Competitions are an inherent component of the artistic system and it is actually difficult to even imagine the art world without them. They establish hierarchies, elevate individuals, offer chances for artistic discoveries, and, quite unavoidably, at times lead to controversy. Some of the European competitions were the actual driving force behind new artistic phenomena. That, for instance, was the case of the Turner Prize and its influence on the reception of Young British Artists. Having at least one highly regarded competition is also significant for particular local scenes: it is a factor, it could be said, which certifies their importance and stage of development. In light of all that, it is worthwhile to examine what the competitions in Central and Eastern Europe are like, and what kind of message they actually convey. What art do they exhibit? What are their objectives? When were they created and who are they ran by? It is an interesting enough moment for that kind of reflection, since we just recently witnessed the widely-commented manifesto of this year’s finalists of the Preis der Nationalegalerie, announced on September 29th in the Hamburger Bahnhof, who protested against both the organisational policy of the competition, and the media reception of the whole event. The criticisms expressed by the participants of the competition for Germany’s most prestigious prize do not at all seem a singular act: looking at the events surrounding competitions in Central and Eastern Europe, and at the very form of those competitions, it is hard to overlook an accumulation of problems. Their formula seems ever more worn-out, or, alternatively, the competitions are eaten away from the inside by internal conflicts which may one day result in an open rebellion. The latest competitions in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland did give us reasons for concern.

Formalisms and the moderate politicisation

The Czech Republic’s most important prize is named in honour of Jindřich Chalupecki, an eminent and truly legendary art critic. It is awarded to Czech artists under 35 years of age. The event was originated back in 1993 on the initiative of Václav Havel, Theodor Pištěk and Jiříe Kolář, and is organised by the Jindřich Chalupecki Association which grants to the prize-winners an amount of 100.000 Czech Crowns destined for financing an exhibition and a catalogue plus a six-month-long residency in New York. The finals of the Chalupecki Competition take place in turn, either at the Prague National Gallery or at the Moravian Gallery in Brno. Besides the exhibition, however, the Chalupecki Foundation holds numerous additional displays in order to promote the art of the finalists and the prize-winners. I can, for instance, remember the amazing Silver Lining show held two years ago at the National Gallery of Prague where works of a number of Chalupecki prize laureates were displayed. What made that particular show rather exceptional was the decor created by Dominik Lang, a laureate himself. Its central motif was the egg figure and its variations: raw, smashed, hard-boiled, fried… Silver Lining was a show widely commented in the Czech Republic, whereas Lang’s decor was deemed by many as too radical and overshadowing the works of other prize-winners. And yet, it was a show I don’t think we could see in Poland.

Visiting Prague this time, on the other hand, I came across the Ripple Effect show at the Futura, where visitors can also see works of the Chalupecki competition participants, but in this case: of those who’ve never won anything there. Still, thanks to the outstanding meticulousness that went into the preparation of the show and to the rigorous selection carried out by curator Karina Kottova, it was barely possible to notice that one was at a “looser” exhibition. Strolling down the hallways of the Futura I rather felt as though I was visiting another edition of Not Fair or some other event of that sort: a youth and avant-garde art fair. That impression lasted even after I could confront it with the finalists’ exhibition I saw in Brno. The moment I entered the exhibition I was handed an aesthetically produced shiny booklet containing essays on the competition participants, documentation of the exhibition and a map-guide which not only informed about the attribution of particular works, but also contained indications on how to interact with each one of them: e.g. explaining which one I could touch, sit on, smell, etc… The competitors’ exhibition took up the entire surface of the ground floor. Each finalist was given one or two rooms which slightly varied in terms of decor. One of the most memorable rooms was the pinkish boudoir where Romana Drdova’s sculptures were exhibited: sculptures mostly consisting of ready-made everyday objects present in our daily routine. We could therefore see smartphones, a glass bowl filled with a semitransparent liquid, some sponges, tubing, enigmatic forms made from Perspex, rubber wheels, hard-to-define pink mass shapes… The impression of being inside a girl’s bathroom was completed by a round mirror which seemed like it invited us to take a selfie.

Richard Loskot, another Chalupecki Competition finalist, roughly followed the same direction. Inspired by the very building of the gallery, which was once a private palace, he turned his two rooms into a bedroom and a salon. There was an aesthetic sofa we could rest on, an invisible canary which sang in its cage, and a cat lying on the carpet which would, every now and then, appear in the mirror. All that was arranged with a clear plastic sense and a good dose of humour, and yet the overall aesthetic seemed similar to that of Drdova’s works. And that was not the end: all those for whom the boudoir, the salon and the bedroom were not enough could go on and lie down on the sofas painted by Viktoria Valocka, an artist who is especially keen on using old worn-down fabrics. And so, Valocka will paint on old bed sheets, but also on fading sofa upholstery. The old tacky upholstery pattern then becomes a charming underlying canvas. This time, the theme of her semi-abstract paintings were the tropics. Exotic scenes and landscapes appearing in several places reflected some of the artist’s actual travels, e.g. to Israel. Valocka’s style is best captured by the description in the catalogue which itself, beginning with the very first words, seems contradictory. It is difficult to mistake this artist’s style for anything else, but at the same time it does bear resemblance to Tashism- and informel-inspired works, or to those by the Czech surrealists. Valocka follows the popular tendency to take interest in materiality. All in all, put together it all seems to sound like a definition of zombie-formalism…

I must confess that for me the walk through the Moravian Gallery was a weird experience. The exhibition, so meticulously laid-out and produced, seemed more like a show a commercial gallery would come up with, and not so much as a competition stage where personalities, concepts and artistic strategies would contend.

