Adam Mazur: What are you doing in Munich and what is the Public Art Munich project exactly about?

Joanna Warsza: I am the artistic director of Public Art Munich 2018, which takes place every few years in the public space of Munich. About two years ago, in 2016, I received an invitation from the city’s culture department to take part in a closed competition for the second edition of PAM. Many cities build their prestige, or image through art, and I think that this kind of attitude is also successful in case of Munich. I did not expect to receive such an invitation from the Bavarian capital. However, it was not a city that I chose, in a sense the city chose me. Four curators were invited for quick research, consisting of a three-day introduction to Munich and on this basis a proposal for a project had to be written. My first association was typical for many other people of our age from this part of Europe, namely it referred to Radio Free Europe. It was Munich’s voice coming from behind the Iron Curtain. Earlier, I was here only once, when we attended a lecture of Artur Żmijewski in 2012 at the local Academy of Fine Arts. Being here again, I visited these RFE buildings, which had been abandoned by the Americans and editorial offices in the early 90s. I have found out that there were not many traces of the Cold War era. Then I invited Lawrence Abu Hamdan from Forensic Architecture for cooperation, which made me realize that there were actually more connections than I thought. Nowadays, former radio studios house the library of the media, politics and communication department. If today you are studying ideology, propaganda, counter-propaganda, you have to spend a lot of time reading books in the studio from which RFE broadcasted to Romania, Czechoslovakia, Poland and beyond. You have to be quiet in the radio studio and in the library. Lawrence noticed that it is the sound of silence that combined these two stories. His project refers to sound leaks in the political sense. One of the main slogans of Radio Free Europe was: “The Iron Curtain is not Soundproof.”. The lecture by Stefanie Peter will also focus on this issue.

Does PAM deal with various ideological changes?

