Two days after the opening of the exhibition We, the people at Central Slovakia Gallery in Banská Bystrica, the Polish president Andrzej Duda claimed that the European Union is ‘an imaginary community from which we do not gain much’. These recent political statements made in Poland framed the reception the exhibition We, the people, though of course there are many other possibilities alternatives of what a ‘we’ could be and how unity is operable. Let’s assume that the aforementioned event is not important in it of itself but can be understood as a symptomatic reaction, an act of speech that performatively creates a discourse around and about communities. Andrzej Duda’s position would rather lead to other imaginings and alternative reflections on what a unity actually could be outside of the net of the power of the EU.

A smooth sentence

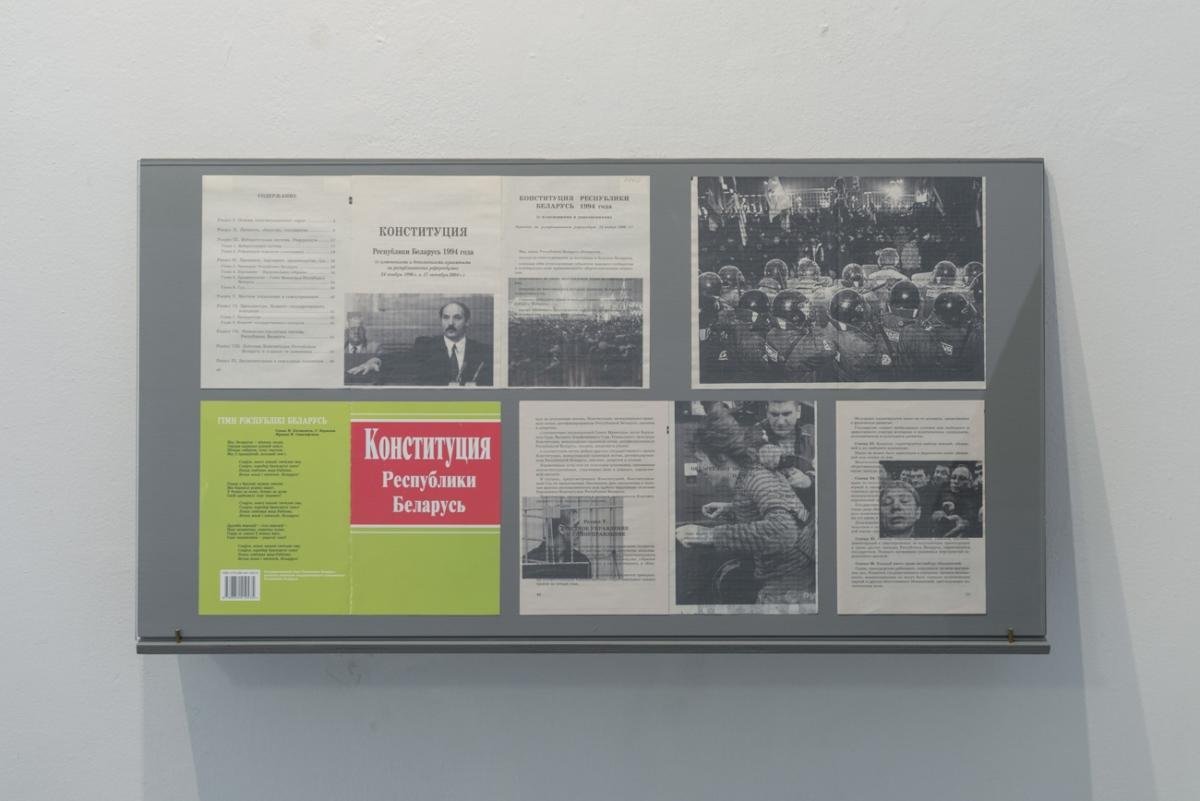

The preamble to the Constitution of the United States of America begins with the phrase ‘[w]e, the People’. This introduction suggests that union and equality of subjects formed the base of a hierarchy of values. The beginning of the second constitution in the world, often identified with a first democratic document, configured a textual understanding. However, as one can read in the curatorial statement of the exhibition, this smooth sentence can be both useful and dangerous. In practice, it is an empty, mechanically repeated slogan that covers over the reality of oppression and inequality. The phrase, in short, is a simulacra – a process which is visualized especially by the work of Marina Naprushkina Constitution of Republic Belarus in Images (2012). The cited work also starts with the same motto and guarantees a bunch of rights that are not enforced and in the end turn out to be dead letters. Naprushkina juxtaposes that the phrases with photographs that document violation of laws by public authorities: aggressive suppression of demonstrations by the police and unjust, show trials. In this case, the pictures become indexes that refer to ‘reality’, fissures that expose ‘the real’.