A form of escape from all those items, sculpture-like things and slick bourgeois-aura-projecting installations were the films by Dominik Gajarski and Martin Kohout. Watching them, by the way, also meant a chance to drop on some comfortable furniture and unwind. Gajarski’s film Equlibrium was an opportunity to look at humans through the eyes of animals or, more precisely, from the perspective of their concealed thoughts. Martin Kohut chose to focus on mankind, particularly on the forms in which it functions and on the kinds of bonds it creates. Slides tells the story of Asla and Bora, a modern couple who communicate in a rather unusual way. Since one of them works during the day and the other at night, they stay in touch by leaving one another memos and notes. Kohut’s poetic film of oneiric ambience is arguably the most convincing work of all those presented at the exhibition: here at last one could find an issue worth reflecting on. It is presented in a somewhat refined way, but unlike many other works here, it does not have a whiff of formalism about it. And probably thanks to that very trait this work turned out to be the winner of this edition of the Chalupecki competition. The runner-up prize went to Loskot.

I must confess that for me the walk through the Moravian Gallery was a weird experience. The exhibition, so meticulously laid-out and produced, seemed more like a show a commercial gallery would come up with, and not so much as a competition stage where personalities, concepts and artistic strategies would contend. From my perspective, speaking as a Polish art critic, that visit was also like a journey back in time, to the moment two years ago when PIS only just came to power, and the artistic circles would still discuss things such as new materialism, the turn towards objects or the already mentioned zombie-formalism. Now, the Polish artistic society has adopted a sort of fixation on the issue of Polish identity, and the curators, depending on their private views, tend to either critically analyse it or to elevate it. This, obviously, is to some extent an unbearable situation. These days, when the government implacably implements the policy of isolation, Polish art, it would seem, has taken up a somewhat similar tactic of inbreeding. Our Czech neighbours so far do not have such problems, and if the Chalupecki exhibition is anything to go by then the current trends in Czech art can be defined as well-groomed, pleasant and refined. The finalists of the Chalupecki competition seem to be perfectly proficient at using the international language of art, and they tackle global issues. They do so, however, not remembering that the local perspective can be interesting too, no matter the times and the political atmosphere. Without the local factor, the global approach is just an empty form.

Since I am on the subject of the atmosphere inside the Polish artistic circles, it is worthwhile to add that its clear manifestation was this year’s edition of Spojrzenia, Poland’s most important competition for artists, organised by the Zachęta National Gallery and Deutsche Bank. Compared to the extended paraphernalia surrounding the competition organised by the Jindřich Chalupecki Association, the formula of Spojrzenia seems rather monotonous and overly modest. There are five finalists who each year have at their disposal the same two sterile rooms at the Zachęta gallery. The exhibition’s biggest attractions are the vernissage and the verdict announcement which takes place several days later. After the latter, selected guests move on to a VIP banquet. Seeing all that from the angle of an ordinary visitor, it is hard to find it exciting. No wonder then that the people interested in the competition are mostly the artistic circles themselves, each year repeating the ritual of complaining about the jury and the organisational details. What gives those backstage chats some juiciness is the fact that the general ambition of Spojrzenia is to map Polish art and define its up-to-date condition. The jury of the latest edition, clearly impressed by the right-wing turn in Polish politics, decided to praise those engaged artists who had taken up a critical approach towards the Polish reality. It is disputable whether or not an event sponsored by a German bank is the right place for such political manifestoes. The works presented at this year’s edition seemed somewhat forced. And not risky. Some of them even, like Ewa Axelrad’s installations, narrowed the issue of policy to design. The main prize this time went to Honorata Martin, quite tellingly for: “consistency in creating relations based on affirmation, not on antagonisms”. The most radical artist at Spojrzenia, Łukasz Surowiec, lost his battle against the distinguished institution which is Zachęta. His original project to hold a competition and single out Poland’s most economically excluded citizen was deemed unethical by the exhibition’s curator Dorota Monkiewicz. It also soon turned out there would not be sufficient funding to hold it. Surowiec, then, went on to carry out his second project: a boutique with fashion for protesters. That, compared to his earlier projects, turned out rather anodyne. It looked like Surowiec was not the only one who had trouble adjusting his vision to the curator’s preferences and to the institutions which, in this case, instead of helping artists tried to hold them back as much as possible. The final result of such curatorial activities was, in general, discouraging. And that thing the audience saw was supposed to be the radical face of Polish art. Well, if that is the case, it really would be better to simply go back to the old and safe new materialism. By contrast, where we did see what a truly radical competition can be was at last year’s Innovatsiya. Its jury chose to give the main prize to Piotr Pavlensky for setting on fire the entrance to the Moscow FSB headquarters. For that very reason the Russian authorities got rid of the competition. That is the cost of genuinely getting into politics.

