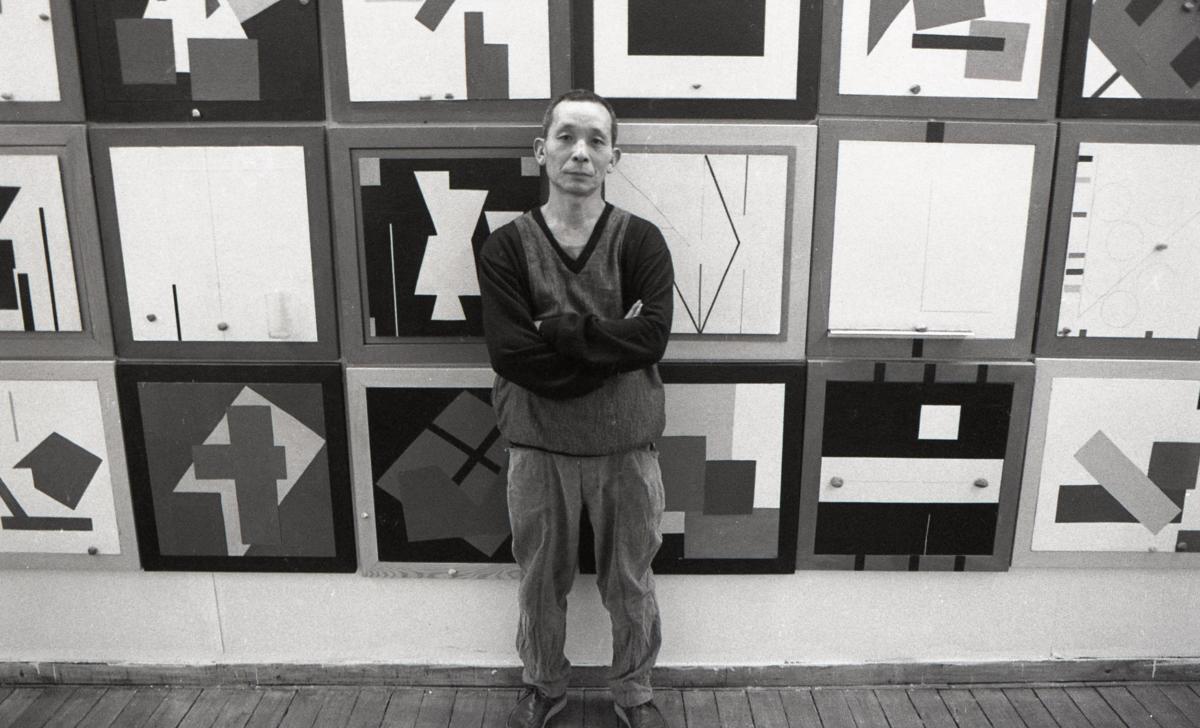

Exactly 50 years ago, Koji Kamoji completed his studies at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. Zbigniew Gostomski saw his graduation project and offered him an exhibition at the Foksal Gallery. Koji arranged it in the form of a small Japanese garden: he covered a section of the floor with a layer of white pebbles and placed his paintings on it. Today Koji says: ‘I don’t feel at all that I did those works a long time ago, that nothing connects me with them now . . . I’m still studying the same problem.’ Many photographs show the artist in the studio, kneeling or sitting in the lotus position in front of a painting, which lies on the floor, hidden from view by his silhouette. What is he doing with it? Today we know that he is not necessarily painting. He may be sticking wood bricks to it, or thin metal pipes, or ribbons of aluminium foil, or pebbles. Sometimes he leaves almost no trace of his activity on the white surface of the painting, which remains pure, save for a barely visible line or an imperceptible change in texture.

‘How did the gardener manage to create such a garden?’ Koji searches for the ideal, pursuing it constantly in concentration and silence. That is perhaps why he is fascinated with such periods in art as the Middle Ages, Egyptian art, or prehistoric times. Art in a vacuum of time, without dates and signatures, yet meaningful for and present in the life of its contemporaries.