The law operates in language and has a performative and complex influence on individuals. Agnieszka Kilian, the curator of the exhibition, treats philosophy of law and its practice as a critic tool that enables understanding of socio-political events. She likewise also uses law to interpret narratives about the contemporary patterns of power. She uses the quote ‘we, the people’ as an anti-motto and clashes this general sense of unity with private stories of individuals that confirm examples of exclusions and injustice.

‘You must be paranoid’

The slogan ‘We, the people’ was written just under the entrance of the display and resembled maxims placed on public buildings. This visual structure recollects the Enlightenment’s origin of ideas on democratic states with its presumptions of the rationality of human subjects, the role of language (we can imagine a hypothetical different system of a law), faith in universal rules and abstract notions. This seemingly transparent ways of thinking have their obvious limitations. For instance, in the first constitution of Poland, the power was given to ‘the nation’, but in the document, three different definitions of ‘nation’ were included that were mutually exclusive: the nation as all stated and nation as only an aristocratic state. ‘We’ does not refer to all subjects, and automatically separates. One of the most striking works of the exhibition is Free, white and 21 by Howardena Pindell (1980). The American, a black artist, who suffered from amnesia after a car accident, underwent a sort of self-therapy by performing for the camera. The film consists of her memories about the discrimination she experienced during her life. Pindell leads a dialogue with a white woman that responds curtly. The interlocutor looks like a conservative, white lady from the 50s or 60s and refutes Pindell’s words by saying: ‘you really must be paranoid’ and ‘you won’t exist until we validate you’. Finally, the disputant removes the disguise, and it is revealed as the artist herself. In this first case, the age of the ‘Other’ has a symbolical meaning – Pindell was 21 during the civil rights movement in 1964 and this age is also when someone reaches the status of a full adult in the USA. Secondly, the artist shows the mechanisms that justify discrimination. Concealed discrimination is more difficult to prove and the subjects who are higher in the hierarchy overlook these complaints, blaming the victim (‘you must be paranoid’). The status quo often leads to the escalation of violence. Thirdly, after being brought up in a racist society, the discriminant ‘Other’ is being internalized and treated as a perfect model and a source of self-harm (the white woman turns out to be Howardena Pindell in disguise). Fourthly, the story has a bittersweet taste, it is sad and funny at the same time. Pindell makes her conservative opponent look funny, she mocks her and uses pastiche as a very mighty political instrumentality – that conservative actors are especially afraid of. This is the point: laughter is a means to achieve justice; it is an individual, corporal gesture (see: P. Mościcki, Humor: wdzięk roztargnionej ludzkości, „Dwutygodnik”, No. 248, 10/2018). Though an act of laughing is very personalized, Walter Benjamin wrote that humor performs justice without the need of a judge or even any words. He claimed that a despot was an ideal subject of humor, because in his case ‘judgment and enforcement are united’ (see: ‘Der Humor’ from 1917/1918). That is, especially true in authoritarian and totalitarian political spheres where humor becomes a way to set justice, in case it is undermined.

Wilhelm Reich claims that fascism is a human tendency, a feature that is global and has its source in the unconsciousness. What is more, it is an extreme expression of religion and sexual prudery, easily cultivated in patriarchal families. Bang, bang! Pow, pow!

Bang, bang!

