It was an interesting coincidence to encounter two specific exhibitions in Warsaw: Neighbours and Waiting for Another Coming, as both of their starting point was Poland’s relationship with a neighbouring country. Yet, the two shows – Neighbours curated by the Kyiv based collective Visual Culture Research Center and the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw in the framework of the Warsaw Under Construction festival and Waiting for Another Coming at Ujazdowski Castle Center for Contemporary Art – couldn’t be more different. The notion “neighbour” appeared in two very different contexts: on one hand, in Waiting… it was literally about presenting works both from Poland and Lithuania but somehow couldn’t address the real ongoing relationship between the two neighbouring countries. On the other hand, Neighbours curatorial concept was precisely to shed light on the more and more visible Polish-Ukrainian relationship (eg.: Ukrainian guest workers arriving to Poland), and through that, talk about the issues of migration, precarious working conditions and the constant dilemma what does it mean to live in a post-socialist world. The goal was, as the curators summarized in the press text, to “capture the picture of today’s neighbourly relations and the meanings taking shape around it through the Warsaw and Kyiv link as an example of broader, global processes that can be identified amid the ongoing migration between the two cities.”

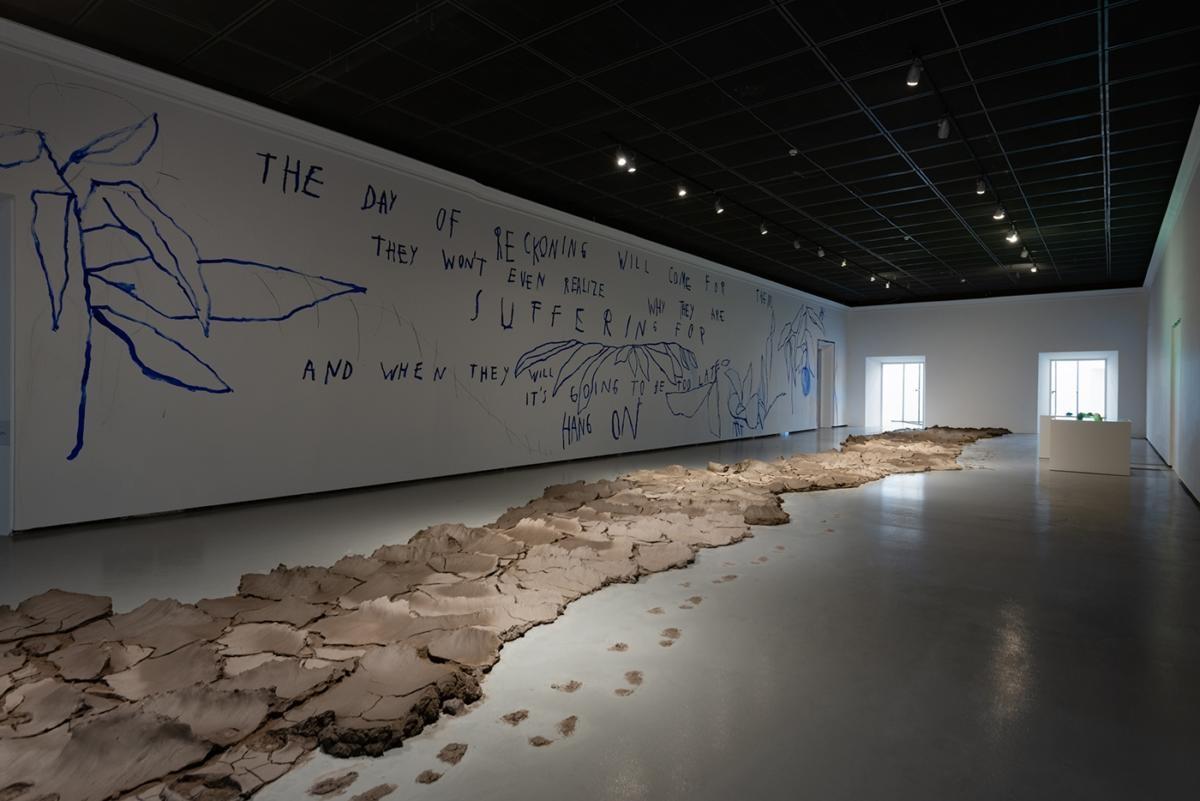

Waiting for Another Coming, exhibition view. Photo: Bartosz Górka could be considered as the more white-cube-esque, work-concentrated exhibition from the two. The long and elaborated curatorial text took Michael Foucault’s notion of heterotopia as its starting point and combined it with the question what utopia means today. As the text said: “rather than constructing utopias, they (the works) focus on specific heterotopias – whether actual, virtual or imaginary”. The invited artists – who often contributed with new works, – were supposed to “imagine” future scenarios based on our problematic present. However, this was barely visible in the works and there was a certain kind of gap between the curatorial concept and the artworks themselves. Some of them touched upon sensitively on local stories both from Poland and Lithuania – like Lina Lapelytė’s Ladies or Małgorzata Goliszewska’s Twin Sisters project – but the exhibition remained rather fragmentary. The often very high quality projects functioned as “mini solo shows” and they didn’t really connect with each other. It was interesting in a way to learn about the most characteristic artistic strategies from both countries (according to the curators), but as the relationship between Poland and Lithuania is a bit alienated, so were the different artworks. Waiting for Another Coming as its title suggests, is a very poetic exhibition, which touches upon important notions of belonging, believing, collectivity, temporality, yet as an exhibition it has difficulties with reaching its audience.

I can’t avoid the idea that exhibitions like Waiting for Another Coming often tend to stay in a hidden nationalistic framework, despite the fact that some works argue especially against these notions.

One could also wonder why these kind of exhibitions were prepared – because of some collaboration between the institutions or the fact that it is relatively easy to get funding for these travelling “pair” shows which are focusing on and comparing the most relevant artistic practices from the selected countries? Even though I haven’t seen the other part of the exhibitions in Vilnius, I can’t avoid the idea that these kind of exhibitions often tend to stay in a hidden nationalistic framework, despite the fact that some works argue especially against these notions.

