Aurelia Nowak: You are not yet widely recognized in the art world, but in Szczecin, you are known for Artistic work is in progress here, your impressive diploma project from last year. I think that is the reason you were invited to this year‘s edition of the {Project Room}. Could you tell us more about that project?

Karolina Babińska: For some time now, I have been interested in the information that is contained in the materials from which various objects are built. At one point, I noticed that objects communicate; they tell us about many things. For me, most crucial was the notion of affordance, derived from cognitive psychology. It refers to the properties of objects themselves and of human perception (but not only human), in relation to the recognition of specific potential uses of objects. The most interesting thing for me is that we see this potential without even realizing it, before actually using the object. This is a dormant possibility. It is due to the fantastic human ability to use and create tools; from a walnut shell, where we can see the potential of a water container, to the intuitive operation of ATMs. Research into this phenomenon is helpful in industrial design, but also in completely new areas – for example, in human-computer interaction. I was fascinated by the interaction between use, usability, uselessness, blocking of use, and so on, how usefulness and its perception are determined by cultural experience.

This fascination accompanied me while working on my diploma. In asking why and how objects are used, we can also ask about the purpose of art and the artist, and their potential roles. My diploma project is a model of how I understand artistic activity, how the artist‘s work looks in comparison to other professions. Wanting to talk about it, I worked for three months in the hourly-wage system at sites where art was non-existent. I created site-specific installations, using free or almost free materials found on the spot or thrown away by someone. I wanted to bring about a situation in which only the artistic work would be valued, regardless of the cost of the material used, regardless of the subject it discusses, and regardless of the low prestige of the location. At the end of each month, I invited guests to I leave my workplace – i.e. the event ending that stage of work – then I destroyed and threw away the installation, to start the whole process anew the following month. During my diploma show at TRAFO, the main art institution in Szczecin, I presented single modules – remains of packaged materials – closed in a compact portable kiosk. These acted as the elements on which I could base my presentation of my “workplaces” to the audience, so that they could picture the whole installation in its most interesting form, presented in this alternative interior. I treated the presentation as a paid two-hour performance, preceded by a contract for almost 15 PLN, co-signed with Stanisław Ruksza.

My manifesto, my declaration, was to propose loss as a value. In my opinion, the most attractive things that happened over the course of the months I spent in free and non-institutional spaces, while the presentation of insignificant fragments in a state-funded institution, paid for with taxpayers‘ money, acted as a suggestion for the viewer – to recognise this loss as a value. I imagine that the most interesting phenomena in art exist outside institutions, and even if we can see really good works of art and great artists in institutions, it is only a glimpse of what is now most interesting in contemporary art. Beginning with affordance and the information for the user contained in material and objects, I came to thinking about the function of art and its relation to other objects and areas of life. “Useful” and “practical” are often also “efficient” and “profitable”. There is often an equal sign between “profitable” and “valuable”. I wanted to locate the point where “useless art” is the most valuable.

Your diploma was largely based on the fact that the viewers who only saw the show at TRAFO could not fully experience that project; they could only ask the insiders about the previous presentations. However, I feel tempted to ask you what exactly one could see in the sites where you worked during those months.

I decided to use the institution and its functions as an inspiration for action. I focused on utility items. The transformations of these items were derived from the manual gesture, and to some extent, from the behaviour of the material from which they were made.

The first of the three places was a defunct clothing store. I decided that the objects that would fill the space during my working hours would refer to the previous function of the place. I cut and reworked most of my clothes, but I also used my almost-daily deliveries – i.e. items left outside by the residents of the block of flats where the shop was located. This annexation of things was extended with the annexation of any inspiring traces left by visitors to my “workplace”. I pulled pieces of fluff from clothes or transformed ice cream cones into sculptures – I phished “work” from the viewers who visited the place.

The next space was the hall at Technopark Pomerania, in a building in the complex of office buildings designed for Szczecin‘s start-ups. I sat on green linoleum or a green company armchair, and I punched or stapled notes from my legal studies with an office stapler and arranged them in complicated cascades suspended in space, or I constructed models of furniture from recycled paper in 1:1 scale. While sitting in this hall, everyday, I was passed by Technopark employees entering and leaving work, offices, and business meetings or going for lunch. I was almost unnoticeable to those busy IT specialists, graphic designers, programmers, marketers. Unexpectedly, the greatest friction occurred between Artistic work is in progress here and the building‘s administration, organizational and PR manager, and health and safety manager. The good will of both sides sometimes turned out to be insufficient in the face of strange obstacles, such as the lack of permissions to work at high altitudes, i.e. the possibility of suspending anything from anywhere higher than a chair. I notoriously forgot about that regulation. Thus, I unconsciously ignored the norms imposed on employees in complex work environments, incompatible with creative work. In the second place, I created objects using the principle of mimicry. I tried to become more like the environment. I worked with office and organic materials, creating a specific paraphrasing of the word Technopark. I also used ice, plasticine and green plastic, adhesive tape, office clips, elastic rubber bands, jars, self-adhesive cards, and flageolet beans.

