The following series of questions developed by artist and activist Imani Jacqueline Brown, are based on a series of “Kaleidoscope Conversations” she organized at the Ujazdowski Castle Center for Contemporary Art in late 2017. The format of the art project invited participants and gallery-goers to consider developing a dialogue around critical issues through questions only. According to Brown, “One question renders into another, then another; the questions weave together into a meditative conversation that foregrounds the courage to explore the unknown together, rather than our tendency to wield knowledge and the truths we hold dear as weapons.” The questions below have been recorded and transcribed from her project, presented and interspersed with some of her thoughts and images from from Warsaw in the fall of 2017.

It’s the final week of the 2017 and as with every year we remain standing with our backs to the horizon, gazing over the shitstorm of the past year as it rages on against the distant mountains. Our year-end habit is to take stock, to catalogue the best and the worst. But rather than summarize the past, I’d like to offer up something for the future.

In 2018, we will embark on our seventeenth year within the expansive desert of time still known as the “Post-9/11 Era”–a time marked by ever-escalating dog-whistle Islamophobia, ever-expanding foreign proxy wars, and the steady erosion of civil liberties––and it seems we have finally begun to acknowledge that we are lost. As terrifying as it has been, I believe that 2017 was special and significant. This was the year that saw the dawn of the presidency of Donald Trump and, finally, the return of the word “fascism” to the lips and lexicons of mainstream American political pundits, as well as recognition of the fecundity of this phenomenon in American soil. In the waning light of an American Century catalyzed by the dropping of the Atom Bomb, our political influence radiating far and wide can no longer mask as exceptional as evidenced by the Polish right wing’s affinity with Donald Trump and its bid to secure pan-European unity through entry into the exclusive club of whiteness. Is mainstream America at the cusp of recognizing and eventually rectifying the fundamental fascisms at the core of our civilization? Or will our country’s unprecedented bipolarization devolve into a Civil War that will doubtless have ramifications for the entire world?

