there, but left for Vienna after three years, because I wanted to study painting with Daniel Richter.

How did you know what Richter was doing, and that you wanted to study with him?

During the summer holidays, I used to work as an au pair in France. One time, when I was in Paris, I went to the Pompidou Centre, right when they were presenting their Big Bang exhibition. There I saw a canvas painted in a way I had never seen before. It made a great impression on me.

Was it a Richter painting?

Yes. It was titled Duueh, and it showed people falling. I made a note of the artist’s name, and dreamed about studying with him in Berlin one day. At some point, I was in a relationship with somebody who was studying psychology in Vienna. It turned out that, at more or less the same time, Daniel Richter had moved from Berlin to the Austrian capital.

Lucky you.

Originally, my plan had been to go to Vienna for just six months, and now I’ve been here for twelve years already. I think I have lived here even longer than you. How many years have you been in Vienna actually?

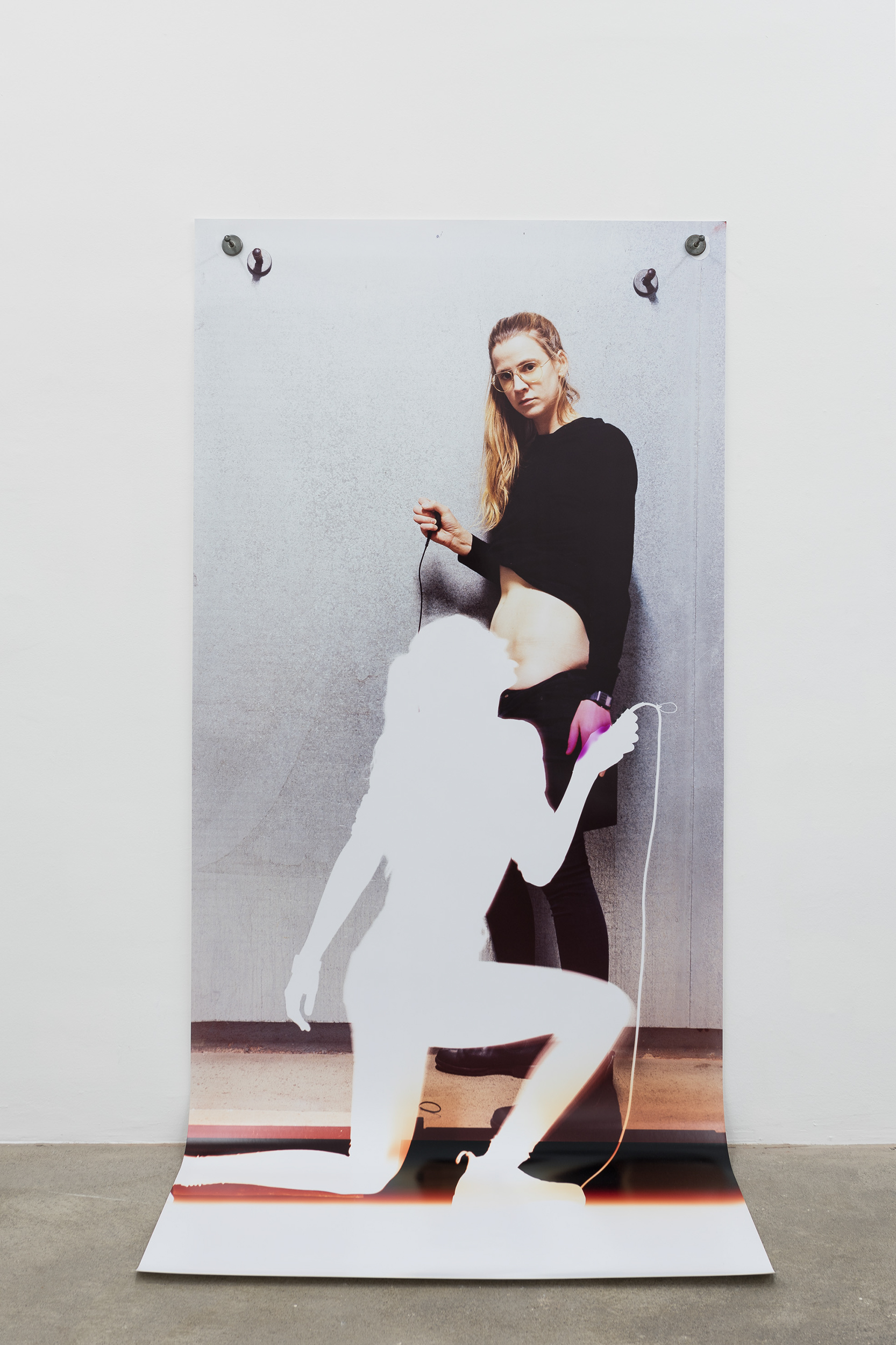

Sophie Thun, ‘Double Release (Autocunnilingus): The Letting Go’, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Sophie Tappeiner. Photo by Maximilian Anelli-Monti

I don’t know. I arrived in 2007, which is thirteen years ago. But let us return to you. You still have not answered the question, ‘When did you decide to become an artist and why?’

I guess I have always been interested in art. As a child, I used to go to exhibitions with my dad a lot. But I didn’t think that I could be an artist myself. It was like that until the age of sixteen.

At that time, was it only painting that you regarded as art?

I applied [to art school] for graphics. There were three departments in Kraków at the time: painting, graphics, and sculpture. Graphics covered a fairly broad range. At least that’s what I thought, and I also figured I could learn a profession there, like book design or something.

Did you have a conception of what art is?

No, I didn’t have any conception of this sort. What interested me most about art at the time was experimenting. I was interested in working with the given conditions, an interest I maintain today. Did you have a clear conception of art when you began doing it?

No, but I had problems, and I had to solve them somehow. At first, I was a dancer. I did not have the talent to become a classical painter, who draws, and so on. I still can’t do that.

