This is a queer exhibition. Not in the sense that it is about queer sexual or gender identities or desire, but because in its thematic facet it critically touches upon everything which tends to create stable, all-encompassing and therefore always oppressive norms and binaries. Queer is a space, a mood, a drive enabling the opening up towards something significantly new. And today’s world needs transgression from the growing level of inequality and injustice to significantly new space. The centenary of women’s emancipatory work in Poland, since they obtained the rights for voting (1918-2018), is a centenary which mirrors the people’s struggle to get rid of many injustices arising from gender inequality, or perhaps to get rid of gender in general. The exhibition 100 Years, So What? invites to think about the abovementioned issues through the works of seven artists of Polish origin – Małgorzata Dawidek-Gryglicka, Dorota Hadrian, Iwona Demko, Katarzyna Perlak, Zofia Krawiec, Alicja Rogalska and SIKSA. All the artists of 100 Years, So What? challenge the centuries of binary constructions of femininity, reclaiming the right to be beautiful away from sexist and objectifying glances, reclaiming the space of work and study, reclaiming the right of self-love without accusation of narcissism and of flirting with patriarchy.

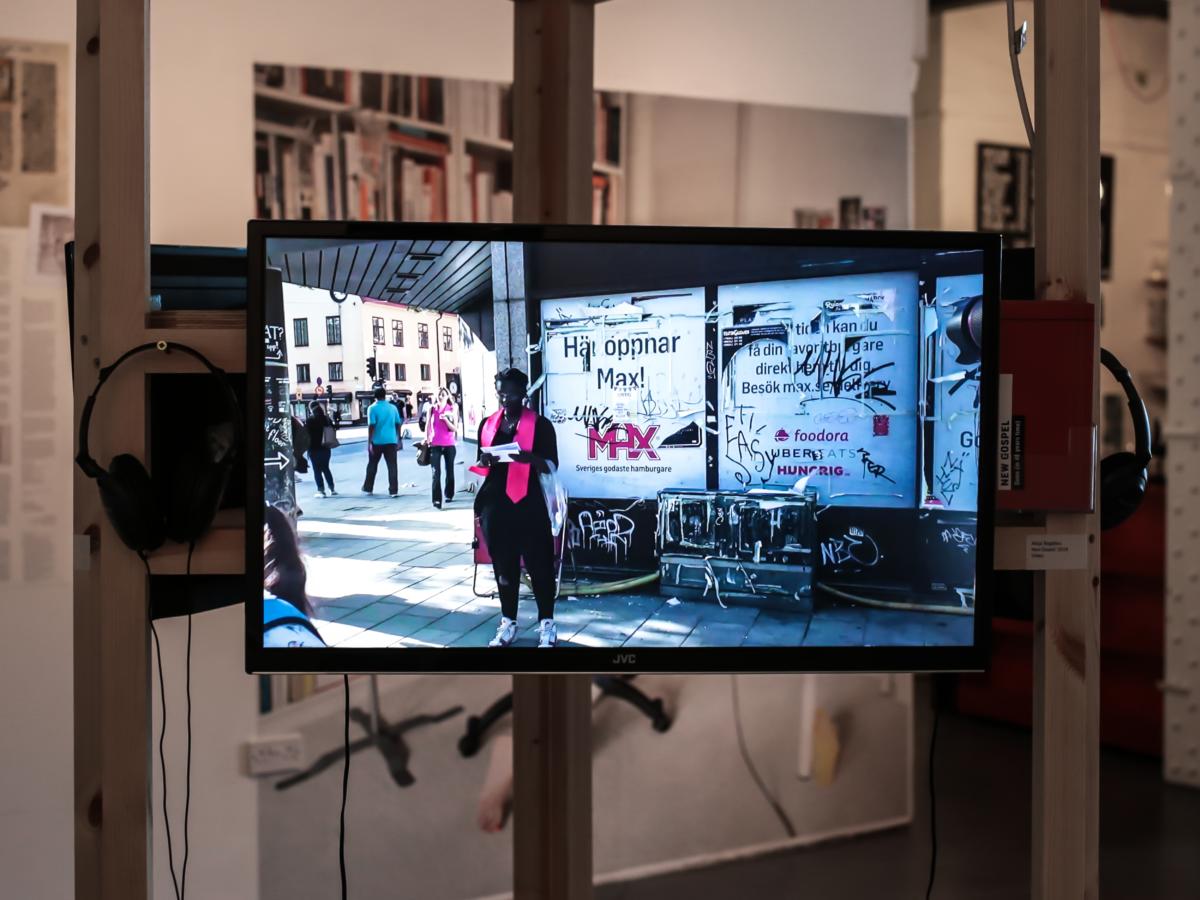

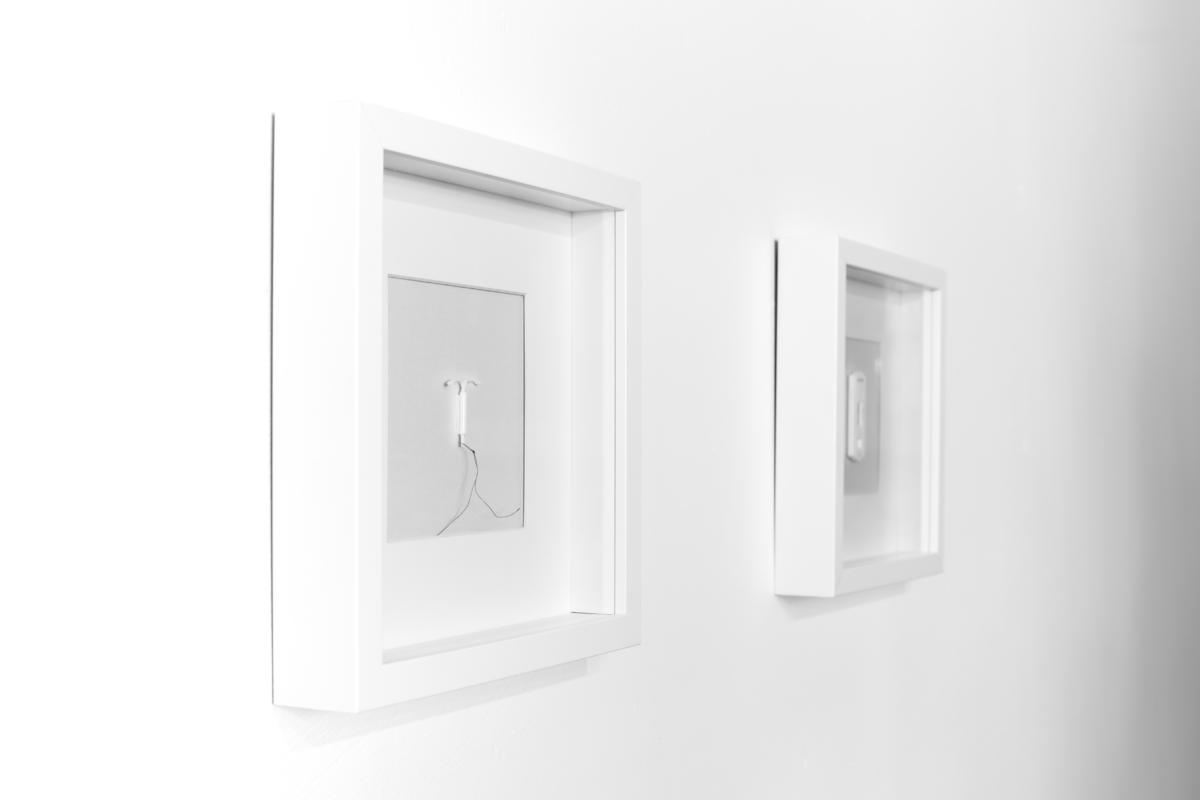

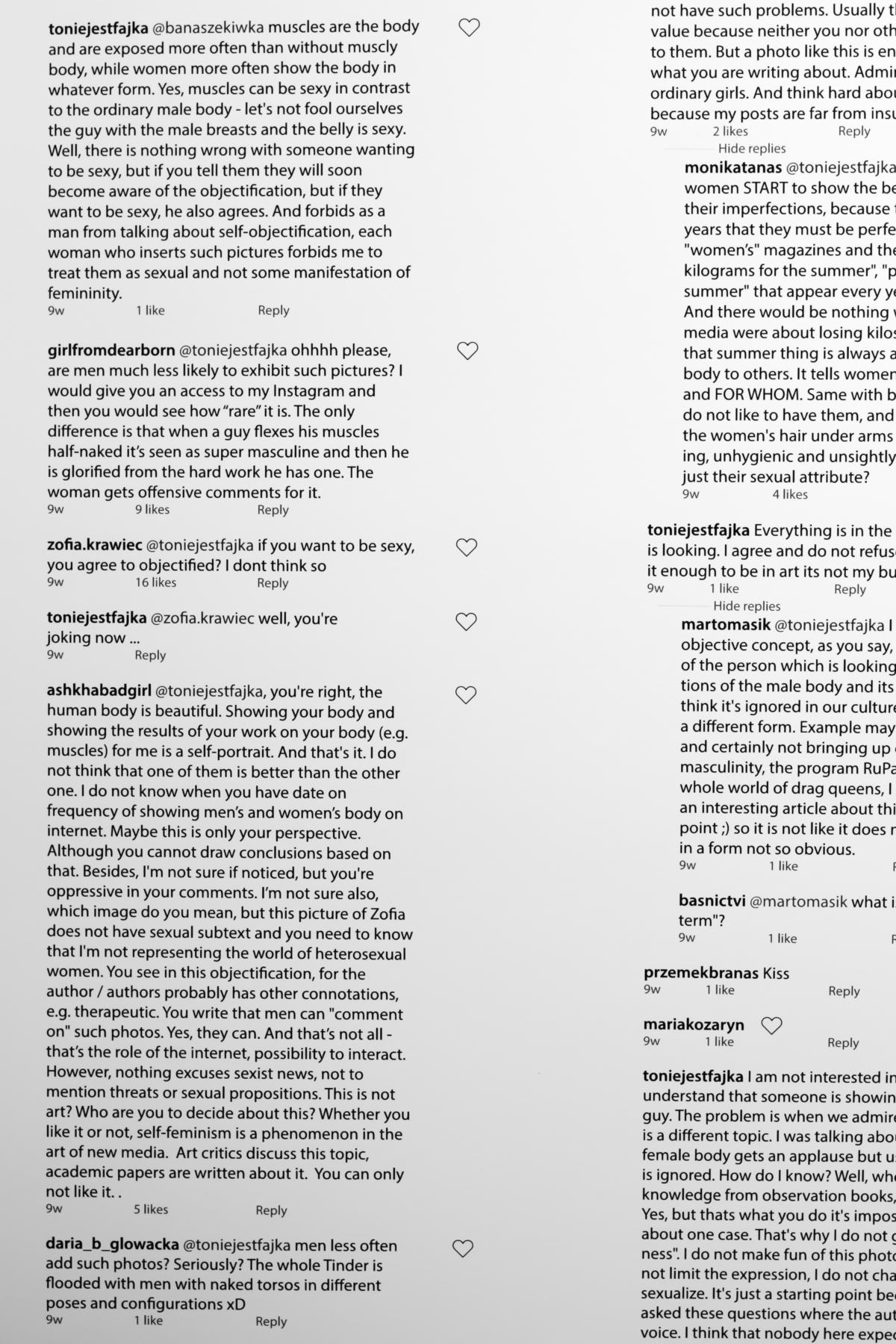

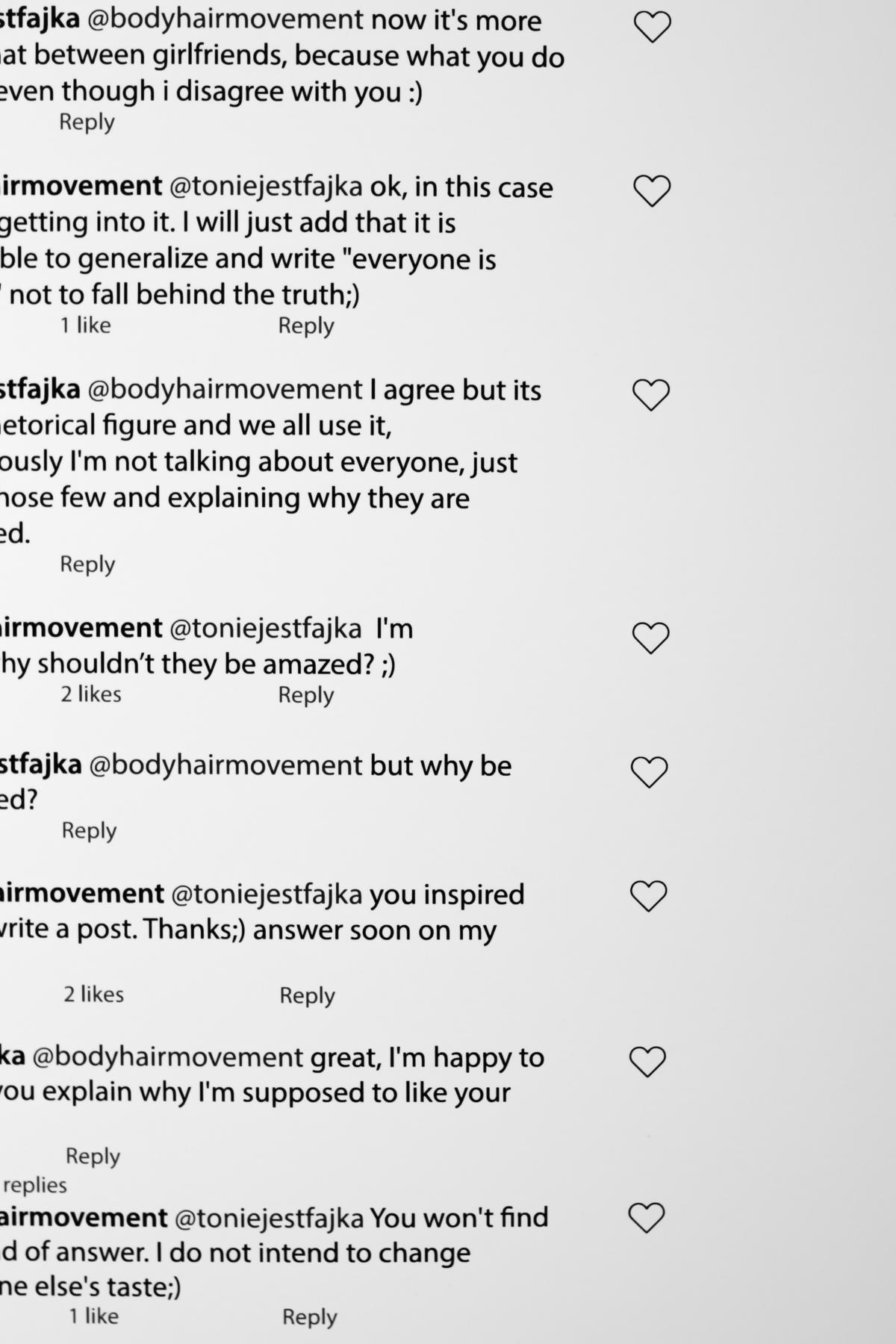

Małgorzata Dawidek-Gryglicka plays with the conventional attribute of femininity, a mirror, in her work Marcia and Malgosha Creating Their Self-Portraits Using Mirrors (2017), which features a copy of Marcia Painting Her Self-Portrait Using a Mirror from Giovanni Boccaccio’s manuscript On Famous