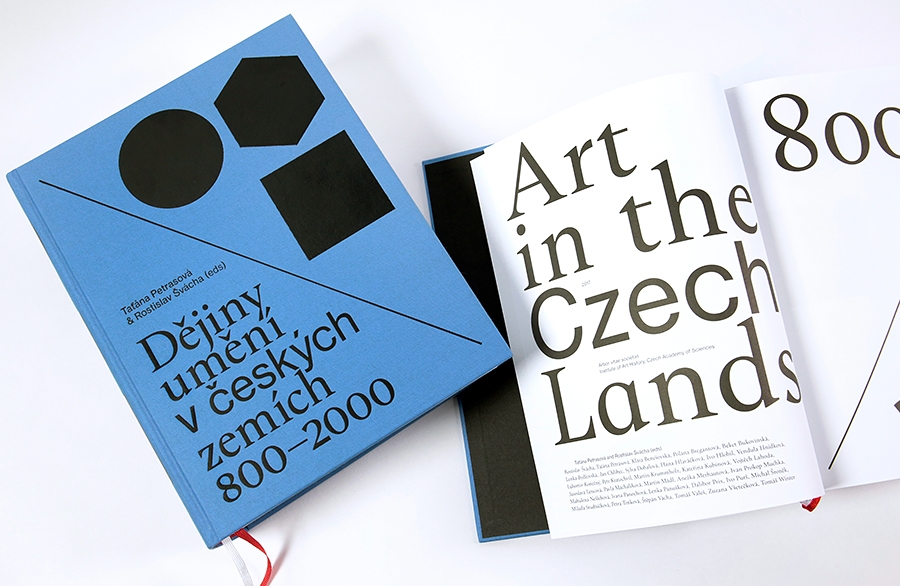

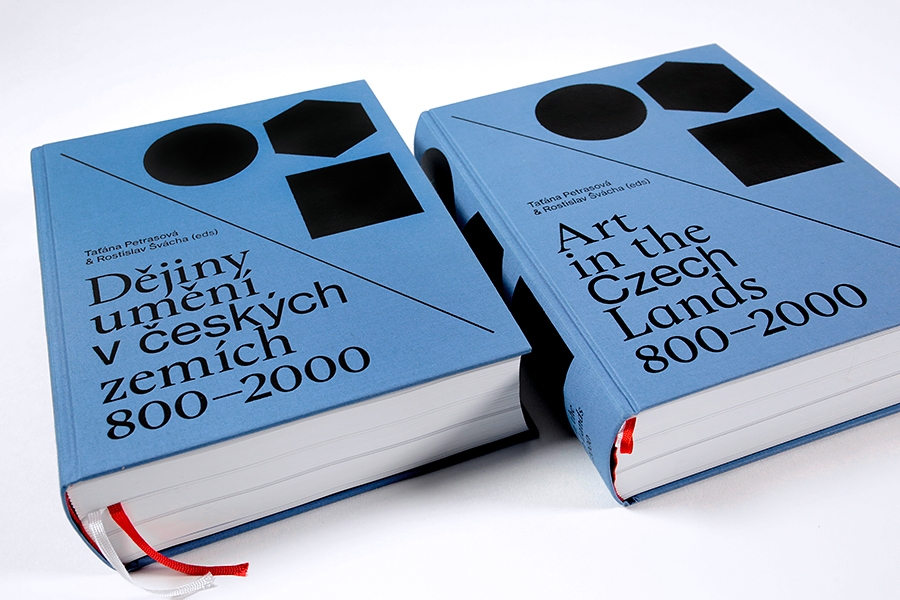

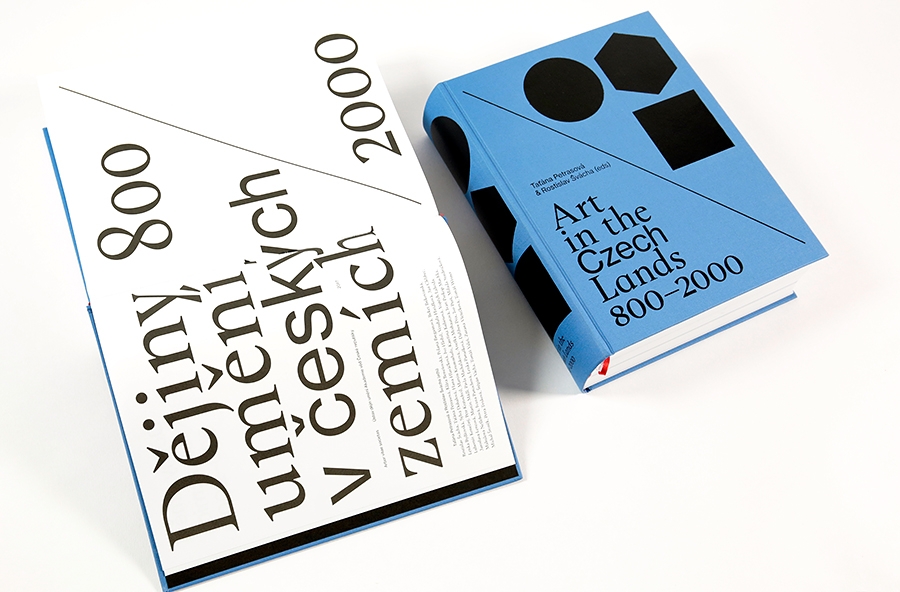

The long awaited book Art in the Czech Lands 800 – 2000 (Dějiny umění v českých zemích 800–2000) is finally available in bookshops in the Czech Republic and as an English version abroad. The aim of the synthesis of the evolution of art over more than a millennium within the Czech territory is to present the complete tableau of art in the Czech lands in a single volume accessible to the general public. And it is exactly this that seems to be the most difficult academic discipline – to generalise but without the loss of complexity and abstraction. It may also be one of the reasons why the publication has been so long in the making – in fact from the 1960s if we look at a comment on the subject by Milena Bartlová in the summer issue of art+antiques[1], who also draws attention to similar previous projects in the Czech context. Although this book is not the very first of its kind (e.g. Dějiny výtvarného umění v Československu (History of Fine Art in Czechoslovakia – 1939) by Jakub Pavel), it is clearly the most complete and most lucid finished project with the ambition of approaching the Czech history of art as a whole.

The project of art historians at the Institute of Art History of the Czech Academy of Science came into being under the editorial supervision of Taťána Petrasová and Rostislav Švácha. The content of the book, aimed at both the expert and the general public, was delimited by the editors in terms of both time and space. Rather untraditionally, the concept avoids the division into the styles of art and their respective periods. It covers three time periods (800–1500, 1500–1800 and 1800–2000) – the first part is dedicated to the Middle Ages and the second and third parts to the Modern Age, whereby each is introduced by a synthetic entry by two experts specialising in the given era, and they are followed, in chronological order, by a number of key words and highlighs of the Czech art history. The key words are numbered and preceded by the # character generally used in hypertexts – however this dimension is missing in the book. As a result the book decomposes the narrative of the history of art into a mosaic, which does not destabilise it but neither does it develop it any further internally.

