“… In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.”[1]

In 1946 the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges published the short story “On Exactitude in Science” – cited above – in which he imagined a map the exact size of the territory it covers.[2]

In that story, cartography has been developed to an unimaginable degree, which allows art and science to essentially level nature. Eventually, the map is pushed aside by the following generations, and its ruins, inhabited by animals and beggars, are only visible in distant corners of the empire. In this story, Borges lays the complexity of depicting the world – the territory – in front of the reader. He presents a certain narrative of failure in representation underlining the uniqueness of the real, natural world with its multidimensionality being lost when translated into a flat surface. The core of this narrative lies in the belief in the steadfastness of nature: something that is understood rather as a constant than as a construct.

The Borgesian map might come in handy when we no longer have a distinguishable territory – when everything terrestrial has attained a different nature and moved beyond the ways in which we understand it. When the notion of nature itself has become a shallow, half-empty shell loaded with floating signifiers. In these circumstances, we might need something to hold onto that can assist us in surviving in this brave new world. Something that we can look back on while defining our present moment. In other words, we might need a good map to navigate across the many surfaces of our time, some of which slither away as soon as we reach them, while others are too intangible to anchor to.

Big Data Times

“The surface of Mars, molecular structures of proteins, shapes of individual neurons in the body of a lab-test worm, satellite images of all the major storm patterns of the last thirty years, millions of 3D embryo and MRI scans, hidden camera wildlife footage from all over the planet, databases full of human faces and DNA strands.”[3]

And so forth.

The gaze of our contemporaries has been instrumentalised by beneficiaries, almost as foretold in science fiction. This exhibition looks at the emergence of seeing divorced from the carrier of the central instrument – an eye – through the lens of sci-fi.

The rapid growth in technology has provided us with new insights about the most microscopic particles, as well as matters of planetary scale. Today, almost all aspects of human, and increasingly non-human, lives are registered or modelled by all-embracing software. Data collection and processing have long transcended the limits of our planet, becoming tools with which to map surfaces across the Earth and beyond it. All of these aforementioned, previously unexplored territories of data are first encountered on a visual level.

Valuable information is constantly transmitted from one end to another, but only if we are able to distinguish between information and noise, and more precisely, work around the latter. It’s often not simple: the core of this new reality lies in the uncertainty and intangibility of these materials, or as Hito Steyerl has summarised: “Not seeing anything intelligible is the new normal.”[4]

In this situation an untrained eye couldn’t possibly see much worth looking at in the contemporary data maze:

“Information is passed on as a set of signals that cannot be picked up by human senses. Contemporary perception is machinic to large degrees. […] Vision loses importance and is replaced by filtering, decrypting, and pattern recognition. […] ”

“But noise is not nothing. On the contrary, noise is a huge issue, not only for the NSA but for machinic modes of perception as a whole.”[5]

To decrypt means to see, and often a method of pattern recognition is applied to data by computation devices trained to recognise regularities and repetitions. Therefore, in addition to what is directly experienced by or between humans, there are also many visual patterns that are sourced, processed and “viewed” between machines and algorithms, with only traces of them reaching the human eye. It is often these “seeing machines” which are at the frontier of actually experiencing the world for us: like the Dawn mission probe flying to the small planet Ceres, or a deep-sea rover filming and encountering life forms hitherto unknown to humans. The world is full of encounters that occur between myriads of non-human beings navigating both immediate and faraway surroundings with a variety of sensory mechanisms and unique ways of seeing. If not seeing anything intelligible is the new normality, then this state of information decay is being propagated almost exclusively by various types of artificial eyes whose operating procedures are becoming increasingly independent of their original programming.

Questioning the intelligibility of images leads to the politics of (and behind) seeing in the sense of accessing: a central topic in the current discourse of data processing, collecting and transmission. The question of what we are able to see concerns a far larger context than visual culture: Steyerl exemplifies the political angle through (information) warfare production, where a single unit of data may have far-reaching consequences, shifting the discourse in an entirely new direction. As such, the purposeful (mis-) interpretation of an image can be used to sway multiple parties with wildly differing, if not conflicting interests, further fuelling an endless loop of conspiracy theories, political power struggles and clandestine military ops.