He seldom uses stretched canvas; most often these are fibreboard or framed plywood panels, which produces a three-dimensional effect. That was the case with the pieces displayed on white pebbles in the Foksal Gallery garden. They could be referred to as ‘reliefs’, as Henryk Stażewski called his threedimensional paintings. But Koji not only attached objects to the surface of his early paintings; he also visualised the third dimension in a different way, by gouging all the way through the panel until a hole was made. He would produce several or a dozen of such larger or smaller holes. But in his case the procedure was not about three-dimensionality, as in Stażewski, or about aesthetically mutilating the painting and ripping it apart ‘destructively’, as Lucio Fontana did. Koji’s professor at the academy was Artur Nacht-Samborski, whom Koji held in high esteem, as he admitted later, and most of all for not interfering with what Koji did in his studio. He also explained how it all began: with scratching in the surface of the painting. As he scratched, he curiosity grew as to what lay ahead. Ahead there lay, of course, a hole, which shouldn’t come as a surprise. Nonetheless the artist was astounded. As he confesses, working his way through to the other side of the painting opened up for him a new horizon of infinite space, making him aware that the picture suddenly became but a means of achieving it. For a student of painting at art school, to pursue this kind of practice was an act of courage, as was exhibiting hole-ridden paintings at an art gallery, even one considered avant-garde.

Only a few years later, when I’d become familiar with the artist’s other works, did it occur to me that those paintings weren’t an avant-garde experiment or an artistic provocation. They showed that Koji was looking for them for a space wider than the surface of a canvas or even a garden. If they were but a means of achieving a goal, then the place of art shifted towards a different dimension, which was the artist’s actual area of inquiry. Evidence of this can be found in every exhibition, in every situation, where he presents his successive works, for example in the four-exhibition series Hole, Mirror, Line, Draught at the Foksal Gallery in 1975. Already working on the first of those shows, Koji obviously felt constrained by the exhibition space. He decided to make a hole in the wall, and made one, hammering his way through the plaster and brickwork. He was very happy to look through the hole at the new space. This became the culminating point in a precise yet simple arrangement of the four shows of the series; in the final one, the works — lightweight sheets of paper with cutout holes nearly touching the edges — hung from strings, fluttering in the draught.