In my case, I had difficulty speaking. I was afraid to speak in front of people. Apparently, I still speak too softly, although now, talking to you, I am trying to speak loud and clear. At the time, I felt like the visual was closer to me as a form of expression.

In Vienna, were you in Daniel Richter’s class right away?

Right after leaving Kraków, yes. But in Daniel’s class, I barely had the courage to do anything. The large number of people in the studio proved to be challenging for me. I prefer to work alone.

It is so important for you to be alone when you work?

Yes.

Of course, because when you create, you seek to communicate something. We are also communicating now, but not through painting. When you are alone, you need to find another means of expression.

I think I was also drawn to art because I like to be doing something by myself for hours on end. I enjoy spending my time this way. That is also why my practice is analogue: I like to spend hours and hours in the darkroom, working very slowly. Not checking my phone, etc. When I was studying with Daniel, I found out that there was a darkroom downstairs. It turned out there was a space at the university where I could close the door behind myself and be alone. That was very comforting, and it’s part of the reason why I switched from painting to photography in Vienna.

Sophie Thun, ‘Stolberggasse’, exhibition view, Secession, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Secession. Photo by Pascal Petignat

Ah! So you shut yourself up in the dark?

Yes.

You shut yourself up down in the dark. Not the opposite. When I imagine a photographer at work, I see pictures being made in the light. You, however, begin at the back door—in the dark.

Yes, that initially drew me to photography. The darkroom itself, not the photographing part.

Did you have a camera from very early on?

No, I didn’t have a camera when I was little. My mom said film was too expensive for children to use. They bought me a camera later on.

Of course, back then, it was still roll film being used.

Yes. My mom had a camera and she took wonderful pictures. She also put together old-school photo albums.

Today, photography’s not so expensive anymore, being digital.

Yes, but I still work with film.

Why exactly with film? Because it is something material, tactile?

In the past, I used to paint, and I was accustomed to a process during which you create something specific.

So to create an object.

