From the perspective of the history of architecture, Lviv still remains the capital of Galicia. For many years this period of the city’s past has been the most frequently investigated and analyzed. The borough by the Poltva River was located on the eastern peripheries of Austria-Hungary, and its peculiarity is caused by historicism, Eclecticism of Viennese roots, Secession and – foreshadowing Modernism – experimental large-city works created just before the outbreak of the First World War. However, another stage of Lviv’s development – from the period of the Second Polish Republic – remains hardly known and not appreciated, even though a considerable modernization of the city’s architecture and urban planning took place then. Directions of territorial development specified at that time were carried on throughout the following decades, also after the change of borders in 1945. This vast transformation was not interrupted even by the loss of metropolitan status from the times of the Habsburg Monarchy. During less than two interwar decades – as a result of the expansion and broadening of borders – the number of inhabitants of Lviv increased by one-third. Due to this fact, the city, which in 1939 had around 330 thousand inhabitants, was the third largest city of the Second Republic of Poland.[1]

Therefore, while analyzing the Modernist architecture of Lviv, we locate the city on a completely different map, which may be sketched with reference to both political borders delineated after the First World War and to civilizational processes which started then. It is worth mentioning that such maps were co-created by Eugeniusz Romer, a cartographer and geographer from Lviv, whose maps were used in Versailles during negotiations concerning the new shape of Europe and the borders of reborn Poland in the west. He also took part in organizing plebiscites in Silesia, Warmia and Masuria and in work on the Treaty of Riga in 1921. Proposals made by Eugeniusz Romer had a big influence on the final determination of the eastern border of the Second Polish Republic and they confirmed the inclusion of Lviv.

Eugeniusz Romer – comprehensively educated and having gained experience in Europe, North America and Asia – did not perceive geography only as a natural science. He also appreciated its social aspects. His investigations concerning the lands belonging to the Polish Republic before the partitions were to emphasize their organic unity and were intended to prove that Poland exists despite the current situation or political decisions and that the territory occupied by Poland is a geographic whole. At the same time, he added that his reference point was not only the part of land inhabited by Poles but also the lands of all nations from the former territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Appreciating their distinctiveness, Eugeniusz Romer considered that geography united these lands so strongly that “the means for their harmonious coexistence have to be found.”[2] The claims made by the Lviv cartographer, which emphasized that Lviv belonged to Poland, contrasted with theses of another geographer living at the same time and also connected with Lviv, namely a Ukrainian Stepan Rudnytsky, who shared the views about the social function of geography. In his publications, he emphasized the existence of the historically vast territory of Ukraine, which he equated with the areas inhabited by ethnic Ukrainians, from the river Poprad to the Black Sea and southern Russia. His ideas, similarly to those by Eugeniusz Romer, were to constitute the basis for endeavours to create an independent Ukraine, but obviously conflicted with a resurgent Poland, an observation which was described by Stepan Rudnytsky.[3]

Therefore, in Lviv just after the First World War, the issues concerning new maps and new borders were very complex, and they led directly to Polish-Ukrainian armed conflict. The war for Lviv and the monument of its winners – the Cemetery of Lviv Eaglets – shaped anew the identity of the city, which on 22 November 1920 was awarded by Józef Piłsudski the Knight’s Cross of the War Order of Virtuti Militari. In the Second Polish Republic, Lviv became a symbol of the fight for the borders of an independent state and a symbol of faithfulness to Poland. The motto Semper fidelis was placed in the city’s emblem and in 1925 the ashes of one of the nameless Eaglets were interred in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Warsaw.

In order to appreciate interwar Lviv, one ought to place it not only within the borders of the Second Polish Republic, but also on a map of the new East-Central Europe, which was gaining shape after the First World War and embraced independent countries created then – from Estonia to Yugoslavia.

Lviv, located now in the territory of resurgent Poland, could very quickly use the new situation, even though all its inhabitants – Poles, Jews and Ukrainians – remembered the recent civil war. However, the city did not become a place of radical nationalistic and ethnical conflict. In order to appreciate interwar Lviv, one ought to place it not only within the borders of the Second Polish Republic, but also on a map of the new East-Central Europe, which was gaining shape after the First World War and embraced independent countries created then – from Estonia to Yugoslavia. The year 1918 meant the creation of a new, until then unknown in this part of Europe, political reality and new opportunities for wide-ranging reforms resulting from it. The former provinces of European empires – frequently seen as the symbols of underdevelopment, for example Lviv in Austrian Galicia – very quickly became the place of the implementation of bold modernization projects and the new states consistently supported modernity. Placing Lviv on such a map of modernization allows for the appreciation of the city’s achievements which occurred in the period of Lviv’s belonging to the Second Polish Republic and, above all, it enables us to perceive modernistic Lviv as a fragment of a bigger process of East-Central Europe’s civilizational advancement taking place between the First and the Second World War.