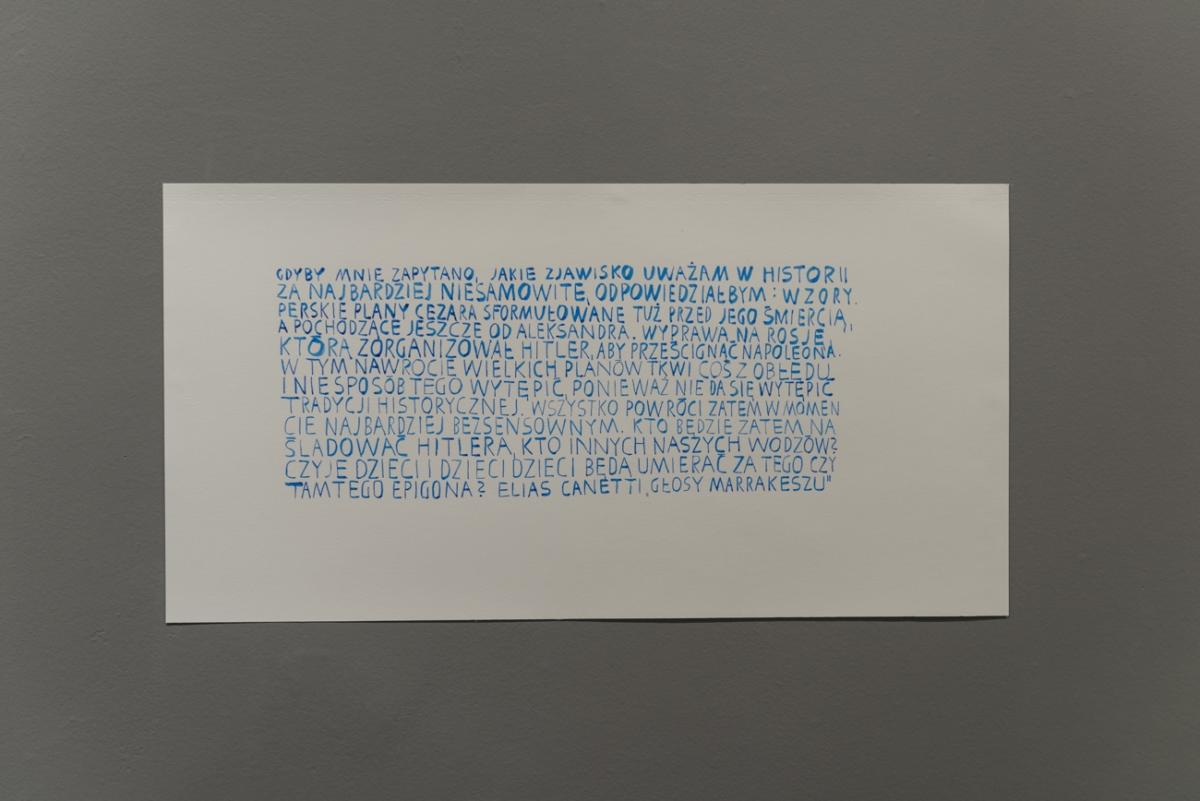

The poetics of comedy could also be a forceful means to show the absurd face of a totalitarian ideology – this idea could be one of the keys to interpret Mateusz Kula’s object#2 from the series Comedic Aspects of Fascism (2018). It consists of a piece of furniture from a set called ‘wall unit’, which was very popular in the democratic republic in the 70s and 80s and filled with many tchotchkes that look rather innocuous: plastic toy guns (Parabellum), Easter eggs, Humpty Dumpty or fantasy literature, Nazi memorabilia. ‘I think that dirty and unwanted – much like repressed – is very powerful. […] [i]t seems to me that if we manage to include these things in truly dramatic art or work with them using comedic methods, then there’s a chance that they won’t come back to us in the shape of political nightmare’ – Although he spoke in this interview with Marta Lisok (U-jazdowski Project Room, 2017) about his different work, it seems that he had thought about similar mechanisms. A Sound Buffer that emits low notes makes the whole piece of furniture tremble and could be understood as a symbol of energy of objects that can transmit ideologies almost imperceptibly. They shape the behavior of children and youngsters, and as Wilhelm Reich says in his Mass Psychology of Fascism, one should examine visual aspects that are hidden patterns of social attitudes before they are verbalized. But devotional articles and fascism? Isn’t it paranoid? Reich claims that fascism is a human tendency, a feature that is global and has its source in the unconsciousness. What is more, it is an extreme expression of religion and sexual prudery, easily cultivated in patriarchal families. Bang, bang! Pow, pow! All these tiny objects, conduits of fascism, found by the artist in Banská Bystrica, are used as children’s playthings.