While the book concept makes it clear that the authors made an effort to present the “story” of Czech art history in a more reader-friendly form than the existing so-called academic history in twelve volumes, their endeavour remained only halfway through. Although the book is addressed to the general public, I think it is too complicated to be generally accessible, while on the other hand it is not sufficiently complex for the experts. The potential target group therefore might be students of art history and related disciplines as the book provides a systematic insight into the subject and points to the relevant specialised literature.

While the book concept makes it clear that the authors made an effort to present the “story” of Czech art history in a more reader-friendly form than the existing so-called academic history in twelve volumes, their endeavour remained only halfway through.

In spite of this, I see the greatest problem, in which all the contradictions that I find in the book converge, to be the uncoordinated, unarticulated and de facto non-existent methodological framework which would define the method of creating the art-historical narrative. And it is the absence of clearly formulated points of departure that contributes to the lack of formal functionality of the whole book. Without clearly outlined foundations, the ambitious intention of the collective of 33 authors to work as a team with a clear vision and shared ideas seems to have been too idealistic. The fact that the individual texts show the strong individualities of the researchers doesn’t have to necessarily be taken negatively, if this reality had been adequatly accentuated. Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock in an introduction to their book Old Mistresses described precisely the traps and benefits of team work: “[…] Collaborative writing is an extraordinary process that requires total trust in each other. It offers a double liberation from both egoism and the anxiety associated with being alone responsible for what is said. Each partner brings different resources and abilities. Each must totally respect the other but be focused on the larger project: what is it that we are doing, why and for whom?”[2] However, sometimes the collective is so large that it attains a mass mentality, and the shared consensus is too dispersed – nobody knows from where and to where we are going, but we are all running anyway.

