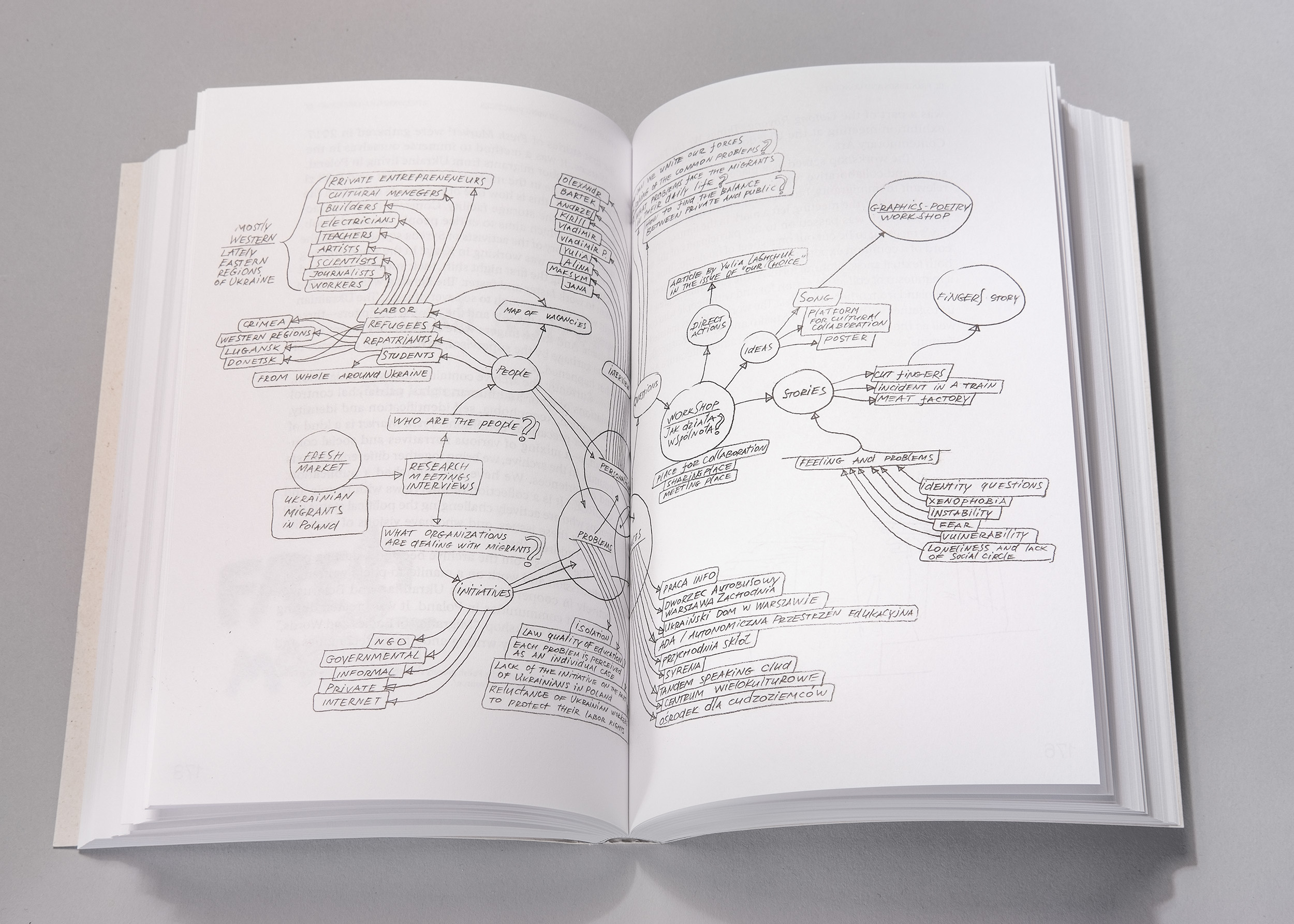

Dear Reader,

Nice to meet you. I wish to find some common ground and interests by exchanging some words and sentences on the pages of this publication. This doesn’t come naturally, as we are thinking and acting from different locations and contexts. I am from the Benelux; you are maybe from Poland with Ukrainian roots or an Indonesian living in Berlin. However, our mutual curiosity should be a good enough place to start.

In this text, I will offer some insights on how I, as an artist, understand a shared practice of citizenship.[1] This I will do starting from the Indonesian phrase gotong royong, or “mutual and reciprocal assistance.”[2] Here, I will seek to understand what it means to work together, why it matters, and what its limitations are. Understanding that perspectives are always limited, I try to encourage you as a reader to attach your own possible examples and framings. To this end, I’m proposing this text as an exercise in working together; rather than simply answering my own questions as though I had some claim to ultimate authority, I’ve delineated some blank spaces throughout where you can write in your own experiences and insights.