Yes, just like you do: when you glue, it is happening while you are making it. With photography, it struck me as strange that photographing can be just pressing the shutter release, and someone else can do the rest for you in a lab; that the materialising happens somewhere else. Given that one even decides to have the image in ‘physical form.’ For me, it is the process that is most interesting. The process by which the image materialises. That’s why I work analogue, cutting negatives, making collages, etc. I am interested in the combination of the two processes: the photographing and the darkroom part. I wanted to make both visible.

Where do you perceive the difference is between men who make art and women who make art?

At the beginning of this conversation, you asked me about what my conception of art was. Perhaps this is one of the differences? When you grow up with an interest in art, you look at art books, you go to exhibitions, and almost everywhere, you see men, male artists. At least, that’s how it was when I was growing up.

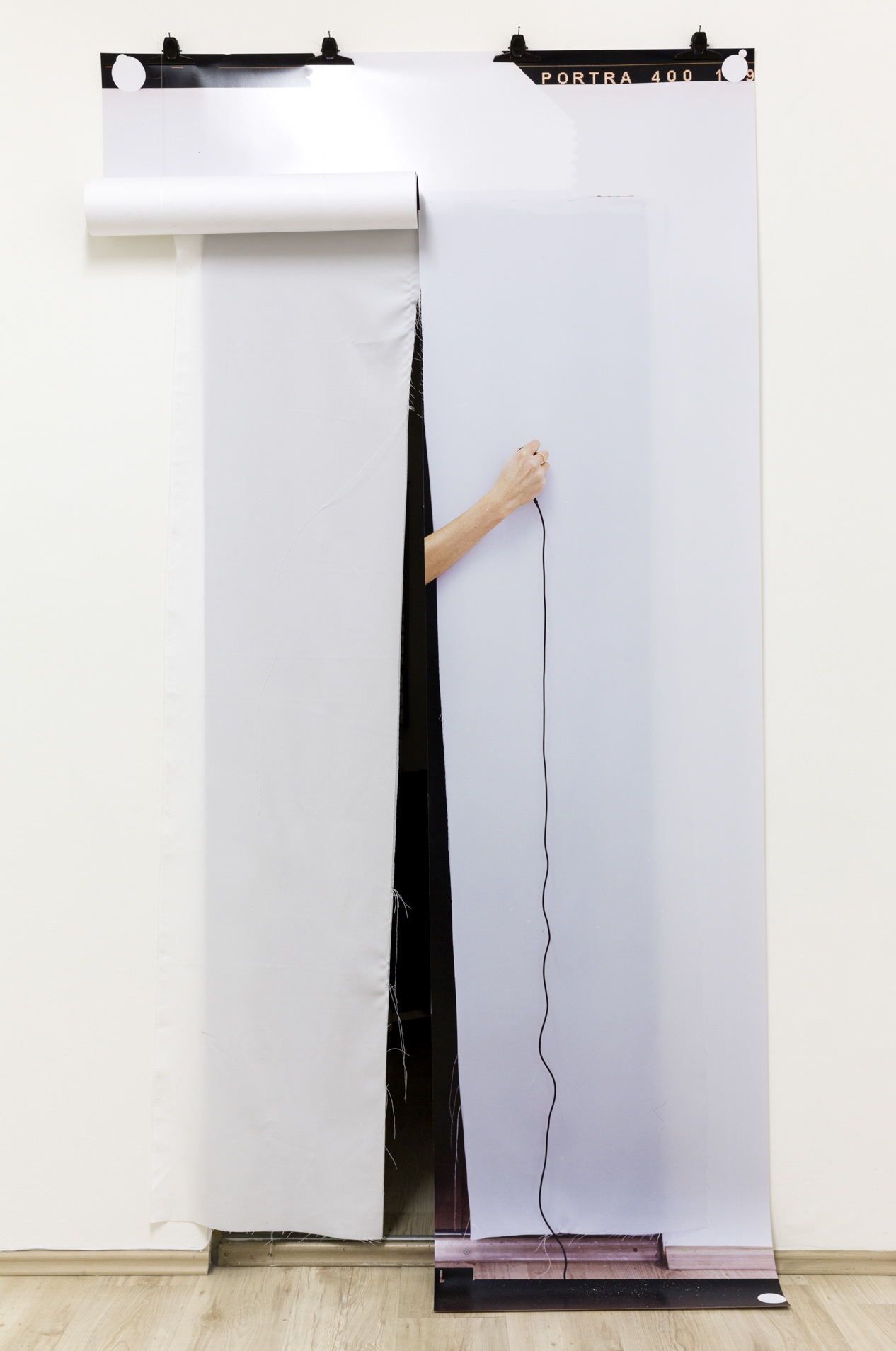

Sophie Thun, ‘Double Release (Durchgang / Passage / Przejście)’, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Mz* Baltazar’s Laboratory. Photo by the artist

When I was still a professor, at various art academies, there were generally slightly more women studying, but it was usually the men who continued on as artists.

Yes, and this is probably due to the whole system, among other factors.

The sexual act itself demonstrates that the man takes possession to a much greater extent, and the woman receives—

Or she gets raped.

How’s that?

In art history, there are so many depictions of it happening against the woman’s will: the rape of Europa and all those stories in which Zeus shapeshifts and abuses.

Maybe this would be the reason to make art, as a woman, being the one who receives, because the man just empowers himself and takes possession.

Photography as a medium also takes possession quite strongly. You shoot a photograph, you take a picture. It is somehow also about taking possession.

Yes, exactly.

It is somehow a very aggressive medium that is strongly connected to taking possession. That is why I always ‘use’ myself when I want to depict the body: so as not to expose others to potential violence. Also, I am always available to myself, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. In the beginning, I only depicted the spaces in which my exhibitions took place. Only later did I begin incorporating myself.

Was an interior simultaneously the reason for working on an exhibition and the exhibition’s theme?

Yes.

You also situate yourself in that interior. Is there a difference? You say that you are your own medium and an extension of your technique. From what I know about your work, I was under the impression that you photographed only yourself. I had no idea about the spaces. It’s you in a specific space, or are these two different things?

