Adam Mazur: You’re the Chair of the Arton Foundation. What is the foundation?

Marika Kuźmicz: I’d call it a centre of permanent research and a permanent learning process concerning searching archives, exploring them and deliberating about how to show people what you’ve managed to discover. An institution can’t operate entirely on the basis of navel gazing. So, in that respect, I try to find various ways of showing what we’ve found.

Formally speaking, the foundation’s an NGO. You established it together with a team of co-workers. How would you describe the organisation?

At the moment, I’m working with four people. Each of us is engaging with a different archive. I think that’s the best practice. The ideal situation is when someone engages with an archive from the outset to the point where that archive is publicly revealed. Then the people involved in working on a collection are also a source of knowledge about particular archives.

Are they art historians?

Art historians or future art historians. We succeeded in setting up a digitisation studio where two people work, sometimes three, as and when necessary. At the moment, I’m working with two of my former students, Paulina Brol and Julia Ciunowicz, and with Julia Kusiak. There’s also a fundraiser.

How would you describe the method developed by the team?

The Arton Foundation has been operating since July 2010. It’s focused on a specific moment in the history of post-war art in Poland, primarily the nineteen seventies, though it does encompass the sixties, as well. And our method of work? Well, before you reach the point of inventorying, of creating an archive, first of all you have to find it. I’m particularly interested in the kind of phenomena and names that are somehow unobvious… you may come across traces of them in catalogues or on invitations or during other searches. There are always threads that are just the start of a skein and you have to give them a tug. I do that partly by turning to my various contacts, but I also trust my intuition. Sometimes I search in places which just might, perhaps, contain the resource I’m after, but sometimes archives home in on me of their own accord.

Jadwiga Singer, ‘Destrukcja’, 16 mm film, 1979 (found in 2018)

For instance?

Recently, Jadwiga Singer’s archive has undoubtedly engaged me profoundly. It was literally discovered, but I’d been looking for it for several years. A few people who actually had some inkling of her name told me that there was certainly no such archive. Even Grzegorz Zgraja, a fellow founder of the Laboratorium Technik Prezentacyjnych / Presentation Techniques Laboratory, said he thought that, knowing Jadwiga, it was impossible for her work to have survived. And yet, as things transpired, it did. I wrote a piece about her, recalling her as an artist who had existed, but whose archive had most probably perished. After I’d published it on the foundation’s website, her family got in touch with me and it turned out that they had her archive. And I’d actually been following Singer’s traces for some four years or so.

Who was Singer and why is she of such interest to you?

Jadwiga Singer came from Katowice and she studied graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts there, starting in 1975. At the time, it was a branch of the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts and a fairly paltry, stuck-in-the-mud school. That was where the group she co-founded, the Presentation Techniques Laboratory, was born. The members were primarily interested in film, video and photography. Traditional graphic design work and techniques held no special attraction for them. The group broke up around the time when martial law was in force. Some of the members went abroad, but Jadwiga stayed in Poland. She was married, and for the second time, at that. Her husband, Jacek Singer, was also a founding member of the Laboratory. Then her life took a dramatic turn. On the one hand, it was a personal drama. Her marriage fell apart. On the other hand, she didn’t have any support from anywhere in the arts community. She was working non-stop, but she didn’t actually have anywhere to exhibit what she was creating. Then financial problems added themselves to the mix and, basically, she ‘vanished into thin air’. Before I met up with her family, I’d even been having difficulty establishing the key dates in her life. Her ex-husband’s sister phoned me and invited me to Katowice. There, at a spot between Katowice and Zabrze, was everything that Jadwiga had kept and it turned out to be a major resource… several thousand negatives, several hundred photographs, sixteen and eighteen millimetre films, video cassettes…

Does an archive like that have a chance of changing perceptions of art?