I have been fortunate to have participated in certain Indonesian art practices for some time now. In 2000, I was unexpectedly invited to participate in an urban printing workshop, organized by the collective ruangrupa, which took place in Jakarta, a city full of energy after the ending of the New Order regime in 1999. I’m grateful for their lessons in being hospitable and our exchange of insights into practicing art. My position as a curious outsider was easy. The effort was on their part—they unconditionally welcomed me and were willing to accept me for who I was. Initially, I was too judgmental, caring about a certain qualitative way of doing things/art, but I eventually learned to let go. Luckily, I didn’t have to undo my conditioning alone; the people I met helped me to partly overcome it.

Installation view ‘Gotong Royong. Things we do together’ at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo: Bartosz Górka

So it happened that, in 2017, I was invited by Tita Salina and Irwan Ahmett to participate in an evening conversation about gotong royong at Ujazdowski Castle CCA. As a peculiar kind of insider, I wasn’t quite sure whether or not or how I could contribute.

The term gotong royong is, for an outsider, one of many intriguing notions expressed in the Indonesian language. Other terms, such as sanggar (a model for practicing art in communal life), kerja bersama (working together), turba (going back to one’s roots), and patungan (a crowd funding of sorts) are other examples. For me, personally, they serve very well as a stimulus to test my thoughts. But in a talk at Ujazdowski Castle CCA or elsewhere in Europe, I lack a more complex and inherent understanding of these terms. Despite our lack of context, they remain useful tools to imagine a more collective art/societal production. These terms or “frame words” can provide insight into different ways of seeing art that stand in opposition to the individualized/privatized production of ideas and objects taught at art schools in the Benelux.

IN 2017, AT CCA, WE STARTED WITH THE PHRASE GOTONG ROYONG

The phrase gotong royong offered a way to get to know one another and to share insights. The basic prompt issued by this publication’s editors to inspire my contribution, however, was “continuage.” A continuage gives us the opportunity to gently move forward and find other words and understandings. In this text, I will not dive too much into gotong royong itself. Tita Salina and Irwan Ahmett are better equipped to do so. However, I want to share two sources that I used during my presentation at CCA. One is a text (or, rather, two texts) by Grace Samboh, and the other is an answer I gave to the Polish art magazine NN6T.

In Also-Class, a program I teach at the Willem de Kooning Academie, Rotterdam, I like to use Grace Samboh’s text “The democratization of knowledge and curiosity through gotong-royong art”[3] as a hypothetical exercise to make ideas on Indonesian art practices more accessible. Through the text written by Grace, I try to imagine what an engaged or “also-art” practice[4] could be like for the participants of the class. Although she doesn’t like the article any longer, it provides insights through the proposition of “gotong-royong art” as a model for re-evaluating today’s art practices.

Installation view ‘Gotong Royong. Things we do together’ at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo: Bartosz Górka

Shortly after the meeting at CCA, Grace sent me another text that explains her trouble with the previous one. Her article “Why do it together when you can do it alone,” written with David Morris, traces gotong royong to art practices after 1960. A lot of people look at the collaborative nature of Indonesian art practice as something special, as a kind of exoticism or branding almost (both inside and outside Indonesia, speaking generally). The writers question the emphasis on working together in Indonesian contemporary art, wondering whether the focus should be on other characteristics of these collaborative art practices. Isn’t “working together” more of a given rather than a special feature to be addressed as an artwork?

In my own way, I addressed this question in my answer to NN6T,[5] which asked me about the impact of art and local projects:

I think art can help to empower people/us, and if it is able to empower it can activate local urgencies. To try to solve things works only from one kind of mind-set and that is mostly not satisfying. There is no objective truth to work with. Another question arises immediately: to solve for whom, in favor of whom, to what kind of perspective? To be able to reply better to your question it could be nice to talk from a specific example. . . . What an artist brings in is not always that relevant and vice versa. Maybe it’s sometimes good to only be an assistant, a sparring partner. Another time you can take the lead in making a work or organizing an event.

In this perspective I like to look at two specific practices. Two collectives based on Java. They are Jatiwangi art Factory (JaF) and Lifepatch.