Revolt of the artists (and curators)

Those who are bored watching the pseudopolitical declarations of conservative institutions or the hipsterism of the artistic glitterati should go to Slovakia where, albeit not for reasons that would make the local artistic circles happy, genuine artistic rick is indeed sometimes taken. That is the reason for some commotion recently surrounding the Oskár Čepan award, Slovakia’s most important competition for young artists, organised by the Nadácia Contemporary Art Centre (the name is somewhat misleading: it is an NGO, not a state institution). The history of the award is complicated and the problems begin with its very name. Oskár Čepan, after whom the event is named, was first and foremost a literary critic, so it is dubious if his name was adequate for an award presented to visual artists. The competition, held since 1996 and at first called the Slovakian Young Artist of the Year Award, at some point began to lose significance and cachet. Zuzana Pacáková and Christian Potiron then ventured to revive it. The competition, up to that point always organised in Bratislava, began to travel to different cities in Slovakia. On the one hand, it was due to the lack of adequate exhibition venue in the capital, on the other: it was a gesture of support towards smaller hubs. The competition organisers also have the ambition to allude to the history and specificity of the cities hosting respective editions. That is usually reflected by occasional events organised within the Čepan Weekend. This year’s edition, for example, was held in Nitra, a city of interesting theatrical traditions, and so: during the Čepan Weekend one of the debates was dedicated to the subject of intermediality in art. The debate itself, by the way, was not very engrossing, held in male-only configuration and only in Slovakian. A discussion which, to my mind, was much more absorbing was the one about a new prize awarded by Nadácia, one designed for young art critics. The Contemporary Culture Academy Award (Akadémia Súčasnej Kultúry, abbreviated to ASK) is meant to enliven the, passive and modest in terms of numbers, circles of Slovakian art critics, and to help promote new talents. The idea does not seem bad (by contrast, the Polish Jerzy Stajuda Art Critics Award, co-sponsored by Zachęta, is now given not to critics, but to curators, and among them: to the employees of Zachęta itself, so it is hard to see any sense about it anymore), although I must say I was surprised by the stipulated age limit. In Slovakia, it turns out, “young” means “under the age of forty”. Interestingly enough, a similar limit was stipulated for the Oskar Čepan prize. I later managed to learn that the decision was taken in response to the expectations of those slightly older artists who, despite being important for the Slovakian scene, were not eligible for the prize.

The venue-changing, travelling competition for young and youngish artists turns out rather interesting when compared to other Central-and-East-European events. It looks like the reforms introduced by Pacákova and Potiron are appreciated. The potential critics now have a hard task: after all, not so long ago the situation was far worse. So why complain? That was the very argument faced by this year’s finalists of the Oskar Čepan (Katarína Hrušková, Nik Timková, Zuzana Žabková, and the APART collevitve) who jointly, days before the inauguration of the exhibition in Nitra, published in Artalk.cz a latter in which they expressed their disappointment with the prize and announced they would hold a joint exhibition without divisions into particular authors’ works. The finalists’ letter contained no specific accusations, so it was quite natural to assume that what we saw were just (as I was told by a number of people): “unjustified criticisms from spoiled kids”.

And yet, the concept of the rebellion and the collective exhibition does seem very interesting, also because of the differences between the finalists’ profiles. Katarína Hrušková works with photography and literature; she approaches both those disciplines from a performative angle, and sometimes turns them into performance art. Zuzana Žabková is a choreographer and a dancer who also uses the language