Very probably, if there’s something on those videos that’ll change our view of what we know about early work with video in Poland in the nineteen seventies. We know the names and we know more or less how many works there were. And there weren’t all that many of them. Until now, we thought that it was only Jolanta Marcolla, Izabella Gustowska and Ewa Partum, but Singer also created video works. Before her family contacted me, I’d been to Katowice and followed in her tracks, visiting places where she might have been. For instance, I went to the gorgeous, nineteen-thirties building that houses the academy and to a stairwell there. It’s an important spot because the Laboratory group created an extraordinary environment there. In the photos, it looks quite uncanny. They transformed the entire space into a kind of gesamtkunstwerk. Portraits were the leitmotif. I went to have a look at that stairwell. I went to the studio Singer worked in at the academy and I went to the Silesian University of Technology, because that was where the Laboratory group had a bit of back-door access to video cameras. I was trying to reconstruct the geography of Jadwiga’s life. And then, I found myself in an attic and there it was, all of it… and it was hard to believe not only just how much of there was, but also that it was in such good condition.

Do you often identify with the women artists you research as part of the foundation’s programme?

It’s true that I sink into a kind of profound fusion with whatever I’m currently working on and it’s sometimes hard for me to move from one thing to another because I’m so immersed. In this instance, Jadwiga Singer is dead, but when I’m dealing with living artists, then I’m working very intensively with them and we grow very close on many an occasion.

So, you find an archive in an attic. What happens next? In terms of logistics and working methods, I mean.

More than anything, I like to pack everything up and transfer it all to one place if that’s possible. Sometimes it can’t be done, but in this case, it could. I packed everything up and Jadwiga Singer’s family said I could take it all, but it would best if I did it at once, that same day. So I packed it up and took it. Then the normal inventorying process began. To be on the safe side, I do try to scan everything and, after that, we do any selecting that might be called for. Everything that’s in an archive is inventoried and then made available in the database. I like to show exhibitions while that’s happening, even if the inventorying and digitisation is still in progress. It enables me to get my bearings about things and about what the foundation’s repository[1] users and gallery visitors are most interested in. Sometimes that coincides with my interests and sometimes, it doesn’t. It’s good to verify that from a distance.

You also do the fund-raising for all that work. Where do you look for money?

I apply for funding, mainly Polish, from the Ministry of Culture, but also from EU sources. Other options come into play, as well. We’ve had fine collaborations with the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation and with the ERSTE Foundation[2], for instance. When I’m writing grant applications, I try to think about them in a way that’ll let me include as many different activities as possible, even if they’re not major undertakings. The Singer exhibition is a good example. It’s small, but the scale feels right to me.

Has there ever been an archive that you haven’t taken on, that you recognised as being wanting?

Certainly! Of course there has. The archives in the Arton database are the ones I took on, but the first onslaught and verification happened after the conceptual exhibition I created years ago[3]. Then, working intuitively and wanting some kind of assurance, there were some names that I reached for and some that I didn’t. It seems to me that the artists I’m involved with committed their lives to what they did. Very often, it wasn’t a question of compromising situations. It was, quite simply, a matter of art.

You like that kind of artist… from Kwiek to Singer.

Yes, they’re that kind of artist. In their case, what happened was the dedication of life to art.

The foundation has a gallery where you curate exhibitions and create curatorial programmes. What kind of curator are you?

The exhibitions at the Arton Gallery are small-scale, but they’re significant as far as the foundation’s programme is concerned. The works I choose from the archives are the ones I think are important at a given moment. I do create larger exhibitions, as well, though. Take the exhibition focused on Ludmiła Popiel and Jerzy Fedorowicz that ran from September to November last year. Łukasz Mojsak and I curated it and there were almost a hundred works on show. The scale of the Jurkiewicz exhibition that ran from December to the beginning of February this year was much the same.

You’re warm and open in your dealings with artists and the owners of archives. On the other hand, though, you’re known for not really discussing what you’re going to show in exhibitions or how you’re going to show it.

