Belarusian curator and contemporary art critic Lena Prents in her text on the landmark exhibition of contemporary Belarusian art “Opening the door? Belarusian art today” held in 2010–2011[1] specifically mentioned Arthur Klinov’s photo project “The Sun City of Dreams” (2004). According to the researcher, “discursive formation of a new semantic context based on different perspectives” failed to develop in regard to it. This happened through no fault of the Belarusian artist himself, but more despite the significance of this project, which was equally welcomed by both the artistic community and the general public in Belarus.[2]

Using Lena Prents’ expression “discursive formation of a new semantic context”, now irrespective of Arthur Klinov’s photo project, I singled it out as a separate, independent strategy for photography recognition in Belarus. This strategy implies not only the topicality of issues and problems raised in photographers’ works, but also the novelty of their technical methods and principles. It is about new ideas and interpretations of reality born at their intersection in the viewers’ minds, which makes it possible for us to arrive at conclusions about the changes in social, political, cultural conditions of photographers’ work.

So, why is it so important to talk about strategies which enable photography to gain visibility and get recognized in Belarus and abroad? Because some photographs and photo series are more frequently cited and mentioned in albums, research texts or at exhibitions, and it hardly happens by chance – although definitely it also matters.

Turning to strategies of giving significance to certain photographs within and beyond photographic community allows us not only to offer a number of perspectives for their consideration, but also to better see social, political and cultural processes these photographs are associated with. This means, that, on the one hand, we will be able to see both these images and processes in a new way, and on the other – to contribute to their historicization and archiving.

So, it is in order to solve this problem and in a dialogue with curators and researchers Hanna Samarskaya and Antonina Stebur, as well as after conducting my own analysis of visual and textual material on Belarusian photography, I have highlighted a number of strategies for Belarusian photography gaining visibility and recognition; further dividing them into two big parts. The former brings together the strategies where the focus is made mostly on photographers’ principles and methods of work.

Liankevich A., ‘Double heroes’, 2011

Among them there are:

- “Discursive formation of a new semantic context based on different perspectives”,

- “New formal principles”,

- “Photography beyond photography” and

- “The revolution of the image.”[3]

The latter includes strategies centered on the methods of crystallization and changes in the photographic content directly, which I have defined as:

- “The local encountering the global (meanings and contexts)”,

- “Changes in the body’s symbolic function” and

- “New sensitivity.”

The strategies from the second part illustrate the specificity of Belarusian photography, also putting it in a wider context, since they help to discover similar strategies in other countries. At the same time, a number of works and series made by Belarusian photographers will respond to several strategies from both the groups at the same time revealing that different ways of Belarusian photography recognition could also overlap.

“NEW FORMAL PRINCIPLES”

The history of Belarusian photography is gradually becoming the subject of research, primarily outside state educational and research institutions. Thanks to the Internet portals “ZNЯTA” and “Kalektar”, the collection of “pARTisan” almanac albums, the communities formed around the “NOVA” gallery of visual arts, “CECH” art-space and “The Month of Photography in Minsk”, not only can we see Belarusian photography, but also read interviews with photographers and critical reviews of their works written by local experts in the art field. All this allows us to systematize Belarusian photography on various grounds and place it in various semantic contexts that contributes to its better understanding and interpretation.

The most obvious periodization is chronological and it reveals several turning points in the history of Belarusian photography at the second half of the XX century.[4] In Belarus, the 1970s were marked by the development of photo club photography triggered by the establishment of “Minsk” photo club in 1960. It was one of the first photo clubs in the USSR, and in the 1970s photo clubs existed in almost all the regional cities of the BSSR.[5] This photography, according to photo club movement participants, differed from what could be seen in Soviet magazines and newspapers. It showed other photographic opportunities liberating it from the necessity to solve propaganda problems and form a positive worldview. Photo club members were making clear statements about a possibility of photography to be seen as an independent art form, not reducible to any ideological order. In the first half of the 1980s, the amateur photographic movement in the BSSR began to decline. The first steps were made towards the professionalization of art photography around individual figures who began to articulate new requirements to their own community and future followers.

