The following text was written by Kateryna Iakovlenko on February 19, 2021, when the ongoing pressure from the Russian government to escalate its already 8-year-long war with Ukraine was reaching its height. The events of today’s early morning, indicating a new phase of a brutal, illegal and shameful aggression are devastating to us, but will not leave us speechless. We stand together with Ukrainian artists, culture workers and all citizens of Ukraine in their homeland and abroad. You are not alone in this horrible situation; we hope for and demand strong solidarity, both in gestures and in actions, from the international community.

Editors of BLOK Magazine

My everyday life is tightened as if with a hard tourniquet around my neck. It makes it impossible to speak, impossible to scream, impossible to breathe, and impossible to eat. Lack of air in the throat breeds hatred. These days the Ukrainian reality that passes through the newsfeed, radio, podcasts, conversations with friends, through the air, through work, walks, sports, art — all this, along with my food, comes back, refusing to be digested in the body. During the eight years of war in the Eastern regions of Ukraine, I thought that I was prepared for different scenarios of ongoing war — but it turned out that even if the brain can hear the information, the body is not ready to process and resist it.

Feminist theory sees food and eating disorders as closely related to power, emphasizing the close links of the body and bodily behavior, with violence. For example, the German researcher Bettina Steiner considers the refusal of food as a way to control your own body, to be its subject. In other words, the refusal to eat is one of the strategies of undermining, or, as the author herself calls it, is a strategy of survival. In other words, moral experiences are processed in the body and rejected – the protective reaction produces purification.

In my case, emotional anorexia is a refusal to consume not food but rather the impossibility of facing the fiction-reality, a space where things such as fake news hides the truth, war renders resolution impossible, and fear influences dreams and visions of Utopia. I am asked to tear my life and my memories out of my body and present them in a completely different way. When the annexation of Crimea and the first protests financed by the Russian state began in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, it seemed to me that my hand had been cut off. And although both my hands were in place, the pain from this surreality drowned out inner feelings. For me, as a journalist at that time, it was essential — because it was connected to the impossibility of writing. Three years later, after a series of events, including those connected to the war, it seems that I had a hole in my body — my whole body was not just empty, I felt the cold winter air penetrating my bare corpus, touching my muscles, viscera, and blood.

Since 2013, many Ukrainian artists have chosen to turn to the documentary and archival as their strategy — to expose the facts, to speak hushed truths. Over these long eight years, our journalists have mastered fact-checking. And now our media disputes the evidence of Russian propaganda and validates Russian aggression. All this is presented in tables, numbers, videos, and photographs. But how do we convey other facts — the fact of emotional suffocation, anxiety, confusion, which are associated with incredible confidence in one’s own dream, love for one’s loved ones, one’s culture, one’s country, and most importantly, freedom — which we are called upon to defend every time, by going out to Maidan? It seems to me that I am still looking for words and images that can be used to describe this experience of living in suspense. And to convey that incessant pain in the muscles of the whole body and the tastelessness and rejection of food.

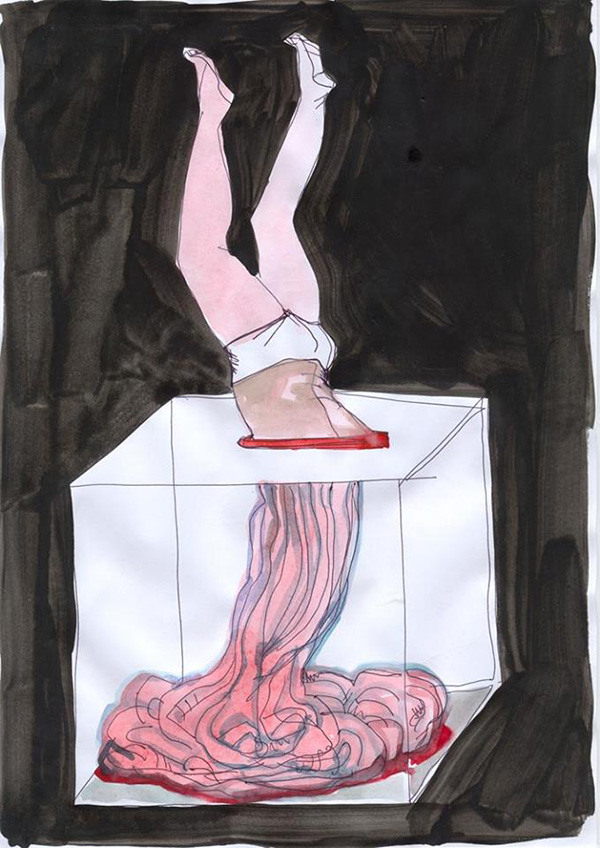

These days I am looking at Ukrainian artist Vlada Ralko’s Kyiv Diary, which she worked on during the Maidan atrocity. The artist’s diary is an expressive and emotional statement about revolution and war. Each of her images provokes the viewers, immerses them in a revolutionary atmosphere. There are images of women gagged with candy grenades, another woman throws herself into a meat grinder. Another one is literally turned inside out, along with all the violence and horror she observes around her. Here, the body becomes flesh; it absorbs itself and heals itself. Looking at these images, I feel perfectly how my body mirrors the pain of the depicted women. If Susan Sontag wrote about illness as a metaphor, then I would pay attention to how war itself becomes a disorder or a disease. In this case it is directly related to the sensations of the body and its resultant physiological symptoms.

Brutally describing the cruel reality of the female body, Ralko creates a vivid image of rejection, vomiting out her heroines to protest and protect them from the violence. And so, to drown out the inner pain, they turn to physical, bodily pain. In order to protect herself and her loved ones, the women protagonists of Ralko’s paintings reject their body, skin, and insides. For Vlada Ralko, a woman is not just a mother, not just a sister or friend; a woman is the personification of the earth and land in the first place.

Touching upon the topic of the refusal to eat, I would recall another work Synonym for “wait” performed by the Open Group (Yuriy Biley, Stanislav Turina, Pavlo Kovach, Anton Varga) during the Ukrainian national pavilion Hope! at the Venice Biennale in 2015. The group sat at the table and refused to eat. Watching nine monitors which were broadcasting from the houses of the Ukrainian military, they stood in solidarity with their families. The artists were waiting for the soldiers to return home.

Today, we are all waiting at that table.

Reading books about the food of World War II, such as How to Cook a Wolf (1988) by M. F. K. Fisher, I see how food during times of war becomes a way that helps us hold on to reality, it becomes a way to defend it, a way to feel some kind of pleasant emotions. According to the author, the process of cooking or the ritual of eating food provides warmth on a symbolic level. Strictly speaking, the warmth of food passes into the body of a person who then feels warmth and hope in relation to their future. Food creates rituals that bring peace and stability in unstable times.

Food is never something separate from politics. It is always a survival strategy, even if this survival comes at the expense of the body itself.

After reading the news about the alleged evacuation of people from the Ukrainian uncontrolled territories, I called my parents, who are still there, and asked about the situation.

“It’s all right” — says my mother — “I put the kettle on to make tea”.

Edited by Ewa Borysiewicz and Katie Zazenski