Women (De Claris Mulieribus, circa 1404) and photography of the artist, here Malgosha, “Creating Her Self-Portrait Using Mirror”. The project is part of Dawidek-Gryglicka’s research on cultural memory of first female writers and artists and HerStories. The artist chooses the mirror, usually an attribute of desire for conventional beauty, as seen through women’s work and engagement in the world, because what is reflected in the mirror is both the subject and the object of artistic activity, creating a powerful message of self-importance and relevance, away from themes most often connected with women, such as domesticity, children, flowers, garden, replacing them with work, among books. Yet, the themes of the motherhood and domestic duties, through which femininity is traditionally defined are used as a background for Dorota Hadrian’s video Saturn (2016). The title of the movie refers to the Roman god Saturn, who ate his own children out of fear that one of them may take away his throne. Saturn was the god of periodic renewal. He was the legendary ruler of Italy, considered to be a teacher of agriculture and grapevine as well as synonymous with masculine power, patriarchal order, in which men possess symbolic authority. The film aims to present an inverted order; a new mythical beginning: new Saturn. Hadrian also stresses that on one hand the video is her personal footnote to the overwhelming role of motherhood in Polish culture, embodied in the symbolic construction of Mother the Pole, and on the other it is an illustration to many philosophical works aimed at deconstruction of the patriarchal position of women. In this way it is a tribute to the feminist scholarship. In a direct dialogue with Saturn is Iwona Demko’s work Maleusiophobia, or Fear of Pregnancy (2015-2018), which