However, another significant turning point occurred in the late 1980s not only due to internal transformations, but also due to changes in political conditions, namely, “perestroika”. In this period, put into international art context, Belarusian photography started getting recognized outside the country. By the mid-1990s, Belarusian photographers had begun to speak about a new sense of time and lack of institutional conditions for the development of contemporary photography in Belarus. In the 2000s and 2010s, these conditions were getting gradually formed – with the advent of new independent gallery spaces, new art associations and educational projects, as well as thanks to new strategies for Belarusian artists’ participation in international exhibitions.

“New formal principles” Belarusian photography recognition strategy I am interested in can be traced at almost every stage mentioned above, and it is associated first with a turn from commissioned photojournalism and photo-documentary shooting to personal photo-documentary and art photography practices (including multimedia) actively interacting with other types of arts. Then, in the 2000s, new principles make themselves felt in conceptual and research photography, also due multimedia roles getting more pronounced and diverse.

One of the Belarusian photographers whose projects were breaking with formal photographic principles more or less shaped in the 1980–90s is, in my opinion, Andrei Liankevich. And as a recognizable work of his, I would like to mention “Double heroes” photograph from the series “Goodbye, Motherland!” (2011). This work does not aim at reaching the tasks articulated by the Belarusian photography of the 1970-90s – namely to propose a system of aesthetic and meaningful coordinates, alternative to the Soviet one, relying primarily on the photographer’s autonomous personal experience. This experience could also be collective, for example, when one was a part of the photo club movement, however, its spokesmen did not aim at going beyond photography as a medium because they were defending their autonomy and originality, not recognized outside photo clubs in Soviet times.

And although some exceptions could be found in this regard – primarily in Galina Moskaleva’s and Igor Savchenko’s photography, the tendency was still dominant. It can also be traced in the opposition of the statement made by photography with the social and political system as totality, which Vladimir Parfenok, for example, speaks of in his commentary on his series “Persona non grata” (1988). This means that if the system is faceless and homogeneous, then the heroes opposing it are unique and inimitable. When making something like his own collection of these unique characters, Parfenok’s project “Persona non grata” reveals the deliberate violation of the formal principles that were then determining Soviet photojournalism.

