The circle of young Kharkiv photographers, which has been later described by researchers as the Kharkiv School of Photography, was developed in the 1970s in Soviet Kharkiv. The activities of this circle were aimed at creating a visual opposition to the dominant Soviet narratives and the aesthetic canon of Socialist Realism. It can be said that the Kharkiv School of Photography is an anti-Soviet protest formulated in the language of photographic imagery. The works by the School’s founders and participants (Boris Mikhailov, Jury Rupin, Oleg Maliovany, Evgeniy Pavlov, etc.) were censored by the authorities, their exhibitions were closed, and their workshops were searched. And yet, despite all the obstacles and restrictions, the Kharkiv School of Photography quickly formed into a powerful photographic movement with a recognizable visual style and characteristic means of expression. These include experiments with form, the use of photographic techniques, photomontage, film and photograph coloring, diapositive layering, strong retouching, combining photographs with texts, and more.

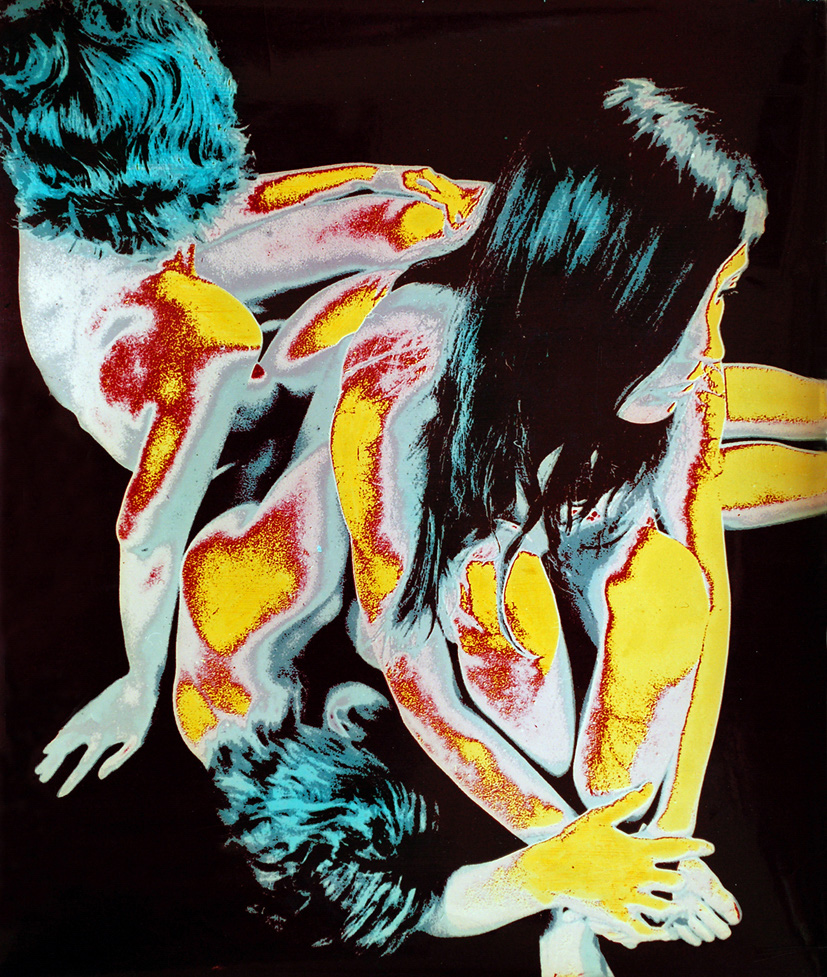

What exactly was the protest of the Kharkiv School of Photography? Socialist Realism glorified the asexual athletic body, the joy of selfless work, and creates an ideal picture of the standardized life of a Soviet man who is completely devoid of individuality. In contrast to this utopian aesthetics, the representatives of the Kharkiv School photographed the areas of suppression: something that was ignored or tabooed by the official narrative. Food queues, homeless people, alcoholics, prostitutes, and eroticized (or distorted) naked bodies got caught in their lens [1]. They often turned to kitsch, carnival and anti-aesthetics in their works. Whilst there was ‘no sex’ in the Soviet Union, the Kharkiv School created the erotic images on the verge of pornography. Whilst World War II was perceived exclusively in terms of the heroic feat of the Soviet people who defeated Nazism, the Kharkiv School turned everything into a carnival with dressing up. Whilst the Holodomor, an artificial famine of 1932-1933 that claimed up to 4 million lives, was total taboo in the Soviet Union, the Kharkiv School was trying to fill the gap of missing images with photographic phantoms.

