As Slovenian philosophy pop-star, Slavoj Žižek tends to repeat, today that we will have to change our social and economic system, but what really matters is how we change it. Kinship, when understood as blood relations and manifested in a nuclear family model, is by far the most common, viable and accepted social structure in the Western world. At the same time, it is a structure whose flaws have been a topic of discussion in progressive circles for years. Unruly Kinships aims at inspiring our imaginations to consider how we can replace bloodline, heritage, or marital kinships with the process of kin-making – building relations and a sense of belonging outside of family bonds.

Invisible communities

Just as we enter the Temporary Gallery exhibition space we may be surprised by how diverse and unexpected are the ways of addressing the main topic. While it is difficult to determine one trajectory of thought common to the contributors, a few recurring motifs are recognizable in the artworks. One of them is the matter of visibility. The first piece we encounter is an audio work Muck Acknowledgements by artist and musician Geo Wyex. In the form of a remix based on hip-hop shout-outs, he calls names of people, objects, and lands. His piece creates an ambience. With sound sources hard to locate, it suggests from the very beginning that visibility is not an indicator of validity. Keeping this in mind, we move on to the next work on display, made by a group of sex workers in Rome. Together with the artist Pauline Curnier Jardin, they established Feel Good Cooperative – a space for support and expression. It is a substitute union for those who cannot officially unionize, a platform providing collective protection. This is a vivid example of a situation where visibility really becomes an issue. Being a sex worker just next to the Vatican pushes this already marginalised group to the extremes of exclusion, forcing them into almost complete imperceptibility. The Death of the Pope consists of a video documenting moments just before pope Benedict XVI’s funeral and a series of drawings inspired by this event. All proceeds from the sale of these sketches goes to supporting the group’s members.

Speculation in practice

Several artists have taken it upon themselves to demonstrate alternative forms of family and coexistence, by turning speculation into action. One example is the film Denim Sky by Rosalind Nashashibi, in which a camera followed her, her kids’, and her friends’ daily life over the span of four years. As we watch their journeys, both real and conceptual, we witness how an expanded nuclear family model can function in practice. Even though care work is not the central topic of the piece, the saying ‘it takes a village’, in reference to raising a child, comes to my mind immediately. Denim Sky shows how replacing conventional social structures in favour of fluid, spontaneously constructed communities can bring new qualities to the lives of both adults and children.

Playful disruptions

Nashashibi’s film, which is over an hour long, is counterbalanced by three other artworks that also address the topic of family in an experimental way – but not exactly seriously. Selma Selman, an artist and activist of Roma origin, whose artistic practice I consider greatly refreshing, staged a performance and installation where she and men from her family extracted gold from the parts of electronic/computer waste called ‘motherboards’. The precious ore, obtained from seemingly worthless objects, will be melted down and made into earrings – a gift for Selman’s mother. Similarly ironic, Jay Tan’s installation TANS/ANTS/TANS/ANTS reminds us how arbitrary bonds can be. Using various modeling materials as well as toilet paper and wood from trees from Rotterdam, the artist created a large sculpture resembling a landscape model or a gaming environment. Between rocks and meadows made of polymer modeling clay, he placed figures of famous people – a DJ, a professional poker player, a golfer and a piano composer – who have nothing else in common besides their surname, which also happens to be shared by the artist himself. The viewer is left with the feeling that the traditional signifiers of filiation can artificially create relations which do not exist outside of the hereditary realm. But is it a good or bad thing?

Another approach to playing with family structures by setting the traditional hierarchy upside down was a performance by Krõõt Juurak, her partner Alex Bailey, and their son Albert Bailey Juurak. The director, five-year-old Albert, conducted the performance in the gallery space by telling his parents exactly what to do. However, the performed gestures were not the focus of the piece, but rather the pure fact of a child being the driving force behind them. The whole idea is on the one hand derived from appreciation for the disruptive potential of such actions, but on the other – strictly practical. It is the simplest way of combining artistic work with childcare; a way to both have fun deconstructing grownup, established paths and also to feel what it means to be parented.