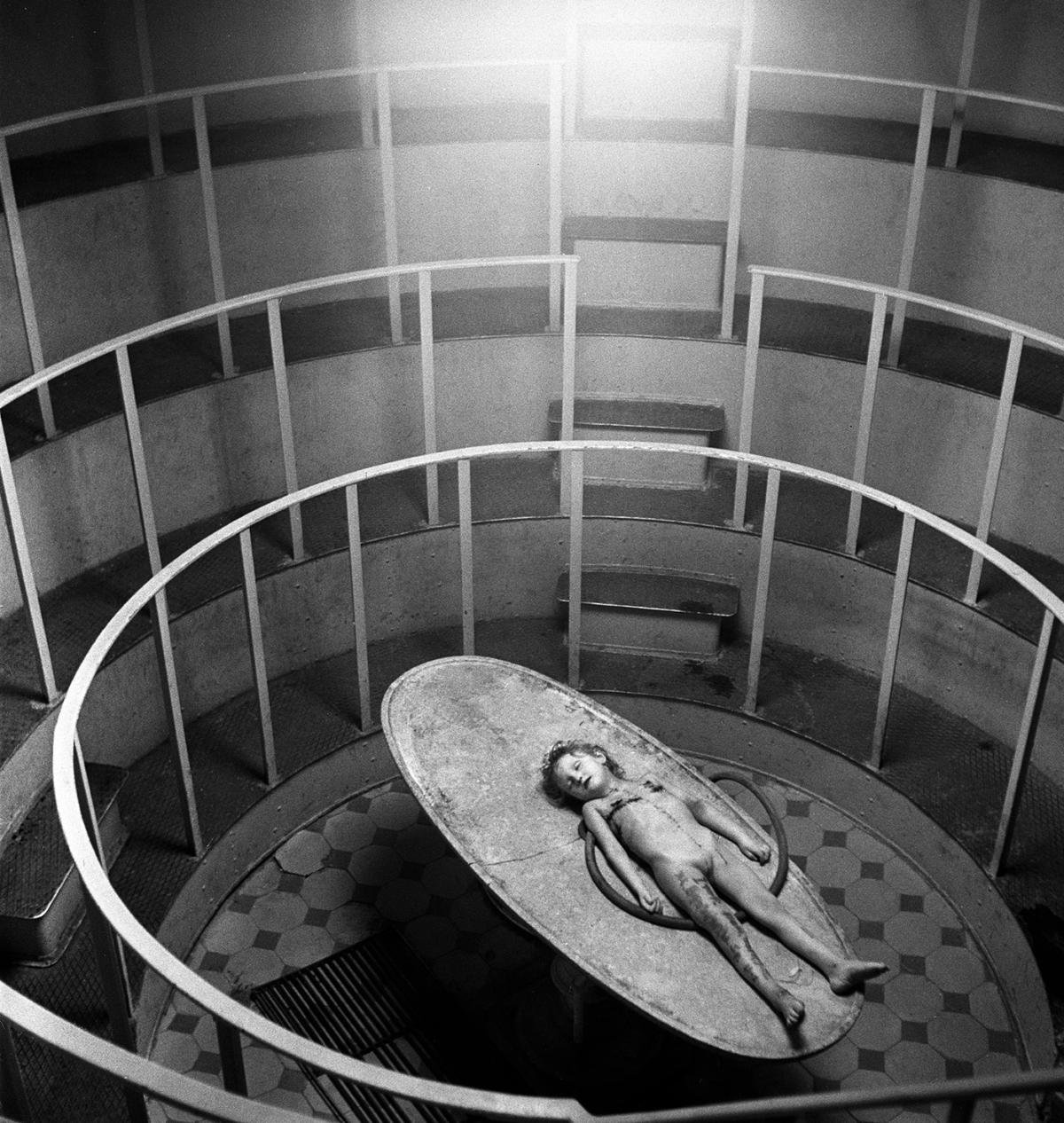

Moskaleva G. and Shakhlevich V. from the series ‘Madhouse’, 1991-1992

Breaking with the “individuality — system” opposition, Andrei Liankevich’s “Double heroes” reveals a new turning point. On the one hand, we see a rejection of the individualizing component at the level of the image, since this portrait can easily be put on a par with others – massively produced according to a certain template, for example, in passport photography. On the other hand, it discloses not only the conditionality, or cultural and historical determinism in constructing any identity that we see in Vladimir Parfenok’s series, but also the aspect of the individuals’ getting erased in the very process of identification, never free from any ideology. One of its consequences is understanding that the formation of individuality, or originality, is also a specific social practice, and not an out- or anti-systemic phenomenon. The “individuality — system” in this case is replaced with a set of social and political conditions that the photographer must make visible in his statement. And to do this, he needs to conduct a study, because these conditions most often are complicated and not transparent. And his authorship and autonomy are subordinated to research goals.[6]

The projects of another Belarusian photographer Siarhei Hudzilin aim at revealing such conditions – in particular, his series “Mi(e)nsk (in Progress)” he has been working on since 2013. The photograph “Silver Man” presented in this series breaks with Vladimir Parfenok’s individualizing approach and Andrei Liankevich unifying strategy: here we can discern something like a link between both. We witness a living person gradually transforming into a social function and the urban space as his background. A possible research of the latter could help us clarify the specificity of this transformation.