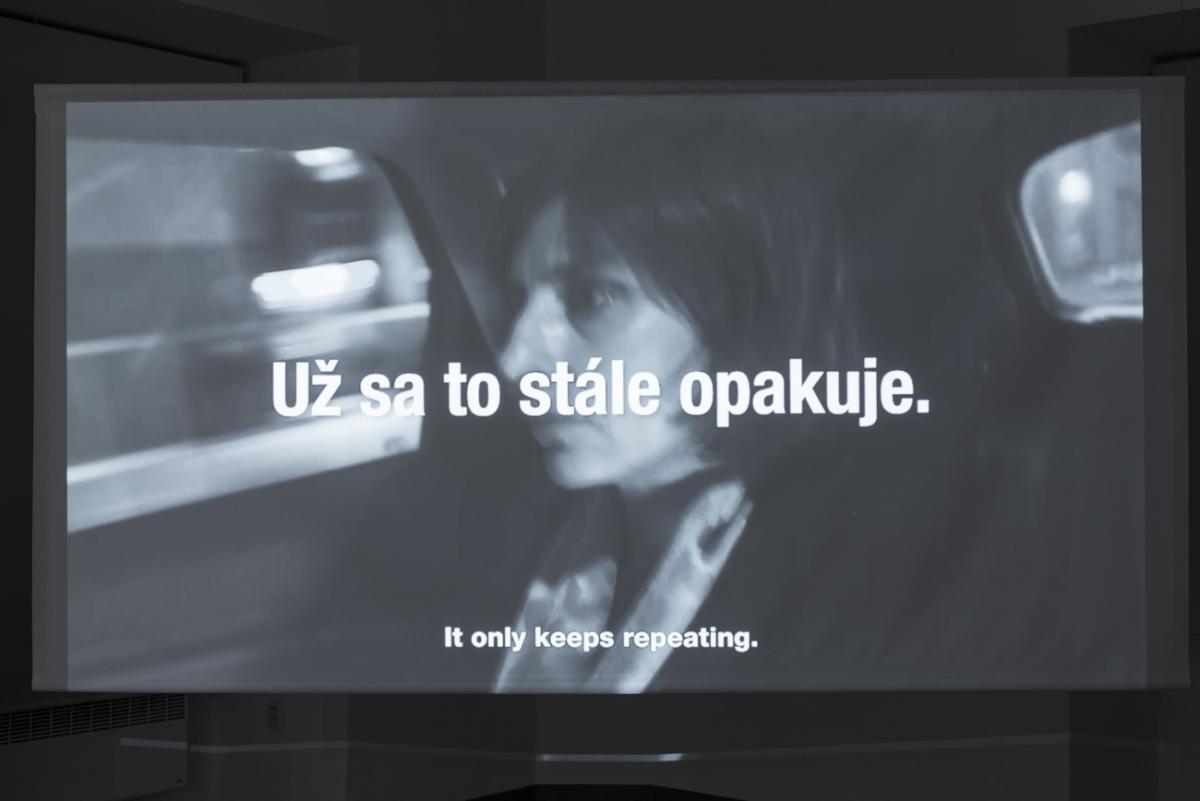

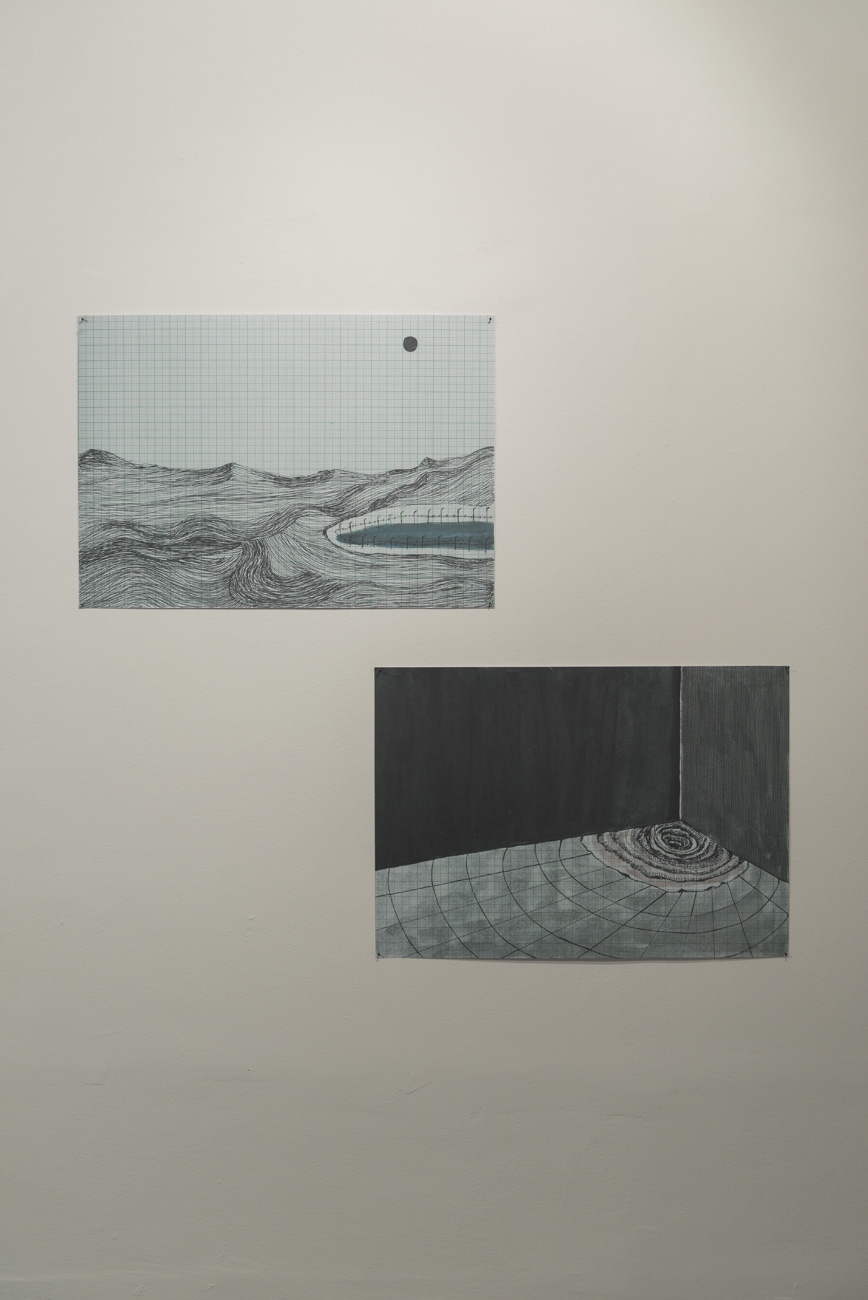

The entanglement of religion and fascism is significant in the context of clerical fascism in the First Slovak Republic. Ivan Jurica and Anton Čierny recall an issue of a popularity of neo-Nazi rhetoric and a popularity of the nationalist movement (‘Before the Parliament is Set on Fire’) in Slovakia nowadays, especially in Banská region. The artists exploit fragments of popular anti-Nazi films from the communist times (50s – 70s), using phrases spoken by Nazi characters. The dialogues from films like The Shop on Main Street (1965) are set in selected places that refer to Slovak’s identity: for example the source of ‘national’ river Nitra. This simple gesture allows one to observe similarities in verbal narrations during the second world war and today and draws attention to a troublesome fact that Slovakia’s first state structures were formed under Nazi occupation. In this work, as well as in Agnieszka Piksa’s selection of drawings (Untitled, 2010-2017) fascism is a kind of pattern, spectre that has been haunting any kind of community.

The entanglement of religion and fascism is significant in the context of clerical fascism in the First Slovak Republic. Ivan Jurica and Anton Čierny recall an issue of a popularity of neo-Nazi rhetoric and a popularity of the nationalist movement in Slovakia nowadays, especially in Banská region.

‘Are you calling me a dog?’