Visiting the Neighbours exhibition one could have a completely different feeling then Waiting..: because of the venue – which I will later get back to – but also because of the strong artist-activist content, it was a heated show, which could even encourage the viewer to move out from simple contemplation and take responsibility in some way. Yet the socially-engaged artistic practices were combined with more classical approaches and the exhibition neither fall into the trap of agitation, nor did it lose its aesthetic guidelines. From the combination of various artists, a diverse constellation has been unfolded. The exhibition chose its artists list carefully, and presented well the Polish, Ukrainian artists (who are more or less well-known in the local scene) together with internationally more “famous” ones, like Hito Steyerl or Phil Collins. Despite the fact that some of the more celebrated artist’s works functioned as highlights of the show, there was a balance between these different oeuvres.

Neighbours was initiated by the Warsaw Under Construcion festival (10th edition) and was curated by the Ukrainian collective VCRC (Anna Kravets, Yustyna Kravchuk, Oleksii Radynskyi, Ruslana Koziienko, Serhiy Klymko, Vasyl Cherepanyn, Nataliia Neshevets, Oksana Briukhovetska, Ganna Tsyba) together with curator from the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Szymon Maliborski. It is important to mention a few words about VCRC: it was founded in 2008 and it is a platform for collaboration between academic, artistic and activist communities. Since its foundation, VCRC curated several exhibitions, organized public lectures, talks and discussion and took part in research programs. They were also organizing The School of Kyiv – Kyiv Biennial 2015 and The Kyiv International – Kyiv Biennial 2017 which is considered to be one of the most important events in the region.

As the collective of VCRC summarized in their curatorial concept, their starting point was the “usual” experience to live side by side to each other, but which experience gained a new context recently by the arrival of season workers and other migrating people as well as their everyday life practices. This is why the latest edition of the festival examined the idea of neighbourly relations in our shared environments, but which relation is characterized by the constantly changing geopolitical and social circumstances. The huge curatorial collective took care of a likewise huge and complex show. Its title and concept reminded me of Universal Hospitality, an exhibition presented first in Vienna in the framework of Wiener Festwochen (2016), then in Prague (Futura, 2017), curated by Edit András, Ilona Németh, Birgit Lurz and Wolfgang Schlag. That exhibition which dealt with the notion of migration in our new geopolitical conditions took Derrida’s notion of absolute or radical hospitality as its starting point which could be also useful when analyzing Neighbours. The curators of Universal Hospitality found important this notion (and Derrida’s readings on Kant) as it offers an alternative, broader concept of hospitality, which opens up the possibility to welcome everyone, all human beings, including total strangers. This very open and inclusive strategy could link also to the relationship with our neighbours: people who are often strangers but are in need for hospitality in their (new) environments. The Neighbours exhibition like Universal Hospitality, presented artistic strategies which are offering critical, ironic, self-reflective and emphatic ways about how to live together with others and how to understand better our present circumstances. A smart curatorial gesture was to talk about these issues of migration not as a “random” happening but within a context: through the questions and problems raising from living situations, housing problems, the conditions of guest workers and the architectural structure of the city. It is of course obvious, how these themes and problems are linked to the question of migration and the refugee crisis, but as the exhibition presented different local perspectives and micro narratives, it managed to shed light on these questions from a different point of view. This made the whole exhibitions very refreshing. The only thing I missed is the aspect of collaboration: it would have been interesting to see more projects in which – for example – Polish and Ukrainian artists would have worked together.