The gaze of our contemporaries has been instrumentalised by beneficiaries, almost as foretold in science fiction. This exhibition looks at the emergence of seeing divorced from the carrier of the central instrument – an eye – through the lens of sci-fi. “If only you could see what I’ve seen with your eyes,” says the replicant Roy Batty to the designer who created his eyes in Ridley Scott’s cult sci-fi film Blade Runner (1982). Based on Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), Scott summarises the conflicting dynamics of a technology-based realm where genetically engineered robots and humans coexist. Although the replicant Batty is increasingly consumed by the need for self-preservation, an inalienable human birthright, his synthetic origins deny him any life beyond his expiration date. Thinking of the near future, Benjamin Bratton writes that the current discourse on racism predicts the nature of the human-machine relationship, or even that between any artificial and carbon-based life forms.[6]

For that, the replicants imagined in the late 1960s and early 1980s were born too early: their congenital rights kit didn’t include the right to life.

This imaginary scenario of Dick and Scott has been brought to life by the many branches of technocratic enterprises and research parties across the planet. The question of what these non-human life forms – sometimes similar to domestic appliances, in other cases resembling animals or revealing anthropomorphic tendencies – see during their routine behaviour remains, to some extent, unresolved. At this point, we can only rely on the converted versions spat out at us, and – as always – on imagination, which in itself is under attack by hyperreal imagery and the looming virtual reality revolution.

