In search of impact (yet again). Postartistic practices in the twenty-first century Poland

Impact is a magical word, a fetish, the coveted Holy Grail of the art community.1 Lately, the consequences (or lack thereof) of artistic activities, the need to step outside the safe cocoon of institutions and the seemingly tangible effects of socially-oriented, politically-conscious acts done in the name of art have sparked a fierce discussion in Poland.

These notions have been analysed extensively as evidenced by numerous published works, for example, the widely-discussed Sztuki społecznie stosowane (Applied Social Arts) by Artur Żmijewski2, Muzeum krytyczne (Critical Museum) by Piotr Piotrowski3 and the 600-page long volume Skuteczność sztuki (Effectiveness of Art), edited by Tomasz Załuski4 or the translation of the popular – at least among younger artists – Toward a Lexicon of Usership by Stephen Wright.5 The question about the impact of art became even more pressing after the conservative Law and Justice Party won the parliamentary election in 2015 as cultural institutions started holding politicians to account while a large portion of the art community became ostentatiously indifferent and market-oriented. What impact are we actually talking about? How to recognise or measure it? Who benefits from these “socially sensitive” programmes of public theatres, museums and concert halls?

Kaja Kusztra, a design of a flag for the Consortium for Postartistic Practices for the march ‘For our freedom and yours’, 2019

These are turbulent times in Poland for cultural institutions and their employees, and thus there is a strong desire to incite change. That is why any (dubious) attempt at stepping outside the high culture bubble is celebrated. Illustrative examples of this idea include the fervently analysed action that took place in 2017 when Polish nationalists, supported by Catholic priests, blocked the entrance to the Powszechny Theatre while it staged a play titled Klątwa (The Curse), directed by Oliver Frlij; a new surge of perverse interest in Artur Żmijewski’s short film Berek (The Game of Tag) from 1999, which has been fuelled by Russian trolls; the recent tremendous box office success of the film Kler (Clergy), directed by Wojciech Smarzowski, (some went as far as to interpret the film as an invitation to anti-Catholic rebellion).

Mateusz Kowalczyk ‘Polish shaman’ photo. Wojciech Radwański, 2018

At the same time, a new generation of Polish artists, who stayed somewhat below the radar of cultural institutions, have recently made themselves known. Provoked by measures taken by politicians in power, who pose a threat to the rights of women and sexual minorities as well as the environment, they started using artistic tools outside the traditional system of producing and distributing art. To give this a historical context and find theoretical points of reference, it seems appropriate to point, for example, to the writings of Jerzy Ludwiński from the early 1970s.6 Ludwiński (1930-2000), who was a theorist, lecturer and art critic, used the term “postartistic age”, which seems to be the key notion for understanding certain changes occurring in contemporary art.7 He pointed to the fact that art and other disciplines are intertwined. Further, he postulated that the new art is impossible to define and put in the frames of institutional apparatus we have at our disposal. “It is very possible that we no longer deal with art. We missed the moment when it transformed into something totally different, something we do not know how to call any more. However, we can be sure that what we engage in nowadays has greater potential”.8 This greater potential he refers to essentially translates to the ability for artists to work outside the world of art, in the realm of political protest, ecology, LGBTQ activism, alternative tourism, natural sciences, etc.

By updating Ludwiński’s proposition and relating it to specific approaches adopted by artists making art in the twenty-first century, I would define postart as:

A long-term artistic practice that does not lead (or only occasionally so) to the creation of a material work of art capable of a clear-cut allocation of authorship and also inaccessible to the viewer by the means of the conventional apparatus of distribution: the work of art – workshop – exhibition – museum. Usually such practices are characterised by the employment of competencies from beyond the realm of art, incorporating various, also para-artistic subjects and also by going through phases of dormancy and increased activity. Post-art is most often devoid of features (or they remain hidden) that enable us to identify the activities that it comprises or objects from the non-artistic backdrop (title, author, originality, exhibition architecture, durability, etcetera). At the same time, post-art can be part of other para-artistic systems such as economics, political activism or horticulture.