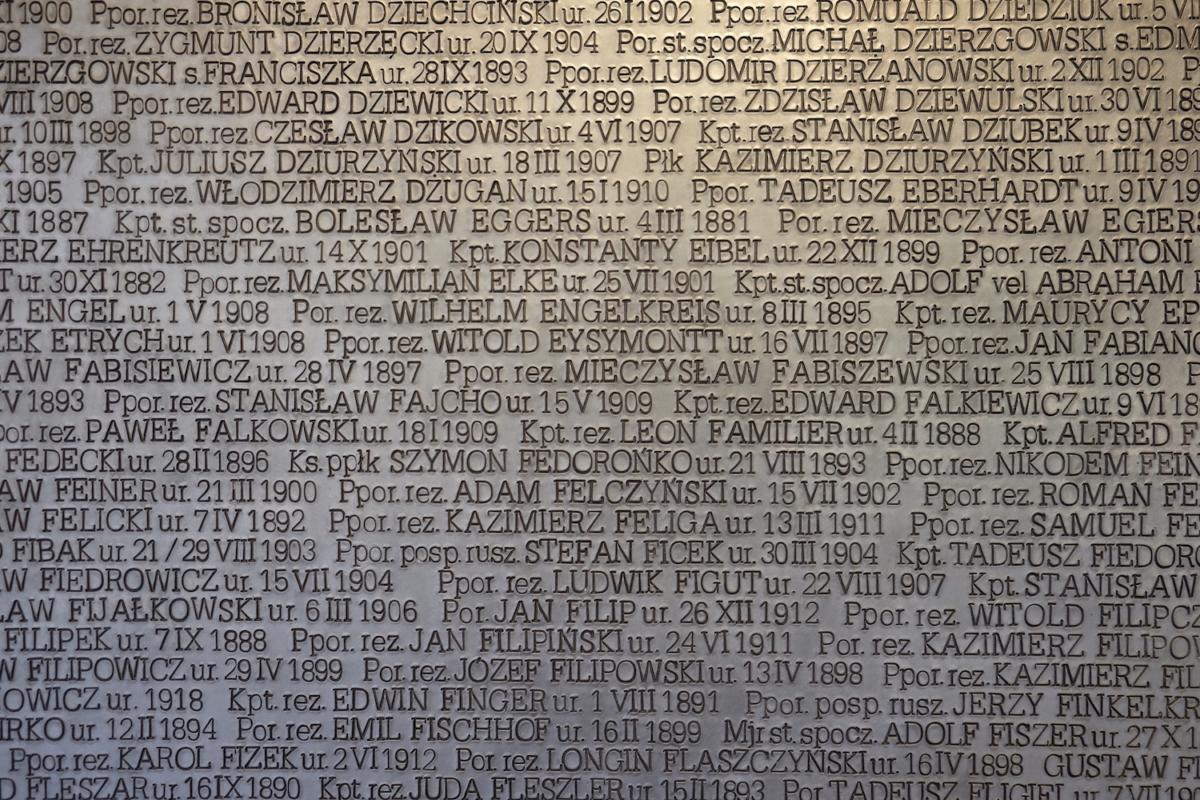

I travelled to Warsaw, Poland, in November for a month-long residency at the Ujazdowski Center for Contemporary Art to participate in an exhibition and public program called Gotong Royong, an Indonesian phrase denoting mutual aid and commonly translated as “things we do together”. I wanted to use my time to explore exactly who “we” are, what exactly we propose to “do”, and what we mean by “together” because in 2017 it seems as though we have never been so divided. Through my project, called Truth as Theatrical Fiction, I posited that fascism is merely a signal of an underlying condition: the atrophy of the inquisitive faculties of individuals and of society-at-large triggered by our inability or refusal to question our foundational personal truths, our assumptions about the unknown, our societal myths, our family prejudices, our pedagogical lapses, and our leaders’ agendas. If true, how might the practice of asking questions build depth and clarity into our worldviews? If we expect those on “the other side” to check themselves, we on the left must first become experts at doing so. And, surely, there are many questions that we must ask ourselves. After all, if we had all the answers, we would be winning.

The central component of this project was a series of “kaleidoscope conversations”. For one hour per week for four weeks, a group of individuals on the “left”––artists, art administrators, art public, activists, students, and professors from Brazil, Canada, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, Poland, and the United States––explored a mode of dialogue that gives space for questions but not answers. One question renders into another, then another; the questions weave together into a meditative conversation that foregrounds the courage to explore the unknown together rather than our tendency to wield knowledge and the truths we hold dear as weapons. Eventually, I will record and map these questions, documenting surges, convergences, shifts, and voids in our thought processes. But for now, here are ten kaleidoscopic questions (and ten sub-questions to further question those questions) that might be helpful as we attempt to navigate the inevitably complex, contradictory, and conflicting waters of 2018:

- What is fascism?

- Who are “they”?

-

- What is the difference between patriotism, nationalism, and fascism and how are the borderlands between one ideology and the next maintained?

- What is the difference between “offensive” and “violent” discourse?

- If we incorrectly lump those on the far right into the category of “fascist” or “Neo-Nazi”, have we bolstered the visibility of those who are actual “fascists”?

- If one’s environment is fascist and all of one’s family is fascist, what conditions need to exist in order to thwart the rise of fascism in oneself?

- Are fascist characteristics a result of nature or nurture?

- Do fascists fantasize about the “other”?

- If we call people fascists or Neo-Nazis, do they lose their humanity and become monsters?

- Should we attempt to isolate fascist ideology away from society, treating it as a plague, or should we examine it under controlled settings as a cancer?

- Do all fascists have the same visions, values and goals?

- If we know divide and conquer is the best strategy, why don’t we divide the fascists into their constituent parts?

- Why don’t we recognize that there are some victories that we share and celebrate those moments together?

-

- Is segregation between sides of society inevitable?

- What is the role of the media in maintaining the division between these two sides?

- How can we invite the other side to engage in dialogue so they have an opportunity to listen to us and we to them?

- Could dialogue even get us anywhere with people whose minds are shuttered by hate?

- Shouldn’t they feel unwelcome and excluded from polite society?

- Shouldn’t we defend our safe spaces from intrusion by those on “the other side”?

- What if they were to come with weapons?

- Might you be willing to march alongside a nationalist or a fascist in an attempt to gain something that you find valuable politically?

- What are the values that people on the left and the right share and how can we point to them to address the problems currently facing humanity as a whole?

- Why was the left unable to celebrate the failure of the Trans-Pacific Partnership––a long-standing leftist goal––once it was clear that the victory would be achieved by Donald Trump?

- Can the nation-state exist without nationalism?

-

- How are we preparing for the fact that the future is unstable and likely migratory and what kinds of global citizenship can we design to prepare for this future?

- If we don’t have national borders, how will we ensure that we have enough for our families?

- Do we consider our national identities to be an important element of who we are as individuals?

- Are all nations’ nationalisms––Polish, American, Brazilian, Indigenous, and Palestinian, to name a few––created equal?

- If we think that nationalism is so problematic, would we be willing to live without a nation as and in solidarity with stateless persons?

- Is it time to bring back the city-state model?

- Isn’t it elitist to consider travel as essential for the holistic development of the contemporary person?