To be honest, that’s right. If I flick through various negotiations in my mind right now, then yes, that’s really what happens with exhibitions. Then comes the encounter with the artists’ reception. In general, they want to show more. But even when I had more space, at the foundation’s former headquarters at ulica Mińska 25 and ulica Miedziana 11, the selection was still a radical process.

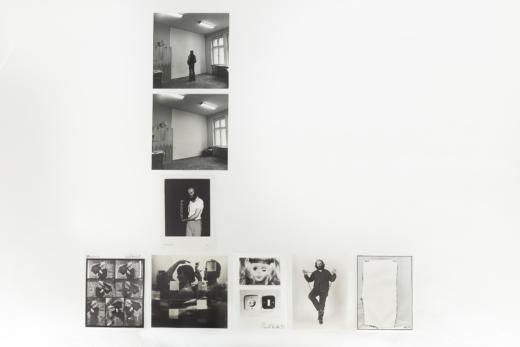

Paweł Kwiek, ‘Różnica czasu’, exhibition view fundacja Arton, November – December 2018

In a sense, you’re creating the artists anew. You’re the person bringing Jadwiga Singer to light and reviving her works.

In Singer’s case, I strove to show more or less all the media that she used. The exhibition included something she adored… screen printing. She was brilliant at it and she loved doing it. There were analytic photographs. There were films it would have been hard not to show. They’re wonderful. But there was also video documentation, because I still haven’t found her broadcasting videos. It was actually a kind of extracted retrospective.

You often show documentation as a work of art. That’s also typical of the art of the nineteen seventies, but it’s something you do in general.

Yes, I like showing documentation.

I think you place a strong emphasis on artists’ subjectivity. Art’s a shifting scene, particularly the art of the nineteen seventies. You hold relatively few of the thematic and group exhibitions that, for example, Łukasz Ronduda, who focuses on that era, excels at. Your artists are also literally present at their exhibitions through their self-portraits and photos…

I once read a piece where a feminist scholar remarked that evoking women artists’ images in the context of their exhibitions is very bad practice because it’s objectification. But I do it intuitively, precisely so as to show their face, because then, behind the image, is the identity. I remember how, when Łukasz Mojsak and I were working on the first Ludmiła Popiel exhibition, I insisted on showing her on the invitation. And I remember how we talked it over and how, in the end, that’s what happened. It wasn’t until a moment later that I realised why I’d done it. I’m a firm believer in biographism and I tend to employ a touch of the biographic method when I’m creating exhibitions, too.

Not fully, though. Because in the descriptions and narratives of the exhibitions, for example, you tend more to avoid it.

Because, on the other hand, I think that, what matters to those people, to the artists, female and male alike, is that their work speaks.

Is that why the art of the nineteen sixties and seventies interests you in particular?

That’s a good question and it’s one that I can’t find a definitive answer to. As I see it, that was an important moment in Polish art. Liberation from the obligation to produce works as objects is something I find very interesting. It seems to me that, in a strange way, I understand those artists and find a common language with them. I understand the realities of that period, of times I neither know nor remember and never experienced. I think it was a moment when artists really did uninhibitedly just ‘do their thing’ and now that can be contextualised in a highly interesting way.

The art you deal with is minimalist and conceptual. These aren’t Łukasz Rondunda’s nineteen seventies, with breasts on book covers and Marek Konieczny’s head with gold foil stuck all over it. This is a kind of sparing art that demands concentration and attention, activities that can’t simply be described as exerting a pull.

The artists I focus on had a need to explain the world to other people. Their works are tools for exploring it. Maybe that’s what it’s about for me? I really love teaching it, as well, because that moment of understanding arrives, when this art that the students initially don’t understand or like begins to resonate with them. There’s a need for art to be useful and, at the same time, for it not to generate large quantities of matter, not to be inordinately absorbing in that respect. It can make demands of the viewer, but it also has plenty to offer them.