Katja Novitskova’s Ulme

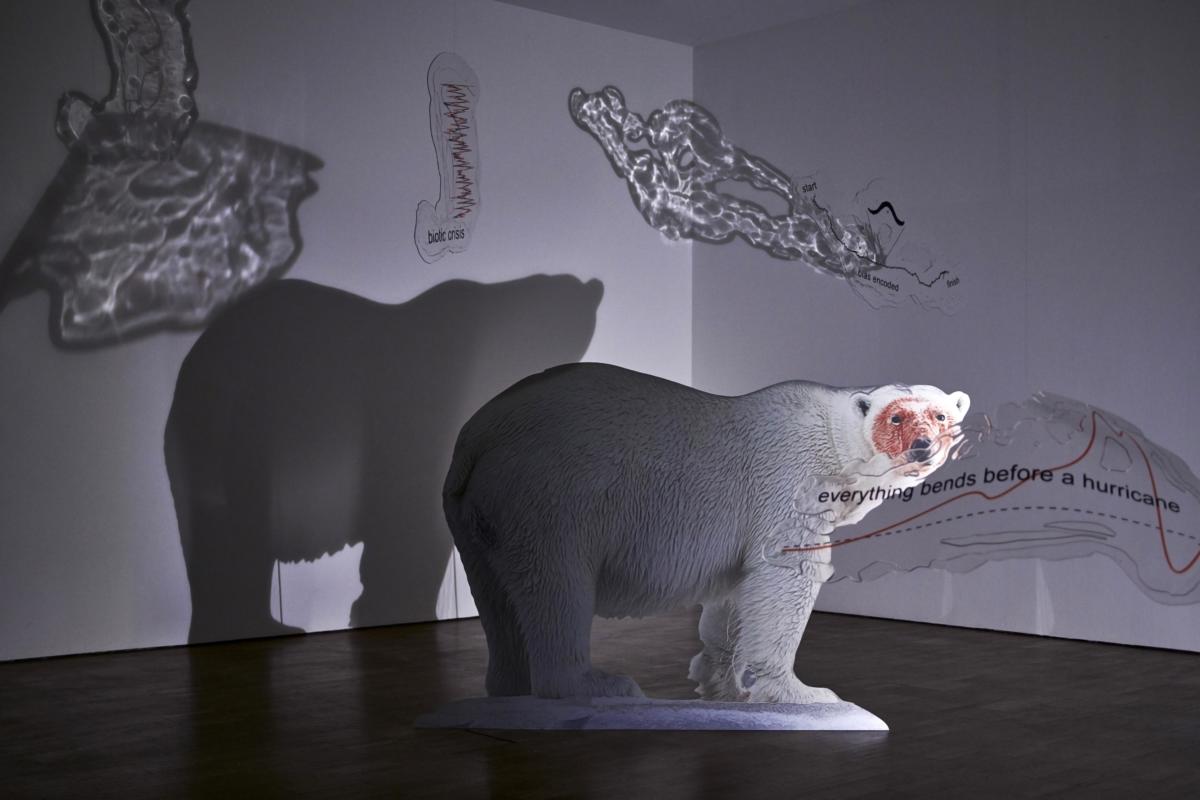

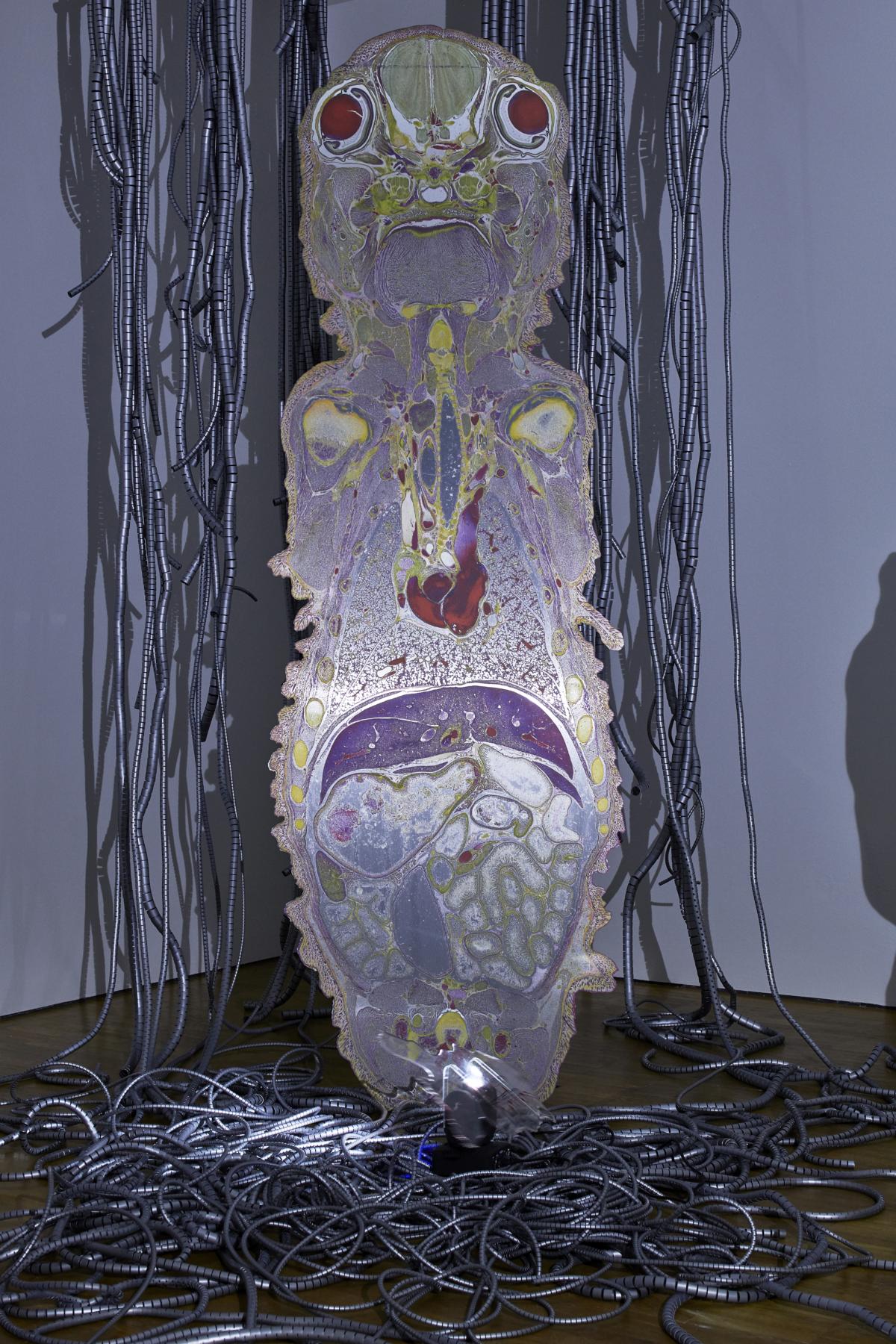

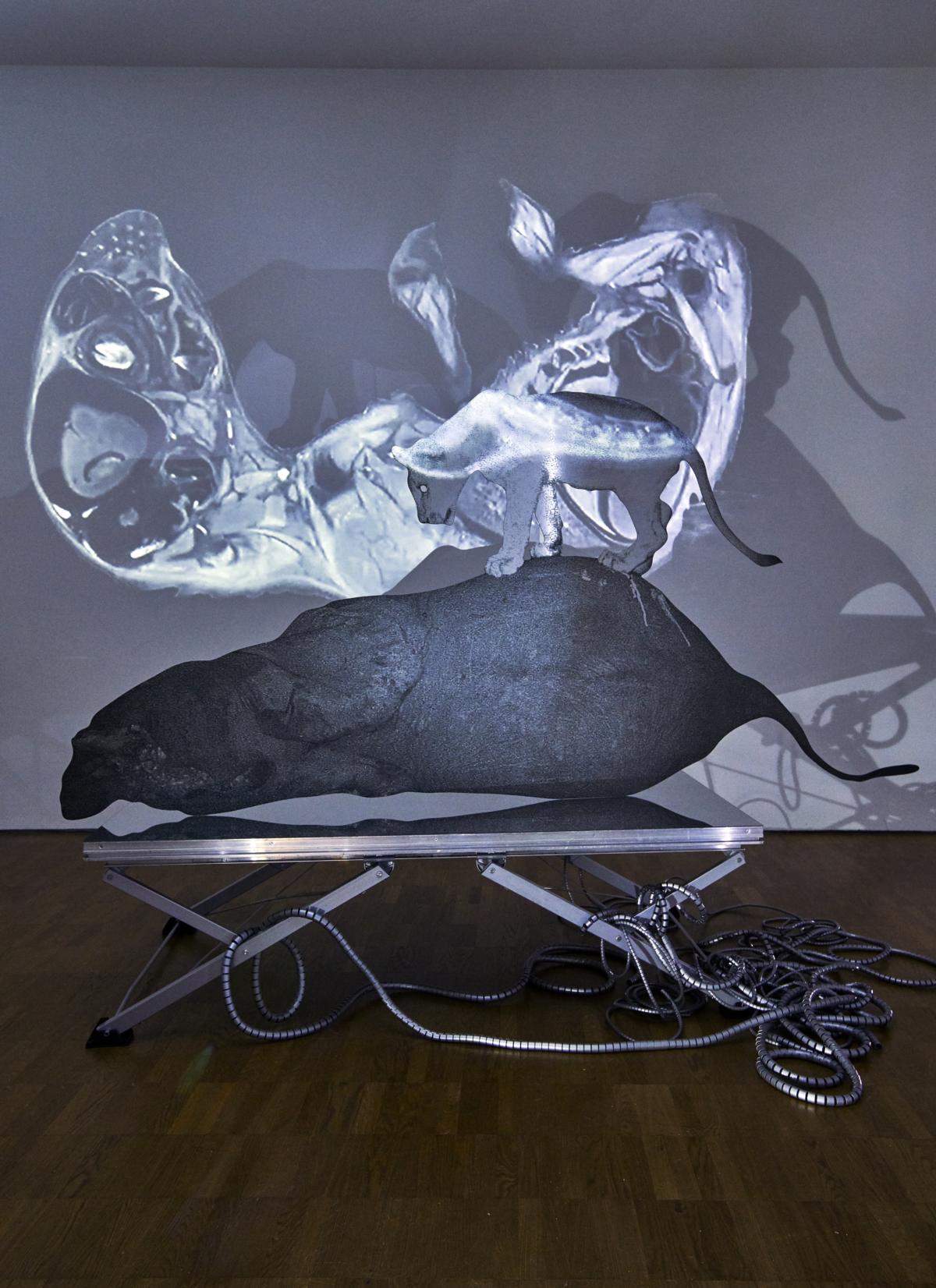

Katja Novitskova takes the aforementioned premise as a working catalyst within the exhibition If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes. Her artistic role here is in some ways that of a medium: she is a filtering organism receiving data in its most picturesque form from various processes, and she then forwards it to the recipient in a carefully synthesised manner.

Although Novitskova has been considered globally to be among the pioneers of post-Internet art since launching a project well-known for its concurrent publication, Post Internet Survival Guide 2010 in 2011, which looked at the ecology of a severe ongoing merging of matter, social and visual information at that time, as well as long having been the sole representative of that strand of thought linked to Estonia, her practice can also be associated with her country of origin more broadly.

Novitskova’s practice has regularly been framed by the notion of the post-Internet: a movement within the post-digital realm drawing mainly from corporate aesthetics, Internet-based phenomena and image circulation in general. Using stock photography and ready-made objects, it is a reflection of the Internet and the data it houses rather than something that is actively executed online. Although used widely, the term