JaF is interesting because there is no real artistic program, there is mainly a citizens program and from there art is part of that. They use art as a vehicle to make situations in the village visible (and these situations are both local and global). The problem now is that JaF, because of the changing economic structure of the area, is in danger to become a formal and instrumental art space. How to overcome this or how to redefine whom your (new) neighbors are, is a challenging one. It is a compelling dilemma, which can also give us insights on how we do art here in the Netherlands (/Europe). On an extra note, although inspiring to me, there is never a really clear understanding of what JaF is or does.

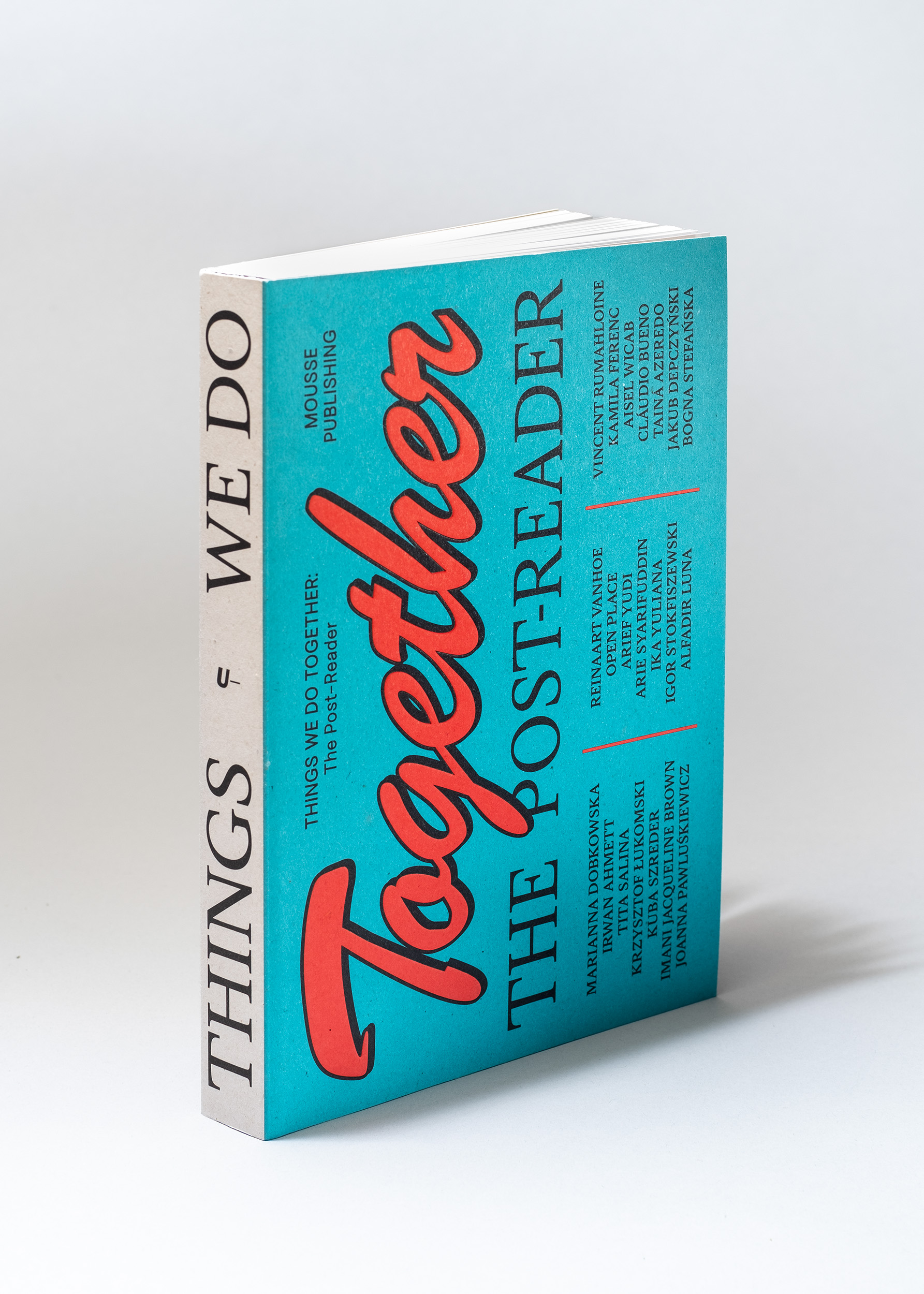

‘Things We Do Together: The Post-Reader’, edited by Marianna Dobkowska and Krzysztof Łukomski, published by Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and Mousse Publishing, 2020, photo: Bartek Górka

Lifepatch is another interesting platform for many different reasons. If I have to choose one, then it is the idea of being a collective. It is interesting to look at Lifepatch and see how individual strength is important and that being a collective is not a given situation. A collective is mostly interpreted as being one practice. But as far as I understand it, Lifepatch’s different practices (among them art practice) co-exist next to and through each other. Often we forget to look at a collective or collaborative practice as a practice of different (overlapping) activities that form a whole. Collective doesn’t specifically means doing and deciding everything together. Distributed leadership is more important than unity. Unity is not to be understood as doing one kind of program. Different practices and focuses here form a whole.