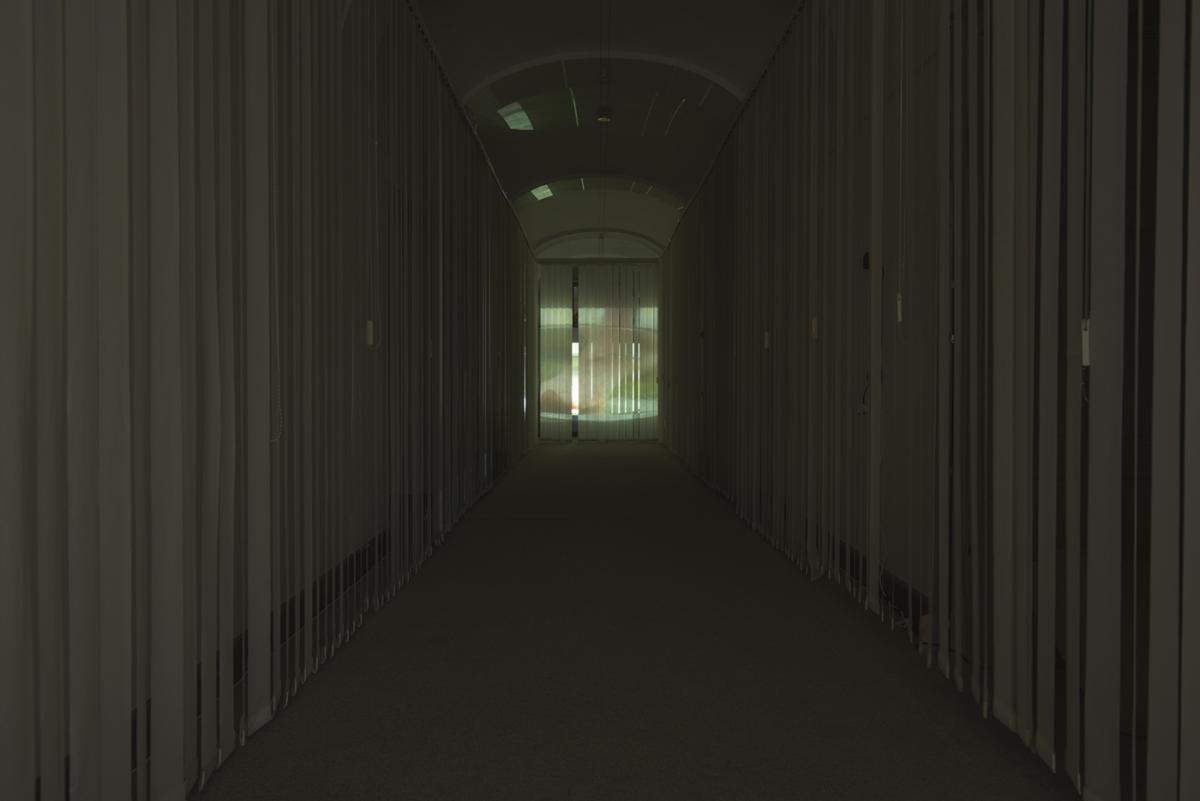

of installations. Nik Timková, on the fence between visual arts and music, draws inspiration from the underground culture of the 1990s and produces works reflecting mystical, post-Internet poetics. And then, there is the APART collective, comprising four members (Magda Scheryová, Andrej Žabkay, Denis Kozerawski, Peter Sit) and active both in the field of art and in curatorial work. Who knows, perhaps it was this very ability to sit between those two fields that made it possible for them to come up with a surprisingly coherent show which really did look like a single-artist exhibition. As they later explained, the idea of the joint exhibition only came to them after some time, when each artist already had a draft of their work (before the final exhibition participants are each given 1000 Euros and are required to come up with new works). When the finalists saw each others’ projects, it turned out there were many common elements. Another integrating factor was the ever-intensifying conflict between the artists and the event officials which, as it later turned out, was mostly due to communication problems. At a certain point of the preparations, the artists were left alone. The competition coordinator, who was expecting a baby, was taken to hospital and remained unavailable for the next two months. Meanwhile, the foundation chairman Christian Potiron with his small team could not handle all the organisational issues. It seems he too was unavailable for a long time, and when he eventually did come up with an administrative e-mail he blamed the situation on his subordinates. The lack of communication is well illustrated by the fact that the chairman did not know what was actually going to be shown at the exhibition. He was adamant that the artists simply exhibited some of their older works, having previously misappropriated the event’s money. In light of all that an interesting question arises: if no one was in charge of supervision, how did the exhibition even come into being? Perhaps such situation was, after all, favourable for the artists? No one controlled them or tried to instruct them on what was right or wrong, unethical or too expensive. And so, they managed to come up with a decent exhibition, brilliantly adapting the difficult (and let’s be honest: boring) space inside the Nitra gallery.

The venue-changing, travelling competition for young and youngish artists turns out rather interesting when compared to other Central-and-East-European events. It looks like the reforms introduced by Pacákova and Potiron are appreciated. The potential critics now have a hard task: after all, not so long ago the situation was far worse. So why complain?

The gallery building in Nitra is enormous, its interior recently underwent a renovation (spectacular, eye-catching stylistic mixture of historical design and art deco), and yet the exhibition space dedicated for modern art is surprisingly small: four tight and low rooms with cheap mosaics and fitted carpets on the floor. The artists additionally took over one of the staircases. There, they exhibited the one work which was an actual collective effort: a board listing adjectives referring to the Čepan competition (most of them wishes, really) which were repeated in an audio loop from a concealed sound system, and echoed all over the empty staircase. And so, the artists thought the event should be professional, self-critical, realist, stimulating critical thinking, efficient, progressive, context-aware and self-aware, open for dialogue, empathic… et cetera. Since turning that entire list into reality is nigh on impossible this collective work should rather be seen as a bit of speculation about utopia and a thinly veiled message that the current Čepan competition doest not meet the listed criteria.