lacks any inherent specific content and is often used more as a catch-all to describe any contemporary art practice rising from the world wide web. The prefix “post” might – and might not – refer to something that takes place after the Internet, but rather than excluding it points to a certain type of experience. One way to look at it would be to point out the angle of working, researching and producing, where artists connected with that concept directly execute their works after using the Internet and gathering materials online. It could be argued that today all artistic research is done online, not to mention the presence of technology or online media platforms in our lives in general. Yet, there’s a noteworthy difference between, for instance, an artist whose work circles directly around sociopolitical aspects increasingly brought to attention by guerilla media or activists sharing footage online, and an artist whose practice is dependent on data processing and imagery unequivocally born online. Quite often – and in the case of Novitskova and many others related to this particular practice – the imagery gets taken from its initial surroundings and is executed tangibly, in the physical form of an installation within a gallery space.

Although Novitskova has been considered globally to be among the pioneers of post-Internet art since launching a project well-known for its concurrent publication, Post Internet Survival Guide 2010 in 2011, which looked at the ecology of a severe ongoing merging of matter, social and visual information at that time, as well as long having been the sole representative of that strand of thought linked to Estonia, her practice can also be associated with her country of origin more broadly. Novitskova, having received only a little of her art education in Estonia, has developed her career in international circles in Amsterdam and Berlin. It could be argued that Novitskova’s use of emerging technologies walks a path not too dissimilar to that of Estonia itself, a well-known poster-child of early and aggressive digitisation of government services. The country’s commitment to a techno-centric vision of effective governance has remained largely unchanged throughout the years, serving as a cathartic shedding of the corrupt and monolithic Soviet bureaucracy which preceded it. Although a few fringe voices have, as political sport, taken to criticising the validity of nation-wide electronic voting (a world-first), the overall march towards a digital singularity of citizen-state interactions remains largely unchanged and unchallenged. Novitskova’s art, often maintaining a level of permeating unease regarding our technological reality and the future this may lead to, stands in stark contrast to the concept of E-stonia and the optimistic promise of a fully digitised democracy, where technology is more self than other.