In the following sections, I will try to make these conversations more legible by describing some themes and tools.

THEMES DERIVED FROM INDONESIAN (ART) PRACTICES, AMONGST OTHERS

In the coming years, I would like to formulate a biotope[6] of what I want to call a “caring/imaginative (art) practice.” This method will probably be based on a mix of certain Southeast Asian practices. Important considerations for such a practice include how practitioners are speaking together, how to understand its social ecology, and how to understand different perspectives on how people enter into interactions.

I will focus on these three topics to look at “mutual and reciprocal assistance” as a given—as a standard way to do things for the very simple reason that we need each other for egoistic (personal development) and for sustainability (sharing energy) reasons. There is no need for an individual, self-glorifying career using critique as proof of engagement. There are no genius artists. Yes, there are bright thoughts, clear voices, revelatory moments, and visionary people, but these can be found everywhere. The challenge for me is to understand an art practice not as an independent space of production, but rather as one part of a biotope existing with other not-art-related producers. I loosely define this mode of engagement as art contributing to and being part of a social sculpture or a “caring/imaginative (art) practice.”

Installation view ‘Gotong Royong. Things we do together’ at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo: Bartosz Górka

I do very much value the role of “art” in challenging the phantasy/reality we live in, which is often taken for granted by the dominant classes and their less aware followers (such as myself). However, I want to develop a better understanding of talking and building together, and not only from an art perspective. In Indonesian art practices, popular culture is a commonly used tool for getting in touch, discovering shared interests, and starting to speak together. This “speaking together” is the first theme I’d like to touch upon here. After that, I will touch upon ecology and care, and finally I will dive into some limitations of the word “global.”

1. LEARNING TO SPEAK TOGETHER, BUILDING TOGETHER

Although “collaborative practices,” “common practices,” and “participatory practices” are very present in today’s (Western European) art discourse, there is still a lack of common language and experience to enable people to connect at a neighbor-level or street-level. These discourses are often happening within the art scene itself. The art scene lacks a network that operates outside the world of art or fails to activate it beyond its own sphere of productivity.

No one is to blame, but it’s important to acknowledge the reality. This lack of connectivity is also an issue for other kinds of practices, not least for our governments. We see governments struggling with public space, participatory programming, etc.

Here, I would like to begin the exercise of working together, or thinking together, which I mentioned in the introduction to this text. I’ll present questions and request your answers drawn from your own context:

WHAT’S THE ROLE OF CORPORATE MEDIA AND SOCIAL MEDIA—THE SO-CALLED “FREE MEDIA”—IN BEING ABLE TO SPEAK TOGETHER?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………

‘Things We Do Together: The Post-Reader’, edited by Marianna Dobkowska and Krzysztof Łukomski, published by Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and Mousse Publishing, 2020, photo: Bartek Górka

In my opinion: (Corporate) media simplifies our understanding of how we relate to our surroundings. It divides content into two contrasting sets of opinions, feeding conflict where news should not. Or, in depicting conflict, it fails to inform users about its context. Social media seems to limit perspectives of interpretation; algorithms offer a limited spectrum of information, yet this information appears to us users as neutral information. Social media limits the network of social media users much in the way that artists’ networks often only connect to people with a higher education degree. For me, this is a simple example of how we, in Western European urban life, have unlearned how to connect, unlearned how to speak together from different sides.

We can oppose and critique the world we live in, but it won’t change anything. “We lost,” as Ginggi from JaF often says. We lost against capitalist power; the only thing we can do is to share positive energy with all kinds of like-minded people and build from there. Let’s make the best out of it and support those with whom we potentially share energy, no matter what our differences might be.

The next question is:

WHAT DOES THE PRODUCTION OR CONTRIBUTION OF AN ARTIST LOOK LIKE IN A CITIZEN SCENE?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………

In answer to my own question, I’ve shared three instruments for developing an understanding of building together:

1. Change from being a consumer to understanding a consumer as a contributor:

Let’s once again become a part of what we consume. One could also think of it as becoming a “prosumer” instead of a contributor. A combination of the words “producer” and “consumer,” the term “prosumer” stems from the expectation that digital/electronic technology would make the consumer more proactive, and not only as part of a monetary relation.