Oleg Maliovany, ‘The Nude Trio’, 1972, courtesy VASA Project / the Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography

In the Soviet Union, it was never safe to undermine its official narratives. The repressive state apparatus used special care to thwart such efforts and punish the perpetrators. The Holodomor, despite the horrifying scale of the crime, was a blank page in the Soviet history, an event that did not officially occur. It was forbidden to photograph the starving people. In one of the numerous cases of the Great Purge of 1937, in the transcript of the interrogation we find the following dialogue between an NKVD officer and a detainee: “Did you take pictures of the beggars?” “Yes, I took a picture of a beggar to have a document that testifies to a difficult life in 1933.”[2] Although this attempt to capture the horrors of the Holodomor was not the main reason for the arrest, the accused was sentenced to death and the photo was destroyed. The regime was not just destroying people, it was trying to erase the very memory of them and their destiny.

Instead of erased evidence of crimes, Soviet propaganda created an idealized picture of the flourishing Ukrainian village. A striking example of the contrast between the official representation and the terrible reality is the painting Picking Tomatoes and the tragic fate of its creator.

In 1932, at the height of the Holodomor, Ivan Padalka, a student of Mykhailo Boichuk, painted a canvas with plump women gathering harvest in an area full of vegetables. But the readiness to follow the ‘party line’ did not protect the Ukrainian artist: in July 1937, he was executed on trumped-up charges of terrorist activity. The tradition of suppressing the Holodomor lasted almost as long as the Soviet empire. Boris Mikhailov, the founder of the Kharkiv School of Photography, comments on the lack of documentary evidence: “In the history of photography in our country, we have no photographs of the famine of the 1930s in Ukraine, when several million people died and corpses lay in the streets. We do not have photographs of the war, because journalists were forbidden to show the pictures of grief that threatened the morale of the Soviet people; we have no ‘unpolished’ photos of enterprises, no images of street events, except for demonstrations. The whole history of photography is ‘covered with dust’.[3]

Ivan Padalka, ‘Picking Tomatoes’, 1932, National Art Museum of Ukraine, the work is in the public domain