Is that why women artists interest you so much? That wasn’t always the case and you initially devoted a great deal of energy to male artists.

The women artists weren’t visible at the start of my journey. It took a few years to see that, between the men, the master ‘technicians’[4], there was someone else. What’s more, it’s undoubtedly my experience of my own functioning in the field of art. I can see that community of experience. I have a sense of community when I talk to Jolanta Marcolla, when I talk to Iwona Lemke-Konart, to Ewa Partum… Our experiences are very similar. For instance, I have the impression that, if I had to stop work for a year or two years or five years, then Arton would disappear without trace in no time at all. That’s the way the cookie crumbles. I can see the same thing applies to these women artists. It’s an inspiring analogy.

Arton’s an organisation and not a woman artist. It’s a bit different.

They also consciously set up their own institutions. Iwona Lemke-Konart ran a gallery. So did Jolanta Marcolla, a small group that was also a gallery…

In your case and Arton’s, isn’t it a kind of feminist statement?

For the best part of a decade now, I’ve believed that what needs establishing are circumstances where these people will have an equal chance of a voice. A new generation of twenty-somethings is emerging and they’ll be looking at the past of art and they’ll have the opportunity of seeing that Józef Robakowski was and that Jolanta Marcolla was. Truth to tell, Józef Robakowski made more films, but Jolanta Marcolla also made some very good ones. Scholars will have the chance to verify and valorise and that’s something they haven’t had so far.

In contrast to women running galleries, like Agnieszka Rayzacher, you avoid connections with feminism… and in contrast to scholars like Agata Jakubowska, you avoid their area of research, women’s art…

I don’t think that any of the people who come to mind at this precise moment… with the possible exception of Iwona, but she has a slightly different, Canadian view of things on account of the fact that she’s been living in Toronto for years now… I don’t think that any of them would want to be assigned to a separate strand of the ‘women’s art’ type. And I don’t only focus on women, either. There was the recent Zdzisław Jurkiewicz exhibition, for instance. And right now, I’m working an exhibition devoted to Jerzy Rosołowicz. Arton isn’t directed solely towards women. There are works by men that interest me and really exert a pull. In parallel with Singer’s archive, I’m working on Grzegorz Zgraja’s. He handed it over it to us. It’s the ongoing development of a picture that’s constantly incomplete.

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, sketches, private archive

Your work at the Arton Foundation very often ends with a documented, digitised and catalogued archive which is then made available on the Internet. After that, are those archives transferred somewhere and stored?

It differs. As far as taking on archives is concerned, I do demur a bit, but they quite simply come to us. That’s a separate matter. It’s happened several times over the past year and we’ll have to consider what form it should take. At the moment, we’re renting a separate storage facility. It’s a good place in terms of the physical conditions, of temperature and light. But it’s expensive.

So it’s a museum-type activity being carried out your foundation?

So it would seem, though that wasn’t the plan. My plan involves taking on the archives for digitising. We also do any essential conservation work, but then we hand the collections back to their owners… only it doesn’t always work like that. It all started with Paweł Kwiek. His archive was stored in an appalling place and it was in a terrible state, so it had to be removed. Similar ‘rescue’ situations occur about twice a year.

As well as all that, you organise conferences and write articles, essays and so forth, not to mention editing and publishing books. Tell me something about how you utilise your work at Arton in your research and your conference and publishing plans.

I’m still producing too few books, but I’m writing as much as I can. It’s a good idea to sum up the work on an archive in a book, though that can take time. Sometimes, there’s a lucky coincidence. Around six years ago, we started working on Jurkiewicz’s archive. I wanted to publish a book, but it didn’t work out at the time. Several years later, the Wrocław Culture and Arts Centre contacted me because they knew about our work on the archive and they asked me if I’d like to collaborate with them on a book. Now I’m planning to publish a series of small books devoted to the artists I’ve exhibited over the past two years.

In addition to the Arton, you not only work with other foundations like the Edward Hartwig, for example, but you also write on other topics, such as performance art, for instance.