At a certain point, I combined one with the other. At the very beginning, it was only the representation of the space that interested me because photography tends to conceal reality.

You said that you photograph the space in which you exhibit.

Yes. For example, I would photograph a section of a wall, make a 1:1 print, and then hang it in the exact same spot on the wall. I was using photography to both show and literally cover reality.

Stealing reality?

In a way, I guess, yes. I make it visible by depicting it, but simultaneously invisible, through the image that covers it.

So you are appropriating reality?

Yes. My point is that photography as a medium often does this anyway: it appropriates and shows a specific image of the world. I am also interested in the connection between art and architecture. I think this comes from my Catholic upbringing, because in churches, especially baroque churches, the art is often interlaced with the architecture and it is not easy to separate the two.

Sophie Thun, ‘Reorganised (Agatha)’, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Sophie Tappeiner. Photo by Kunst-Dokumentation.com

The whole interior is shaped toward a certain purpose.

Yes. What fascinated me as a child was how blurred it is—whether a space belongs to an image or whether the image is part of the architecture. Building an illusion in the style of a trompe l’oeil. I am also interested in showing both the place where a photographic image is produced, i.e. the place where I take a picture, and the darkroom, i.e. the place where I later make a print. I almost always make use of the photogram technique, and, indeed, my work is usually a combination of a photograph and a photogram, where I am seen as the photographer and the exposer. After all, a photogram is created in the process of exposure. In other words, you have the time-lapse all in one image. Everything in the picture is happening at once. In photography, there are usually more processes: the shutter release moment and then the exposure or printing. I try to make these processes visible and to compress them into one image.

You used to be a professional photographer. Do you still do commissioned work?

I have always accepted assignments, but I have never been a professional photographer. I have worked in production for other artists—as a technician, standing behind the camera or processing film—so that with the money I earn I can make my own art, buy equipment, etc. I still work as a camera operator every now and then, sometimes I teach, and so I’m still doing a lot of things at once.

Don’t you think that men are, by nature, more aggressive than women? The man, he penetrates, which makes him the more aggressive one, and he maintains that role. At least for me, that is the difference. You don’t see it that way at all?