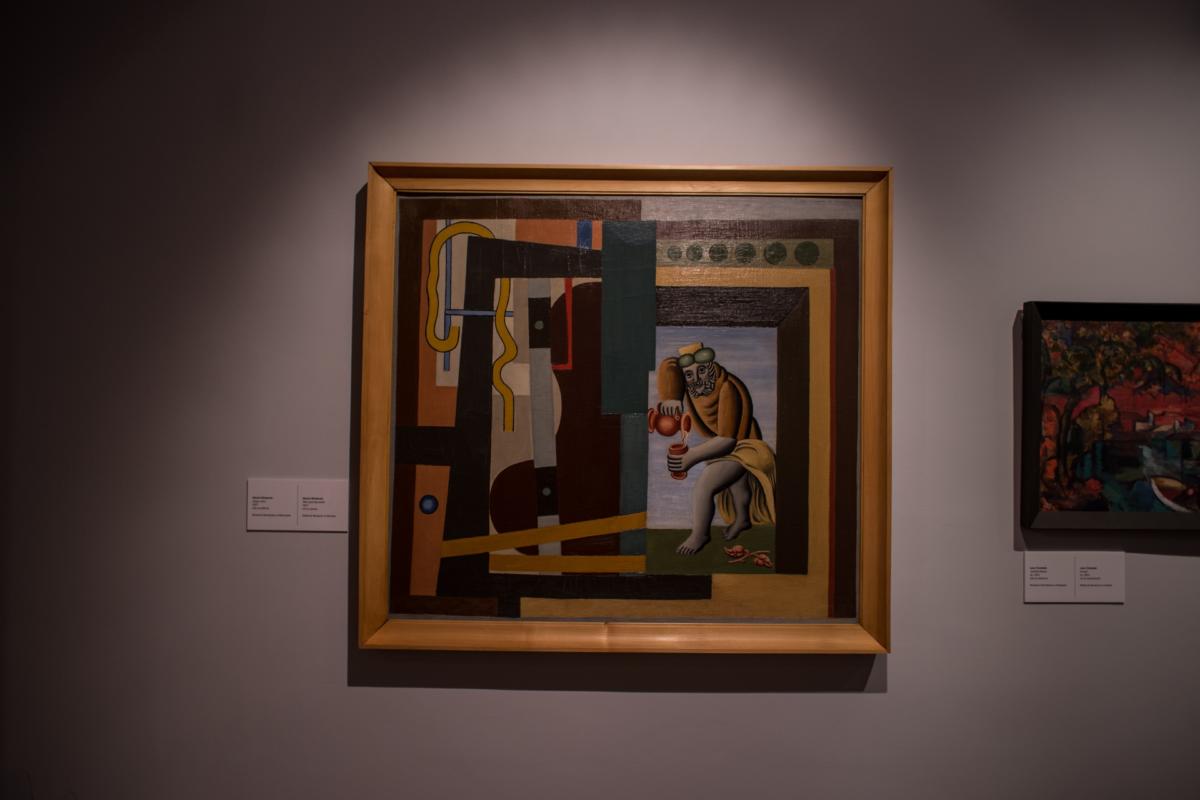

Above all, this is the Lviv architecture and urban planning that constitute evidence of the modernization process. While analyzing their history, it is possible to discover many processes that can be compared not only with what took place in Polish architecture, but also – more broadly – with what occurred in the whole Central European region. In the 1920s, references to representative Classicism and tendencies close to Art Deco appear simultaneously. However, already at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s, Modernist forms started to dominate more clearly. The way in which the city was perceived changed too, because what took place was not only its territorial development, but also changes in the fields particularly appreciated by Modernists – communication, hygiene, housing, education and social infrastructure. The history of the Modernist development of Lviv resembles the analogous processes which took place in all new East-Central European countries. The phenomenon of this regional Modernism may be described by juxtaposing many simultaneously occurring and mutually influential changes in political, social and cultural life, which were to transform this peripheral, from the perspective of the history of Modernity, region to become part of the “centre” of civilization. Thus, it is crucial to include the history of particular cities or provinces in the context of broader modernization processes, not to discuss them as if they were experiments separated e.g. from economic reforms or development of popular culture. Appreciating the range of modernization changes, one ought to contest a dominant point of view, according to which modernity was a marginal phenomenon in East-Central Europe, and traditionalist and nationalist statements objecting to modernization or at best ready to imitate in the 1930s modernization models from fascist Italy dominated in the region. Publications by Ivan T. Berend, who claims that East-Central Europe was an anchor of political authoritarianism, where art and architecture referring to conservative values were propagated, may be symptomatic here.[4]

At the same time, such a situation inspired radical artists, above all left-wing ones, to intensify activities, which were ahead of their time and constituted the manifestation of future, often utopian, changes. Therefore, valuable avant-garde art, which was however – treated as an enemy by the dominating political forces – doomed to remain marginalized and without a real influence on the surrounding reality, could be created in the region. Due to the weak institutional support and limited opportunities for development, the avant-garde from the “centres”, above all from Germany and the Soviet Union, had to be the reference point for this art. Meanwhile – looking at the complexity of interwar artistic life in the region and at the scale of civilizational changes, which were caused by the creation of independent countries between the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea and the Adriatic Sea – it is difficult not to agree with such a thesis. The intensity of modernization projects undertaken both by the governments of the countries and by the cooperative or individual initiatives was so significant that it is possible to perceive East-Central Europe as a region where bold, and what is the most important successful, modern reforms, not at all intended to serve the creation of totalitarianism, were carried out. It does not mean that anti-modernization and authoritarian tendencies, which constantly appeared throughout the whole twenty-year period and which created the political reality, were negated, but it draws attention to the fact that they were not able to stop the modernization process. The activity of local architects and town planners and the modernization projects realized by them ought to be examined in this context. One also ought to question the thesis about the independence of development of local architecture solely from external influences. The fact that creators working in the region were interested in the achievements of other Modernists in Europe and – above all – in the United States, was apparent, but it also did not result in the thoughtless imitation of their works.

A symbolic status in the history of Czechoslovakian architecture was ascribed to the city pavilion by Jaromír Krejcar. It was shown during a world exhibition in Paris in 1937, where it was the boldest example of modern architecture, clearly contrasting with totalitarian pavilions from Germany and the Soviet Union.