Hartwig sprang from what was clearly a really palpable need. I’ve known Edward Hartwig’s daughter for years. Frankly, you could probably call it a friendship. I visit her sometimes and, during one of those visits, we shifted a box of his photos. This was in her modest flat, which was swamped with photographs… they’d had a larger house in the past and then they’d moved and it turned out that there was a mass of material. I said that it would be a good idea to set up an organisation that would look after his oeuvre and that it was really quite odd that steps of that kind hadn’t already been taken. His daughter said that she didn’t know how to go about it alone. Well, and that’s how it started. In November 2019, I opened an exhibition at the Museum of Photography in Krakow and a book will be coming out soon. It’s happened fairly quickly because the Hartwig Foundation succeeded in getting a two-year grant for the exhibition and book. The book won’t be an all-inclusive monograph on the topic, but it will convey a picture of what Hartwig’s art was, in its full, sweeping extent, from start to finish.

Yet, in comparison with what we were talking about earlier, Hartwig’s a completely different choice.

It’s a different choice, but I like situations that are ambiguous and far more profound than they seem. Hartwig’s that kind of ambiguous artist. He’s been ‘tagged’ with a handful of fairly banal formulae and left to his own devices. I don’t accept that. It’s much the same with the archive and works of two sisters, Alicja and Bożena Wahl. For various reasons they’ve more or less ceased to function in today’s art world.

view of the repository www.forgottenheritage.eu

Out of sheer contrariness, you want to take things that have been tagged as uninteresting, mediocre or even backward, and interpret them anew?

Yes, definitely. Hartwig is a well-known name that still doesn’t actually say anything to anyone. What’s at work in our heads are clichés, mere shadows of an inkling and opinions about him. What I’m doing is a bit the same as for the artists who just about no one knows about. It’s different, but similar. I’m not capable of focusing on something that everyone wants to focus on. It would be too easy.

Talk to me about performance art. There’s a book you’ve been working on for several years and it’s due out any moment now. What is performance art to you, where does it spring from and how do you define it?

My work on the book unquestionably sprang from reflecting on the nineteen seventies. We think about performance art in Poland as a medium that crystallised at precisely that time. The way I started working on the book was to carry out interviews with performance artists, men and women alike, who were working then. I began by asking them about their sources of inspiration, which were sometimes worlds apart. Such was the case with Zbigniew Warpechowski, with Tomasz Sikorski, with Janusza Bałdygi… Those sources of inspiration pointed the way to some really interesting trails. Basically, following those trails took me back to the nineteen twenties. That part of my research turned out to be even more interesting than my starting point as a topic for description… in other words, things that I really wasn’t so familiar with… the early Cricot years, Kantor’s early works. To me, Kantor is a stupendous challenge. There’s this element to him, whereby he’s continually being rediscovered, yet there are so many things that art historians still haven’t encompassed. When I was working on the book and trying to chart the turning point, that’s exactly where I wound up. I was seeking the moments that were in some way proto-performance art, where, even if that name hadn’t yet been applied, there was an awareness of process, where attention was paid to the process and a conscious abandonment of artwork.

How does your definition of the field of performance art differ from Amy Bryzgel’s or those of Polish theorists like Łukasz Guzek? Do you apply a more theatrological approach?

Yes, I think so. Roselee Goldberg’s concept is probably the most akin to mine… on the one hand, theatre emerging from theatre but, on the other hand, in terms of history of art, the abandonment of the object. As far as Łukasz Guzek is concerned, we differ profoundly because he starts from the conviction that performance art is something which grew from the soil of visual art and is an autonomous medium. I don’t fully agree with that because I see all sorts of infiltration in it, for instance, in the moment when we reach the Wrocław scene, where Grotowski’s theatre crystallised, but there, too, it began earlier and I have the impression that it wasn’t for nothing that he wound up precisely there. It’s already very dense and, frankly speaking, I can’t see the sense of creating an ‘essence of the performative’. To me, it’s a question of the greater the infiltration, the finer it is.