Several artists working collectively and individually in Poland subscribe to this understanding of postartistic practices as a bond that holds together various areas of knowledge and professional expertise; they do not have clear authorship and cannot be easily “captured” by institutions. An initiative undertaken by a group of women calling themselves Polish Mothers on Tree Stumps can serve as an example. The campaign, founded by a visual artist Cecylia Malik, was launched as a response to the large-scale logging that took place in 2017 – a result of the so-called Lex Szyszko. Malik posted a photo of herself sitting on a tree stump breastfeeding her son Ignacy (taken in Krakow). Soon after, other mothers joined posing in group photos. The group members demanded that the law on cutting down trees by private landowners be amended and that the Minister of Environment Jan Szyszko be deposed. In the Vatican, the mothers handed Pope Francis one of the photographs along with a report detailing the environmental damage done in Poland, citing his encyclical Laudato Si. The photograph of Polish Mothers circulated in the media: it even appeared in The Guardian in an article about Polish environmental policy.9

Anna Siekierska in a sow costume for Forum for the Future of Culture, courtesy of the artist, 2018

The Polish translation of the previously mentioned Toward a Lexicon of Usership10, by a Canadian theorist Stephen Wright, turned out to be an essential element driving the conversation about social and political consequences of artistic activities in recent years. The notions proposed by Wright can be a reference point as well as the key to interpreting activities of such artists as Jana Shostak, Katka Blajchert, Katarzyna Kalinowska, Alicja Wysocka or the members of the Consortium for Postartistic Practices. In the book, Wright states that the roles currently played by producers and consumers of culture need to be redefined. He encourages readers to rethink the (passive) role of a spectator, (the hegemony of) an event and object; he challenges Kant’s “purposiveness without a purpose”, the need to replicate existing systems, the regime of ownership and authorship and high-mindedness of the so-called expert culture. Wright is a propagator of artistic practices on the 1:1 scale, using “the world as its own map”. Artists operating on the 1:1 scale cultivate the land, open antique shops and their own museums, work in hospitals and the local government, they are therapists and shamans, they come up with solutions to economic problems, etc.

Consortium for Postartistic Practices, ‘Justice is a mainstay’

reconstruction of an actoin of the Academy of Movement, photo. Sebastian Cichocki

Nevertheless, it is hard for institutions as well as spectators to recognise art on the 1:1 scale because their “defining features”, which allow such practices to be captured, named and aesthetically evaluated, are deconstructed (Wright calls them conceptual edifices, e.g., the objecthood of a piece of art). A project by Jan Szewczyk and Tomasz Koszewnik, Wracając do Białowieży (Returning to Białowieża, initiated in 2015), is an example of a practice on the 1:1 scale. This hard to define artistic programme was part nature escapade, open university, an open-air artistic event, an autodidactic group and sociological participant observation. The two artists proposed holding an event for students of the Postgraduate Studies Programme (at the University of Arts in Poznań) in the Białowieża Forest, organised in cooperation with the Jan Józef Lipski Open Univeristy of Teremiski. Aside from bicycle trips, there were meetings with local experts from different fields: naturalists, artists, biologists, historians, etc. The project of Jan Szewczyk and Tomasz Koszewnik was problematic in the sense that transferring (post)artistic practices to institutions is complicated; in the traditional media such transfers occur between a workshop and an exhibition hall.

Another term that describes a great deal of contemporary artistic practices in Poland is “occupational realism”. It was coined by Julia Bryan-Wilson11, who took advantage of the fact that the word “occupational” in English can relate either to employment or military occupation of a country. According to Bryan-Wilson, “occupation realism” is the practice “in which the realm of waged labour (undertaken to sustain oneself economically) and the realm of art (pursued, presumably, for reasons that might include financial gain, but that also exceed financialisation and have aesthetic, personal and/or political motivations) collapse, becoming indistinct or intentionally inverted.”12