Nothing is for granted

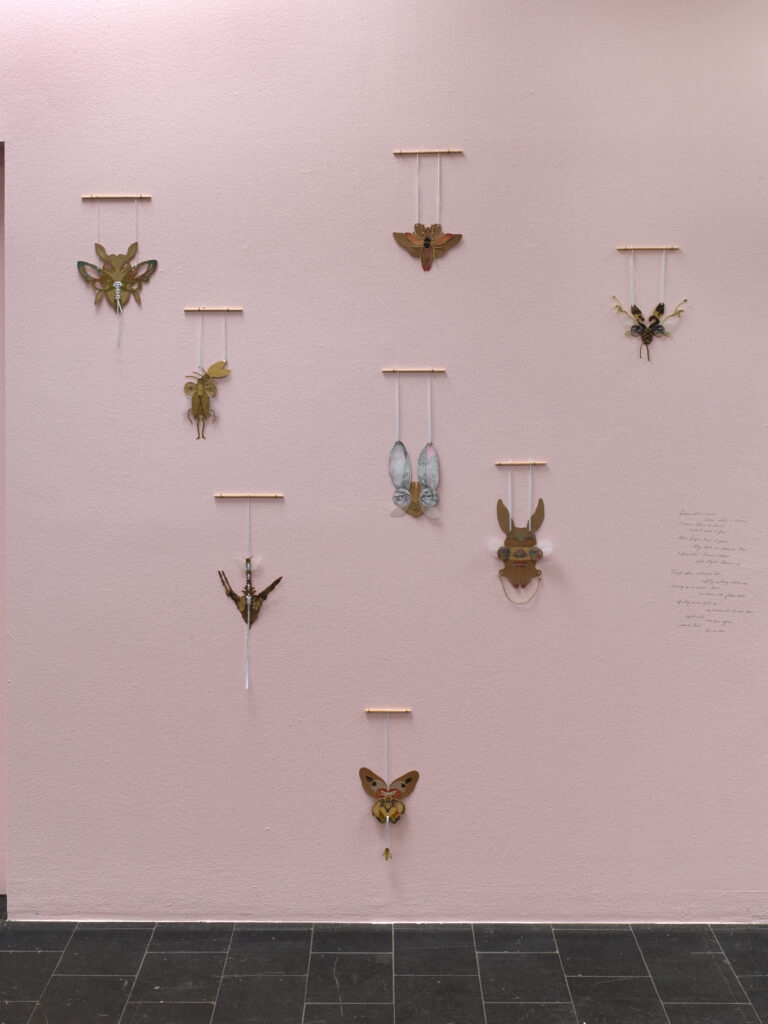

Two other artworks worth a closer look concern the fragility of close interpersonal relations. Lena Anouk Philipp’s mobile sculptures were made during quarantine caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. The artist created several paper pieces consisting of flat parts to be assembled into spatial objects. She sent them to people with whom she wanted to reconnect. With this tangible gesture, Philipp employed the gift economy as a way of strengthening relations in times of isolation. In a simple yet extraordinary way, she underlined the importance of regular engagement, which is essential to keeping-up relations – especially the ones that are not given, but chosen.

A similar perspective on the subject of social connections can be found in the self portrait of Nicole Baginski. In her drawing I am very hurt, using just ink on paper, she managed to convey the entire spectrum of often contradictory emotions that accompany friendship. Modest in its form, for me it was the most moving work in the exhibition. It was one of very few works that could be understood without employing complex theoretical discourse, delivering the message in purely artistic form. By passing abstract reason, it affects us directly and intensely. Baginski’s piece is full of emotions – anger, sadness, affection, irritation, confusion, longing, helplessness – which flooded her after her dear colleague, who suffers from dementia, misunderstood her intentions and rejected her loving gesture of help.

Teenage utopia

One other piece which I found inspiring was the film The Undercurrent by Rory Pilgrim. This poetic documentary shows a group of teenage climate activists who have separated from their parents to live together in a shared house. The urgency of the matter for which they fight seems to be irrelevant in comparison to the level of negative attention that they receive. Their extraordinary way of living – outside typical family households and openly against the political regime, which they hold responsible for the climate disaster – together with their youth, puts them on the fringe of their conservative community in the state of Idaho (USA), with no legal standing and no choice but to bare with disregarding and often discriminatory adults. Listening to the incredibly mature reflections of the young people pictured in this piece, it is hard to resist thinking that this almost invisible undercurrent is, or at least could be, the real leading force instead of reactionary authorities and institutions. This work seemed most relevant to the central theme of the exhibition; not only does it indicate alternative ways of forming kin, but also presents the reasons for which a kind of societal reorganization, manifesting itself through collective dwelling and creating bonds with those sharing common ideals and sense of justice, might be beneficial, or even – considering the ecological and economic factors such as energy use or food waste of a single-family household – necessary.

Searching for an alternative

While it is hardly a novel idea, as various forms of collectivity have existed in the past and now prevail amongst many non-WEIRD[1] societies, extended kinships are still an exception in our systems, whose laws, codes, and traditions are designed to acknowledge certain social structures and diminish others. The institution of the nuclear family, as described by the functionalist theory popular in the 50s which emerged from the 18th and 19th century bourgeoisie, continues to be regarded as the essential means of socialization, stabilization and guarantor of emotional security that allegedly cannot be achieved outside of marital relationships. If we see it as a political entity, this same nuclear family model performs ideological functions for capitalist society: perpetuating consumption, reproducing class inequality, strengthening power positions, and monetizing emotions. It affects the labor of care, dictates codes of gender and sexuality, and normalizes racially-motivated violations of human rights, like eugenic practices such as the forced sterilization of Black women and women with disabilities in the late 20th century[2]. All the above perspectives – Marxist, feminist and queer – are present within the exhibition and in the accompanying texts. Rather than a critique of family relations, it is an invitation to explore possibilities of different ways of living and creating kin.

