My name is Dmytro Chepurnyi and I am a curator and writer from Kyiv. I was born and raised in Luhansk, a city that has been under Russian occupation since 2014. This publication is an important opportunity for me to reflect on a topic of great interest to me and to share my own experiences.

In my curatorial practice and writing, I delve into deeply personal experiences. In 2020, my wife Oleksandra Pogrebnyak (now a curator at the PinchukArtCentre in Kyiv) and I undertook a residency inspired by anthropologist Timothy Ingold’s perspective on landscape. The concept of the ‘Landscape As a Monument’ project also connects us to Claire Colebrook’s idea of expanding archives in the age of the Anthropocene to encompass the Earth’s geological stratification. Simultaneously, Tim Ingold suggests envisioning the landscape as an unfolding story, describing its ever-changing nature, encompassing both a steady state and a state of flux. I understand the landscape in Ingold’s perspective from the perspective of dwelling, as a constellation of all inhabitants who have ever lived in it.

I am writing this piece from Kyiv, Ukraine. Let me share with you my dwelling perspective of living in Ukraine.

In the first year of the full-scale war, I wrote a text about the village of Moshchun on the Irpin River and the first months after its liberation. This text is about a place near Kyiv where a key breakthrough and containment of the Russian army occured. This text is based on notes I took after visiting the village in April and May 2022.

What did the landscape look like upon my return? Allow me to quote the article:

On entering Moshchun, immediately after the forest you pass, there is a checkpoint. In April, the recently de-occupied village, which was on the front line near the Irpin River for several long weeks, is still being demined.. Reading holes and ruins, I try to imagine what happened here. The Internet is full of testimonies about the events. In March, when I was staying in Kyiv, I saw on the news channels an aerial photograph of a devastated village and Russian paratroopers on numerous armored vehicles storming the narrow streets. Now that I am physically present here, I see all those houses without roofs and the abandoned and broken military equipment in the middle of the streets. Paradoxically, the fact that there are almost no walls and fences left from the destruction makes the settlement a more open space for interaction with other people. Residents who have returned to the village are willing to talk and show their destroyed property. They invite others to visit the ruins of their houses. At the stop near the House of Culture, a local community center, we meet a man who turns out to be our neighbor, and he tells us about his evacuation from Moshchun in March. Later we visit him in his house. It smells of dampness. Serhii says that the scouts who lived in his house were using the double bed as a toilet and even after a round of cleaning, it is difficult for him to get rid of the smell.

The second year of the war brought a different perception of this landscape. The stench of war is still with us. But with the beginning of the liberation of Ukrainian territories, first in Kyiv and later in Kharkiv and Kherson, society gained more hope and expectations of returning home. Some have been waiting for this for a decade, others for months, some for weeks. What could be more important than such anticipation? Sometimes, however, it is precisely in such a state that hope itself can fade, reminding us of the war and what has been lost.

It is important for me to envision the de-occupation of my hometown. That is why I am attempting to write this text under great moral pressure, as a Ukrainian citizen who has not yet joined the Ukrainian army (although this may happen in the future). Contemplating the return, it is crucial to understand that the Ukrainian military, assault units, special forces and partisans will be the first on the scene, paving the way for the de-occupation of Ukrainian cities. This logic and understanding of war precedes any discussion of future reconstruction and return.

Violence in Ukraine is an all-encompassing logic brought to our country by Russia.