The last “place of work” was the premises of a former language school. There, I also used the existing architecture and objects. The leitmotif of that place was specifically understood exoticism. Exotics in the Polish sense, i.e. often reduced to a last minute trip to Greece or just a potted ficus.

In your artistic practice, context is very important. It may be a specific place, a socio-cultural-political situation, but sometimes it is also a joke made from someone else‘s invitation to participate in an exhibition, as in the case of the Friends project, when Łukasz Jastrubczak invited you and your female friends to organize an exhibition in the Obrońców Stalingradu 17 gallery in Szczecin. How was it with Do It Yourself in the {Project Room}? What was the context in this case?

The context was the invitation itself, the very concept of an exhibition at an institution as a way of presenting art. The tradition of conceptualizing the exhibition as a theme, action, or – directly – the artist‘s work is already very long-standing, but still inspiring to me. I found the {Project Room} empty, so I decided to use the institution and its functions as an inspiration for action. I focused on utility items. The transformations of these items were derived from the manual gesture, and to some extent, from the behaviour of the material from which they were made. Of course, it is difficult to reduce any institution to the building and infrastructure only, which is why relations between people such as the curator, the director, the artist, and her work were also materials in my exhibition. I also included media messages and promotional materials, the narration of the exhibition.

How do you work? What do you need most while working on the concept of an exhibition?

I look at the situation I am in and look for a reason why I should create something. I wonder what I can come to understand from this particular situation, what kind of problem will become clearer for me or more precise. I am thinking about how to find more general references in such a situation, those which concern more universal phenomena.

The objects you have created, which are found on the way to the {Project Room}, blend in with the environment. Spectators must be very careful to distinguish them from objects that are not art. Tell us about what can be found in the corridors of U–jazdowski and what was the most important aspect for you.

From the entrance through the main door, in the corridors and staircase leading to the {Project Room} itself, the viewer encounters objects that either replace the existing ones or act as additional elements in the space, but they are always virtually useless or pseudo-utilitarian. I tried to distort not only their form, but also their function. I thought that the more useful a form is, the more precisely designed for a specific purpose, the more easily it can perform a variety of persuasive functions, encouraging specific user reactions. Such methods are related to marketing, market-oriented activities and logic, or propaganda. I also thought about the aesthetics of these objects. Deformed tin poster displays, fonts used in the inscriptions on the walls, three additional pouffes – thanks to which the seat in the corridor became mobile, an armchair with short legs in which a table for leaflets “sits down”, an eco-leather shelf for information brochures, a chair cushion for the person watching the exhibition in the shape of a wedge of fat from Beuys‘ conceptual work – all these things were haptic and resulted from the material out of which they were made.

I tried to distort objects from the perspective of what they can be used for. One could say that they seem naïve or inert – in this sense, I wanted to use aesthetics to convey the impres sion of some kind of impotence, the limit of a certain form. It was the objectivity and materiality of these actions that was supposed to tell the story of the limits of certain possibilities. My question was: and what if it is impossible to squeeze out even more efficiency, effectiveness, profitability because of the resistance of the actual material? What if it is beyond our power? Thus, perhaps we could see some standards as simply overstated and attempts to comply with them as irrational.

It was also different for me to work within the budget assigned to the participants of the competition. The actual cost of purchas ing and installing the suspended ceiling in the {Project Room} (very efficiently, within three days, by a team of Sudeten high landers) forced me to make the rest of the objects myself. In this context, it is very clear that the title Do it Yourself was fulfilled.

Do It Yourself is actually your institutional debut. However, the title of the exhibition shows a somewhat sceptical approach to the issue of artistic production and the structures that you faced while in collaboration with U–jazdowski. Do you think it is impossible to create something interesting in an institutional context?

I think that the expectations for public art institutions are very high. But there is just as much faith. Certain actions are only possible through institutions or with the help of an institution. In a sense, it is good to know that the phenomena of institutional critique have their own quite safe place in the circulation of art. It is good to have this “where, if not here” certainty based, for example, on the existence of the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art. But it may be more timely to address the lack of trust in public institutions in a more general sense. One can promote scepticism and distrust in the public sphere, but one could also invest even more energy in self-organization, grassroots initiatives, associating beyond any general or universal plan. The obvious consequences of self-organization are an increase in responsibility and a sense of agency. Although it is socially difficult to build something larger than a local road with a grassroots initiative – and the scale of an artistic event may be confined to one and a half artists and five spectators – I believe that “thinking on one‘s own” may be a postulate that can be fulfilled. However, such an approach should define which goals and appetites are realistic. In this perspective, instead of Think Big, let‘s suggest Don‘t Think Too Big. I suspect that realizing opportunities and potentials may prove to be the most efficient social project.