- Wouldn’t it be better if we resisted the push toward urbanization and cosmopolitanism and just stayed home to do deep work within our local communities?

- What if we can’t go home because our homes have been bombed?

- If “European values” are our tool for expanding ideology beyond national borders, don’t we need to examine the process through which “European values” gave rise to imperialism, colonialism, capitalism, racism, and nationalism?

- Is fascism baked into the foundations of Western Civilization?

-

- If so, is it possible to uproot fascism without destroying the foundation?

- Should we destroy the foundation?

- Is fascism the natural bookend to the rise of capitalism, imperialism, colonialism, and the nation-state in the 16th and 17th centuries?

- Is the resurgence of fascism and populism a result of the failure of the left to present a desirable, functional and beautiful alternative to capitalism?

- What is the relationship between nationalism and inheritance?

- If patriotism is connected to patriarchy, can fascism exist in a matriarchal society?

- Is fascism the response to a perception of a new clash of civilizations between Christianity and Islam?

- Why haven’t we foreseen the symptoms for something that is clearly a repetitive mechanism?

- If fear leads to fascism, is the repetitive nature of human violence legible through the lens of genetic trauma?

- Is the rise of fascism as natural to social cycles as death is to life––a societal wave break that arrives just as we begin to settle too comfortably in affirming the truth of teleology?

- If we recognize that truth is a fiction, what then happens to history?

-

- Are we speaking the same language as people whom we define as fascists?

- Are we speaking the same language as the people on “our side”?

- What is the difference between “personal”/”emotional” truth and fact?

- How do we know that our truth is the real truth?

- Will a multiplicity of truths always erupt into chaos?

- How can we honor our respective truths and hold them in balance without losing our sense of values and morality?

- If there are always as many truths as there are individuals, how can there only be two sides?

- What is the historical origin of the division of the political spectrum into right and left?

- Does the left or the right still exist?

- Did they ever truly exist?

- Is it righteous to punch a Nazi?

-

- More importantly, does punching a Nazi help us to achieve anything other than a personal sense of satisfaction?

- If we derive satisfaction from exerting violence on Nazis, does that inch us closer to fascist behavior?

- Isn’t it important to send them a message that we will always fight back?

- Shouldn’t we feel good about fighting Nazis?

- What is the moral and psychological meaning of resistance?

- Is it possible to fight for peace?

- Has any society ever defeated fascism without the use of violence?

- Is there a difference between a system that uses violence as a means to an end and one that sees violence as an end in itself?

- Can we differentiate correctly between pain and pleasure?

- So what, are we going to fight guns with art?

- How can we create an alternative to fascism through our own actions in everyday life?

-

- Is it possible to celebrate history without performing violence against another?

- How can we articulate anti-fascist visions so that they are actually accessible to and understood by people?

- What is the connection between protest and real transformation of society? Is going to anti-fascist demonstrations actually “fighting fascism”?

- Is the rise of fascism connected to the loss of public space and the atrophy of public debate?

- What public spaces might be available for commiseration between the two sides?

- Is it important for cultural institutions like art museums to be safe havens for the incubation and exploration of left-wing ideas or is there genuine potential for art centers to serve as open spaces for the exploration of different mindsets?

- We are opening public spaces within our cultural institutions; why is the public still not coming?

- If a manifestation an act of promoting something in a positive way rather than protesting against something, shouldn’t we use our public actions to promote what we are for rather than what we are against?

- If there were more opportunities for joyous public festivity, would nationalist spectacles lose some of their appeal?

- Can we actually imagine this revolution we are longing for so much?

How will we remember this year? Personally, I will remember 2017 as the year when I first realized that I am no longer so certain about what I know, when I realized that I needed to start asking what I don’t know. In 2017, I picked up a practice of asking more questions than ever before, but I still don’t have answers. Is it too early to have any answers? Is it too late? As uncertain as it all seems, we can at least be grateful for the clarity that 2017 has brought in defining the edges of fascism’s long shadows. 2018 is a year of local elections, and with parties like Razem in Poland and the Democratic Socialists in the US attempting to reach across the political void, this is doubtlessly the year to being asking deep, probing questions about how we came to be in this schizophrenic political moment and where we must go from here.

Imani Jacqueline Brown is an artist, activist, and researcher; she is a co-founder of Blights Out and a core member of Occupy Museums. In 2013, Imani took part in Winter Holiday Camp, the democratic takeover of the Ujazdowski Center for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, Poland, in support of a union labor strike against the former director; she returned to Warsaw in 2017 for a residency at the CCA as part of Gotong Royong.