The Estonian affinity for such futuristic visions and sci-fi in general is not particularly new: in 1970, the notion of ulme was rooted in the Estonian language by the Estonian writer Henn-Kaarel Hellat to capture the meaning of sci-fi without being a word-for-word equivalent of the English word. Later, the term developed to refer not only to sci-fi, but to the fantasy and horror genres as well. Hellat’s proposal was a reflection of the blooming situation within the field of sci-fi in the Soviet era: not only was the growth in the number of published sci-fi books striking at this time, but 60% of the students in Moscow enrolled in courses in technology or natural sciences explained their interest as having been directly drawn from some sci-fi narrative.[7]

The Soviet Union, at the peak of the Cold War, channelled most of its resources into the military and sciences that catered to it, and this resulted in an increase in related themes in film and fiction.

The realm of visual production today is becoming rapidly dominated by the aesthetics of global corporations. The intertwining of science with profitable private interests has already created a basis for responses to rise from various levels, and contemporary sci-fi, both in film and literature, has also had its say. The logic behind contemporary art as generally a less narrative practice now involves exploring the domain of what’s behind what’s visible to us in a more ambivalent way. Novisktova filters images from this situation, turning these large processes into the fragmented language of installation. Novitskova’s objects are far from unconditionally stabilised within the realms of sculpture, photography or installation; instead they are rather liminal. Erected to date mostly within rigid white cube environments, and increasingly presented in more dispersed iterations than seen here, they act with a certain sense of alien otherness. Standing scattered in gallery spaces too uncanny to fully belong to our present world just yet, but recognizable enough in their imminence, they are bound together as pan-historical curiosities. Venus Lau has described Novitskova’s practice as a combination of dichotomies in different registers:

“Novitskova links both sides of several dichotomies: human and nature, pre-human and posthuman, ancient history and the distant future, abstract and concrete, nature and civilization. The work becomes a transition between two extremes, offering both a continuum and the possibility of homogenization. When the dichotomy dissipates, the project becomes a vanishing mediator.”[8]

It could be argued that Novitskova’s use of emerging technologies walks a path not too dissimilar to that of Estonia itself, a well-known poster-child of early and aggressive digitisation of government services. The country’s commitment to a techno-centric vision of effective governance has remained largely unchanged throughout the years, serving as a cathartic shedding of the corrupt and monolithic Soviet bureaucracy which preceded it.

Pinpointing the contemporaneity – or archaic tendencies, or futurist ideas for that matter – in Novitskova’s practice is therefore a rather ambiguous act. When approached through the choice of materials – mostly polymers with variable melting points combined with ready-made objects, video, light and sound – it’s highly characteristic of the production culture of the present day. It’s also characteristic of the physical bodies of those machines processing data. However, when looked at in terms of the content they carry we might want to reconsider and place them as part of another, long-passed realm that is known to us through archaeological excavations and fragments from other times. Novitskova, rather than commenting on the observable moment, transforms these various incarnations of data from different eras over many millennia into an immersive environment that depicts the world to come. Working with these possibilities provided by the vast amount of data available, the question of time arises again. According to our use of language, Steyerl suggests that we are living in the time of the Data Neolithic:

“The vocabulary deployed for separating signal and noise is surprisingly pastoral: data ‘farming’ and ‘harvesting’, ‘mining’ and ‘extraction’ are embraced as if we lived through another massive neolithic revolution with its own kind of magic formulas.

All sorts of agricultural and mining technologies – that were developed during the neolithic – are reinvented to apply to data. The stones and ores of the past are replaced by silicone and rare earth minerals, while a Minecraft paradigm of extraction describes the processing of minerals into elements of information architecture.”[9]

By pointing this out, Steyerl places us at the dawn of culture: what is understood to be characteristic of the beginning of our civilisation might now be found recurring through the present-day activities defined by language and image-making. Even if it’s not the Data Neolithic – or rather if the coming generations collectively decide to give it another label – we are undoubtedly at the dawn of something transformative. This time, in comparison to every previous epoch since the beginning of the Enlightenment, we might actually look back and inside rather than towards the future. What we are about to see is something that has always been there but has been impossible to see with the always stationary naked eye: it is the surface of Mars, molecular structures of proteins, shapes of individual neurons in the body of a lab-test worm, satellite images of all the major storm patterns of the last thirty years, millions of 3D embryo and MRI scans, hidden camera wildlife footage from all over the planet, databases full of human faces and DNA strands.