openly ‘shouts’ that not every woman wants or needs to be a mother. Iwona Demko, presenting a photographic series attributes of pregnancy, which are treated here as sort of socially fabricated symbol of ‘female ecstasy’. Yet, title of the series created the distance to the subject matter denoting the psychological disorder, neurotic condition, which is a fear of pregnancy, maleusiophobia. Other neuroses created by culture, this time by the standards of beauty, are presented with an ironic twist in Zofia Krawiec’s Neurotic Girl (2017). This artist presents a selfie, an Instagram photo, a self-portrait with the decorating shadow effects reflecting on the naked body. Neurotic Girl depicts a perfectly beautiful body with the illusion of decorations, yet the woman is still sad in the photo, either neurotically not too happy with herself, or she provocatively asks about the importance of normative beauty, hence accusing as the viewers of a neurosis or as we might call it – the beauty fixation. The photo invites us to ask questions, both a bit mocking: is the woman so neurotically pretty, or it is us, the viewers, society, who are pretty neurotic? The appropriation of normative beauty and playing with its canons for the feminist messages can, of course, sounds like an entanglement with sexist and patriarchal norms, yet, it can also be a gesture of reclaiming the independent voice. Games being played with the “girlish girl” stereotype can also be seen also in the works of Katarzyna Perlak, a multi-media artist of Polish origins, based in London for the past 13 years. In her work Self-Portrait with Strawberries (2016) and Baby You Deserve (2017) she presents the provocative central figure, an attractive woman with long, pink hair siting on a chair and smoking, confrontationally