It is worth pointing out some examples of the creation of a modernistic “New Europe,” which denote a consistent search for original modernization projects. In the immediate vicinity of Lviv, a wide-ranging transformation of Carpathian Ruthenia, which was a part of Czechoslovakia then, was carried out. The authorities of the new country caused that the new communication infrastructure and development of cities, particularly the main administrative centre in Uzhhorod, where a new residential district and an airport were built, took place in this neglected region. e development of Modernist architecture in Czechoslovakia was the most dynamic among the countries in the region. Above all, in Prague and Brno there was a big and very well-developed community of architects, who realized such distinguished projects as the Baba district on the peripheries of Prague or the fair area in Brno. A symbolic status in the history of Czechoslovakian architecture was ascribed to the city pavilion by Jaromír Krejcar. It was shown during a world exhibition in Paris in 1937, where it was the boldest example of modern architecture, clearly contrasting with totalitarian pavilions from Germany and the Soviet Union. A Moravian shoe company named Bata was a specific example of Modernist experiments, insofar as within the original social policy from the mid-1920s onwards it built houses for workers designed by Modernists such as Vladimír Karfík and František Lydie Gahura. In this way, the workers were provided with modern living conditions. At the same time, corporate bonds within a capitalistic enterprise were created. By the end of the 1930s, the Bata company dealt not only with shoes but also with the production of full-length movies and planes. Willing workers were taught how to fly, which allowed them to fulfil a function as the company’s business agents travelling on their own using the company’s planes. The fact that the company’s management considered their own activity to be the best standard of modernity is supported by their lack of interest in the ideas of Le Corbusier, who in 1935 tried to start cooperation with Bata. After carrying out a few projects, including a new mill town of Hellocourt company in France, Le Corbusier parted with his would-be employer. Bata rejected the architect’s proposals as not compliant with its own philosophy of activity. The fact that Le Corbusier propagated filling new towns with blocks of flats rather than with detached houses was the main contradiction. The company decided that this discredited a fundamental principle of “live on your own, work in a group,” and as a result – the whole philosophy of social care over the worker and support of a propagated model of life typical for the middle class. The company’s founder Tomasz Bata associated blocks of flats with dehumanization and with the spread of communist ideas, which he strongly opposed. Polish Gdynia should also be mentioned among the modernization projects. There, within less than two decades a modern harbor used for transatlantic sailing and by the city with one hundred and twenty thousand inhabitants, filled to a great extent with Modernist tenement houses, was built. Gdynia is worth noticing also because it was instrumental in opening Poland to the world, literally and metaphorically, and consequently – it helped to conquer the trauma of partitions and lost national uprisings. Additionally, Gdynia was also a place where possibilities offered by a new geopolitical situation were used the most intensely. The aforementioned opening meant an expansion of seaside tourism and development of the whole coastline given to Poland. It was also related to a project concerning Poland’s obtainment of overseas colonies and the development of international trade, initiatives which were propagated by the Maritime and Colonial League since 1930. Modernist architecture appeared also on a large scale in the Baltic countries. Special attention ought to be devoted to the architecture of Tallinn and Pärnu in Estonia and to the capital of independent Lithuania in Kaunas. In the capital of Romania, already by 1929, Horia Creangă designed an icon of Modernism – an edi ce of the Romanian Insurance

Company ARO. In the 1930s, due to the development of the city centre with the creation of the monumental Brătianu and Ionescu boulevards, Bucharest became one of the European capitals of Modernist architecture.

After carrying out a few projects, including a new mill town of Hellocourt company in France, Le Corbusier parted with his would-be employer. Bata rejected the architect’s proposals as not compliant with its own philosophy of activity. The fact that Le Corbusier propagated filling new towns with blocks of flats rather than with detached houses was the main contradiction.

Paying attention pars pro toto to the history of architecture, one ought to perceive it in a broader context of other transformative processes in the region, from which to a great extent it resulted. It is worth mentioning just a few examples. “New Europe” generally had to build new infrastructure, especially for transportation, in order to connect the areas which had hitherto belonged to other countries, examples of which were particularly Polish, Czechoslovakian, Yugoslavian and Romanian efforts. The building of Gdynia was the first example of modernization projects inspired by Poland, among which the biggest meaning was gained by the Central Industrial District – a new network of cities and factories in central Poland whose construction started in 1938. In Czechoslovakia, money was invested not only in the development of Carpathian Ruthenia, but also in Slovakia. In Romania, in turn, the oil industry was developed and Transylvania, taken from Hungary, was con- nected with Bucharest. In Yugoslavia the territory between Belgrade and Ljubljana, inhabited by di erent ethnic and religious groups, needed to be integrated.

The activity of avant-garde representatives such as Karel Teige in Czechoslovakia indicates the fascination with possibilities of development created by “New Europe”. Moreover, this fact is confirmed by the words of Mircea Eliade, who claimed that only his generation who grew up after the First World War could fully develop its talents in the new political reality, without the constraints resulting from the necessity to achieve historical goals specified by others. The fascination with a new époque and a desire to find in it a clear place for oneself were inspiring also to the leading gure of the Yugoslavian avant- garde – the creator of the idea of the “Balkan barbarogenius,” Ljubomir Micić. Believing in the youthful power coming from the liberated Balkans and the Slavic empire which Yugoslavia was supposed to be, Ljubomir Micić emphasized that the achievements of Nikola Tesla, a genius inventor of Serbian origin, were the inspiration for the new art and faith in the modernization of Balkan power. While the comparison with Nikola Tesla was only a rhetorical measure, it is worth noticing that avant-garde creators in East-Central Europe took part in contemporary modernization projects whenever possible. A left-wing Prague architect, Jan Gillar, designed a town planning project of Mukacheve in Carpathian Ruthenia, and another Prague functionalist, Jaroslav Fragner, was the author of a design of a children’s hospital there (1922–1923). Also in the first half of the 1920s, in 1923, Władysław Strzemiński presented a Supremacist design of a railway station in Gdynia. It is also worth mentioning that leading artists of the Hungarian avant-garde, like Lajos Kassák, Sándor Bortnyik and Róbert Berény, who took part in the communist revolution in 1919 and had left Hungary for fear of repression, started an intensive activity in the commercial market after coming back to the country at the beginning of 1930s, considering the poster to be the best available medium of modernization of visual culture of contemporary Hungary.[5]