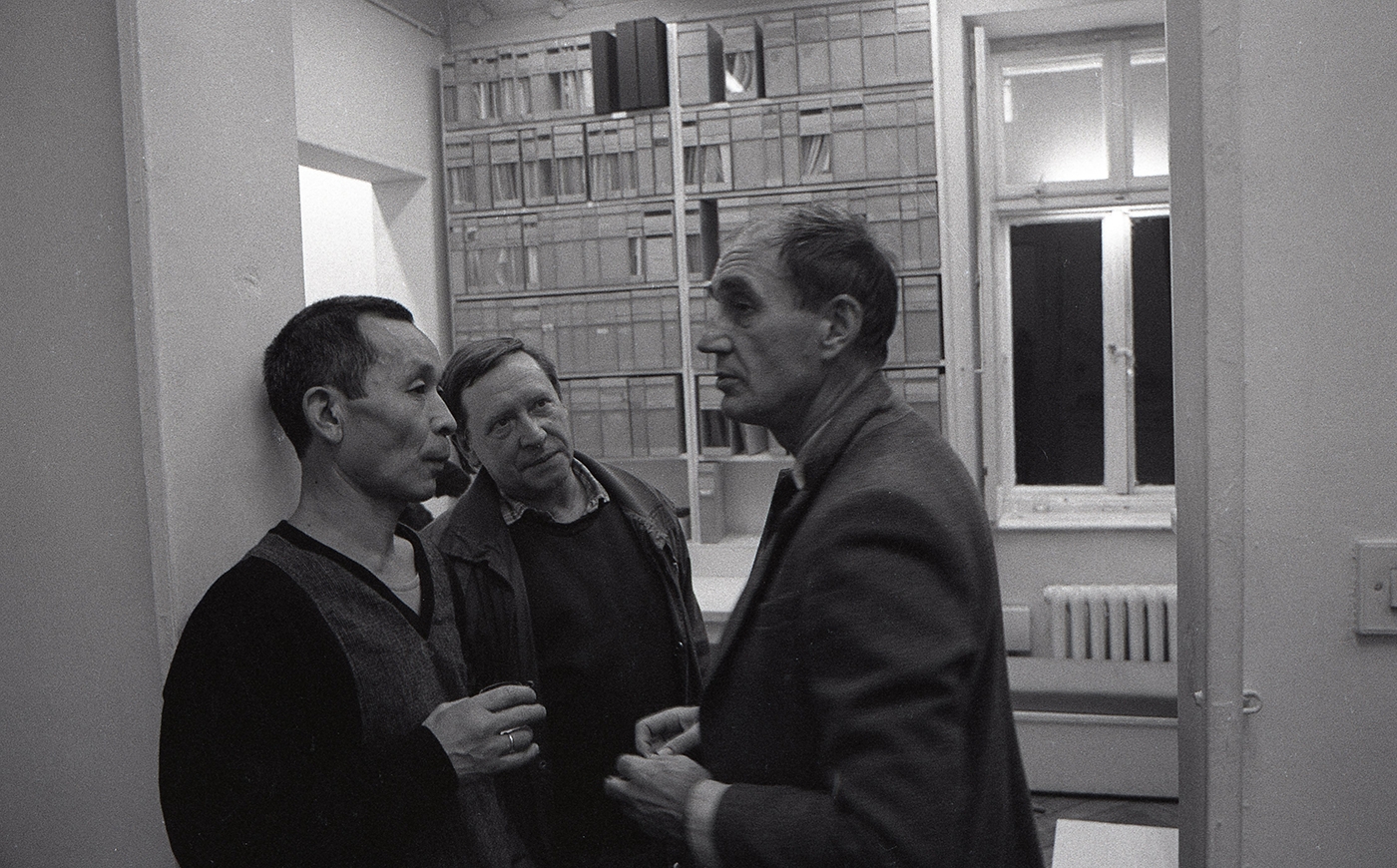

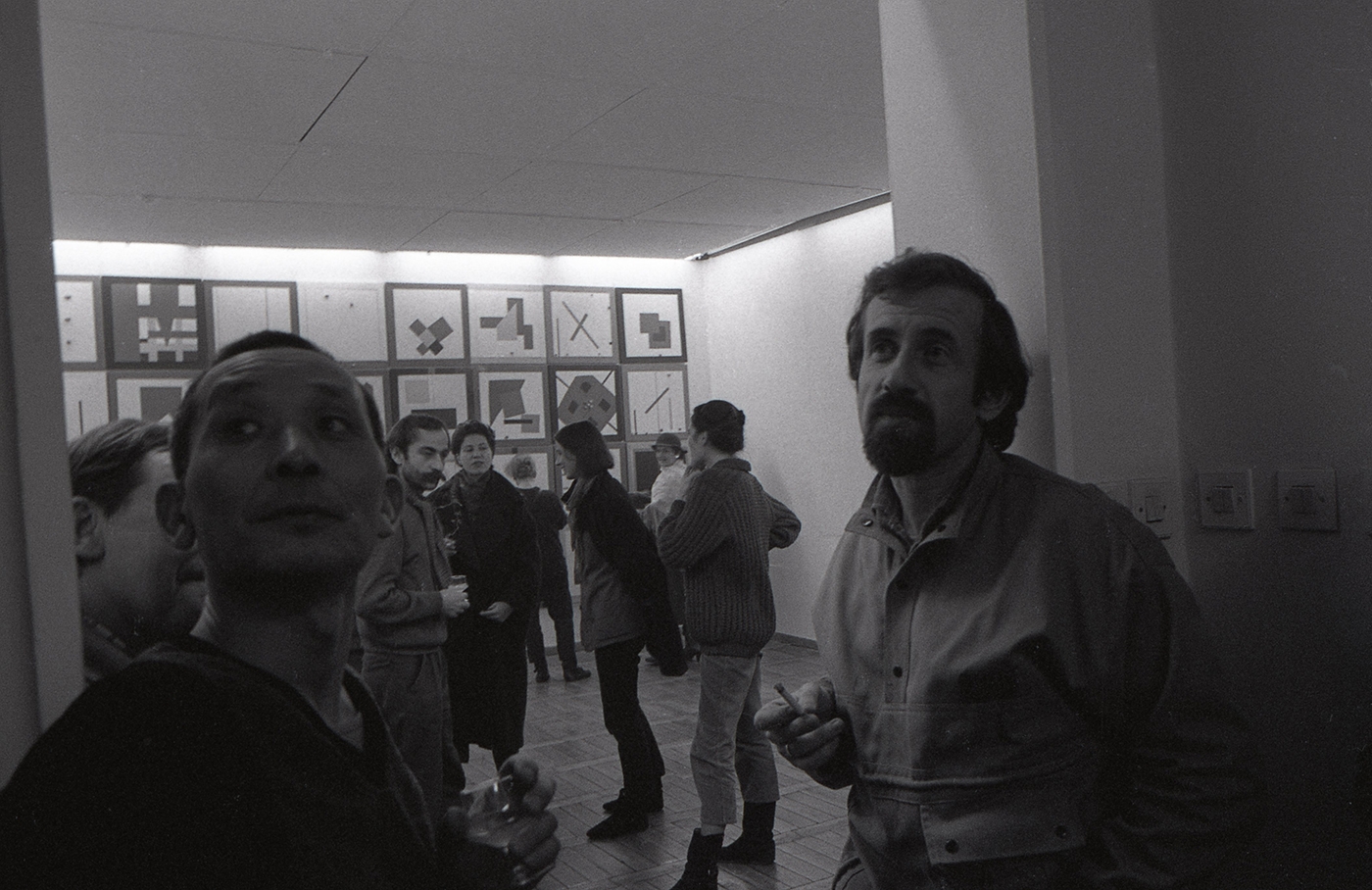

Opening of the exhibition ‘Middle Ages’, Foksal Gallery, 1986, photo. Wiesław Borowski

Many years later, conceiving an exhibition for the Galeria Biblioteka in Legionowo, he thought of water. Water is one of the primary motifs of his art, one he has engaged with in many ways; it has also been, as he’s often mentioned, essentially embedded in his memory since childhood. It appears as an image, a shortcut, or a symbol; sometimes it is materialised, and sometimes ‘ hidden’ in the very dream of it. That time the artist decided to look for it in the ground. After some hesitation, the gallery’s manager, Stefan Szydłowski, agreed for a well to be dug under the library’s parquet floor. It was a work that required effort, patience, and faith. Digging continued, with precast concrete rings added successively to secure the sides, until water was struck. Its exposed surface became — not only for the artist, but for all those present — a surprisingly true moment of art. It needs to be noted that in the context of the unknown or uncertain final effect (or discovery), the material/physical procedures and activities involved in the making of a work take on a ceremonial, ritual aspect. As Koji says, ‘I stray, but I do it with pleasure.’ When revelation occurs at last, it is accompanied by a sense of relief, peace, and fulfilment.