How can one contribute to a spectacle instead of being a passive observer? A platform like Wikipedia can be seen as a spectacle and is a model for how to become both a contributor and a consumer. On a platform such as Wikipedia, you can give and take, contribute and learn, both with and from others. Another example is to volunteer for a few weekends a year at a vegetable farm. This simple exercise enables one to transcend the position of a passive consumer, not only for the romantic feel of it but also because natural farming is time-consuming and can never compete economically with destructive and financially speculative farming.

Installation view ‘Gotong Royong. Things we do together’ at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo: Bartosz Górka

2. Understand collective intelligence:

Together we know more; shared experience makes for better understanding. But a lot of knowledge and many experiences are not being shared or have been underrated. Cleaners

of an office building, for example, hold a lot of knowledge about how the building is used, both as workers and as users outside the parameters of their jobs. Despite this unique perspective, they will never be asked for their insights, let alone to bring their knowledge into practice. At a time when “research” is an important topic, artists are not asked to present their research before it is wrapped up as a “work.” Yet it is interesting to read together, to nurture someone else’s research, to walk together with different people so the research can truly be grounded somewhere.

3. Locate other venues and possibilities to present art:

Where and how do we share artistic production, finished or not? I have always liked exhibitions in carefully designed buildings where artworks can be approached and contemplated. Pretty floors and thoughtful details have always worked well for me. But how can we share this care, this attention for building design, with the non-professional world or the less privileged (for this situation)? These secluded spaces are often sponsored or established by “those who have.” That’s not specifically a bad thing, but the tricky thing is that this relation always starts from or enforces the perspective of the “those who have” or “those who are able to.” This circumstance must be taken seriously if we are to really share insights, experiences, and pleasures.

In her essay “Non-Western Models of Museums and Curation in Crosscultural Perspective,” Christina Kreps looks at the concepts of Lumbung (communally organized rice

barns in Java) and Haus Tambaran (traditional men’s houses in Papua New Guinea).[7] Her insights give us the opportunity to think through existing models for locating exchange, caring

for objects, and understanding “carefully made things/situations” within communal practices. After running spaces as “Kunstverein,” “Kunsthalle,” “Volkspaleis,” and “artist initiatives,” what new models can we artists imagine?

WHAT NEW MODELS CAN WE ARTISTS IMAGINE?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………

Learning to speak together is not just a fun thing; it might make people insecure about themselves. Insecurity can last for a while and is part of living. Comfort is an important element in these situations. To be able to start from a shared comfort zone and work from there (critically or not) is an important component in art for a citizen scene.

‘Things We Do Together: The Post-Reader’, edited by Marianna Dobkowska and Krzysztof Łukomski, published by Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and Mousse Publishing, 2020, photo: Bartek Górka

2. AN ECOLOGY OF A CARING/IMAGINATIVE (ART) PRACTICE

To recognize the ecology of a caring/imaginative (art) practice is to see the complex biotope of the (art) practice as an essential part of the work itself. This way of seeing can offer a renewed definition of an artwork, eliminating the need to justify either the quality or the tangible or intangible becoming of a work.

For example, how can we work around paternalism if we as artists confirm paternalism in almost everything we do? It is present in what we read, how we buy things, what we eat, how we vote, and where and how we travel. To me, there is a need to be more rooted in the concepts/ideas that we as artists are trying to visualize. I guess it can be beneficial to have a better understanding of the relation between, as artist Robbie Coleman expressed it in conversation, “the interiority of the content and the interiority of ourselves.”

Caring in this context is the nurturing of the complete “interiority” of a practice and the simple maintenance of a context you (un)willingly relate to. Some would call this relation “reciprocity,” but I mean it to be not only between people. I put my understanding of this concept of nurturing into practice by repeating the sentence, “Feed the organism.” The “feeding” can simply be done with passion, love, and with an eye for detail, almost effortlessly.

I could be misunderstood as arguing that “caring” is all artists should do. This caring is often misinterpreted as looking after (poor, vulnerable) people/species. As there is no specific good- or wrongdoing in art, there is no specific way to apply care. We could look into what the artist/work/production has nurtured and how it nurtures. In a private conversation with Gintani from Acehouse (a collective of artists in Yogyakarta) on the difference between JaF and Acehouse, she gave an example of their way of caring: “We open our space to neighboring activity as something you just do. We happen to have space to use. In our own practice we might be just focusing on our own individual practice. Or, with the model of arisan,[8] we are looking at how we can support artists and collectives.”