“PHOTOGRAPHY BEYOND PHOTOGRAPHY”

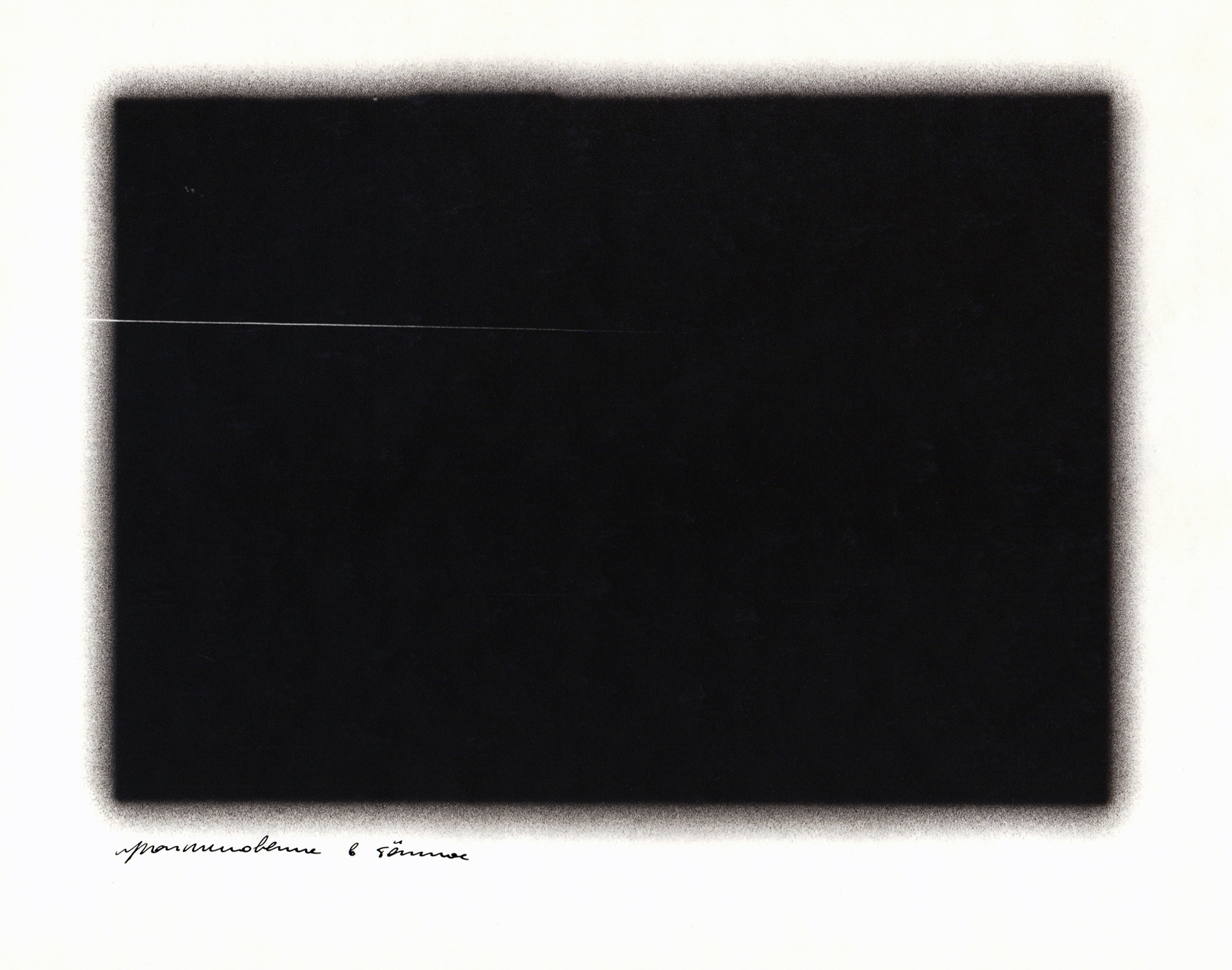

Another important strategy, which also brings the violation of formal principles to the fore, while having different ways of presenting art statements either related to each other or not, can be described as “Photography beyond photography”. Its brightest representative is Igor Savchenko, who announced his refusal to take photographs in 1996, explaining this decision by claiming that by doing photography since 1989 he had already done everything possible by then.[7] This gesture also meant the rejection to create anything new and the search for strategies in order to describe what really existed then or had existed before in the most accurate and complete manner. He also implied a reference to the context – “something that exists around the picture”[8] and, necessarily, to the relationship between people – and it was exactly this which was allowing the reality to take a particular form. It is very important that with such universalization of the language, Igor Savchenko never came to a pure abstraction – all of his “projects of reality” had to do with very specific processes and phenomena (for example, the sunlight) and relationships (for example, between the Russians and the Germans).