Katka Blajchert, photo. Ernest Wińczyk, 2014

In Poland, art projects that follow the principles of “occupational realism” were conceived mostly by women: Julita Wójcik, Joanna Rajkowska (e.g., Dwadzieścia dwa zlecenia – Twenty Two Tasks, 2003-2005); Paulina Ołowska (Nova Popularna, with Lucy McKenzie, 2003); or Elżbieta Jabłońska (Przez żołądek do serca – Through the Stomach to the Heart, since 1999, or Nieużytki sztuki – Art Wastelands, since 2014). Julita Wójcik, in particular, has enacted many tasks which turned physical work into artistic performance. The artist herded goats (Rewitalizacja Parku Schopenhauera – Revitalise the Schopenhauer Park, 2002) and swept the floor in a factory (Pozamiatać po włókniarkach – To Sweep Up After Textile Workers, 2003). Currently, an artist whose artistic programme borrows from “occupational realism” is Katka Blajchert, a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk. She runs a highly regarded hairdressing salon, Ciach (Snip), and has gained a reputation as a hair care expert, offering beauty tips in hair care magazines. However, Blajchert is not straightforward about what this undertaking really is, never clearly defining it. On the one hand, she is in the hairdressing business, on the other, there is evidence that this activity can be interpreted as an artistic performance exemplified by the fact that she submitted her salon to a competition for young artists – Hestia Artistic Journey (her showpiece consisted solely of a pile of the salon’s business cards on a chair13).

Agnieszka Polska, a project of a Christmas card for the Consortium for Postartistic Practices, 2017

The common denominator of these diverse (post)artistic practices of a younger generation of artists is using artistic tools and competences outside the art world. It often leads to “displacements”: centre-outskirts, city-countryside, autonomous art-useful art (Arte Útil). Nowadays, practices of such sort, often stretched in time and essentially not included in the programmes and collections of art institutions, are abundant; the following serve as examples. Jaśmina Wójcik – an activist and visual artist – uses drawing, sound, film and performance in order to change the way we perceive reality and self-organisation. Her project entailed working with former employees of the defunct Ursus Factory which manufactured tractors during the Polish People’s Republic (PRL) period. The outcome of this project is a feature film Symfonia Fabryki Ursus (Symphony of the Ursus Factory, 2018), which includes an experimental piece of music performed by the former workers, based on the sound of tractors. Agnieszka Pajączkowska – a theorist and artist – treats photography as a tool of social engagement, combining scholarly reflection with creative practice. She travels around Poland operating a Mobile Photography Studio and provides photography services to town and country dwellers. Natalia Romik – an artist and curator – considers exhibitions as a means to fight for the truth and historical memory. She creates elaborate programmes focused on the Jewish legacy in Poland and initiated the Nomadic Shtetl Archive – a mobile museum and research centre that will travel along the south-eastern regions of the country. Szalona Galeria (the Wild Gallery), launched by Janek Simon, Agnieszka Polska and Kuba de Barbaro, operated along similar lines; it was a nomadic contemporary art gallery that brought avant-garde art, performance and contemporary painting to small towns and villages. Daniel Rycharski, a visual artist working in a small village, Kurówko, uses art as an instrument of mobilisation, cooperation as well as provocation, touching upon subjects like faith, stigmatisation of sexual minorities or historical memory. Rycharski initiated several projects for his neighbours, in which they actively participated, e.g., Wiejski street art (Rural Street Art). In 2009, after graduating from university, the artist returned to his home village, Kurówko. He was inspired by the tales of fantastical creatures that inhabit the nearby forest and painted a mural of a hybrid animal on one of the houses. Before long, having such a mural became a point of pride for local households. Kurówko is probably the only village in Poland whose head also introduces himself as a curator. Rycharski, together with people from his rural community, created Ogród zimowy w Kurówku 2013 (Winter garden in Kurówko), a kind of graveyard for scrap metal from tools and agricultural machinery that was transformed into flower sculptures. Plenty of postartistic practices that leave city limits focus on ecological issues and interspecies relations, taking tools and competences from the realm of visual art and applying them in green activism. Anna Siekierska’s activity is a case in point. She is a sculptor who, with the aid of art, speaks on behalf of other species that are exploited and discriminated against by people; she fights for the environment, the well-being of animals and plants. Her activities include cataloguing hunting platforms and building hen houses for “retired” birds.