looking directly at the viewer and creating a challenging interaction. Yet, the background and the sound of seashore create a sense of inaccessibility to the central figure. The song that accompanies the video intensifies the effect of cumulated stereotype: overdressed woman, provocatively sitting and waiting and puzzling everybody simultaneously: a parent, the potential lover, viewer, whoever desires to put her in their world and their order. Yet, she always escapes. Like Dawidek-Gryglicka in her historical references to other artworks, Alicja Rogalska’s New Gospel (2018) also enters a historical dialogue, this time with the politician and activist Alexandra Kollotai, a Russian revolutionary with a strong feminist agenda. New Gospel was created in Stockholm, in May, and it is a video documenting a radical feminist manifesto inspired by Alexandra Kollontai’s writings and contemporary feminist theories delivered by performers – missionaries, spreading the news of a new kind of society to unassuming passers by in Stockholm, Sweden. The performers play the role of street preachers, but instead of proselytizing the coming of Christ or the end of the world they preach a post-gender, post-work and truly egalitarian society.

What Rogalska suggests is that we need a new kind of oration, new kinds of prophets, those who will take contemporary femininity away from traditional binary systems, from consumerist tyranny, home, motherhood and family expectations, all stereotypes and myths so dangerous and unfair for both sexes, to all genders. And the Polish punk performers SIKSA presents new form of preacher in their video, Revenge on the Enemy (23.09.2017) SIKSA, the perfo-punk reminds us why we wanted to grow up when we were small, and once we are adults, we think we want