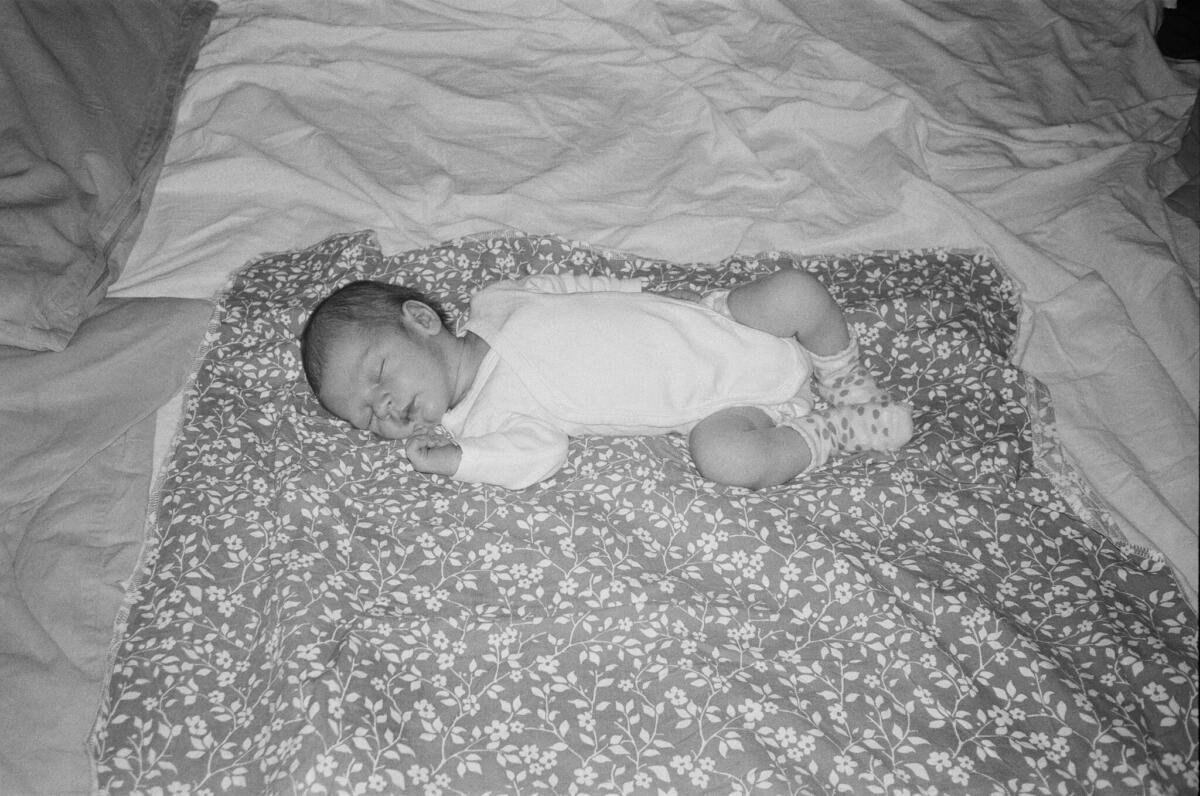

In 2023, I became a father. My son Teodor, who is just learning to speak, will soon find out about the history of the city from which his father hails. I see this as an opportunity to visit my childhood home, the garden and the cemetery. It is important for me to do this and set out on this journey. I would like my son to be by my side, to see and feel everything with his own eyes and body. The appearance of Luhansk as a landscape depends on the time of year. Silent thickets in the summer, a gray snow-covered steppe in winter. Silence says more than passersby on the streets of the neighborhood where I grew up, who recognize me by my face. How many years does it take to forget the names of the streets? How many years does it take not to recognize a person when you meet them?

As I thought about visiting the cemetery with some relatives in Luhansk I began to think about artist Alevtina Kakhidze, who created a monument to her mother in 2021, with a dedication to all civilians living and dying in eastern Ukraine today. But above all, this project is a poignant and beautiful expression that mixes personal and collective memory with reverence for the human being.

My earliest memory was when I was about four years old – a sunny street, a pile of sand and gravel, a stadium and planes flying over the western outskirts of Luhansk. Perhaps my son will also be about four and remember something similar when we return to Luhansk.

When I think of my son, whose name is Teodor, I think of Europe. Perhaps unconsciously, but my dear wife and I chose this name from hundreds of others. Teodor is a rare (in Ukraine) Greek name. Perhaps we wanted to distance ourselves from the Slavic name associated with our eastern neighbor. Teodor will probably be more proficient in European languages, especially English, as in the future he might want to pursue art. Maybe in German, to visit Germany, the country where his great-great-grandfather perished and great-grandmother was born during World War II. And perhaps in Russian, because his generation will know the Russians as people who lost the war and understood the importance of taking responsibility for their crimes.

In the words of Olena Styazhkina, a Donetsk writer who founded the think tank ‘Deoccupation. Education. Return’ at the start of the war in 2014, ‘we will all return to our cities with some projects’. For some, such project thinking will be about visiting family graves and old neighborhoods, and for others, it will involve relocating businesses. I often remind myself about this kind of project thinking while imagining a potential return home. What is my to-do list for this? What is our to-do list?