That was also the case when the artist was searching for the right and only right place to position an ordinary glass of water. I saw that glass in the perfectly silent 11th-century crypt of the Unser Lieben Frauen monastery in Magdeburg, standing on a stone floor, among simple Roman columns. Describing the situation, Koji said, ‘liny lights of day fall on it through tiny wall openings. The water receives and reflects them.’ There is also an added, barely perceptible sound element: the `voice of water, which could be audible in ourselves, fills the crypt silently, like a prayer to the walls and to the absent shadows of the monks.’ Giving ear to the ‘voice of water’, the voice of things — stone, plant, mirror, leaf, iron rod — comprises the most sublime sphere of Koji’s art. In the exhibition Evening — Boats of Reed at Kraków’s Starmach Gallery in 2006, the artist covered the floor with sheets of shiny metal to create an aluminium lake, intersected by flagstone paths, with aluminium boats sailing across it. As he reminisces, ‘In childhood, we were one with the reed boat . . . today I use aluminium instead of reed’. In combination with this recollection as well as the soundtrack — consisting of klezmer and Japanese flute music — the cool, metallic, ‘watery’ landscape of the exhibition, with a ‘min’ of hanging aluminium bands, creates a mood of focus and concentration. This song emerges from the memory of the site, reminding us that the gallery once used to be a Jewish prayer house.

According to the artist, listening to nature and to things — whether past or present — is the only way ‘to recover the things we tend to forget about, to retrieve the world we depart from. I would like to come by the form which will make them present.’ In Koji’s work, an image of memory, remembered and recorded, is meant to enable things, situated in a specific space, to move to a different one, to connect with the universe, with infinite space. Earth, water, stone, and everyday objects find their place in his works, in the shared matrix of the world of silence, harmony, and timeless duration.

Opening of the exhibition ‘Middle Ages’, Foksal Gallery, 1986, photo. Wiesław Borowski

The role of memory and reminiscence in Kamoji’s art makes one think of the work of Tadeusz Kantor. Both search for the deep roots of their art, which they perceive in fundamental and ultimate terms rather than current, short-term ones. The conveying of traces of memory into real situations shown in the exhibition, made present in contemporaneity, is an expression of a striving to preserve forgotten things. Childhood memories too are a frequent important motif in the work of the two artists. Despite those analogies, there are urany differences between them — first of all in the way they think of and express traces of memory in their art. Koji trusts his memory and is reconciled with the world; he returns to childhood memories, even the difficult ones, without becoming excited about it; he doesn’t comment on events and doesn’t dramatise them. His form is concise, symbolic, definitive. Kantor, in turn, grapples with memory, is deeply suspicious of it, though he keeps reaching back into the past and trying to save the remains torp from its ruins. His profound sense of transience offers no hope of preserving them. All Kantor wants is to shed light on a particular fragment surviving on the photographic plate of memory. He is interested in the dark aspects of the past, the wars and catastrophes that destroy people and humanity. Remembering his childhood room, he doesn’t see joy and serenity in it, but a ‘dark and littered cubbyhole’.

Already working on the first of those shows, Koji obviously felt constrained by the exhibition space. He decided to make a hole in the wali, and made one, hammering his way through the plaster and brickwork. He was very happy to look through the hole at the new space. This became the culminating point in a precise yet simple arrangement of the four shows of the series; in the final one, the works — lightweight sheets of paper with cutout holes nearly touching the edges — hung from strings, fluttering in the draught.