No, not really.

Out with it then: Do you think these are just old-fashioned notions about the sexes? Is there no difference at all for you?

A man can also be penetrated and be the receiver, and a woman can also penetrate. I am perhaps more interested in what people perform. There are women who perform masculinity and men who perform in a more feminine way. I perceive these roles socially more than biologically.

Sophie Thun, ‘Ufer, 17–27.02.2019, CW’, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Sophie Tappeiner. Photo by Kunst-Dokumentation.com

Well, yes…

One is more comfortable with this and the other with that, and, well, they are defined as masculine and feminine. But there are also people who move between these categories and do not define themselves as either one or the other. Do you think so-called biological sex influences art?

But one is art. What one has to say has to do with what one is, does it not?

Yes, in some cases it does. But not always. Sometimes it is—

You think there is no difference if it’s a man or a woman making art?

I think there is a difference, because the woman often works under different circumstances. In history, this difference is sometimes evident. You can see it in the formats of the works. Women often did not have either the time or the money to engage in art. Men practiced art as their main occupation, women had to do it on the side. Unless they came from wealthy families, but maybe not always then either.

What do you wish to convey as an artist?

Oof. I am interested in photography as a medium, and in what this medium does to people. It is a medium that also interests me because it is increasingly replacing language these days. Many people prefer to send a picture instead of describing something in words. I mainly take photos with the phone so that I don’t have to write something down—the name of a street, for example. Or, in a classic way, I treat a photograph as evidence. In fact, I am not really interested in photographing, although I use large-format cameras. I actually take very few photographs. When I am working on a collage, I shoot two photos because I need two negatives, but I take only those two photographs. I recently took four photographs and I was shocked—so many in one day! Additionally, large-format film is so expensive. Photography is a medium with very high production costs, and it sells for far less than painting. You have a lot of expenses but you earn less. Every so often, other people, like you, help me out. Do you remember when you offered that I could have a darkroom in your studio for free for a year, or was it two? In art, I often refer to my working conditions. I used this context, for example, when working at the Vienna Secession, where I produced two exhibitions during the time I had my own ongoing exhibition there. I simply moved my darkroom into the Secession.

You worked there as if it was your atelier.

Yes, I did.

You were fortunate that all the museums were closed in the spring.

Yes, it was a boon amidst disaster. It was great for me, because I could do whatever I wanted to in this wonderful place.

And no one disturbed you.

And I didn’t have to adhere to any rules. I had the keys and could come and go as I pleased.

You had an enormous studio.

Gigantic like never before and gorgeous. And I’m always doing something on the side anyway. During the exhibition, I produced the next two exhibitions. Three, in fact, as it turned out later. It was like when I was hired as a technician by these other artists, and I came up with these collages where I have sex with myself. I had my own exhibition to prepare and at the same time I was working on four commissions in various places for other artists. During the day we worked on their art, and at night, after working hours, I produced my own works back at the hotel. I used the rooms that someone else had paid for, and I turned them into my studio. That’s the reason this series of photographs is called After Hours. These works are also in some way about hierarchy and interdependence, because these artists depend on me in a technical capacity, and I am dependent on them financially. Without them, I could not create my art, and vice versa. Plus, I think they’re funny, these works.

Sophie Thun, ‘Stolberggasse’, webcam view, screenshot, Secession, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Secession

It is apparent to me that the very process of creating photography is what is of greatest interest to you. I am much more emotional. I create under pressure.

Yes, I also make art under pressure. I always have a total crisis at the beginning. I don’t do a thing, and then I really have absolutely no clue what to do. Then I think everything sucks. I keep postponing deadlines and end up working nights to barely make it in time. I haven’t found a way to handle all this yet.

I think this is good.

You think so?

Yes, absolutely.

It started with the fact that I always had to find time for my own art between jobs, and so there was always this pressure. At night, after work, on trips, in hotel rooms. You end up having hardly any time to sleep. I have the impression that it helps me—that I put things off for so long because then the fear of starting is gone. There is no time left for fear.

You just have to start doing.