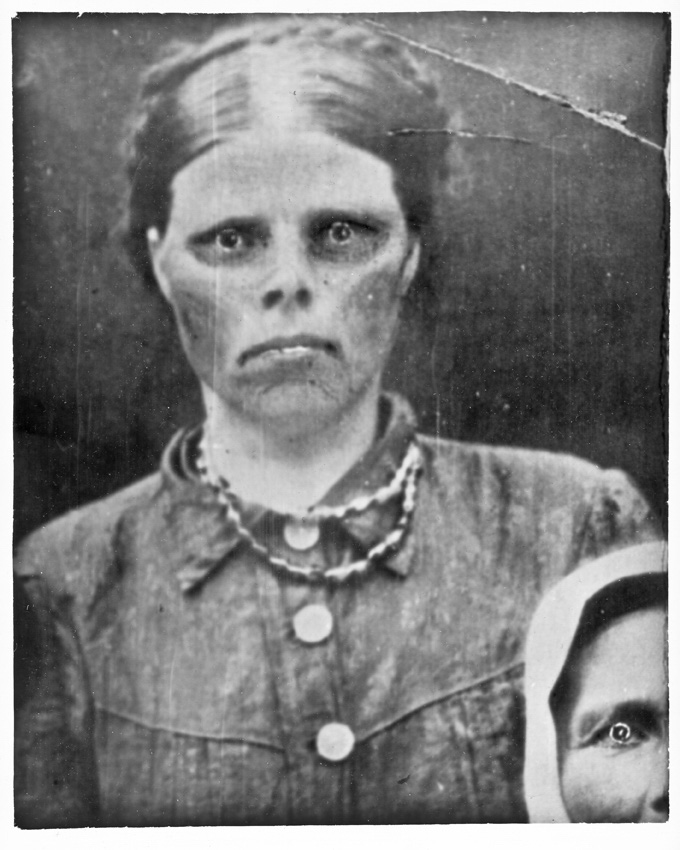

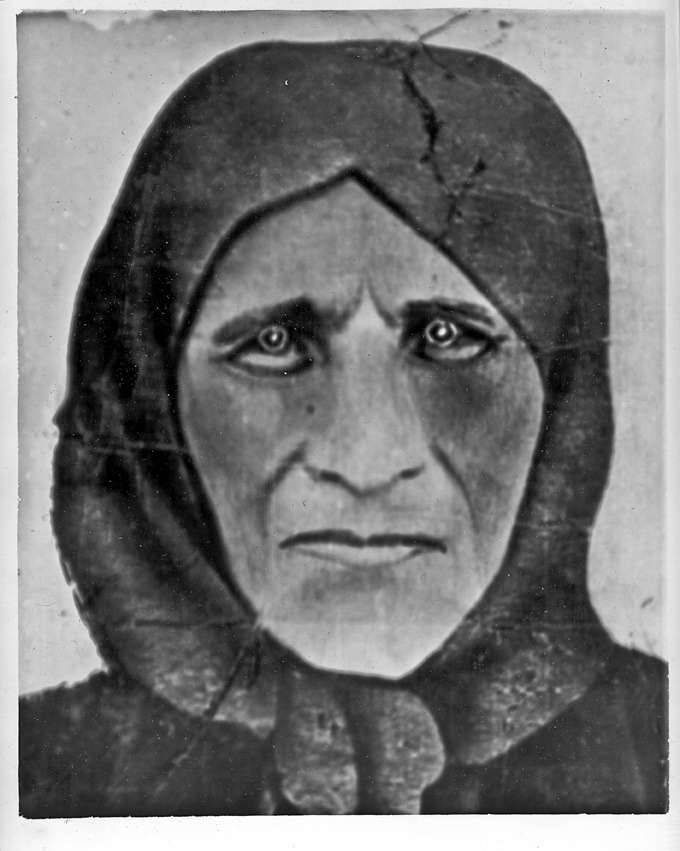

Roman Pyatkovka, a representative of the second generation of the Kharkiv School of Photography, learned about the Holodomor from the samvydav (self-published underground leaflets). Impressed by the scale of the catastrophe and disturbed by the cynicism of its suppression, the artist starts creating a dramatic pantheon of ghosts, which are not so much a representation of a particular man’s fate as a type, archetype, ghost drawn from the depths of the collective memory. This is how the series Phantoms of the 1930s. Holodomor was created in 1988.

“This series is the portraits of those who were victimized by Stalin’s repressions and the Holodomor of 1932-1933. Some faces are the paraphrases of typical portraits in the heroic style, which distinguished the totalitarian period full of ‘honours boards’; some resemble yellowed photos from the family photoarchives of the village inhabitants, which were arranged in the form of an iconostasis. Each portrait has its own story: an executed priest, a head of the state farm, a milkmaid, a Komsomol leader, a commissar killed by hungry rural men, and a cannibal woman who killed her mother. The documentary basis of these photographs is obvious. However, this project is not a series of documentaries. It is an artistic imitation of a number of real facts that lead the viewer to the realm of myth”, says the artist about his project.[4]

In Phantoms, we will not see the faces of real victims: when in a situation where it’s impossible to turn to the archives and documentary sources, the artist is forced to follow his own idea of the tragedy and the information he received from the samvydav. The absence of official sources and images leads to the fact that the real historical tragedy is thought and depicted in the categories of myth, becomes the incomprehensible evil that is not subject to the categories of rational analysis. The destruction of the evidence of the Holodomor and the suppression of the stories of its victims create a world without words and images, a space of the horror that resists both language and image. Thus, the opposition to oblivion, the attempt to give shape to the unthinkable, also occurs through imaginary categories and generalized images. We can’t name a priest, a milkmaid or a head of the state farm who look at us from densely retouched portraits. Though it happens not only because of the lack of documentary evidence, but also because we guess that there were incomprehensibly many such stories, that behind each face in the series a chorus of voices and stacks of tragic biographies hide.