Savchenko I., ‘On the altered behavior of sunlight’, 1996

Turning to the medium of photography, and only partially going beyond it (as in the selected project “On the altered behavior of sunlight” (1996), where the image (picture) does not communicate what it was made for – that if why it has textual commentaries) or completely, Igor Savchenko invariably tests the boundaries of his own techniques and research methods. As Olga Bubich writes, photography, along with other methods, begins to serve as “a denouement, a visual catharsis of the story.”[9] As a result, the limits of his own research seem to overlap with the limits of the perceived; shocking viewers and producing a transcending effect on them.

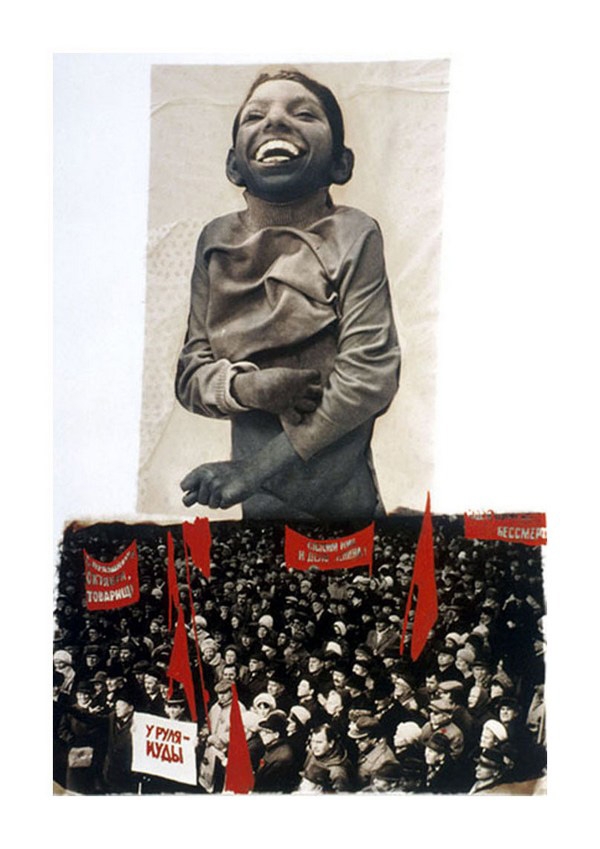

If Igor Savchenko tries various ways of bringing pictures beyond the limits of photography and also in different ways problematizes this “beyond”-situation, Galina Moskaleva and Vladimir Shakhlevich in their project “Madhouse” (1991– 1992) on the one hand, and Masha Svyatogor in her projects made in 2015–2017 – “Kurasovshchina, my love!”, in particular – do this primarily with the help of collage. Both the projects are united by a clear formal relationship between the figure(s) and the background, but the analysis of each allows to move in time and feel its nerve.

A hand-painted photo collage “Madhouse” brings together a “perestroika” rally in the Gorky park in Minsk in 1991 and pictures made at the psychiatric dispensary “Novinki” of the same period. As Vladimir Shakhlevich explains, it was about fixing the “border state” in which Belarusian society found itself in the early 1990s. Combining the images of the rally with those made in “Novinki” as well as adding the red color to black and white photographs brought this state to the limit.[10]

“Kurasovshchina, my love!” reveals a paradoxical interaction of an alienated urban environment and the carnivalized bodily experience of citizens. The artist seems to be trying to invent new ways of bodily appropriation of the alienated urban space of Minsk, without embellishing it. To reach this goal, she makes rather brave experiments with her heroines – mostly women. Comparing both the projects, I would like to articulate the fact of the replacement of the feeling of a “madhouse” with a need for carnivalization as a key life experience in Minsk allowing to overcome social exclusion.