My father compares the Russian occupation to a squeezed spring that will inevitably bounce back. It has been ten years of occupation. Many acquaintances have passed away during this time. All the old neighbors died because of the lack of a quality medical system in the Russian-occupied territories.

Artist Alevtina Kakhidze is erecting a monument to her mother and all those who have perished during this long war. My colleague lost two husbands. My friend lost a partner. Thousands of people lost their loved ones and friends. What can help us accept loss and heal?

Artist Kateryna Aliynik (from Luhansk) immerses herself in the world of vegetables and agricultural heritage. She writes and paints about peas, berries, and the art of canning—traditions practiced by her grandparents in the occupied territories. The garden emerges as a metaphor for life halted by the occupation, yet it remains a symbol of hope for natural healing. Beneath the soil of the Donbas garden lie countless hidden traces of history. Bones mixed with the pieces of trees and soil.

***

As I read Aliinyk’s essay, I keep thinking: Why am I drawn to Donbas at all? Why am I interested in the hills and rivers?

As for the rest, my son will have to figure this out. But I will try to give my answer to make his search easier. Just like in the story of the devastated life in Moshchun and people’s willingness to seek dialogue with others in the toughest times, it is important to share your grief with others. We are mature enough to understand that sometimes justice cannot be found in this world – what’s lost is lost. But can we turn back time? Besides, I would like my parents to have the chance to be happy. To have the opportunity to return to Luhansk in their lifetime. Will it be the same place they left ten years ago to escape the occupation? Hannah Arendt writes in the text ‘We Refugees’ about the unspoken desire of refugees to assimilate, to become the greatest patriots in their new homeland and to forget everything they belonged to. I think she is right in her criticism.

Dear Son, it’s impossible to forget a city lying in ruins. No matter how many shoes you change, the ashes under the soles will be remembered. There are about 40 million refugees in the world and they all need care. I am drawn to Donbas because I am looking for solidarity. It is important for me to reflect and imagine the de-occupation – because our odyssey is not yet over.

We will be welcomed home by neighbors, old friends, thickets, overgrowth and bushes. The landscape after de-occupation bears traces of destroyed life and altered living conditions. The liberation of cities is accompanied by the fear of their destruction.

I imagine that Luhansk’s Guernica may be created by Kateryna Alyinik as a mix of soil and traces of our former lives.

If we consider the politics of memory in the occupied proxy republics, it becomes apparent that, alongside commemoration dictated from above, a local mythology has emerged over the years of occupation. This mythology often originates in the imagination of the neo-feudal leaders of the DPR and LPR. The question arises: what will preserve the memory of what happened in these cities after liberation, when the monuments to the occupation have been dismantled? I contemplate how to depict abandonment. I am thinking about rhizoma depicted by Kateryna Aliinik, under the ground surface where mixed up bones and ruins lie.

So how will we see the landscape after a long occupation?

An ecological disaster, mined territory, a demographic change (the loss of the male population in the war), the emigration of young people. Will everyone who belonged to this land return to live here? Personally, I will not return to live permanently, and neither will most of my generation. But perhaps we can create conditions for those, who dream of returning, and those, who dream of rebuilding, to see their ‘return projects’ through, following Olena Styazhkina’s vision. What can be better than the hope of a future return and the confidence that it will happen one day?

What future can the region have? Today, the future has already come. My region is a battlefield, and it will remain war-torn for decades. To quote George Steiner, who described post-war Europe in terms of ‘absence’, Donbas has become a place where many people are absent. Lives, environments and erased histories destroyed by Russia.

Empty industrial complexes: factories, warehouses, workshops. What fills this absence? Troops deployed on both sides of the front. The military has become a new working class. Soldiers – the new miners. Should we hope that this will change and that Donbas will no longer be a symbolic wall against Russian aggression? Most likely, the protruding eastern peninsula will be a place of defensive infrastructure even after the war.

Please support Ukraine and its citizens in their efforts to reclaim their territories. Your support brings hope for return and justice.

The text titled ‘Landscape after Deoccupation’ was originally presented as a speech by Dmytro Chepurnyi during the ‘Paysages de guerre / War Landscapes’ conference at Lille University, France, on October 20, 2023.

Return to the table of contents and Introduction.