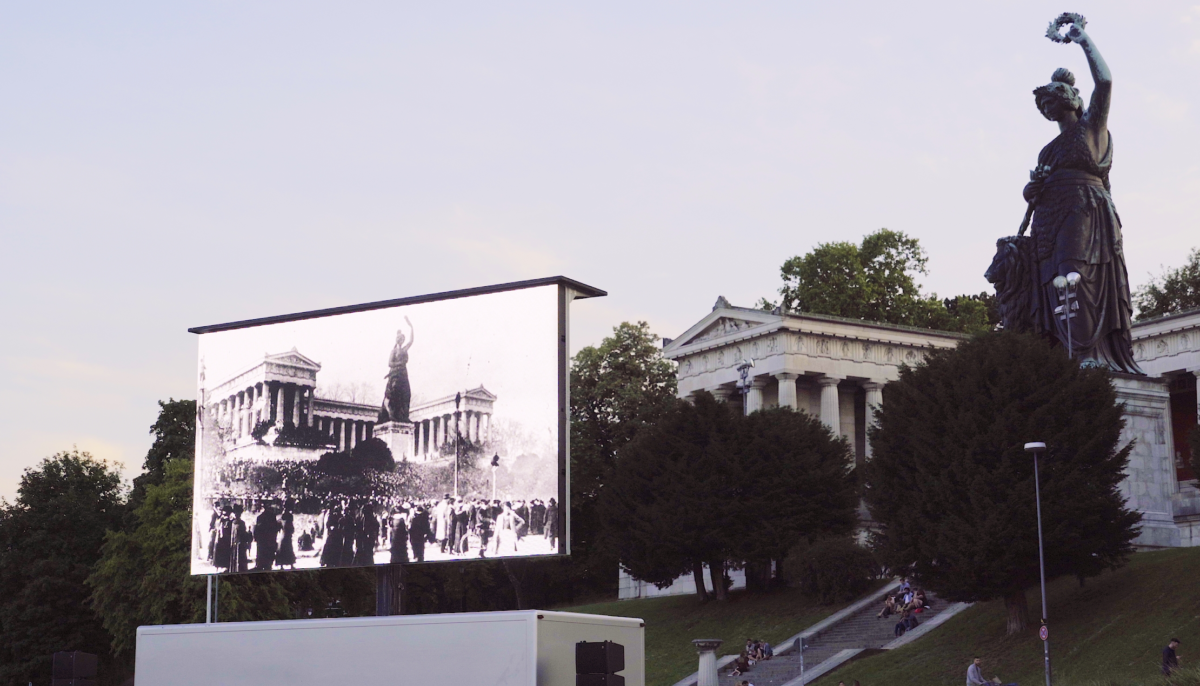

I am interested in how ideology transformes, which makes us review our point of view and focus on how we become part of this change. The radio helped me build the whole curatorial concept. There are not many cities where ideological and political changes are as diversified as in Munich, which today is a rich, still western, hedonistic city with a high standard of living. At the same time, during walks around the city you pass places where Hitler marched with the putschists and where the Crystal Night began. But then you see more layers: here also the Soviet Bavarian Republic was established, it was founded mainly by writers and artists such as: Oskar Maria Graf, Ernst Toller, Erich Mühsam and others. The policy of the city underwent ideological transformation from the extreme left to the far right, during a few years. I was interested in what was the reason of these changes? And how different is this city today than it was after the Second World War, it was at the Munich train station in autumn 2015 where the symbolic admission of refugees took place.

At the same time, your PAM program is not focused on history, but on the present day…

PAM deals with ideological fractures and ideological transformations. I am interested in these policy changes like the declaration of the Soviet Bavarian Republic in 1919, the invasion of the Allies and the construction of Amerikahaus, the beginning of denazification, the establishment of Radio Free Europe, the construction of the stadium and the inauguration of the Olympic Games in Munich in 1972, or the admission of refugees to the Hauptbanhof and the beginning of the Willkommen Kultur in 2015. Although crucial moments lasted only a few hours, they had lasting and significant consequences. I am interested in their ephemeral, symbolic and their political significance. By public art, I mean those public moments arranged by artists – meetings, marches, processions, matches or congresses. The place where we are now talking, Bellevue di Monaco, is located on one of the most expensive Munich streets. Despite the speculation on the real estate market, it has been legally taken away from the developers and has become a refugee center, a place for consulting and meetings. Significantly it’s name sounds like the name of a five-star hotel. The name ‘Monaco’ means ‘Munich’ in Italian, the fact that this place is successfully functioning here indicates the idiosyncrasies of Munich: prosperity, civic engagement and a bit of anarchism and unpredictability in one.

My first association was typical for many other people of our age from this part of Europe, namely it referred to Radio Free Europe. It was Munich’s voice coming from behind the Iron Curtain.

What therefore does this change consist in?

The most crucial moments from my point of view are those moments of history that define ideologically an aura and show the way how society develops. Therefore my proposal assumed a series of ephemeral performance projects, avoiding to resort to old, cliched idea of presenting sculptures in public space.

The PAM title is Game Changers, can you explain this further?

JW: Game Changers are the moments when there is a symbolic and ideological change, it is also a quote from the language of neoliberalism and event economy. We are all part of it, instead of avoiding it, it can be appropriated and transformed. When it comes to art I am less interested in an object or sculpture, and more in a lively situation.

How did you choose artists for PAM?

As a curator, I often start working on a specific topic or problem as a starting point. I am interested in topics related to the burning issues of our time, of course especially those which are somehow related to this city. However I was given complete artistic freedom and it was a great foundation for action, especially when you know what these issues look like in Poland, Hungary or other places that are leaning ideologically to the right today. Here, in a sense, I’ve become a curator of Munich. What do you do when you are an architect of the city? You are getting involved in its problems. I see my role in a similar way, but the main area of my activity is art and I never make compromises for that matter. Many places and topics have been proposed by artists, such as invisibility of knowledge of immigrants, a topic proposed by Canay Bilir-Meier, who is also an active observer of the NSU process that has been taking place in Munich for several years. In this process, the knowledge of victims’ and migrants’ families was very often not taken into account. Cana transferred these observations to the mosque located in the Freimann district, where her project took place. If you google this mosque, the first 10-20 results are about CIA, Muslim Brotherhood etc. Yet, there is also a completely different and unwritten history of this place, connected with the community or modern Islamic architecture. This place seemed to us to be very ideologically and socially burdened and therefore worth to be approached in a new way. Cana Bilir-Meier wrote a different story of this place, finding and bringing back the cornerstone which was actually never laid there.