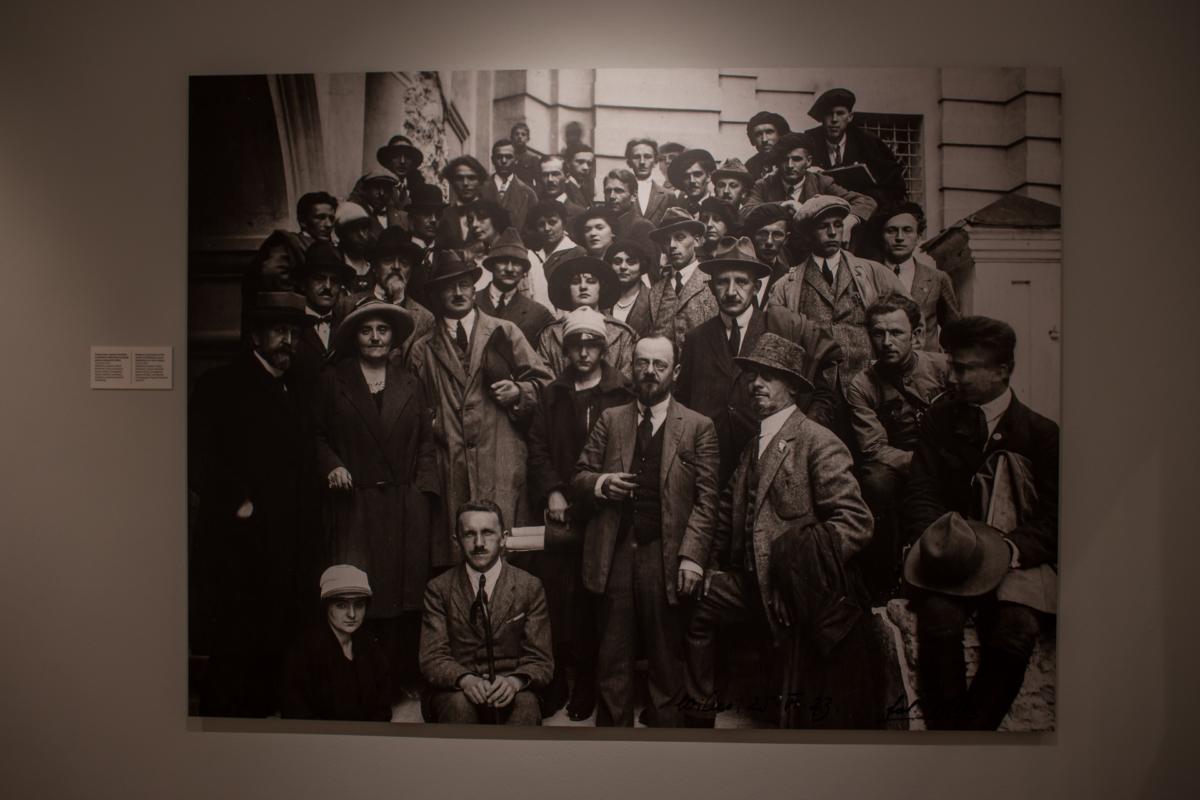

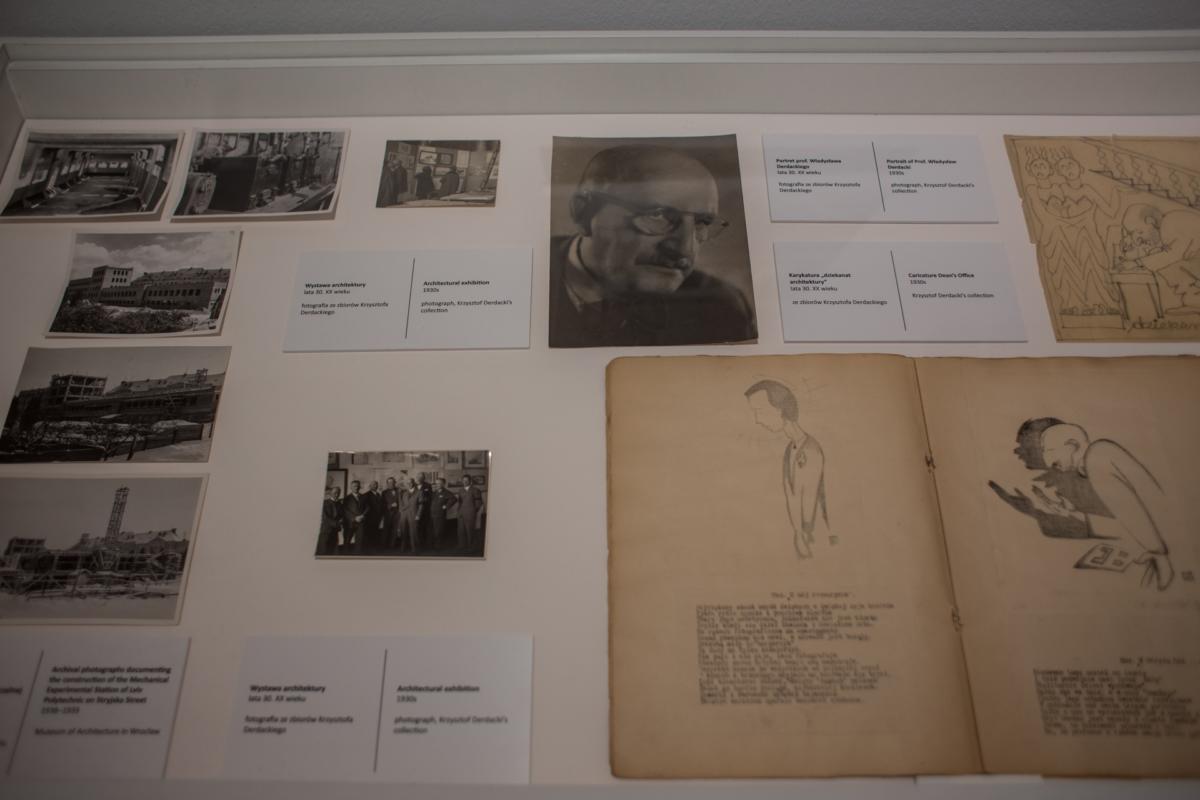

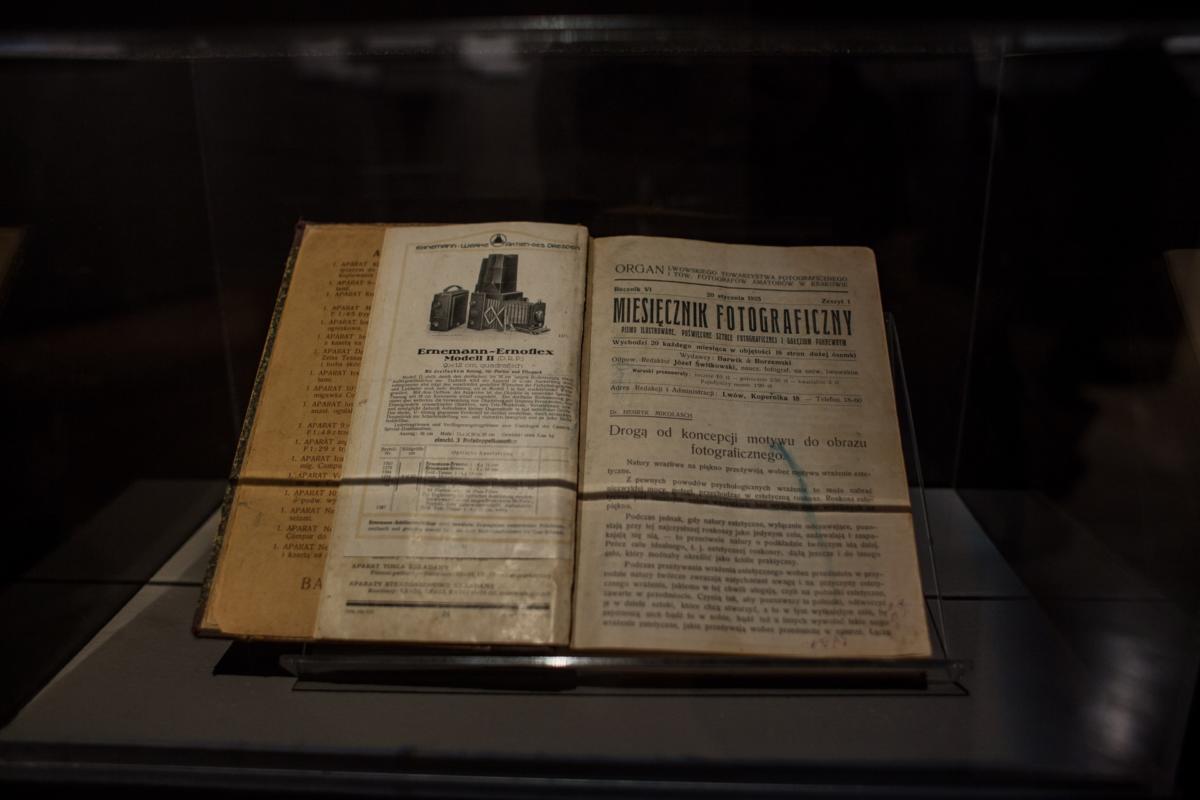

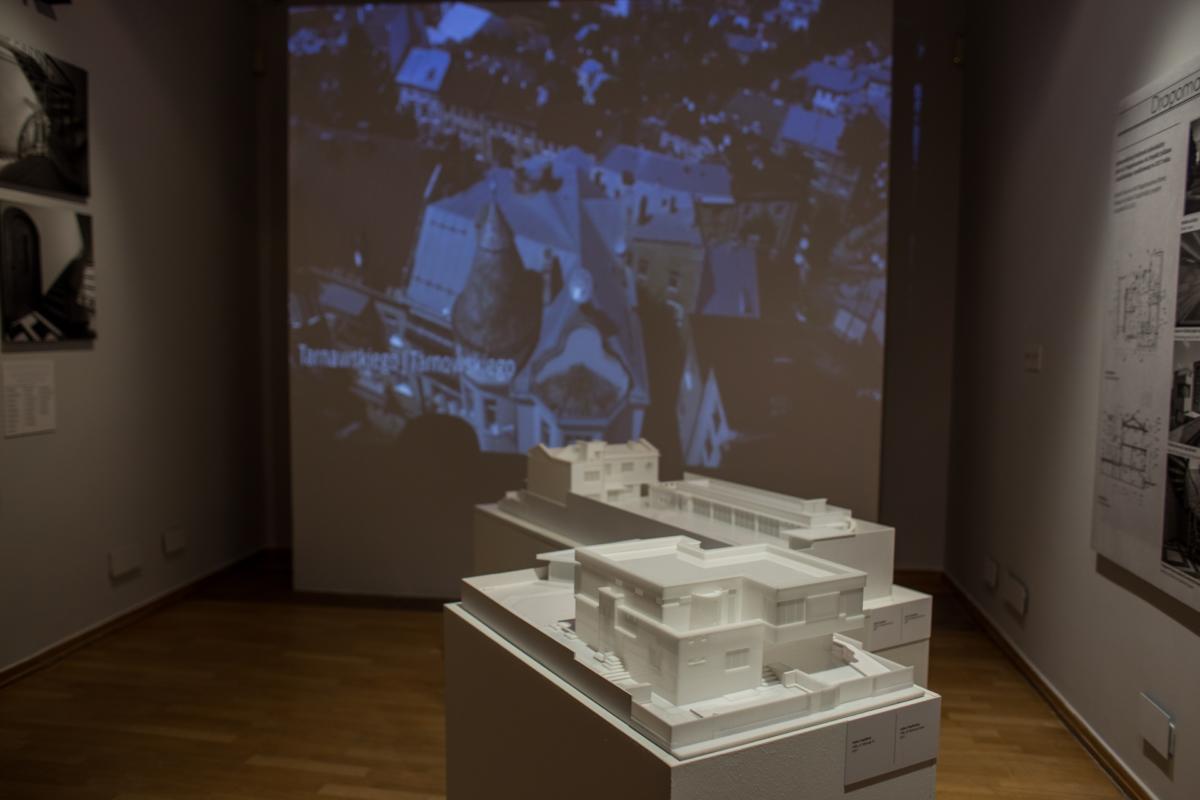

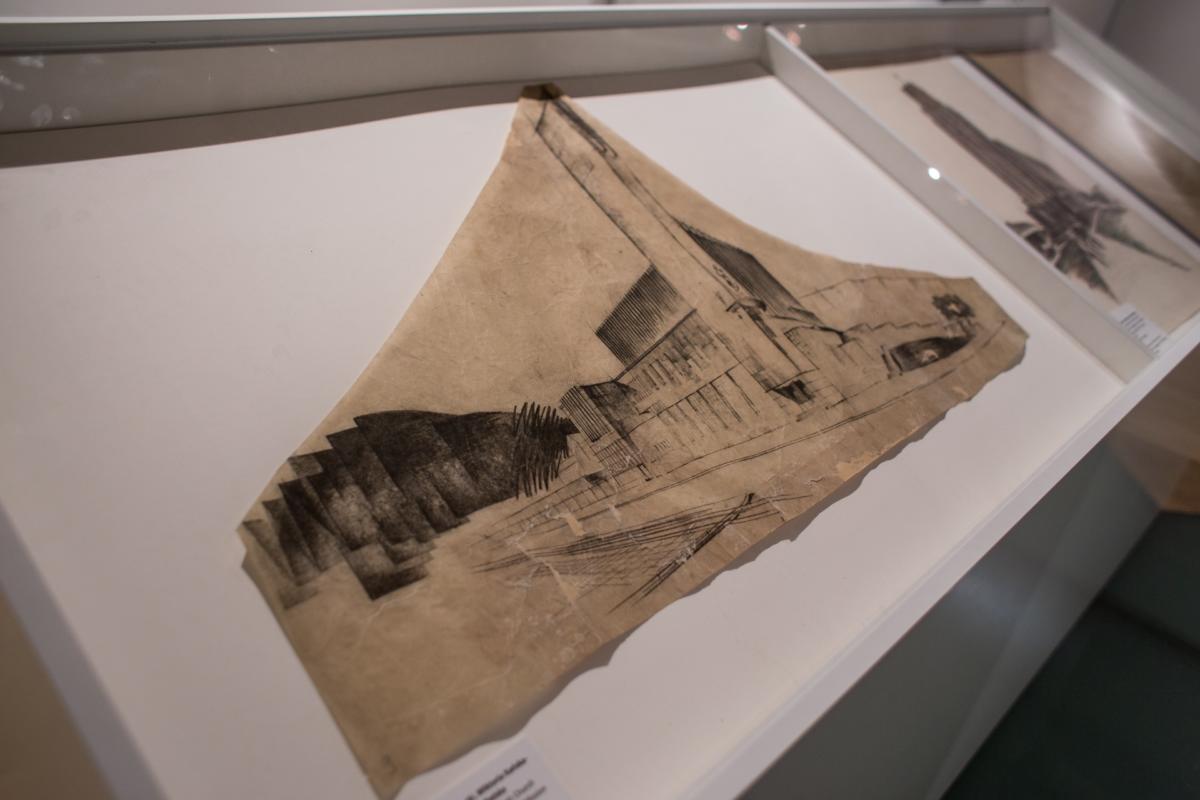

It is in this dimension of unusually dynamic and multi-layered changes that interwar Lviv should be perceived. In the Second Polish Republic the city belonged to the most important centres of modern architecture. Additionally, Lviv was outstanding as a seat of the distinguished Lviv Polytechnic and as an education centre for architects.[6] In Lviv, particularly because of Witold Minkiewicz, but also other lecturers such as Zbigniew Wardzała, Tadeusz Wróbel, Władysław Derdacki, Andrzej Frydecki and Tadeusz Teodorowicz-Todorowski – and even a supporter of historicizing and classicist forms Jan Bagieński – Modernism very quickly gained a dominant position in the didactic process. Working not only as didacts, but also as practitioners, these architects could give the city