The opposite example of Soviet propaganda is the official heroic narrative of the Great Patriotic War, for which World War II began in June 1941. Therefore, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the role of the USSR as Hitler’s temporary ally in the attack on Poland were excluded from it. There was no room here for the Holocaust as well, which was labeled as a ‘crime against the peaceful Soviet citizens’ without specifying the ethnicity of the victims. There was no room for civilians’ sufferings, war invalids, and mass rapes. There was no room for the post-war waves of famine and the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe. All that remained was the history of the heroic struggle of the Soviet people against the enemy, where the figure of a Soviet soldier represented a hero struggling with absolute evil and saving the world from the ‘fascist invasion’ (a term with which the Soviet ideology replaced Nazism).

The reaction of the Kharkiv School of Photography to obsessive propaganda of victory was in the same form as their reaction to other manifestations of the official imposition of the state’s position. In the project If I Were a German, the Fast Reaction Group (which included Boris Mikhailov, Sergey Bratkov and Sergiy Solonsky) along with Vita Mikhailov traditionally refer to the burlesque and dressing up in order to turn upside down the ‘dubious policy of looking at history through the eyes of the winner’ by means of carnival[5].

In the series of staged black-and-white photographs, we see the protagonist’s carefree pastime outdoors and indoors, surrounded by dogs, cats, and naked women. In terms of mood, these photographs are almost indistinguishable from the old works by these and other representatives of the Kharkiv School of Photography (the same goes for Evgeniy Pavlov), with one difference. The protagonist of the series is dressed in the uniform of SS-man, and this conscious provocation completely changes the images’ register. It seems that the artists are trying to tell us that were they ‘Germans’ (or rather members of the units recognized in Nuremberg as responsible for mass crimes), they would live the same life they live now, only they would wear uniforms.

It is important to note that the project was created in 1994, a few years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The empire no longer existed, and in Ukraine the cult of the Soviet victory was no longer the only dominant narrative. The ability of the new Russian government to keep imposing the same narrative on the post-Soviet countries was still at its lowest. The room was cleared to create a new narrative that would be more sincere, inclusive, focused on victims rather than artificial heroes. But all that the Kharkiv photographers, who have been accustomed to being in opposition to the Soviet official canon since the mid-1970s, were able to create in this window of opportunities, was another reproduction of their old protest performances.

But, despite the more or less successful effect of these attempts to fill the gaps of the non-existent photo representation with their own projects, the Kharkiv School of Photography tried to find a language to talk about complex historical events, and new generations of young photographers rely now on their foundations.

The article has been written for the project Kharkiv School of Photography: From the Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics. The project is implemented within the Ukraine Everywhere program of the Ukrainian Institute.

[1] Igor Manko: The Kharkiv School of Fine Art Photography. First published in VASA Journal on Images and Culture, Issue 7,2014. http://www.vasa-project.com/gallery/ukraine-1/igor-paper2.php

[2] Kharkiv region State Archive, P6452, op.1, case #5276

[3] Mikhailov B. Case History. Berlin ; Zurich ; New York : Scalo, 1999. Р. 7.; Nadiia Kovalchuk. No Photo. KORYDOR, October 5, 2020 http://www.korydor.in.ua/ua/stories/piatkovka-holodomor-photo.html

[4] Museum of Kharkiv Photography, Phantoms of the 1930s. Holodomor https://www.moksop.org/art/artprojects/fantomy-30-kh-rokiv-holodomor/

[5] Halyna Hleba, Kateryna Yakovlenko, The Place of the Travesty: Was There a Queer in Kharkiv Photography? October 2, 2020 supportyourart https://supportyourart.com/researchplatform/queer-kharkiv-school

Imprint

| Index | Andrii Dostliev Boris Mikhailov Evgeniy Pavlov Fast Reaction Group Jury Rupin Lia Dostlieva Oleg Maliovany Roman Pyatkovka |