Some of the artists invited to PAM have been working with you for many years. For example, Massimo Furlan or Aleksandra Wasilkowska. Some of them are Munich artists that you have not worked with before. When negotiating the conditions of employment as a city curator, did you agree with them that you are going to present a local artistic scene as well?

I was not required to do so, yet because you hear from many people that there are no interesting artists in Munich, I really wanted to check it out and as a result 1/3 of projects are created in cooperation with Bavarian artists such as: Alexander Kluge, Michael Mélian, Cana Bilir- Meier, Flaka Haliti, Franz Wanner, Leon Eixenberger and Olaf Nicolai, who is strongly connected with the city. Munich has a lot of different museums: Pinacothecas or Haus der Kunst. And presents even more art than it is able to bear. However, this is a BIG art. In this context, as someone told me, Public Art Munich allows for taking a deep breath. On the other hand, it’s hard to be surprised by the outflow of artists. Life costs are 2-3 times higher here. In a sense, Munich is earning for Berlin. Here at 10:00 pm everyone is in their beds, the city falls asleep to be able to wake up early and go to work in the morning. Simply put, Berlin is partying at the cost of Munich, that’s how the federal ‘fair’ distribution of costs and taxes looks like. However, there are no separatist tendencies.

If you act in public space, then “you have to mean it”. You really have to ask yourself: what does it mean? Who is your audience? What does art outside the gallery walls mean? What do you mean by mediation and the public sphere? How to create a public debate?

PAM cooperates with municipal institutions – although not with Pinacothecas – consequently not accepting the form of the exhibition …

I’m trying to approach the task I was given here seriously. Maybe I even look at it in a way that is too social-democratic way. If you act in public space, then “you have to mean it”. You really have to ask yourself: what does it mean? Who is your audience? What does art outside the gallery walls mean? What do you mean by mediation and the public sphere? How to create a public debate? How is private space today confronted with the political one? What is the economy of experience? What is immaterial art? I am also interested in the problem of the loss of the institution’s protection. When you enter Haus der Kunst, you do not ask yourself if there is art inside. You come to the stadium for the match (eg a match of FC Bayern youth clubs directed by Alexandra Pirici and Jonas Lund at the Allianz Arena) and there you’ll find art. This is a very interesting moment when art has to defend itself and test its real potential, which it often dreams about. In a lot of curatorial statements, you read about an attempt to reach a wider audience, diversity, multiplicity, but is this really happening? Museums do what they can: more and more mediation, education, but when you are outside the institution, you have no choice, many people will ask confusedly: “Is this art? And why? ”

If you were to indicate a project that would be most important for you, as a curatorial challenge, the one that would also indicate what is happening in Munich, and which would be the core of the PAM – what would it be?

The opening in the Olympiapark was a significant undertaking and a serious event. We started with the project by Ola Wasilkowska, who found a very interesting example of shadow architecture: a project of illegal church, made out of cardboard, which was created on the grounds of the Olympiapark before the creation of the Stadium, still in the 1950s on the ruins of the city (similarly to the 10th-anniversary Stadium in Warsaw where I worked in 2007-2008). The ceiling of this Ost-West Friedenkirche is glued with aluminum silver paper and resembles a rippling roof. Apparently, architects Otto Frei and Günter Behnisch were not only inspired by this little temple, but they also changed the whole master plan to save it, although it did not formally exist. Ola managed to present in a very poetic way how this knowledge is stored in the Olympic roof. Her mobile, living ceiling installed in the church was also a tribute to the spiritual anarchism that is strongly present in this city. As the writer Thomas Meinecke says: Bavaria is inhabited by anarchists who only occasionally vote for the CDU.