When talking about care as empowering so-called “less noticed speech,” I’d like to look at it as the following: Empowering happens in different constellations; empowerment is not a program. Nor is it one-directional; if all goes well, it taps into different organisms in different ways.

Installation view ‘Gotong Royong. Things we do together’ at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo: Bartosz Górka

Here’s the next question:

COULD YOU PICK AN ARTWORK/ART PRACTICE AND CONSIDER HOW IT HAS BEEN NURTURED AND HOW IT NURTURES?

(IF YOU WANT ME TO GIVE AN EXAMPLE, I WOULD PROPOSE TO LOOK INTO CONSTANT VZW OF BRUSSELS, OR TITA SALINA OF JAKARTA.)

……………………………………………………………………………………………………

It’s not only the arts that are in need of a re-evaluation. Other practices/professions are ready for the reformulation I’ve articulated. As we saw in Hong Kong (2014, 2019), or with the Gilets jaunes in France (2018), or with Barcelona en Comú (2014), the preparations for renewed practices are on their way. (I’m being positive.) Amongst others, they give spirit to provocative, bright, and constructive thought and imagination. As Isabelle Stengers writes in “Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices,” empowering is a constant state of discussion. That is what we are missing in different professions today.[9]

Although innovation, participation, and creativity are buzzwords in many professional fields, most findings, reduced to accountability, are prevented from being worked with. In other words, our future has been deliberately brought to a standstill. The book Cyberfiction: After the Future by Paul Youngquist gives us an insight into how the mechanism of economic standstill has been understood using Cyberfiction, a genre of Science Fiction that begins with S-F Magazine in the 1950s. Standstill, Youngquist describes, can be traced back to the slave trade and colonialism and forward to today’s reality of the so-called “creative industry.”[10]

But let us look into today’s reality at the street level. What would be an example to show that not only the arts are in need of a reformulation? Let us look at how roads have been built and used. A “proper” paved road is understood to be one filled with concrete or asphalt (or maybe bricks or cobblestones). Any other road is seen as a so-called backward road in a so-called backward area. But we all know that these “proper” roads don’t absorb water and that concrete retains heat over a long period of time. In March 2019, The Guardian devoted one week to an investigation of the global use of concrete.[11] In August that year, another article appeared in Time magazine, vividly describing our cities’ palaces of concrete: “If you’ve ever walked barefoot across a sunbaked parking lot, you know firsthand how concrete soaks up and retains the sun’s heat. When temperatures rise, the countless miles of concrete streets, sidewalks, walls and roofs in cities magnify that effect, creating a phenomenon known as urban heat islands.”[12]

Our societies are challenged to reconsider what a “proper” road should be. This reconsideration affects our understanding of speed, of the use of cars, and of transport in general. Transport experts could learn from “remote places” to understand pace and locate contextual solutions. There is an interest in and urgency to valuing these so-called “backward places” as much as we value the urbanized, so-called prosperous, world. With some humility, can urban societies learn from and implement rural solutions?

WHAT WOULD BE YOUR EXAMPLE OF LEARNING FROM REMOTE PLACES?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………

‘Things We Do Together: The Post-Reader’, edited by Marianna Dobkowska and Krzysztof Łukomski, published by Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and Mousse Publishing, 2020, photo: Bartek Górka

I often explain ideas from my brain, but sometimes it’s easier and more fun to just use the body. Just dancing, moving, and meeting is a simpler way of working and is often more satisfying. Artists are also keen on their ability to “move” people, to bring people somewhere in an activating understanding. In Western European institutions, artists are often used to (needed to) conceptualize and communicate subjects in a so-called proper way. Even if art projects work around unlearning or undoing, they often retain too much formalism. Does this rigid formalism stem from a fear of not being taken seriously? Do artists too often carry the problems of society on their own shoulders?

“Moving” people and oneself mostly happens informally, unexpectedly, and in between other actions. When the imperative, “We have to be aware!” is issued, most people will shy away or will merely passively confirm the message. In the arts, this means that either the audience will turn its back on you or you could be applauded for your work, remaining in an uninteresting status quo of simply pointing out critical issues from a more or less comfortable seat. It’s good to dance more, to sing together, to go out and talk, to start building things in “accessible spaces.” In their lecture at Digital Art Center (DAC) in Taipei, Taiwan, the Jakarta-based artist group Cut and Rescue performed their talk as video jockeys. This is a solid example of moving the body while leaning into popular culture and urbanity.

An ecology of a caring/imaginative (art) practice can be conceived as working with or through organisms and trying to find a way to communicate with them in totally different ways. Whether that is in words, in dance, or in spirit depends on the situation.