Koji Kamoji has always appreciated and admired Kantor’s work, though he has never been inspired by him. His own work exists beyond time, doesn’t vanish in nothingness, and doesn’t participate in the whirl of contemporary life and a ruined world. Kamoji tries in his works to leave a different trace preserved in time and space, beyond existential experience, in a world construed as an infinite totality. Creative work leads to a moment when this totality can be experienced. It doesn’t require particular alertness, haste, or constant mobilisation. Nor does it strive towards any preconceived goal. The artist doesn’t know where the process is taking him. Koji Kamoji says that perhaps one should yield to the force of gravity, or grope around like a blind man. The time of art is neither random nor privileged, yet unique. Finding a place in space, the work reaches the viewer not as a signal of the moment, but as a sign that allows him to reflect on all life and the world. With its maker, it goes out to ‘meet time and space, to meet nature; it’s the only moment for us, a moment like no other.’ In the metaphor of the garden, which for Koji is not a metaphor at all but a concrete situation, the ‘moment is heightened and illuminated through the immutability of the garden. A meeting, a farewell, and immutability’. And his admiration in the question: ‘How did the gardener manage to create such a garden?’ Koji searches for the ideal, pursuing it constantly in concentration and silence. That is perhaps why he is fascinated with such periods in art as the Middle Ages, Egyptian art, or prehistoric times. Art in a vacuum of time, without dates and signatures, yet meaningful for and present in the life of its contemporaries. He went to Lascaux to see the cave paintings, he peregrinated to Chartres in search of traces of art emerging from an abyss of time. He devoted a series of paintings to his reflections on the Middle Ages, noting down a litany of features distinguishing the era from the present times: ‘prayer — progress . . . sense — mind . . . no hurry — hurry’ and so on. The idea was to make the Middle Ages, a period of intense concentration and spiritual elation, present in his paintings. In Koji’s work, the Medieval Period becomes a symbolic garden, where images find their place and meaning, like rocks in a natural garden, the stones and bricks of a temple, which are also the ‘sediments of memory, witnesses of events, fossilised emotions’. Koji seeks for his art a pure place and time, freed from a legacy of fear and the complexity of contemporary civilisation. He employs the simplest visual solutions: concise and formally spare.

On the one hand, we notice in them points, strokes, parallel or intersecting lines, semi- or full circles. As Lech Strangret pointed out, the visual code has for centuries served as a reference to the invisible. This code however isn’t too important in these works, which by no means should be classified as abstract for, for, on the other hand, we find in them stones, sand, earth, water, metal, ordinary real objects, with their own weight, material structure, and function in nature and the human environment. But these objects don’t push themselves to the front, don’t overwhelm, for what matters in the first place is their transformation in the work. The most important thing is the invisible touch of the object, the faint trace of the artist’s hand as he paints, the gentle gust of wind, the reflection of light from the surface of water, the ripples on it. And the special voice of the objects. It is — like the garden — an image of the harmony of things as well as a voice of silence, which the artist wants to convey and which may reach us too. In the garden of Koji Kamoji’s art we are able to experience the mysterious mechanism of the world, its nostalgic beauty, and to reflect on it as a totality.

Opening of the exhibition ‘Middle Ages’, Foksal Gallery, 1986, photo. Wiesław Borowski

As I reflect on the Foksal Gallery’s long-time association with Koji Kamoji, I realise that we came to understand the essence of his art and the ‘fullness’ he pursues only gradually, during his successive exhibitions, all of which were important in their own right. Initially, the diversity of his forms of expression — painting, installation, the ever-different objects he used — could be deceptive, causing us to see them separately. It was only when one had gotten more familiar with Koji and his art that the vision, meaning, and significance of each of his works became clear. Koji was and is the Foksal Gallery’s good spirit, but also our timeproven friend. His special skill — the ability to be on good terms with everyone, everywhere — could be felt from the beginning. I think it’s a gift that is Japanese and Oriental rather than Polish or European. As a result, the viewer can feel within the exhibition space as if he were at his own studio. Koji’s presence at the Foksal and the discreet and effective support he provided to its daily operations was invaluable and utterly selfless. It was the gallery’s policy that exhibitions were arranged by the artists themselves rather than the curators. When the featured artist was unavailable, we’d ask other artists for help. In such situations, Zbigniew Gostomski and Koji Kamoji were invaluable, putting the show in order precisely and selflessly.