to go back to being kids. Through her provocative, theatrical concert/performances she challenges our expectations about who we are as the members of family, society, how we judge and are judged by others, which usually is a violent act. SIKSA tries in a very emotional way to tell herstory of physical and verbal violence, which she treats as therapy, both for her and the viewer. 100 Years, So What? not only presents Revenge on the Enemy as an installation, but also invites to see SIKSA live during the finisage of the exhibition on the 19th of July.

Hundred years of women’s emancipation, how much has changed? We don’t deny that much has… however, hundreds of thousands of women have been out on Polish streets in recent years to fight for the basic rights to have an abortion, therefore we include the sceptical “so what?” in the title… But the exhibition is far from being pessimistic. Provoking? Perhaps, and a bit angry too, and this is why we utilise the word “queer” here for contemporary avant-garde women’s art as the channel towards a radical redefinition of the position of women in politics, society, family, or history, creating powerful, queer herstories.

Urszula (Ula) Chowaniec

Imprint

| Artist | Małgorzata Dawidek-Gryglicka, Dorota Hadrian, Iwona Demko, Katarzyna Perlak, Zofia Krawiec, Alicja Rogalska, SIKSA |

| Exhibition | 100 Years, So What? Young Polish Multimedia Artists on the Centenary of the Establishment Women’s Voting Rights |

| Place / venue | Centrala Gallery, Birmingham |

| Dates | 13 June – 28 July 2018 |

| Curated by | Urszula Chowaniec |

| Photos | Handover Agency |

| Website | centrala-space.org.uk |

| Index | Alicja Rogalska Dorota Hadrian Iwona Demko Katarzyna Perlak Małgorzata Dawidek-Gryglicka SIKSA Urszula Chowaniec Zofia Krawiec |