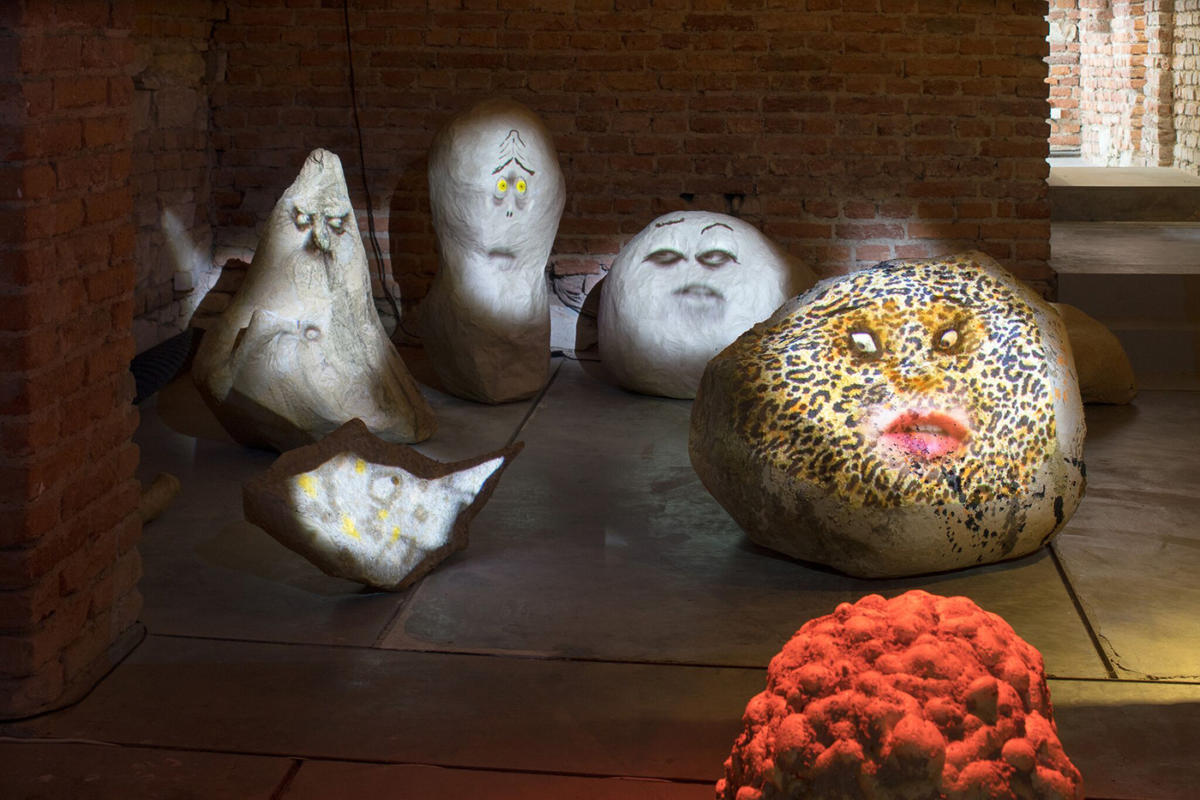

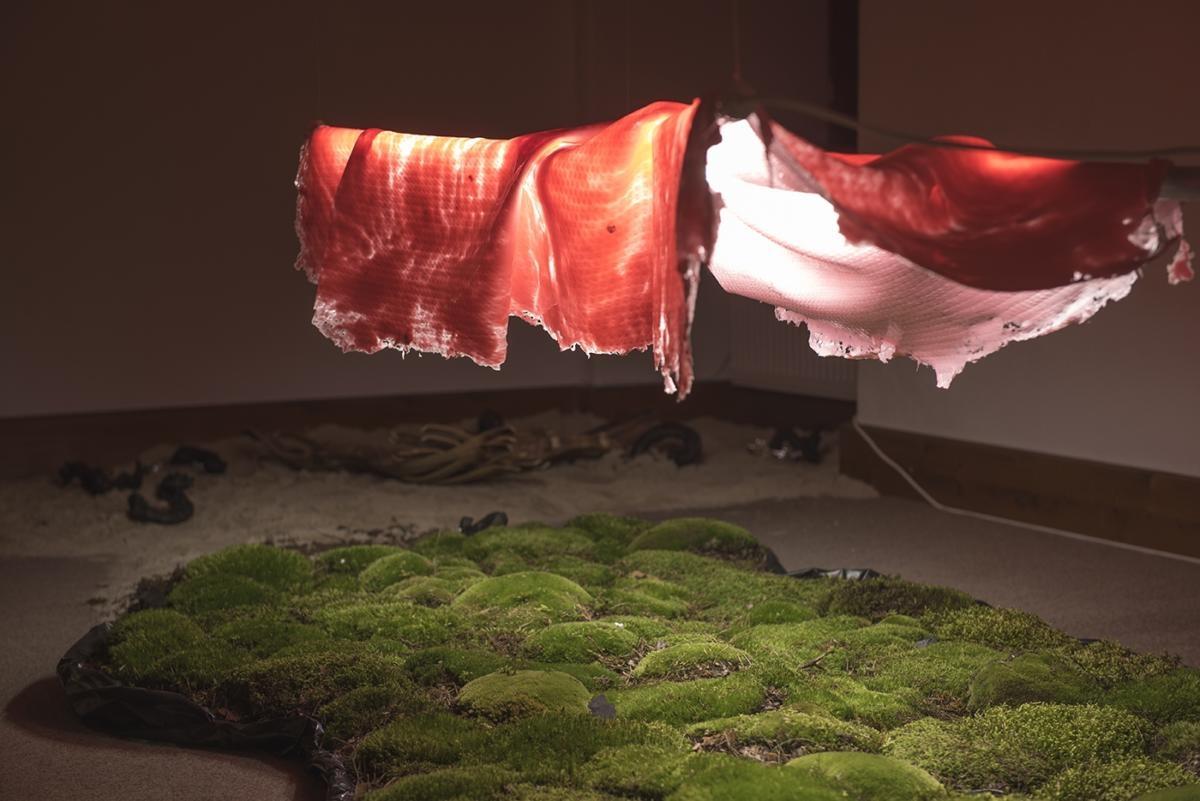

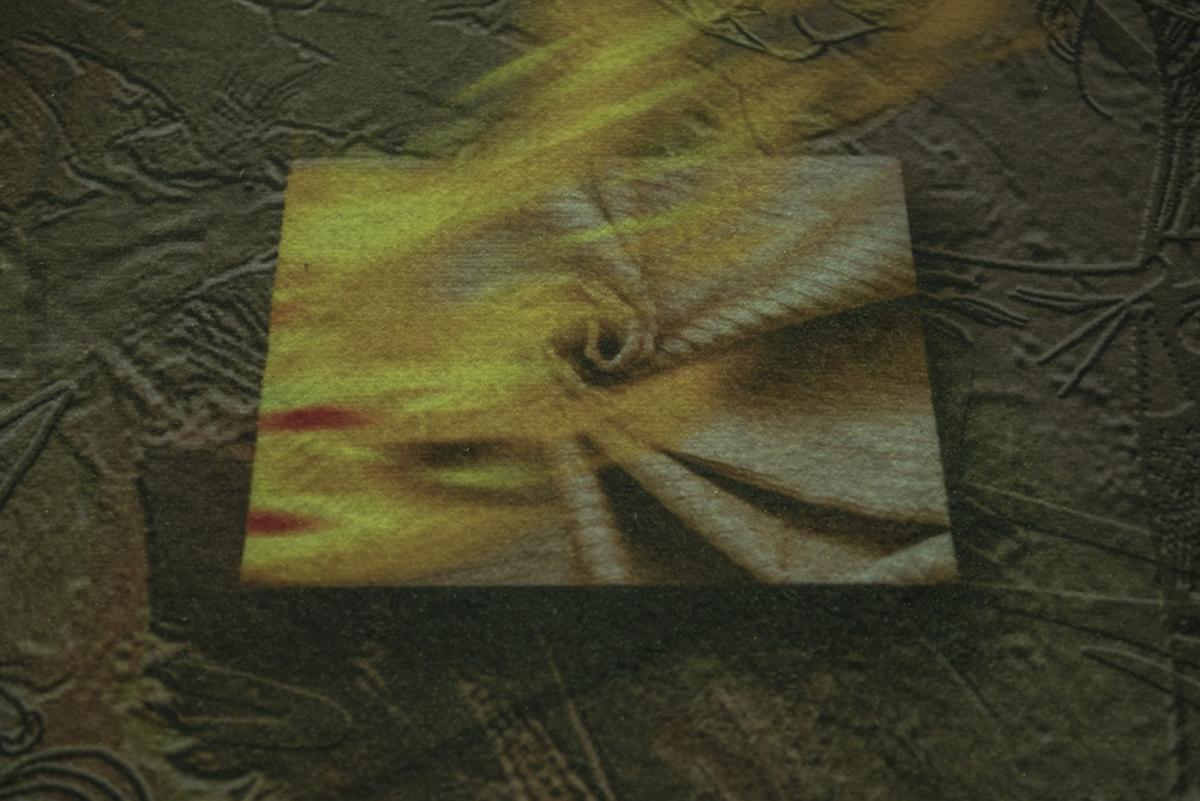

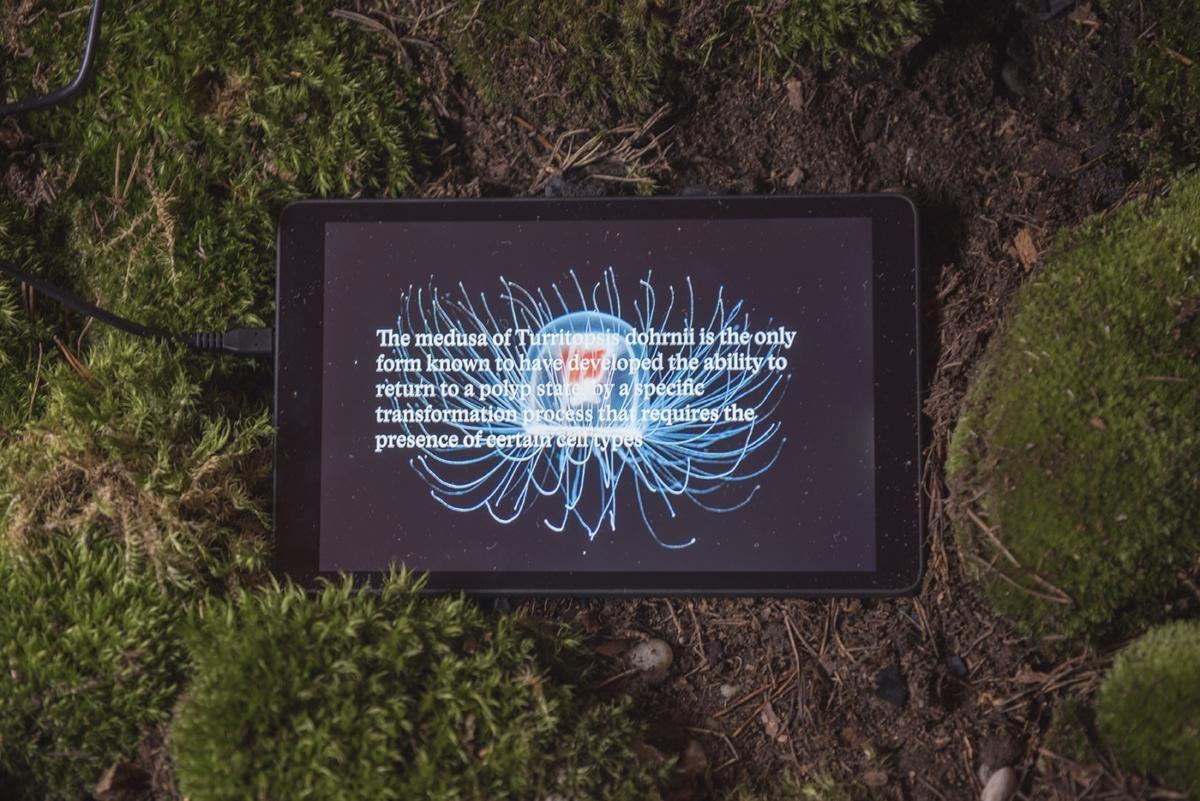

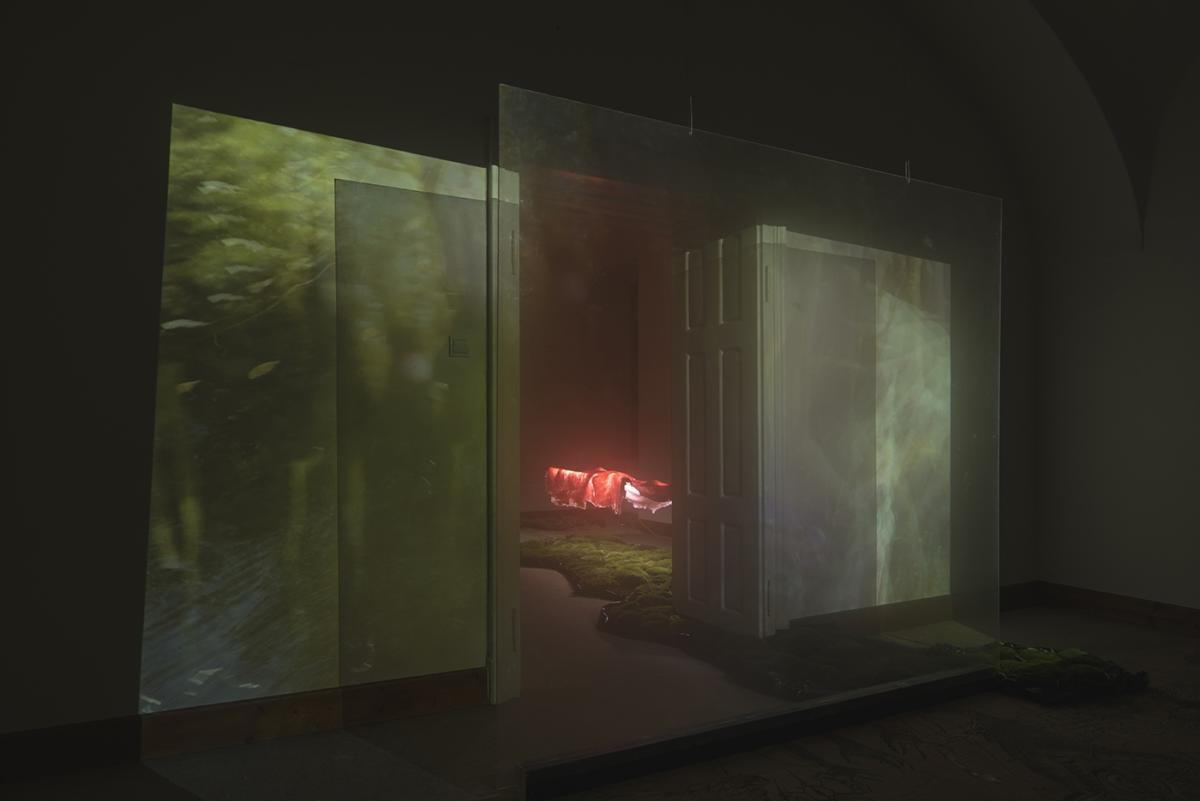

As though designed as a compensation, the actual exhibition took form of a therapeutic grotto where biomorphic shapes were mixed with something resembling prehistoric remnants with modern intrusions. At the entrance the visitors were welcomed by a large illuminated board resembling a slice of meat levitating over an islet of moss. As I later learned, it was a work by the APART collective put next to Nik Timkova’s plush forms and Katarína Hruškova’s rocks, a leitmotiv present in her art. Another attention-catching component were all the skilful allusions to the venue’s character: Tímkova came up with a Palaeolithic-tribal carpet, and Hruškova hung one of the rooms with blinds brought from all over the gallery, thus creating an amazing backdrop for her voiced-over poetic stories and for the final piece in this puzzle: Žabkova’s film showing her foot immersed in a bowl of water.