3. LET’S SAY, “THE NEXT DOCUMENTA[13] WILL BE SELF-ORGANIZED BY A DIVERSE GROUP OF NETWORKS”

Early in 2019, a cultural bomb was dropped. “Whaaaaaaaat,” we exclaimed, “ruangrupa—our kind of people—running documenta 15 in 2022?!” People are curious about what’s going to happen, of course. How much space for acting are these very German conditions able to grant ruangrupa? Moreover, are ruangrupa and its peers able to articulate a practice of more than twenty years in such a setting? In short, will the literal and symbolic institution of documenta, with its European perspective of organizing and doing art, hinder or amplify what ruangrupa is capable of? This kind of questioning is perhaps unnecessary, but that is part of what we people do. I would like, however, to articulate three self-critical insights about this mode of questioning.

Firstly, being a critical distant observer is a position that is as pleasant as it is cheesy. Why not join the thought process instead of questioning it? Thinking for, rather than thinking with, the other is an often-exercised practice; sometimes we can’t help it, sometimes it’s a misplaced habit.

Ruangrupa experienced the distant observer’s perspective at SONSBEEK’16, a public art event in Arnhem, The Netherlands. As curators, ruangrupa installed the ruru huis (ruangrupa’s living room)[14] as a method to relate to people and the city and to conceive of the exhibition from informal relations as opposed to institutional power-plays. They started the process one and a half years before the exhibition opened, and while things didn’t happen quite that way in the end, it at least helped them to create a partial foundation from which to relate and build.

Installation view ‘Gotong Royong. Things we do together’ at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo: Bartosz Górka

Local artists and organizers criticized the house for the good and the bad. To me (being part of the ruru huis), local artists could have seen the ruru huis as an “artist in residence” in their own city. It was a perfect chance to walk along with ruangrupa; they could enjoy or disagree with ruangrupa’s practice by experiencing it. That would mean a lot for an understanding of their own practices and positions.

Another recent remark concerning the selection of ruangrupa as curator for documenta 15—that ruangrupa is not experienced enough; that they need help from befriended European curators—is also telling. From what kind of institutional framework has this idea emerged? One can think that ruangrupa is not experienced enough, but after that thought it’s good to dive into the past activities of ruangrupa and its members. True, it is harder to do when Google, Art Forum or e-Flux is not helping out too much. The nice thing about the practice of questioning is that it helps you to move beyond your original position.

A second insight regards the location. The event documenta is not a perfect situation to work in, but when is a situation ever perfect? Maybe a perfect situation is one that is protected from the outside world and that talks only to an inner circle? There may never be a perfect situation, but one can always do something. For ruangrupa, an exhibition at a space like documenta is not the ultimate definition of their practice—it’s just one of the things they do. Documenta leads to somewhere else—it leads to some exchanges and articulations; it connects with some other unknown worlds. I suppose a healthy way of looking at it is that documenta creates opportunities on another scale. It’s interesting to see that ruangrupa is not acting as an omnipresent curator that wants everything done according to their vision. There is a balance between decision-making and letting go that shows a more humane way of organizing and practicing art in general. It doesn’t mean that you have to work less hard or under less pressure. Nor does it mean that I should idealize the way ruangrupa works.

The third and final challenge is to understand that neither an art practice from Belgium nor one from Indonesia is a given. Inviting a group like ruangrupa to curate documenta doesn’t imply their folding into the canon of contemporary art! And whose canon, anyway? The contemporary art canon is maybe something they don’t care about with all due respect. At best, ruangrupa running documenta is a step toward a paradigm shift.[15] The global (art) market gives us the impression that there is a global understanding of what “contemporary art” is, what “democracy” is, and what “world economy” is supposed to be. A limited group of people has the freedom to play with the idea of “common sense.” Meanwhile, that common sense forces a monoculture onto many others.

‘Things We Do Together: The Post-Reader’, edited by Marianna Dobkowska and Krzysztof Łukomski, published by Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and Mousse Publishing, 2020, photo: Bartek Górka

‘Things We Do Together: The Post-Reader’, edited by Marianna Dobkowska and Krzysztof Łukomski, published by Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and Mousse Publishing, 2020, photo: Bartek GórkaThere are different perspectives to be understood better. In relation to documenta, I ask myself whether there is even a need for one curator-group to run the event? Is this still how we understand the world? If indeed there is no such thing as global consensus and there are underrated understandings of organizing and doing art, then it would be nice to see these realizations in practice. That’s why I wrote, “the next documenta will be self-organized by a diverse group of networks.” It is stimulating to think of an event such as documenta where several smaller groups of people build and work from their own perspectives. I’m truly interested in an event like documenta working from a distributed network of different perspectives. Yes, I’m naïve in some aspects because I believe in distributed knowledge and power and because it hasn’t been exercised enough by myself and by my surroundings, but I wonder whether ruangrupa can lead us through this exercise.