The English version of the book suggests it is also aimed at the foreign reader which I suppose makes it comparable with similar publications from beyond the Czech border. A comparison which is readily on hand is the concept of the book Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism and Postmodernism (2004) by a collective of four authors (Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin Buchloh, Hal Foster and Rosalind Krauss), which is divided into several periods and key words in the form of the individual years. The publication comprehensively charts the history of 20th century art whereby the target group is both the general public including students and the experts to whom it will serve well as a basic manual. But, most importantly, it is unified in its idea despite all the turbulence that the past century brought. Its authors built a methodological platform, which they described in four parts dedicated to the four most important methodological streams of the 20th century. These precede the individual thematically oriented chapters relating to selected years of the 20th century. At the same time the authors of the book Art Since 1900 succeeded in introducing elements of hypertext into the book concept, at a time when the internet was just beginning to spread more widely (at least in the Czech Republic). The different intertextual references are present in the form of marginal notes referring to further continuation of the suggested theme. As a result it is possible to read the 20th century both chronologically and anachronically by following the thread of a particular subject within the book. And it is this dimension – the presentation of history not merely as a sum of facts but rather as a kind of hyperobject – that I expected when I was opening the pages of Art in the Czech Lands 800–2000 for the first time and was browsing through the individual keywords. Unfortunately, in this case they are just blind alleys filled with information and accompanied only by standard references to further reading. At this point I don’t think the Czech history of art would be any poorer in terms of its intertextual potential than the construct of international history. Quite the contrary, compared to the particular canon of the world history of art it can provide richer and multilayered material in many respects.

Although the introductory text by Rostislav Švácha mentions the “changing borders” as a typical feature of Central Europe, the whole concept of the publication corresponds with the contemporary arrangement.

The missing or at least very vague and not unified methodological point of departure of the new publication has an impact both on the terminology and the interpretation of the chef-d’œuvres. The problems with methodology start with a priori premises regarding the understanding of time and space. The temporal boundaries of the book are delimited by Great Moravia at one end and by the turn of the millennium at the other end, while the spatial demarcation is identical with the present day territory of the Czech Republic[3]. The linear temporality of the book may be worn out a little but is not an issue in itself given that the book is intended for the general public. However the focus on art production within the contemporary boundaries of the Czech lands, but in a historical perspective is quite problematic.

Although the introductory text by Rostislav Švácha mentions the “changing borders” as a typical feature of Central Europe, the whole concept of the publication corresponds with the contemporary arrangement[4]. The declared dynamism of the territory may always be noted, but it is not worked through to its full consequences as this would require abandoning the book’s territorial demarcation. While the authors disagree with nationalist motivation in the making of history, they avoid the vexed question about what in fact constitutes “Czech art” (the relevant reflection is dispersed throughout the book in subsections by different authors[5]) and simultaneously they make the reader accept something of a canon of Czech art, regardless of the historical instability of the territorial arrangement and the ensuing requirement for a variable perspective, when the talk is about what and at which time it can be given the attribute Czech. Regardless of what we may think, the space has a dynamic of its own, in spite of the fact that it can be quantified. As Peter Burke showed in his text Did Europe Exist before 1700?,[6] being European is not defined by the continent but it is construed on the basis of spatial dynamics. Analogically, we might start to think about what the attribute Czech actually means, when the history of the Czech lands should perhaps be described as nomadology, as proposed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari – not the static history of a single small territory, but a changeful territory which can be related to from multiple points of view.[7] This means that what is Czech is shaped by those who pass through the territory. In this way the notion of “Czech lands” is a heterogeneous, discursive space with no fixed boundaries.[8]

If we continue to consider history to be a sum of facts of which some have greater and some smaller imaginary weight, and based on this imagine it as solidified time, we will never liberate ourselves from the dogma of the canon which has often been questioned and refuted.