I must confess that on my way to Nitra, when I tried to imagine what the manifesto-like politically subversive joint exhibition could look like, I pictured something different. At the Nitra gallery we will find relatively little clear messages or explanations (the only actual diagnosis of the situation is the already mentioned board): this exhibition-turned collective manifesto of united artists mostly operates on the level of form and intuitive actions, interpretable from the aesthetic and emotional angle. It is a very subtle form of rebellion, and yet it turns out much more interesting than both the formalism-dominated Chalupecki competition and the Polish Spojrzenia, supposedly critical, but in reality just politically correct.

Specific organisational problems which were not reflected in the artwork were, by contrast, commented on by the artists themselves as they gave the audience a guided tour of the exhibition. The tour then turned into a heated debate. To round their manifesto off, the artists once again listed their demands and doubts during the award ceremony, already after the verdict: a verdict which, by the way, proved very favourable for them, since the international jury (Lily Hall, Barnabás Bencsik, Dorota Kenderová, Michal Novotný and Kiki Petratou) decided that the main prize, comprising of money and a residency in New York, would go jointly to all the finalists. It would now be up to them how to divide the funds and who to send on the trip to the US. According to the verdict justification, the jury appreciated the energy born between the united artists and at the same time wished to stress the importance of the date: the previous day, November 17th, saw the 28th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution.

The artists accepted the prize and chose to send Hruškova on the residency. It was her, reportedly, who most dreamed of going. A question cold be asked, if the finalists should accept the prize at all, since they contested the competition as such, but they say they saw it just as remuneration for their work. That much is undisputable: they did some. In that sense their criticism of the event was not absolute: after all, it did take place, the exhibition did happen, and all the expected guests went to the ceremony.