Koji was always interested in other artists and their exhibitions. He appreciated many, but felt the closest affinity artistically with Henryk Stażewski, Edward Krasinski, Andrzej Szewczyk, or Zygmunt Targowski, whom he was friends with. He actually introduced the latter to the gallery: Targowski had only one exhibition, Photographs, but it was phenomenal (he died in a motorcycle accident when it was on display). Koji shared many ideas with philosopher Stanislaw Cichowicz, who was a frequent guest at the gallery and presented his projects here. The two of us frequently went to Krakow together to watch the rehearsals and performances of Kantor’s Cricot 2 theatre, which invariably fascinated him.

But his highest esteem was reserved for Henryk Stażewski, in whose paintings he saw focus, silence, and joy, qualities that appealed to his own sensibility; Koji always gladly participated in joint exhibitions with Stażewski. He remembers to this day a piece of advice he got from him: ‘Change slowly’. Koji went with me to London when the Polish Cultural Institute there, already under ‘Solidarity’ management, invited us to design an exhibition of Stażewski’s paintings. As he later reminisced, this proved a challenge, since the Institute’s beautiful lobby, with its wainscoted walls and chandeliers, wasn’t the best space for such a presentation. But Koji found a solution and the show was a success.

Opening of the exhibition ‘Middle Ages’, Foksal Gallery, 1986, photo. Wiesław Borowski

Earlier, in 1982, he ‘saved’ the exhibition Et change entre artistes 1931-1982. Pologne-USA at the Musee d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, which was important for us. It featured the works of over 30 artists, including famous American artists, who didn’t attend however. On the day before the launch we still weren’t happy with the show, and Koji called it ‘dede’. He took matters in his hands and the museum’s director, Susanne Page, allowed us (Koji, Anka Ptaszkowska, and myself) to remain on the premises for the night. During that night, Koji changed everything. In the morning, the exhibition looked good: it had, as he said himself, become very appealing, with a lively mood.

Koji not only attached objects to the surface of his early paintings; he also visualised the third dimension in a different way, by gouging all the way through the panel until a hole was made. He would produce several or a dozen of such larger or smaller holes. But in his case the procedure was not about three-dimensionality, as in Stażewski, or about aesthetically mutilating the painting and ripping it apart ‘destructively’, as Lucio Fontana did.

In conclusion, I’d like to mention yet another of Koji’s creative interventions in support of the Foksal Gallery. In the 1980s, when the mood in the whole country, and so also in the gallery, was one of gloom, hopelessness, and lack of prospects, we talked a lot about a collection. This discussion had been occupying us for some years, when Krzysztof Wodiczko and Andrzej Turowski were still present to partake in it. Now we were returning to the subject, thinking about a collection that would comprise a certain canon of Polish art, or about an international collection, as we came up with all kinds of ideas, sometimes perfidious, sometimes megalomaniac. We sought actual possibilities too, suggesting specific forms and locations of such a collection to various official bodies (including the Ministry of Culture). Those efforts were all bound to fail. Then one day Koji came and pitched the idea of the Nonexistent Museum. The Foksal Gallery would ask selected Polish and international artists to donate their best works, one each. The donated work would physically remain in the artist’s studio. The idea was for each work in the Nonexistent Museum to be unique and to remain in the same setting in which it had originally been made. The Museum would be invisible and kept in secret. All that was needed for the work and its documentation to be added to the collection register was a donation deed. While the Nonexistent Museum was a feasible idea at the time due to the gallery’s close ties with its artists, it remained but an interesting project. Nonetheless, the idea shows that for Koji lasting relationships are most important, and he believes to this day that the Nonexistent Museum could yet be founded.

The text first appeared in the book edited by Maria Brewińska on the occasion of the exhibition Koji Kamoji. Silence and the Will to Live at Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw

Text licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported licence

Imprint

| Author | Maria Brewińska (ed.) |

| Title | Koji Kamoji. Silence and the Will to Live |

| Publisher | Zachęta – National Gallery of Art |

| Published | 2018 Warsaw |

| Index | Foksal Gallery Koji Kamoji Maria Brewińska Wiesław Borowski Zachęta – National Gallery of Art |