a new Modernist face. The existing urban fabric, both historical and the one from the Galician times, was significantly developed. It is worth pointing out some selected examples illustrating processes due to which Modernist architecture could fit historical buildings, becoming at the same time an identification sign of rising districts and a symbol of the new époque in the city’s history.

Similarly to other cities in the region, also in the exact centre of Lviv, at what was then Akademicka Street, in 1929 Jonasz Sprecher’s office building designed by Ferdynand Kassler was built. The building was a manifesting sign of modernity. Deprived of ornaments, its elevations contrasted with neighbouring late historicist architecture.

Similarly to other cities in the region, also in the exact centre of Lviv, at what was then Akademicka Street, in 1929 Jonasz Sprecher’s office building designed by Ferdynand Kassler was built. The building was a manifesting sign of modernity. Deprived of ornaments, its elevations contrasted with neighbouring late historicist architecture. The seven-storey edifice rose above other buildings in this part of the city center. Jonasz Sprecher’s office building opened a new chapter in the history of Lviv’s architecture, strongly emphasizing the modernizing dynamism of change. In many other cities of East-Central Europe similar activities were undertaken by architects, who intentionally contrasted old buildings with new ones, which is illustrated by the Feniks edifice built from 1929 to 1932, located next to the Krakow market square and designed by Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, or a seat of the Bank of Moravia by Bohuslav Fuchs and Arnošt Wiesner in the centre of Brno from 1928–1930. The appearance of residential districts, inspired both by the concept of “garden cities” and by functionalist housing estates and residential units, was another phenomenon characteristic of Central European Modernism.