The end of the scandal story at the Oskár Čepan competition seems optimistic. The one troubling question that remains is: what (if anything) will become of all that? One of the problems connected to the competition, and at the same time one of the reasons for the conflict, is the lack financial stability. When organising the event, Nadácia is dependant on grants from the ministry. In order to even survive it has to apply for them every single year. That makes it virtually impossible to take a gap year and rethink the formula of the event, a thing some have suggested to the organisers. The people behind the competition work in precarious conditions. Their team is too small and in order to make ends meet most of them probably need to do other jobs. In light of that, the accusations of lack of professionalism may seem unfair. And they certainly angered Potiron who, by the way, is trying to pass himself off as the victim of the situation. It was clear to see during the Sunday debate with the artists, meant as a summary of the Čepan Weekend: it was him, poor thing, heroically struggling to keep the, undoubtedly valuable, event afloat while having for adversaries the entire ever-complaining Slovakian art community, unable to give him credit for his sacrifices. What if he just quit the job? What would then become of the event? Potiron’s arguments may contain a grain of truth (the harum-scarum preparations of the event are probably rather unpleasant), but on the other hand they are almost tantamount to blackmail and cannot justify some of the organisational slip-ups (after all, two months is sufficient time to write hundreds of e-mails, let alone one). The team behind the Oskár Čepan competition could definitely use some work optimization, but we cannot be sure that will happen. Meanwhile, grant applications have already been prepared and Nadácia is seeking a new competition coordinator having concluded that the previous one has clearly burnt out.

The latest editions of Spojrzenia, Chalupecki and Čepan have shown us that it is worthwhile to rethink both the working conditions offered to artists (remuneration, technical assistance, prizes, etc.) and the quality of cooperation between artists and institutions: it should be reflected in the latter caring about the interest of the former, not the other way round.

What happened in Nitra will most probably go down in the history of Slovakian institutional art criticism. Also on the scale of the entire Central-and-Eastern Europe region it seems like something unprecedented. And yet, boredom with the competition mechanisms is noticeable in other countries too. In Poland, it has been expressed by three young curators, Aurelia Nowak, Romuald Demidenko and Tomek Pawłowski who this year undertook to organise the 8th Youth Triennial. The event, held since 1992 and organised by the Sculpture Centre of Orońsko, has long left its best days behind, but thanks to the revolutionary approach of the curatorial trio is now again earning interest. The idea for refreshing the formula here was indeed radical and basically consisted in getting rid of the competition and substituting it with a week-long symposium. The curator’s original plan even proposed giving up on the exhibition: after the symposium the rooms were supposed to remain empty. However, since the curators chose to give maximum liberty to the artists, in 24 hours, with no budget whatsoever and contrary to the original idea an exhibition did come into being. It was somewhat chaotic, in places barely justifiable, but as a whole, rather amusing (we could, for example see, the brought-over study of the Centre’s head, Eulalia Domanowska, the beds on which the artists slept, and an unusual collection of filthy dirty plinths from the Centre’s storage). Some of the triennial’s participants complained that there was so much liberty that it turned into organisational chaos, and that some of the curators were more focused on their meals than on producing some critical discourse during the symposium. Still, the message generated by the event as a whole was clear: people are fed up with traditional-form competitions, time for change has come. We’ve had enough of using artists and beguiling them with promises of fame and success, enough of precarious conditions and exploitation in the name of art. During the discussions the curators of the Triennial openly stated that rather than in art they were more interested in people, the relations between them, and their work methods. An interesting perspective, albeit perhaps too radical: both in life and in art, what matters besides the process is the final result. And that latter component in the case of the Orońsko Triennial could seem dubious (it certainly did not impress the head of the Sculpture Centre who remained sceptical until the very end of the latest edition, and suggested to the participants they started reading books).

The general concept of event evolution proposed by the Orońsko curators, based on the idea of getting rid of the competition as such, is rather hard to accept and, in the long run, not that good. Competitions still are, after all, a source of measurable benefits for the artists and for the artistic scenes where they take place. Another thing, however, is to rethink the conditions: here a lot can be done. The latest editions of Spojrzenia, Chalupecki and Čepan have shown us that it is worthwhile to rethink both the working conditions offered to artists (remuneration, technical assistance, prizes, etc.) and the quality of cooperation between artists and institutions: it should be reflected in the latter caring about the interest of the former, not the other way round. Another factor is working on the formats, opting for developing and changing the competitions, so that we do not witness similar shows every one or two years. The rather interesting situation that took place at the Čepan Competition shows us that faith in rituals involving a single artists preparing a single artwork is pure fiction. Sometimes, a much more interesting and creative outcome can result from collective efforts and, as I mentioned before: from being ready to take risk and come up with something politically incorrect or not following the popular, worn-out artistic trends. Last but not least, when reflecting on the competitions held in Central and Eastern Europe it behoves us to ask if giving them national profiles is interesting in the long run. Each country needs its own competition. Trouble is, though, that such events only attract the local art circles. That, in case of the peripheral scenes of Poland, Czech Republic or Slovakia, is beginning to feel tiresome. The example of Agnieszka Polska, this year’s winner of the Preis der Nationalegalerie, illustrates what kind of aspirations artists from the Eastern block can have, and which competitions can actually make one recognisable. It would probably be difficult for the events from the less developed scenes to compete in this respect, but still there seems to be a lot of room for improvement. It is enough to believe that change can actually be introduced.

This article was written as part of the East Art Mags residency programme, in partnership with Magazyn SZUM and Artalk.cz. The programme is supported by the Visegrad Fund.