You’re well-known in this part of the world thanks to networking and the conferences you organise.

The conferences are the result of a desire to explore what’s going on in the world around us. We don’t know much about art in neighbouring countries. It’s a bit like the way we don’t know much about what was happening in Poland in the nineteen seventies… and we know even less about what was happening in Czechoslovakia at the time. To me, it’s a natural direction to take. I have the feeling that, once I’ve developed and worked on a topic here, then I have to keep widening the circle and kind of tread out an area of exploration that’s beyond the borders, but around us and not a long way away. It’ll be a challenge, of course, when it comes to Ukraine… Quite recently, in Brussels, during the launch of a women’s project, I met a curator from Finland, from Helsinki, and she was also working on a very interesting project entitled Artists at Risk. They bring in artists from countries where there’s conflict and try to arrange for them to stay with families in Finland. But she’d been doing a huge amount of research in Russia, delving into the art of the nineteen seventies and she’d discovered some massive private archives of conceptual art in Saint Petersburg and in Moscow. We started thinking about how it would be possible to get access to them and explore them.

The formula for the Arton Foundation and your activities is very international, so will the book also be coming out in English?

Yes. I start with the assumption that, if I’ll gladly read a book on performance art in Czechoslovakia, then there’s every likelihood that someone in the Czech Republic or Slovakia will gladly read a book about Polish performance art. All it takes is a bit of networking, ten people, for an interesting exchange to emerge and, perhaps, something that will make it possible to re-evaluate that particular aspect of the art scene. When I was in Brussels for the launch of the women’s project, there was a one-to-one meeting and the officer looking after our part of it said that it’s one of the six or seven most important undertakings and that we have the tools to carry out a powerful and profound redefinition of the art in this region of Europe… and that they’re waiting for us to do that. They’re not expecting us simply to add successive works to the database, but to actually work on how it’s being received, so as to make it something that’ll be viewed.

What’s the project?

In brief, it’s concerned with discovering women’s archives and making them accessible. Our particular project is focused on Poland, Slovenia, the former Yugoslavia, primarily Croatia, and Latvia. Our previous partners were Estonia, Belgium and, again, Croatia.

Will you be showing Arton’s archives?

I’ll be showing Arton’s archive and graduation works from the archives of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Art. The dream situation would be that the students taking part in the workshops run as part of the project start searching through the academy’s archive and each of them finds something that’ll be the start of a skein for them and they’ll give it a tug and follow it and maybe find something that turns out to be extraordinarily valuable.

You’re working at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts now. Every time I talk to you, I can hear how devoted you are to your students and to teaching…

It’s a highly rewarding field and it suits me. I’m lucky in my students because they’re extremely committed, they’re eager to work and gladly take part in the foundation’s activities. Teaching and my work at Arton make an excellent combination. I find myself having less and less time, but the students have the chance of putting some of the theoretical stuff into practice and it works.

If I’ve understood the project you’ve been talking about, it combines your activities at the foundation with your work on the archive at the Academy of Fine Arts?

Yes. It’s an EU project and part of it will be classes held in the archive. The idea is that it will end with a joint exhibition.

The specific nature of your work involves oscillating between working with private archives that are languishing in attics, waiting to be discovered, and well-reconnoitred institutional archives flipped through by the dozen by large state institutions.

Yes, that’s another archival challenge that I’m trying to take on.

Translated from the Polish by Caryl Swift

[1] http://repozytorium.fundacjaarton.pl/, https://www.forgottenheritage.eu/artists – ed.

[2] Now KONTAKT, the Erste Group and ERSTE Foundation Art Collection – ed.

[3] In 2010 – ed.

[4] The members of the Warsztat Formy Filmowey / Film Form Workshop, an avant-garde group founded by students and graduates of the Łódź Film School – ed.