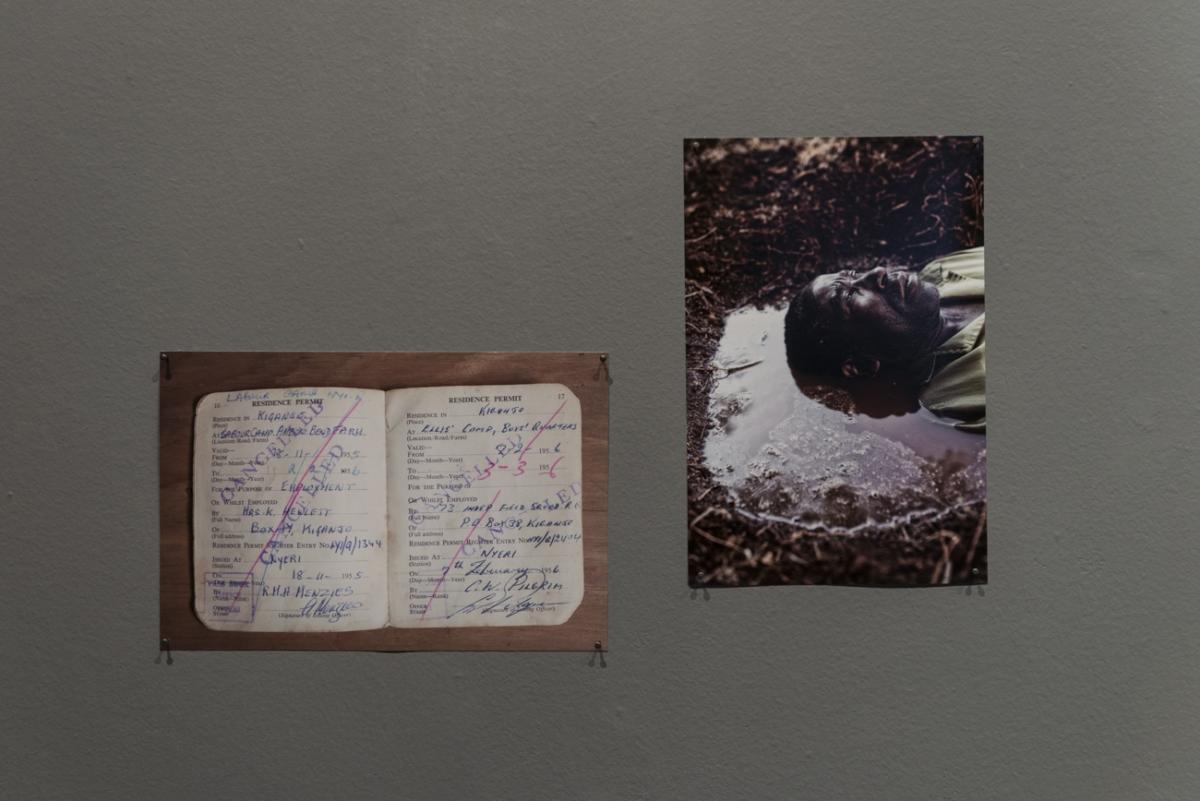

Where does the qualitative difference between ‘basic needs of prevention’ and ‘oppression’ lie? The topic of terrorism appears in a film of Joanna Rajkowska’s Upwards! (2006) and Kama Sokolnicka’s Amir Ageeb (2018). They show a series of procedures that dehumanize an individual in a state of exception, when human rights don’t prevail. This is also an aspect of a project of Nura Qureshi Are You Calling Me a Dog? (2017), which reimagines the history of The Mau Mau Resistance in Kenya that documents a chain of events that accelerated independence. The title is associated with tactics of humiliation . After nearly 60 years, Qureshi tries to recapture the event by using objects (proofs) and reconstructing topical scenes. The tactic of re-enactment, which invites one to ‘go back in time’ similar to role-playing, is also visible in Upwards! and Amir Ageeb. The second work is based on the artist’s reconstruction of the corporal position of Ageeb, who suffocated in 1999 due the position he was placed in during his deportation. Empathy or ‘entering into’ the position of ‘the Other’ is a method to resist oppression generated by closed communities. A body as a whole, recalcitrates technologies and regulations that fragement the body. No law or technology exists that reflects the body as a whole entity (as Costas Douzinas writes in a text ‘Human Rights and Postmodern Utopia’ noted in the reader Dreams & Dramas edited by Kilian). The law sees only body parts: ‘reproduction laws’ divest a womb from a whole women body, physical work is visualized through hands. This motif appears in Dorota Kenderová’s film still, a part of an installation There Are More Things (2018, in collaboration with Jaro Varga), that depicts a human body without hands.

The exhibition was coherent, austere in a frugal curatorial gestures, but these aesthetics suit the topic. It likewise reflects global views that extend far beyond Central Europe’s standpoint. While concentrating on critical perspectives, it also charitably suggests some solutions (methods of resistance). The first device is to focus on the private body, but the second one implies that the only possible remedy for crisis of the world is to remove the human entirely. This landscape ‘after the human’ appears in the works in the final room of the display: prints of Rupali Patil (People, Unpeople, 2018) and Jaro Varga’s wallpaper of a mine with the tools of the trade. These scenarios, peaceful and silent, look dangerously complete without humans.

Imprint

| Artist | Anton Čierny, Ivan Jurica, Mateusz Kula, Marina Naprushkina, Rupali Patil, Agnieszka Piksa, Howardena Pindell, Nura Qureshi, Joanna Rajkowska, Kama Sokolnicka, Jaro Varga & Dorota Kenderová |

| Exhibition | WE, THE PEOPLE |

| Place / venue | Central Slovakian Gallery, Banská Bystrica, Slovakia |

| Dates | 19/09 – 4/11/2018 |

| Curated by | Agnieszka Kilian |

| Index | Agnieszka Kilian Agnieszka Piksa Anton Čierny Central Slovakian Gallery Dorota Kenderová Howardena Pindell Ivan Jurica Jaro Varga Joanna Rajkowska Kama Sokolnicka Marina Naprushkina Mateusz Kula Nura Qureshi Rupali Patil Wiktoria Kozioł |