Yes, there is no more time left for the fear barrier.

It’s funny. No time for fear.

I think that getting underway is still the hardest part. At least for me, it’s a major hurdle. I have always been envious of people who go to the studio every day and paint.

Yes, I know what you mean. I also knew such people.

And there they are, painting away, while I’m lying in bed paralysed by fear.

They create art exactly as if they were going to the office. At ten in the morning, they open their studio. At one, they go out to lunch. And so on.

Unfortunately, I don’t function like that.

Neither do I.

But it’s exhausting.

You get used to it over time. But the doubt remains, as to whether you should do anything at all.

And whether you will succeed at doing something again.

Yes.

Before an exhibition, I often feel as if everything I am doing is kindergarten. But so far, I have always been satisfied in the end.

Sophie Thun, ‘Extended Double Release’, exhibition view, Galerie 52, Essen, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie 52. Photo by Nils Limberg

And the jobs?

A luxury. Thanks to them, I do not have to make any compromises in my practice. If I absolutely want to show something in a gallery and the gallery tells me that it will not finance it because it cannot be sold, then I can finance it myself. Also because I can do it almost all by myself. During the lockdown, I realised the extent to which having technical and production skills assures me of independence. I have a space and my body at my disposal. I am my own technician, I can process my film myself, and so on. During the lockdown, even the labs and darkrooms were closed. But I could work. It is important for me that, when it comes to my creativity, I don’t need to compromise.

That is important.

Organising your own freedom. I just need to learn to say more often that something isn’t for me, but I’m getting better at that, too. I do give interviews. I suffer through them, but I think I have to, because if I don’t talk about my work myself, then someone else will do it for me.

During an interview, it becomes clear to oneself what one does, because it needs to be explained and put into words.

Daniel, you do much more photographic work than I do. You took so many snapshots. Your famous Tableaux pièges are basically snapshots.

They are. At first, when people did not know what I was doing yet, they said I had merely taken a picture of the table when I showed them pictures of my work. They did not understand that this table was hanging on the wall and was the work.

I can imagine, that the situation being a work of art was incomprehensible. It is a bit like taking a picture. In my work, I am not interested in the snapshot, in this whole ‘decisive moment.’ I am much more interested in stretching and rolling up time. Although when I take a picture, I of course freeze time.

I do not understand your point.

My point is that, in my works, different moments in time overlap.

Do you mean different ‘phases’ that you later combine into one photograph?

Yes. And with you it is one moment, like in the Tableaux pièges. In fact, this is a classic photographic question. In photography, I am more interested in the process as a whole: everything that happens after taking a picture, or not taking pictures at all, only using photographic procedures.

This is an interesting point. You make collages to a much greater extent than I do, and yet your works are called photographs whereas mine are called collages.

It’s true that these large-format works are also collages.

Exactly, they are collages comprised of many stages of time that you fuse together.

Also in several parts.

For me, there is this one moment that I catch and record.

It’s funny. If you were to do this kind of work with the table right now, I would lose my computer and phone. If you only said, ‘Now!’

We could end this interview now. When you say, ‘Now!’ Now is not later, it is now.

I am not particularly interested in linear time.