Svyatogor M., from the series ‘Kurasovshchina, my love!’, 2015-2017

“THE REVOLUTION OF THE IMAGE» AND «CHANGES IN THE BODY’S SYMBOLIC FUNCTION”

These projects and techniques also make it possible for us to see how (photo-) images are getting increasingly replaced by (photo-) statements and research. Photography of the late XX century, and above all, photo club photography of the 1970s, was centered precisely around the image, as I have already noted above, its authors were focused on the idea of the uniqueness of the photographic gaze and, therefore, on the originality of the composition and other, primarily aesthetic qualities, trying to use them as a way to rediscover the reality or show it from a new perspective, previously hidden. In this regard, it seems logical to talk about “the revolution of the image” strategy, that can be brightly illustrated with the image “Kizhi” (1971) from the homonymous series by Yuri Vasilyev – already acquiring the status of the iconic one and in some sense prophetic and, therefore, not losing its topicality. Its clear composition combines the dimensions of religiosity and fashion – incompatible then and quite compatible today. Two other examples of the photographs that illustrate “the revolution of the image” strategy are “Unfavourable Outcome” (1972) by Viktor Butra and “Uncle’s dream” (1970s) by Mikhail Zhylinski. Both are extremely aesthetic and, at the same time, phantasmagoric, subordinating the presentation, in one case, the living, and, in the other, the dead to an aesthetic construction, as if taking the viewer beyond the boundaries of a specific space and time.

A new way of human body presentation brings these images together with Vladimir Parfenok’s series “Persona non grata” (1988) already mentioned above and can lead us to another strategy for photography recognition in Belarus, namely to “changes in the body’s symbolic function”. In these works, it is the body that manifests the individualization process, and its specific conditions we can also see – thanks to the context of perestroika present in the depicted interior or some objects, for example, a newspaper one of the sitters holds – and, therefore, understand that these bodies are the most important “participants” in the perestroika narrative itself. Another significant work of this period – Sergey Kozhemyakin’s “Daughter” (1989) expresses a change in the symbolic function of the body as well, although in another way. It seems to be formally leading us out of Viktor Butra’s deadly labyrinth of “Unfavourable Outcome” – it gets kind of reduced in size transformed into a sickle and a hammer and turns out to be something external to the newborn’s body.

A series of body’s transformations in the medium of photography does not stop there, emphasizing the semantic and transformative intensity of the sphere of (inter)human experience. In her project “Inciting Force” (2012) (and, in particular, in her work we are using as an illustration to the text) Zhanna Gladko appears to appropriate a radical artistic gesture, previously belonging mainly, if not exclusively, to male creators. Her work directly refers to the iconic shot from Luis Buñuel’s film “An Andalusian Dog” (1929) where a man cuts a woman’s eye. The difference in Gladko’s image is in the artist’s freedom to own control over her body – her ability to see and be seen independently. In this sense, the whole project can be seen as a challenge to being a woman when holding a male’s gaze and at the same time as the radicalization of this very being – according to the artist, a key (patriarchal) norm of our entire society.[11]

“THE LOCAL ENCOUNTERING THE GLOBAL (MEANINGS AND CONTEXTS)”

Zhanna Gladko’s photo project allows us to move on to the next important strategy for photography recognition today, which I have defined as “the local encountering the global (meanings and context)”. The change in the body’s symbolic function can be considered as the most important dimension of the formation of both individual and collective identities in 2010s. #MeToo and other emancipating movements aimed at giving social and political meaning to female and trans- gender experiences — previously ignored — have intensified the criticism of the normative and objectified body. The development of new technologies, in its turn, has intensified the discourse of post- and non-human bodies. In this sense, addressing these topics in the Belarusian context – here Dzina Danilovich’s “Anatomia” (2012–2016) should definitely be mentioned – cannot be considered outside the global context, and Lorenza Böttner’s[12] documentation of bodily practices can be recalled as one of the most vivid examples. However, the strategy “the local encountering the global (meanings and context)” can be seen as one of the most important connecting lines of Belarusian photography starting from the moment of its recognition outside Belarus. In this regard, the above mentioned photograph “Daughter” by Sergey Kozhemyakin (1989) turns to be significant — in 1991 appearing on “Photo Manifesto” catalogue cover – an album for the homonymous exhibition shown in the Fine Art Gallery in New York the same year. This fact actually made it one of the photographic symbols of the new, post-Soviet sense of time.[13] This image, as well as, for example, Alexei Shinkarenko’s series “Belarusian factography” (2007–2013), was exhibited at the collective exhibition “Opening the Door? Belarusian art today” enabling both internal and external observers to feel the turning point, since in its very composition – in contrast to the newborn and the Soviet symbols of the sickle and the hammer – it was indicating distance in relation to this time.