Daniel Rycharski ‘Fears’ Kurówko, photo. Daniel Chrobak, 2018

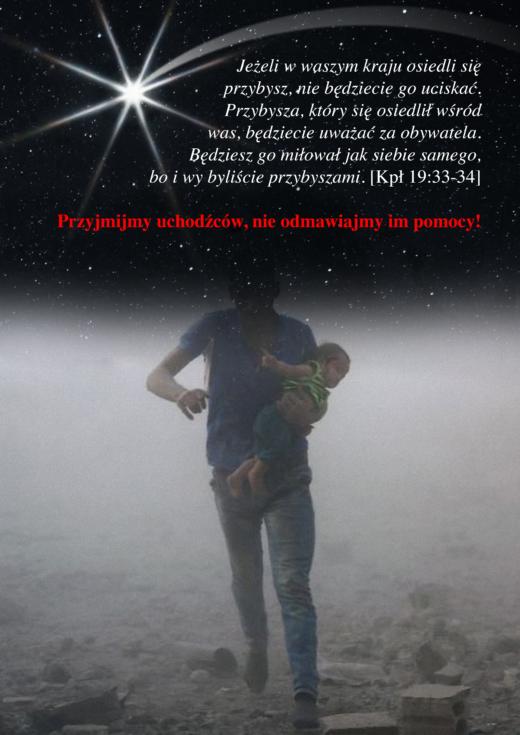

One question has become important for many contemporary artists and art institutions, namely, how to delineate the limits of art in view of such subjective experiences as gathering in a forest, protesting in front of the Sejm (the lower chamber of Polish Parliament) or running a food co-operative? Increasingly, art has permeated other, completely non-artistic systems, such as ecology, politics, agriculture, religion, anthropology or therapy. It constitutes a distinct sphere of human activity whose cross-disciplinary character and blurred boundaries contribute to its vitality and ability to adapt. These blurred boundaries enable art to conquer new lands which lie “outside the realm of art”. Thus, the need to separate artistic activity from professional activity, pieces of art from objects of daily use or artistic competences from social ones has become not so much irrelevant as, and more importantly, secondary in today’s institutionalised world of art (which is even more evident outside institutions). Regarding artistic practices on the 1:1 scale, which usually take form of elaborate and long-term programmes launched by artists, showing them in a gallery should not lead to their being “captured” by institutions. They should serve the purpose of distributing information, emphasising particular competences used by artists (interdisciplinary thinking, unorthodox way of manufacturing knowledge, erecting temporary institutions, etc.) as well as encourage people to venture on one’s own into the world that exists outside museums. The artistic practice of Jana Shostak is an excellent example of this type of “migration” outside the art bubble, supported by contemporary art institutions. She consistently uses art as a tool to hack14 other non-artistic systems, such as the Polish language, beauty pageants or religious pilgrimages. Shostak launched a campaign to change the Polish word “uchodźca” (meaning ‘a refugee’) which, in her opinion, is burdened with prejudice and stigma. Her suggestion is to replace it with the word “nowak” (which shares a root with the Polish word ‘nowy’ meaning ‘new’ and can be loosely translated as ‘a newcomer’) is a homonym of one of the most common Polish surnames, which is neutral in connotation and constitutes a humorous word-play. The artist decided to take advantage of the considerable press, radio and TV coverage (including her appearance in the programme Słownik polsko-polski – Polish-Polish Dictionary – hosted by a celebrity professor Jan Miodek and broadcast by public television) as well as her campaign’s popularity in social media to attempt and step outside the autonomous realm of art that does not have a huge impact on the world. Shostak prefers to describe herself as an initiator of a process rather than an author of “a piece of art”. More recently, she has been participating in beauty pageants in an attempt to permeate the organisational structure of the Miss Polonia pageant and make slight modifications, like advocating the use of feminine nouns by the contestants.15

Consortium for Postartistic Practices, rehearsals for the march ‘For our freedom and yours’ photo. Monika Bryk, 2019