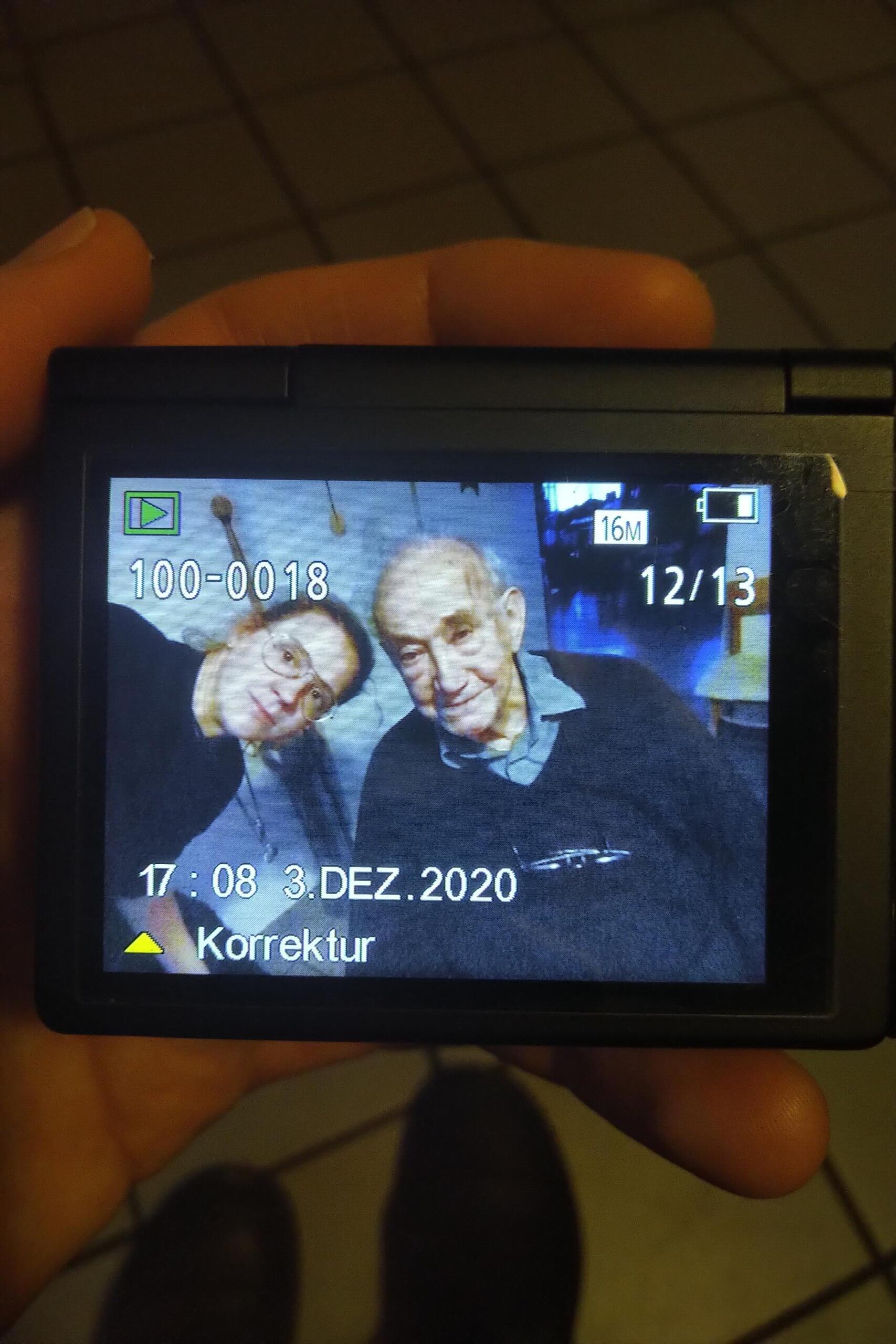

Sophie Thun and Daniel Spoerri, 2020. Photo by Sophie Thun

Me neither.

You also have this idea that the air in the apartment is thick with the people who were here before. That everything remains and accumulates.

Yes! If it could be filmed, it would be a densely packed room. Where you are sitting, hundreds of others have sat before you, and they are all stacked up, one on top of the next.

Indeed! I think it was Roland Barthes who spoke of the ‘that-has-been’ of photography. And in these collages where I make love to myself, different points in time coexist, they are assembled together. However, it didn’t happen this way, the interaction is artificial.

A collage of different time intervals, different moments.

Yes. Photography interacting with photography. Not myself with myself, but rather photography in intercourse with itself. As in this work, where the photograph is being satisfied by the photogram. Okay—now!

Now!

The text is an effect of work on the exhibition I Do Not Share with Anyone which was to be shown during Cracow Photomonth 2020. Information on manifests, presentations, conversations and artworks made by the participants of the exhibition and a PDF catalogue will be available on the website photomonth.com/pl/portfolio/z-nikim-sie-nie-dziele.