Another photograph – the so-called “A woman with a flag” (2004) by Andrei Liankevich, an image widely known in Belarus – can also be considered as manifesting an encounter of the Belarusian and the global contexts, since it was this very work that was used as a book cover of German and French translations of Svetlana Alexievich’s novel “Secondhand time”, for which in 2015 the Belarusian writer received the Nobel Prize in literature. This photograph may seem to be devoid of any ambiguity, because, like Alexievich’s book, it speaks of “the red man”. However, this woman’s in red lonely and solemn procession on Minsk main square leaves the question of the fate of the utopian Soviet project also embodied in the modernist Palace of the Republic, vaguely seen in the fog behind her back, and gaining a new capitalist architectural surrounding, no less frightening than the palace itself.

“DISCURSIVE FORMATION OF A NEW SEMANTIC CONTEXT BASED ON DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES” AND/AS “NEW SENSITIVITY”

Minsk urban space, repeatedly mentioned in this research, brings us to its beginning – Arthur Klinov’s photo project “The Sun City of Dreams” (2004) quoted by Lena Prents. 15 years after Lena’s regret of this project’s failing to result in “discursive formation of a new semantic context based on different perspectives”, one can make a timid assumption that this significant transformation nevertheless occurred. The end of the 2000s in Belarus was marked by such iconic photo projects related to Minsk urban space as “And there is nothing left” by Sergey Shabohin (2009), dedicated to art and museum institutions criticism, and “Tabula Rasa” by Sergey Zhdanovich (2001–2011) who presented his interpretation of the issue of emptiness in urban space representation and experience. If we conditionally put these projects on a par with Masha Svyatogor’s above-mentioned series “Kurasovshchina, my love!”, we will clearly see not only the intensification of Minsk photographic research, but also the explicit subjectivation of the research strategies themselves, the transformation of urban space from an object for consideration and critics into a co-subject of the citizens’ personal strategies evolvement.

In the 2010s, the subject of urban space as a co-subject became significant for a number of photographers, who, along with Masha Svyatogor, can be defined as belonging to the youngest generation. Among them Alexandra Soldatova with “The green channel” (2012 – ongoing), Aleksey Naumchik with “We will never get older” (2009–2014) and Maxim Sarychau with “A friend with two paws” (2014) can be mentioned. However, both these and some other important projects made within this decade (“Commemorative picture” (2014) by Alexander Vasukovich, “Forcing the Internet to remember the Holocaust” (2014) by Alexander Mihalkovich, and “Blind spot” (2017) by Maxim Sarychau) enable us to specify the strategy of «discursive formation of a new semantic context based on different perspectives» through the formation of «new sensitivity»[14] context. All these projects can be characterized with not only their sensitivity to various forms of violence most often and, alas, socially normalized in Belarus (it doesn’t matter whether intentional cruelty to animals or police’s outrage are drawn attention to), but also the photographers’ desire to talk about everyday life so as not to multiply stereotypes promoting discrimination and dehumanization of people and their life forms that do not correspond to glamorized or ideologized patterns, or repressive social and cultural norms.

“New sensitivity” also often goes alongside with a number of other strategies for photography recognition in Belarus – at least with “changes in the body’s symbolic function”, “the local encountering the global (meanings and contexts)” and “photography beyond photography”, which can actually serve as an indicator of discursive formation of a new semantic context based on different perspectives, possibly thanks to this.