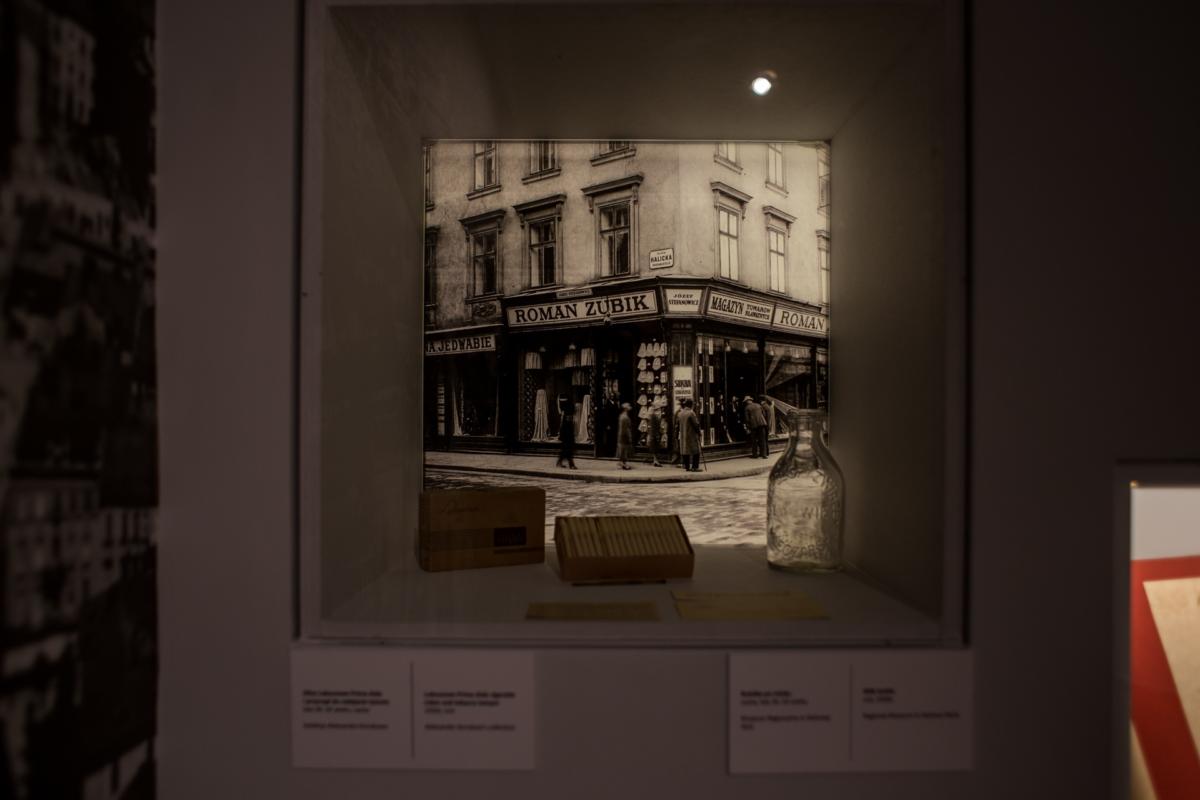

Such a need resulted from the quick development of many cities which until then had a marginal meaning but in the new political reality gained the status of big administrative or scientific centres. These changes were particularly visible in Poland, where following the period of partitions numerous urban centres until then deprived of any significant meaning had to be developed. This situation referred i.e. to Krakow, a provincial urban centre of Austria-Hungary, where a whole group of housing estates appeared to the west of the historical centre, Katowice – changed into the administrative centre of autonomous Silesian voivodeship, and also Warsaw, where model residential architecture solutions, above all in Żoliborz, started to appear. In Lviv, many analogous investments with varying degrees of comfort were built. They ranged from impressive housing estates at Na Bajkach Street (1926–1928) or a new housing estate called “New Lviv” from the beginning of the 1930s, through residential units designed by Witold Minkiewicz at Stryjska Street, to modest buildings of a housing estate created in the years 1925–1938 by the Worker’s Housing Estate Society. Similarly to other Polish cities, luxurious villas, particularly tenement houses built in the city centre, among others at Sykstuska and Wulecka Streets and designed by leading Lviv Modernists Witold Minkiewicz, Tadeusz Wróbel, Salomon Keil, Jakub Menker or Stefan Porębowicz, were the sign of the times. It is worth emphasizing that the times of the Second Polish Republic were for Lviv the period of development of educational, health and social infrastructure, which was related to striving for civilizational development on a larger scale. Examples of similar activity concerning the architecture with social features may be found among others in Estonia, where the building of a new network of schools with a Modernist form was a tool shaping educational policy of the country and strengthening the national identity of Estonians. Due to the increasing number of inhabitants, also in Lviv – above all in the second half of the 1930s – numerous schools and kindergartens were built, and the Lviv Polytechnic was developed. Analogously to other countries in the region, these projects frequently turned out to be a pretext for propagating Modernist architecture, which allowed for innovative educational purposes and provided students with hygienic and practical learning conditions. These activities were funded both by the city authorities and by social organizations, religious associations and private donors. The care for the quick development of sport buildings, due to which the interwar city was enriched among others with a big complex of swimming pools including “Żelazna Woda” from 1933–1938 (Adam Kozakiewicz, Leopold Karasiński), was a novelty. A sanatorium for tuberculosis patients at Kurkova Street, whose monumental five-storey edifice raised in the years 1927–1929 was built in simple functionalist shape (Adolf Kamieniobrodzki), ought to be perceived as a special achievement. Modernist Lviv also became an important economic centre, which was expressed in

the architecture by the development of a fair area, where from 1921–1939 the annual international Eastern Fair took place. They were considered to be one of the most important fair events in the Second Polish Republic. Their aim was to develop trade and other economic contacts among Polish and foreign entrepreneurs, including those from the countries of “New Europe,” which in the Lviv region bordered with Poland, i.e. with Czechoslovakia and Romania, but also Austria, Germany and Yugoslavia. In the whole history of the fair, there were 23 countries that took part in them. On the government’s initiative, the fairgrounds in Stryjski Park, previously used among others in the organization of the Polish General Exhibition in 1894, were significantly expanded to the area of 220 thousand square meters. The necessary communication infrastructure (telephone lines, gas, a tramway, a railway spur) was added and one hundred and thirty permanent exhibition pavilions funded by particular companies, public and city authorities were built. They were designed by the most important Lviv architects, including Jan Bagieński, Eugeniusz Czerwiński or Tadeusz Wróbel. The pavilions illustrated the evolutionary changes in the architecture of Lviv – from manor-house style, through Art Deco, to innovative Modernism. Manufacturers of machines, means of transport, textiles, metal works, and representatives of the food and chemical industries, i.e. the areas accounting for the development of a modern economy, were meeting in Lviv.

Endeavours aimed at developing cities into centres of international trade also resulted from changes in East-Central Europe and from the efforts to gain economic prosperity, which was the condition necessary for civilization’s development and, as a result, for retaining sovereignty by the new countries. In a situation similar to Lviv were also other cities in Poland, including Vilnius, where in the fashion of the Eastern Fairs, the Northern Fairs aiming at developing contacts with countries located around the Baltic Sea were organized in the years 1928–1939. The fairgrounds in Czechoslovakian Brno developed even on a larger scale and can be perceived as analogous for Lviv. In 1928, international fairs were organized there, also in pavilions built in Modernist forms, often with a radically modern character, created by leading functionalists from Brno, like Bohumír F.A. Čermák.