From the church, the procession led us to a match at the Olympic Stadium. It was the work of Massimo Furlan, with whom I worked ten years ago in Warsaw, to make the reconstruction the Poland-Belgium 1982 Match. I wanted to start PAM at the Olympic stadium, in a place associated with optimism, democracy, post-war purification of Germany of nazism, a new chapter for Munich. We also know, of course, the tragic history of this place, but we did not refer to it. I invited again Massimo Furlan, who offered to make the reconstruction of the Cold War match between NRD-DDR 1974, which result was 1: 0 for NDR, against everyone’s expectations. This match was not important from the point of view of football history – both teams were already qualified for the next round – but it was an extremely interesting cultural and cold war meeting. Massimo Furlan made the reconstruction of the choreography of Sepp Maier, a West German goalkeeper, and Franz Beil, an actor from Volksbühne of Castorf and Pollesch, played Jürgen Sprawasser, an attacker from East Germany. The audience could listen to two independent radio commentaries, East and West German, which constituted two versions of alternative reality of that time.

There was an accident during Furlan’s performance. The actor who played Sparwasser, who scored a goal for the GDR, broke his ankle and had to leave the playing field and was ultimately taken to the hospital, which was not planned. As you can see, this is another example of unexpected change of the rules of the game referring to the PAM edition’s title – Game Changers.

I do not think I’ve ever been as stressed as at the time of the accident. However, after a while I realized that the audience decided that “the show must go on”, which made the match become even more abstract and the situation even more radical.

In a sense, Munich is earning for Berlin. Here at 10:00 pm everyone is in their beds, the city falls asleep to be able to wake up early and go to work in the morning. Simply put, Berlin is partying at the cost of Munich, that’s how the federal ‘fair’ distribution of costs and taxes looks like.

When choosing the best opening, you opted for the match between the GDR and FRG, and not, for example, the attack on Israeli athletes.

Though it is only art, there are is similarities, the one referred to the fact that something broke, failed, or has taken a completely different course. I find the moment when this fiction breaks very important: the player is injured and suddenly there appear meta-questions about what performance is, what is the preparation, how the imagination works, how the confusion works, for how long you see the event as a fiction, and when it suddenly becomes true… What is it actually about?

Jérome Bêl, a choreographer, posed significant question during his performative lectures: why an actor who is making mistakes causes a greater commotion among viewers than one that plays his role impeccably? It’s because in the second case you experience the moment when fiction is transformed into reality. If you act in public space and do performances, you have to be prepared for it, you need to know how to integrate what is unpredictable and how to be ready to change the course of events.

In your opinion, art can display the problems of modern times and somehow diagnose them?

We, people of art, are critical individuals who often expect art to have certain strength, causative power, creative force, to create a space for a different view of the world. There is no better place than the public sphere, which can be place of confrontation of those who came to see the artist’s project and those who always resisted it.

Imprint

| Artist | Aleksandra Wasilkowska, Alexander Kluge, Alexandra Pirici & Jonas Lund, Anders Eiebakke, Anna McCarthy & Gabi Blum, Ari Benjamin Meyers, Cana Bilir-Meier, Dan Perjovschi, Flaka Haliti & Markus Miessen, Franz Wanner, Jonas Lund, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Leon Eixenberger, Mariam Ghani, Massimo Furlan, Michaela Melián, Olaf Nicolai, Rudolf Herz & Julia Wahren, Students of the Academy of Fine Arts Munich, The 9th Futurological Congress / Julieta Aranda & Mareike Dittmer |

| Exhibition | Public Art Munich 2018 |

| Place / venue | Munich, Germany |

| Dates | April 30 – July 27, 2018 |

| Curated by | Joanna Warsza |

| Website | pam2018.de/ |

| Index | Aleksandra Wasilkowska Alexander Kluge Alexandra Pirici & Jonas Lund Anders Eiebakke Anna McCarthy & Gabi Blum Ari Benjamin Meyers Cana Bilir-Meier Dan Perjovschi Flaka Haliti & Markus Miessen Franz Wanner Joanna Warsza Jonas Lund Lawrence Abu Hamdan Leon Eixenberger Mariam Ghani Massimo Furlan Michaela Melián Olaf Nicolai Public Art Munich Rudolf Herz & Julia Wahren Students of the Academy of Fine Arts Munich The 9th Futurological Congress / Julieta Aranda & Mareike Dittmer |