Today this context raises other issues, far from being related to photography only (those on domestic violence, social inequality, alcohol dependence, aging, autism and many other phenomena and dimensions of life), the artists have something to comment on; the ability to put themselves in other people’s shoes, and, due to this, make both – themselves and the audience – share the pain of those who suffer, is considered the most important goal of art. Nevertheless, Belarusian photography today does not follow a single recognition strategy and solves very different tasks that equally deal with the form and the content. The presence of various recognition strategies allows us to see both continuity and inevitable gaps and splits in various projects and also put them in a wider artistic and social context, making visible the fact that photography defines and performs very different and important tasks in society.

The text first appeared in the book The history of Belarusian photography, ed. Hanna Samarskaya, Antonina Stebur. – Biruliškės, Kauno r. : Kopa, 2020.

[1] It was prepared and shown for the first time by Lithuanian curator Kẹstutis Kuizinas in Vilnius Contemporary Art Center at the end of 2010 – the beginning of 2011, аnd then, in 2011, at Zacheta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw.

[2] Prents L. Оn misconceptions // Opening the Door? Belarusian Art Today. Vilnius: Contemporary Art Centre, 2010. P. 59.

[3] The strategy «The revolution of the image» was introduced by Hanna Samarskaya and Antonina Stebur.

[4] Unlike Belarusian photography of the first part of the XX century, which still needs to be investigated.

[5] Reut I. «Minsk school» or «New wave»? Belarusian photography in the 1980s-1990s // Creative photography in Belarus / V.P. Parfenok. – Мinsk.: Аrtia Grupp, 2014. P. 193.

[6] This can be confirmed in Andrei Liankevich’s own words: today the photographer “sits in front on his computer, conducts some research, communicates with experts, and then, based on this huge amount of information, makes illustrations, for example, using photographs. […] As a result, photography becomes a kind of object that illustrates what you wanted to say”(A. Liankevich. Photography as photography today (09/05/2012) // European Cafe: Open lectures and discussions, http://eurocafe.by/lecture/2012/09/06/ lektsiya_andreya_lenkevicha).

[7] Reut I. «Minsk school» or «New wave»? Belarusian photography in the 1980s-1990s // Creative photography in Belarus / V.P. Parfenok. – Мinsk.: Аrtia Grupp, 2014. P. 207.

[8] Three days with Igor Savchenko. Day 2 and 3 // From the series «Meeting the legends», ZNЯТА, https://znyata.com/z-proekty/legends-savchenko-2.html

[9] Bubich О. Igor Savchenko: conceptual series «Invisible», 1992–1994 (04.06.2015) // ZBOR, http://zbor.kalektar.org/4/

[10] See Bubich О. Galina Moskaleva and Vladimir Shakhlevich: a series of photographs «Madhouse», 1991–1992 (18.05.2015) // ZBOR, http://zbor.kalektar.org/1/ Moskaleva G. and Shakhlevich V. from the series “Madhouse”, 1991-1992

[11] Prafota. Ist Project Photography Contest. Kaunas: Taurapolis, 2015. P. 88.

[12] Lorenza Böttner (1959-1994), originally named Ernst Lorenz Böttner, was born in Chili into a family of German origin. At the age of eight, s/he received an electric shock, as a result of which both the arms were amputated below the shoulder. Böttner refused prosthetic arms, but developed an acute interest for dance and painting using the mouth and feet. In the dancing practices, s/he openly affirmed her/his sexuality, investigated impaired body experience, the issues of disease (AIDS) and transgender feminist existence. For more details see: Documenta14, https://www.documenta14.de/en/south/25298_lives_ and_works_of_lorenza_boettner

[13] Reut I. «Minsk school» or «New wave»? Belarusian photography in the 1980s-1990s // Creative photography in Belarus / V.P. Parfenok. – Мinsk.: Аrtia Grupp, 2014. P. 212.

[14] See my text on this generation of Belarusian photographers: Shparaga, V. PRAFOTA Contest: From Emotions to Storytelling // Prafota. Ist Project Photography Contest. Kaunas: Taurapolis, 2015. Pp. 32-37.

Imprint

| Index | Zhanna Gladko Оlga Shparaga |