Modernist Lviv occupied a significant position on the map of not only Poland, but also of “New Europe” and should be classified as one of the most important centres of new architecture of the region. Many prominent Modernist works which fit harmoniously into the existing structure of the city and at the same time specified new directions of development for the future were realized in Lviv. Emphasizing a new beginning, this architecture avoided the radicalism of avant-garde or totalitarian ideas of holistically rebuilding or destroying what was already there. New forms and technologies were used in a way which would enable architectural modernity to become a part of the Lviv genius loci, to give a new stimulus for development, but also to avoid being directed against the traditions of the city with a centuries-old history. Not accidentally, Jonasz Sprecher’s building, despite its scale, perfectly complemented the city planning of the city centre. In residential districts, Modernist tenement houses, not blocks of flats, were dominant, and new parks, sport and shopping centres were located in a way which allowed them to accentuate the territorial development of the city, and not at the expense of the existing buildings. Modernist forms were combined with references to historical styles in the church architecture of Lviv. The most important building from the period of the Second Polish Republic, the Church of Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn, designed by Tadeusz Obmiński (1931–1934) is a specific example of such a synthesis. By the end of the 1930s, there was an agreement for new architecture, due to which in some realizations, like in the House of the Lviv City Borough Employees’ Union with a nickelodeon Światowid (Tadeusz Wróbel, Leopold Karasiński, 1933–1938), or in the Municipal Power Plant (Tadeusz Wróbel, 1935–1936) more innovative solutions based on a synthesis of simple, Cubist forms, started to be used. However, the buildings still matched the city’s specificity and the evolutionary character of changes taking place there. Therefore, Lviv remained faithful to its interpretation of Modernism, avoiding Classicist monumentalism which was popular in those years in Poland and Europe.

Modernist Lviv occupied a significant position on the map of not only Poland, but also of “New Europe” and should be classified as one of the most important centres of new architecture of the region.

The years of the Second Polish Republic brought to Lviv new possibilities of development, which were consequently used to build a modern city with an important position in the country and in the whole region of East-Central Europe. Above all, frames for the functioning of a complex city organism and the everyday life of its inhabitants were created there. Due to this fact, such distinct institutions and associations like the Artes group, Lviv photographers, poster designers, people connected with the Lviv mathematical school, universities and polytechnics, film makers, radio workers and others who contributed to the dynamic character of new Lviv could exist. On 24 June 1937, newspapers did not mention any important event from the history of Lviv, but on this day thousands of incidents, more or less significant for the life of its inhabitants, took place. These composed the everyday life of the new Lviv. From the perspective of a single day one can most clearly see that Lviv lived daily with modernity and that it was an ordinary experience which was received and accepted. As was written in newspapers, on that day the sun rose at quarter past three and set at one past eight. A mason fell o some scaffolding during the construction work at Gródecka Street and was taken to hospital by ambulance. In the Grand Theatre a spectacle called White Lady was performed. Movies were shown in several cinemas. On the radio a column by Wilhelm Raort entitled To the mountains dear brother (W góry, w góry miły bracie), a lecture on Biskupin by Józefa Vogelówna and wishes for Janeczka, Jaś and Janek were broadcast, and as a part of a Mathematics Seminar at the Lviv University Doctor Ulam presented a report concerning his academic sojourn in the United States.[7] In private diaries and reminiscences there were surely many other, more important events.

Text “Lviv and the map of modernist East-Central Europe” by Andrzej Szczerski was published in Lviv and Modernity, International Cultural Centre, Kraków 2017, p. 28-33 on the occasion of the exhibition Lviv, 24th June 1937.City, architecture, modernism organised by International Cultural Centre and Museum of Architecture in Wrocław. The text was first published in Lviv: City, Architecture, Modernism, Museum of Architecture, Wrocław, 2016.

[1] Compare: “Lwów w cyfrach. Miesięcznik statystyczny” (“Lviv in Numbers. Sta- tistical Monthly”) – a magazine published in 1906–1939 by Main Statistical Office in Lviv.

[2] E. Romer, Polska. Ziemia i państwo (Poland. The Land and the State), Kraków 1917, p. 74.

[3] K. Harasimiuk, Z historii koncepcji geopolitycznych dotyczących Europy Środkowej (From the History of Geopolitical Ideas Concerning Central Europe), „Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sectio B” 2002, vol. 57, p. 21–37.

[4] I.T. Berend, Decades of Crisis. Central and Eastern Europe before World War II, Berkeley–Los Angeles–London 1998.

[5] More about this issue – comp. A. Szczerski, Modernizacje. Sztuka i architektura w nowych państwach Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej 1918–1939 (Modernizations. Art.

and Architecture in New countries of East-Central Europe 1918–1939), Łódź 2010.

[6] Ю. Богданова, Архітектура міжвоєнного двадцятиліття (1919–1939), [in:] Архітектура Львова. Час і стилі xiii–xxi ст., ed. Ю.О. Бірюльов, Львів 2008, p. 524–570, R. Cielątkowska, Architektura i urbanistyka Lwowa II Rzeczypospolitej (Architecture and City Planning of Lviv in the Second Polish Republic), Zblewo 1998.

[7] Wiadomości Bieżące 24 czerwca (Current News from 24th of June), „Gazeta Lwowska”, no 140, 25 June 1937, p. 2. Comp. also: A. Biedrzycka, Kalendarium Lwowa

1918–1939), Krakow 2012.

Imprint

| Exhibition | Lviv, 24th June 1937.City, architecture, modernism |

| Place / venue | International Cultural Centre Gallery in Krakow |

| Dates | 1 December 2017 - 8 April 2018 |

| Curated by | Andrzej Szczerski, Żanna Komar |

| Photos | A. Fiejka |

| Website | mck.krakow.pl |

| Index | Andrzej Szczerski International Cultural Centre Museum of Architecture in Wrocław Żanna Komar |