Showing the resistance of matter is a way for me to rationalize it. On the other hand, reality sometimes seems so surreal that the most daring and imaginative forms and visions of artists seem to be far behind it.

You also address the pressure of success and professionalism in the art world. I think it is interesting in the context of your first institutional exhibition. Your objects in utility spaces on the way to {Project Room} and interference with the visual identity of U–jazdowski give the impression of be ing very unprofessional. What were the reactions of viewers and the institution?

Professionalism coming out of distortions and imposed forms was described as “funny” and “ridiculous”, but also “brutal” and “thoughtless”. For me, it was important that the visible error had an original, handmade character. It was also a consequence of the material used, what its characteristics were. I wanted to highlight the limitation of the material and try to bring the topic – i.e. the situation of the exhibition in the {Project Room} – to the most direct form, to the material. Showing the resistance of matter is a way for me to rationalize it. On the other hand, reality sometimes seems so surreal that the most daring and imaginative forms and visions of artists seem to be far behind it.

Already at an early stage in their career, young artists are required to communicate with institutions and to be able to tell stories about their projects. Do you feel ready for this type of cooperation?

This is a very important question! It is especially important at a time when it seems that the perception of many phenomena, not only in the field of art, is based on how they are spoken about. I am aware that many seemingly historical and established facts are being reinterpreted. Even if such a practice has a centuries-old political tradition, its contemporary iteration is extremely interesting. Narration about art, as well as speaking about one‘s own work, is treated not only as a symptom of professionalism, but also as an integral part of the artist‘s practice. And if so, just like any other element of a given work or exhibition, it may be subject to dismantling, artistic manipulation. Wouldn‘t it be reasonable to ask what professional communication means from the artist‘s point of view? Or maybe the artist‘s professionalism requires an analytical and sometimes subversive approach, revealing the patterns of language which cease to be transparent, so it becomes possible to see it as a tool of expression, creation, but also manipulation and persuasion?

As a complement to the Do It Yourself project, you offered me and Jarosław Lubiak (Artistic Director of U–jazdowski) the opportunity to participate in a performance during the opening of the exhibition. We were supposed to change roles – you said what I said, the director said what you said, and I had to say what the director said. What was this ex change for you?

My goal was to dismantle our situation. Me as an invited artist, the director of the institution as an inviting and ennobling entity, and the curator acting as an intermediary. The change of roles was supposed to foster a new way to look at the situation and make the perspective more abstract. I imagine that such a model can be useful as a tool in other situations. Perhaps art and aesthetics in general can be useful as tools for interpreting everyday social situations. If they offer the possibility of disrupting patterns, then relations and hierarchies considered permanent can be seen as negotiable. This act, which could have been seen as a brutal injection of statements from one person into another‘s mouth, was intended to be an opportunity to show the various kinds of pressure exerted on these and other entities.

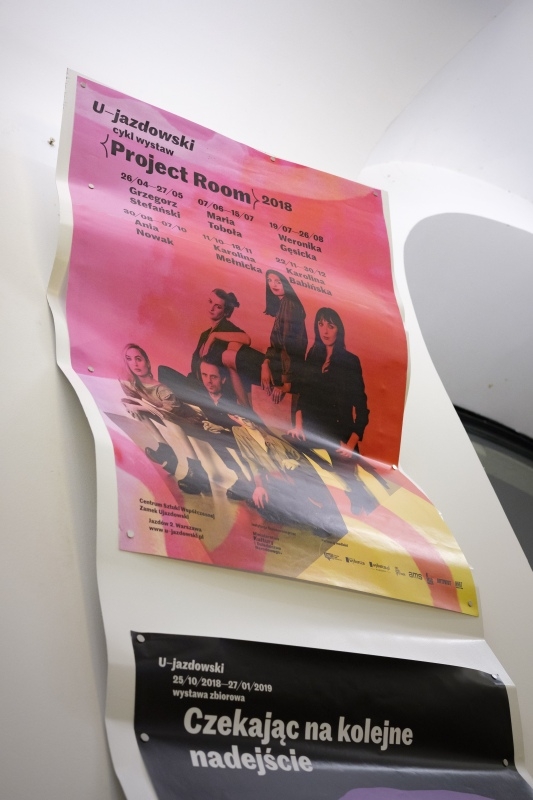

The interview was originally published in the catalogue summarizing the seventh edition of the Project Room series at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art.

Imprint

| Artist | Karolina Babińska |

| Exhibition | Do It Yourself |

| Place / venue | Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw |

| Dates | 22 November – 30 December 2018 |

| Curated by | Aurelia Nowak |

| Website | u-jazdowski.pl/en |

| Index | Aurelia Nowak Karolina Babińska Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art |