Process instead of a product

The exhibition seems to be just one, and maybe not even the most important, part of the whole project. It is necessary to mention the activities accompanying the show and those which led to its realisation. If we look at the display or design concept of the exhibition – usually a task for a curator – we will quickly notice how exceptional the process of exhibition-making was in the case of Unruly Kinships. At that stage, the subject became itself a practice. The show was conceived collectively, the result of a series of meetings of the study group Forms of Kinship. The key idea was explored for over a year not only by exhibition curators, Kris Dittel and Aneta Rostkowska, but also by invited guests and the participants of each meeting. The seminars and workshops covered such topics as family abolition in decolonial perspectives (Sophie Lewis), social and economic history of the family (Mi You), material kinship (Clementine Edwards), nuclear family in relation to capital (Joannie Baumgärtner), radical dreaming (Georgy Mamedov), ancestral spirits (Khanyisile Mbongwa and Li’Tsoanelo Zwane), polysexual economy (Bini Adamczak), neuroqueer intimacy (Francisco Trento) and diverse, feminist modalities of parenting (Karina Kottová and Barbora Ciprová). A collective and extended research phase is not a common way of working in art institutions, whose methods of operating usually resemble production houses rather than process-oriented hubs.

Apart from the fifteen artworks gathered in the gallery space, some of which were solely recordings or documentation of performances, a significant role was placed on the public programme: lectures, workshops, games, listening sessions, concerts, gatherings with food and music or readings. One worth mentioning is Liquid Dependencies, a role-playing game by Liquid Dependencies Theory (Yin Aiwen, Yiren Zhao and Zoe Zhao) and Elli Kuruş. By inviting the public to participate in a simulation, the artists created a possibility to try out unusual ways of creating social relations.

Laboratory

It is not only about choosing to live differently, but being able to have this choice to begin with. Unruly Kinships speaks about kin in context. At the most basic level it reminds us that our needs can and will vary. Such a thought can be comforting both for the ones who wish to take on the nuclear family model and for some reason – be it economic or biological – are unable to, and for others, like LGTBQ+ persons not accepted by their families because of their gender or sexual identity, who are forced to seek affinities elsewhere. The exhibition, public programme, and theoretical texts gathered in the brochure touch upon the complexity of kin-making in many different ways. They intertwine and complement each other, and it is necessary to consider as a whole in order to fully appreciate the scope of this project. While the accompanying text can be read in isolation from the exhibition, the exhibition itself does not hold the same power outside the frame provided by the public program and the narratives built around it.

Most of the displayed pieces are engaging, however looking at some I had an impression that their presence in the gallery was random, lacking a clear logic connecting them with a particular topic or the other works. For an institution that wants to implement the ideas it undertakes, more important than any shortcomings in the presentation of works on display are all the activities going on around them. Namely, successfully playing the role of an open and inviting platform to try out its proposed models of operation, be it cohousing, revolutionary mothering, flighting institutional structures to abolish racial or gender-based privileges, or any other way of queering relations in order to broaden freedom. Unruly Kinships encourages unlearning and inspires unthinkable possibilities to be worked out, together.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski

[1] Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic

[2] Alexis, Pauline Gumbs, m/othering ourselves: a Black queer feminist genealogy for radical mothering, 2023, [in:] Unruly Kinships exhibition folder, p. 16-18.

Imprint

| Artist | Yin Aiwen, Nicole Baginski, Clementine Edwards, Robert Gabris, iSaAc Espinoza Hidrobo & Joanna Stange, Pauline Curnier Jardin & the Feel Good Cooperative, Krõõt Juurak & Alex Bailey, Sethembile Msezane, Rosalind Nashashibi, Lena Anouk Philipp, Rory Pilgrim, Liz Rosenfeld, Selma Selman, Jay Tan, Geo Wyex, and others |

| Exhibition | UNRULY KINSHIPS |

| Place / venue | Temporary Gallery |

| Dates | 4 February – 30 April 2023 |

| Curated by | Kris Dittel, Aneta Rostkowska |

| Photos | Simon Vogel |

| Index | Aneta Rostkowska Clementine Edwards Geo Wyex iSaAc Espinoza Hidrobo & Joanna Stange Jay Tan Joanna Glinkowska Kris Dittel Krõõt Juurak & Alex Bailey Lena Anouk Philipp Liz Rosenfeld Nicole Baginski Pauline Curnier Jardin & the Feel Good Cooperative Robert Gabris Rory Pilgrim Rosalind Nashashibi Selma Selman Sethembile Msezane Simon Vogel Temporary Gallery Yin Aiwen |