Nature, Revisited

The materials looked at within this exhibition are not essentially new: distant celestial bodies and the smallest particles existed long before us; only now, when brought closer, our grasp of them is more complex. Describing Novitskova’s use of scientific materials in correlation with recent, sometimes speculative scientific developments, the writer Nora Khan has observed that “they were always there, but now, when we looked back out into space, they were clear, live. Unobserved for a billion years until recreated in a model.”[10]

The scope of the source pool of imagery is exceptionally broad, consisting both of new data structures and (re-) discoveries made possible through machinic vision.

If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes aims to observe this matter closely, with the necessary tools now in our hands. The exhibition takes the visitor from the traditional surroundings of Venice several millennia into the future, placed in a claustrophobic space divorced from its initial purpose. Encounters here will be held between those with both human and synthetic eyes. The work is not just about what you see, but also about what you might experience navigating the space. A time capsule where visual artefacts from the current moment, fossilised in synthetic resin, might get re-discovered and then studied in the distant future, when the world as we know it is no longer there. It could also be interpreted as a re-enactment of the Borgesian map handed out to us: a carefully compiled and spatially laid out collection of artefacts depicting the depths and distances of the current day at its most intensive level. While revisiting the planet Earth at its peak of transformative processes in the future, one might need this map for the journey to locate its premise. And probably this time it won’t be thrown away or dismissed, as what used to exist only beneath the surface is now no longer there; instead, its vast relics will be found scattered within this geographic location.

This text was initially written for Estonian Pavilion at 57th Venice Biennale that displayed Katja Novitskova’s solo show “If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes”. The catalgoue was co-published by Sternberg Press and CCA Estonia (2017).

[1] Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science,” A Universal History of Infamy. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1975, p. 131. Translated by Norman Thomas di Giovanni.

[2] This story was first published in 1946 under the name B. Lynch Davis, a joint pseudonym of Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares.

[3] Kati Ilves and Katja Novitskova’s exhibition proposal for the Estonian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale.

[4] Hito Steyerl, “A Sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis-)Recognition,” e-flux, no. 72 (April 2016), www.e-flux.com/journal/72/60480/a-sea-of-data-apophenia-and-pattern-mis-recognition/.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Benjamin Bratton, “The Black Stack,” The Internet Does Not Exist. e-flux Journal. Sternberg Press, 2015, p. 289.

[7] Henn-Kaarel Hellat, “Ilukirjanduse põnevad provintsid,” Sirp ja Vasar, no. 38 (September 1970): pp. 3, 5.

[8] Venus Lau, “Plastiglomerates of Images,” Dawn Mission. Hamburg: Kunstverein exhibition catalogue, 2016, p. 209.

[9] Hito Steyerl, “A Sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis-)Recognition,” e-flux, no.72 (April 2016), www.e-flux.com/journal/72/60480/a-sea-of-data-apophenia-and-pattern-mis-recognition/, www.e-flux.com/journal/72/60480/a-sea-of-data-apophenia-and-pattern-mis-recognition/.

[10] Nora Khan, “Simulate Deep Future,” Dawn Mission. Hamburg: Kunstverein exhibition catalogue, 2016, p. 30.

Imprint

| Artist | Katja Novitskova |

| Exhibition | If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen with Your Eyes. Stage 2 |

| Place / venue | Kumu Art Museum, Tallin |

| Dates | February 23 – June 10, 2018 |

| Curated by | Kati Ilves |

| Website | kunstimuuseum.ekm.ee/en |

| Index |