The practice of the Consortium for Postartistic Practices (KPP): a broad but informal collective of art workers established during the 2016 Culture Congress in Warsaw also brings together diverse experiences from the world of art and non-art. The majority of activities that are agreed upon during the group’s meetings is anonymous and connected with women’s rights, ecology and anti-fascism. It is clear that the collective makes reference to the writings of Jerzy Ludwiński and the conditions of making art in the “postartistic age”. The goal of the Consortium’s activity (whose members took part in the protests defending the judiciary independence in Poland in 2017 and 2018) is mobilising people, exchanging ideas, distributing information and, most of all, opening “channels” which allow art and other spheres of social life to merge. KPP often uses historical reconstruction; for example, in 2017, they recreated a political action of the theatre group, Akademia Ruchu (Academy of Movement), titled Sprawiedliwość jest ostoją (Justice is a Beacon) from 1980. The symbol and a mascot of the group is a duck-rabbit, an optical illusion which appears, for instance, in psychological tests created by Joseph Jastrow and in Philosophical Investigations by Ludwig Wittgenstein. The image conveys the subversive and ambiguous nature of many contemporary artistic attitudes and practices in Poland, which are both art and non-art, many things at once, something that eludes musealisation and resists being captured by the language of art criticism and the art marketplace.

This text first appeared in the book On the Edge edited by Kateryna Botanova and Wojciech Przybylski, published in the series Culturscapes.

Translated by Monika Ajewska.

1 The text is part of a broader debate (conversations, articles, etc.) regarding “postart” and “art on the 1:1 scale” that took place in connection with the exhibition Making Use: Life in Postartistic Times, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2015, curators: Sebastian Cichocki and Kuba Szreder in collaboration with Stephen Wright as well as the 2017 and 2018 editions of Forum for the Future of Culture organised by the Powszechny Theatre.

2 Artur Żmijewski, ‘Stosowane sztuki społeczne’, Krytyka Polityczna, 2017, 11/12.

3 Piotr Piotrowski, Muzeum krytyczne. Poznań: Dom Wydawniczy Rebis, 2011.

4 Skuteczność sztuki, edited by Tomasz Załuski. Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, 2014.

5 Stephen Wright, W stronę leksykonu użytkowania. Warszawa: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, 2014.

6 Popularised in recent years by the Wrocław Contemporary Museum, which holds a permanent exhibition dedicated to Ludwiński (‘Jerzy Ludwiński Archive in Wrocław Contemporary Museum is a permanent exposition-research space, which combines elements of an exhibition, archive and art warehouse.’, http://muzeumwspolczesne.pl/mww/wystawy/archiwum-jerzego-ludwinskiego-2/, accessed 10 December 2018), or through the exhibition Making Use: Life in Postartistic Times, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2015.

7 Jerzy Ludwiński, ‘Sztuka w epoce postartystycznej’, Sztuka w epoce postartystycznej i inne teksty, edited by J. Kozłowski. Poznań: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Poznaniu, 2009, 57.

8 Ibid., 66.

9 Christian Davis, ‘Polish law change unleashes “massacre” of trees’, The Guardian, April 7, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/apr/07/polish-law-change-unleashes-massacre-of-trees, accessed 10 December 2018.

10 The book by Stephen Wright was originally published by Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven on the occasion of the Dutch edition of Arte Útil, a long-term programme implemented by a Cuban artist and activist, Tania Bruguera. The Lexicon is a set of language tools, specifying goals as well as challenges that artists and cultural institutions of the twenty-first century have to face.

11 Julia Bryan Wilson, ‘Occupational Realism’, It’s the Political Economy, Stupid!, edited by G. Sholette, O. Ressler. London: Pluto Press, 2013.

12 http://arthistory.berkeley.edu/pdfs/faculty%20publications/Bryan-Wilson/jbwoccupationalrealism.pdf, accessed 12 December 2018.

13 The finalist exhibition of the sixteenth edition of the Hestia Artistic Journey, 27 June – 9 July 2017, Museum on the Vistula, 22 Wybrzeże Kościuszkowskie, Warsaw.

14 Stephen Wright, W stronę leksykonu użytkowania. Warszawa: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, 2014, 65.

15 Piotr Policht, ‘Bez śmiechu nie ma rewolucji. Rozmowa z Janą Shostak’, Szum, July 6, 2018, https://magazynszum.pl/bez-smiechu-nie-ma-rewolucji-rozmowa-z-jana-shostak/, accessed 12 December 2018.