Thanks for sharing your time; I wish you a good continuation of your day.

Greetings and thanks to the friends who have helped to generate these sentences.

Best,

reinaart

August 2019

This text first appeared in Things We Do Together: The Post-Reader, edited by Marianna Dobkowska and Krzysztof Łukomski, published by Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and Mousse Publishing, 2020.

[1] Citizenship is defined here as a tool to find common language while understanding diverse perspectives in speaking together.

[2] John R. Bowen, “On the Political Construction of Tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia,” Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 45, no. 3 (May 1986): 545–61.

[3] Grace Samboh, “The democratization of knowledge and curiosity through gotong-royong art,” in HackteriaLab 2014—Yogyakarta, ed. Adelina Luft and Grace Samboh, September 12, 2015, last accessed May 17, 2020, http://www.hackteria.org/hackterialab/hlab-14-book/.

[4] See: Reinaart Vanhoe, Also-Space, From Hot to Something Else: How Indonesian Art Initiatives Have Reinvented Networking (Eindhoven: Onomatopee, 2016). The book focuses on some Indonesian art practices, and in particular ruangrupa.

[5] Aleksandra Litorowicz, “Współpraca na korzyść. Rozmowa z Reinaartem Vanhoe,” NN6T, October 1, 2018, last accessed May 17, 2020, http://www.nn6t.pl/2018/10/01/wspolpraca-na-korzysc-rozmowa-z-reinaartem-vanhoe/.

[6] A biotope is a living place for an assemblage of plants and animals.

[7] Christina Kreps, “Non-Western Models of Museum and Curation in Crosscultural Perspective,” in A Companion to Museum Studies, ed. Sharon Macdonald (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 457–72. The use of “non-western” is indeed a tricky formulation.

[8] “Arisan is a popular community-based savings association in Indonesia. Amid various ways of saving and credit facilitated by modern banking platforms, arisan proves to be a sustaining mechanism for accumulating money.” See: Nuraini Juliastuti, “Arisan revisited: Notes on precariousness,” (Un)usual Business Journal, September 5, 2016, last accessed May 17, 2020, https://unusualbusiness.nl/en/theory/arisan-revisited-notes-precariousness/index.html.

[9] Isabelle Stengers, “Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices,” Cultural Studies Review, vol. 11, no. 1 (March 2005): 183–96. See also: Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics, trans. Robert Bononno (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

[10] Paul Youngquist, Cyberfiction: After the Future (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

[11] “Guardian concrete week,” The Guardian, February 25–March 2, 2019, last accessed May 17, 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/cities/series/guardian-concrete-week/.

[12] Vince Beiser, “Feeling the Heat? Blame Concrete,” Time, August 20, 2019, last accessed May 17, 2020, https://time.com/5655074/concrete-urban-heat/.

[13] The line refers to an e-flux project curated by Jens Hoffmans. See: Jens Hoffmans, ed., The Next Documenta Should Be Curated By An Artist (Frankfurt: Revolver—Archiv für aktuelle Kunst, 2004). Though interesting, one can question whether it really gave a new position.

[14] Ruru is short for “ruangrupa”; huis means “house” in Dutch.

[15] Firstly, it is a sign of the decentralization of contemporary art from a Western perspective. Secondly, it refers to: “This orientation towards usership, rather than bringing up yet another critique of spectatorship, is important for Wright, and for many of the projects initiated by L’Internationale, because it marks a break with modernist claims on the function of art, and also speaks to both collective practices that disrupt the institutional expectations on authorship, and the artistic constitution of environments that refuse the museal logic of collection, classification and commodification.” See: Nikos Papastergiadis, “Museums and their Spaces: From the City as Sanctuary to a Molecular Confederation,” speech during the CIMAM Annual Conference, “The Roles and Responsibilities of Museums in Civil Society,” National Gallery Singapore, November 10–12, 2017.

Imprint

| Author | Marianna Dobkowska, Krzysztof Łukomski (ed.) |

| Title | Things We Do Together: The Post-Reader |

| Publisher | Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Mousse Publishing |

| Published | 2020, Warsaw |

| Website | u-jazdowski.pl |

| Index | Krzysztof Łukomski Marianna Dobkowska Mousse Publishing reinaart vanhoe Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art |