The territorial demarcation is the most problematic in the introductory synthetic chapters, where it is slightly balanced out by the individual profiles in which the criterion of the boundaries is not so strictly observed (sometimes this is even impossible). It might be the reason why the authors of the different synthetic texts often use non-unified and rather arguable terminology as a designation of today’s territory of the Czech Republic – here I consider the term Czech state to be the most controversial. According to the book, the period when “the Czech state was born, consolidated, and strengthened,” is the Middle Ages[9]. In the course of the Middle Ages Czech territory dynamically expanded, reaching a peak during the reign of Charles IV, when it extended almost as far as the Baltic Sea. It is therefore questionable whether we should consider only a fragment of it, which is Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, when artistic exchange took place all over the territory, not to mention its ethnic diversity. Related to this is the anachronic application of the term “state” as early as in the first period under observation. A “state” is a political organisation with a central government which has a monopoly on administration within the given territory. This description may be related to the Renaissance Italian city states (Niccolò Macchiavelli defined the term state for the first time in The Prince in 1532), but in the context of Central Europe it is probably not possible to use this term to characterise a territory before the Modern Age in relation to Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651). This subject is approached very sensitively in the last synthetic text by Taťána Petrasová and Vojtěch Lahoda – but strangely the territorial point of view is strictly observed even here, so that we only learn about the Czech-Slovak polarity in the 20th century from key word #232 titled Slovak Artists in the Czechoslovak Republic.[10] On the other hand, a step forward is the attention paid to Czech-German artists in former Czechoslovakia[11] or, to be precise, in Bohemia and Moravia. However, to accept the premise of a dynamic territory means also to adopt dynamic temporality which, I think, would again result in a considerable review of what can be described as Czech and hence questioning and maybe even deconstruction of (the construct of) Czech history of art.

This book was born in the form expected in the Czech milieu from as early as the 1960s, although its concept was updated following the intellectual freedom brought by the 1990s and contemporary research in the field of art history. As such it represents something of a canon within the boundaries of the Czech Republic which generates more problems as it progresses towards the present when the individual key words seem almost random (e.g. #260 New Media: Generatrix[12]) and where institutions which do not fall within the delimited time frame are referenced outside the concept (see #257 Private Collectors After 1945[13]) possibly suggesting a (probably unintentional) conflict of interest on the part of the relevant authors and institutions.

If we continue to consider history to be a sum of facts of which some have greater and some smaller imaginary weight, and based on this imagine it as solidified time, we will never liberate ourselves from the dogma of the canon which has often been questioned and refuted. I believe that history is a dynamic hyperobject where the only certainty is change. “When we scan things for traces of the shape of the past, everything about them deserves our attention.” Given the arguable concept of the publication project in hand this quote by George Kubler, which can be found at the end of his book, becomes an empty cliché. Kubler stood at the beginning of discussion of heterogeneous time and space in the methodology of art history,[14] but here his work seems to be mentioned purely expediently. In the end this unreflective appropriation of the ideas of this art historian who actually defied the concept of the canon illustrates well the methodological indecisiveness and inner contradictions of this extensive publication that we have awaited for so long.

The review was originally published in Artalk

[1] Milena Bartlová, Poznámky k (dějinám) umění: Čekání na dějiny (Notes on (the History of) Art:Waiting for History), in: Art & Antiques, No. 7-8, 2018, p. 2.

[2] Roszika Parker – Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology, New York 1981, pp. xxiv-xxv.

[3] Taťána Petrasová – Rostislav Švácha (eds.), Art in the Czech Lands 800-2000, Praha 2018, p. 33.

[4] Ibidem, p. 33.

[5] Ibidem, pp. 34, 48, 343, 352, 618.

[6] Peter Burke, Did Europe Exist before 1700?, in: History of European Ideas, vol. 1., 1980, pp. 21-29.

[7] Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Minneapolis 2005, p. 23.

[8] Michel Foucault, Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, in: Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, no. 5, 1984, pp. 46–49.

[9] Taťána Petrasová – Rostislav Švácha (eds.), Art in the Czech Lands 800-2000, Praha 2018, p. 39.

[10] Ibidem, pp. 830-833.

[11] Ibidem, pp. 803-804.

[12] Ibidem, pp. 924.

[13] Ibidem, pp. 912-913.

[14] George Kubler, The Shape of Time, New Haven 1963.

Imprint

| Title | Art in the Czech Lands 800 – 2000 |

| Publisher | Arbor vitae societas, Artefactum |

| Published | Prague 2018 |

| Website | www.arborvitae.cz |

| Index | Arbor vitae societas Eva Skopalová Felix Guattari George Kubler Gilles Deleuze Griselda Pollock Michel Foucault Milena Bartlová Peter Burke Rostislav Švácha Roszika Parker Taťána Petrasová |