The weird orange modernist building of the so-called Cepelia pavilion in the center of Warsaw functioned as a great location. The building was originally constructed for the Central Bureau for Folk and Artistic Industry in the 50’s as an exhibition space with two floors where they sold and presented handicrafts and other folk related artifacts. It is not surprising that after 1989 the building changed its functions a lot, (it was a travel agency and a few years ago a casino for example) and lately its façade transformed too: a huge LED screen were adjusted to it, signaling ironically the amount of public debt, for example. When in 2017 the Bureau for Folk and Artistic Industry went into liquidation the building got into private ownership. For the Warsaw Under Construction festival it is well-chosen location and luckily, the building is not used only as a stage décor but it’s changing history serves as a kind of backdrop for the exhibition. Through this specific “case study” several themes of the exhibition could come up, like the situation of the “forgotten” modernist architectural heritage, the ownership of places and the housing problems of guest workers.

The weird orange modernist building of the so-called Cepelia pavilion in the center of Warsaw functioned as a great location. The building was originally constructed for the Central Bureau for Folk and Artistic Industry in the 50’s as an exhibition space with two floors where they sold and presented handicrafts and other folk related artifacts.

As we enter the building we find ourselves in a different universe. The red carpets, mirrors and the whole interior has a “retro” atmosphere, like we traveled back in time, into the 60s. But the artworks quickly pull us back to the present. The first work by Oksana Briukhovetska (artist, curator from VCRC) which is even visible from the outside is a large orange-blue (striped) mural, with the colors of both national flags – Polish (white-red) and Ukrainian (blue-yellow) – melting together. A provocative sentence is written on the “enlarged” fictional flag: “Has not died yet”. It turns out, that the sentence is a fragment, which appears in both national anthems. While listening to the various interviews with different inhabitants of Warsaw presented in the same space, a chain of association could start from the strange sentence: if we did not die yet, what should we do? What should we preserve, what should we remember, how to fight, how to look for alternative solutions in our lives? The exhibition in a way tries to answer these questions, but in the end we just face more questions, and often regarding issues we tend to hide or repress.

According to the curatorial text, the exhibition is divided in different chapters which are: Neighbours in the Workplace, On Conflict, Battle Over Memory, Legacy of Soviet Architecture. I only found these subthemes on the website, but nevertheless, it was quite clear what are the different questions and problems the exhibition tackles. The chapters are interconnected and they dissolve into each other, yet the exhibition is not overwhelming in a negative sense, as the show has a clear and easy-to-follow dramaturgy and plan. One of the strongest group of works are the ones which are dealing with the situation of guest workers, their housing problems and the difficult living conditions they face. This is that side of the show which reflects directly on the Polish-Ukrainian relationship too. Ukrainian artist, Taras Kamenoy’s installation (Trestle-dwelling and Modular Furniture, 2014-15) deals with the poor living conditions of construction workers who often live where they are working. Kamenoy creates a preliminary dwelling place inside Cepelia, where it is not clear, if its possible for the viewer to sit and rest or to build something out of it. The installation has momentary character, something which is in-between, like the situation workers often live. Right next to this piece one can listen to the striking documentation by Crisis TV (Antoni Wiesztort) (No title – Agency, 2017) a Polish artist-activist group whose activist took up the roles of businessman and called employment agencies asking for cheap labor in Poland. In the video we listen to the telephone conversation in which the artist tries every way to give as small salary as possible to the workers and go to the extremes concerning their basic rights. The agencies go with the flow and it seems that the system is working quite “well”. TV Kryzys is precisely that kind of artist-activist project which infiltrates the system and through such an easy “act” highlights those everyday injustices we often forget.

Another important piece in the context of working rights is the collaborative project by Oksana Briukhovetska, Kseniya Hnylytska, Valentyna Petrova and Davyd Chychkan, titled I Am Ukrainka (2018). It consists of a series of posters, which appear not only in the Cepelia building but one can find it through the whole city of Warsaw. The posters depict Ukrainian migrant women workers in Poland (each of the artists draw one portrait), doing low-payed, often humiliating jobs (cleaning lady, dishwasher) which is also stereotypical if one thinks about what kind of jobs migrants, especially women do. Through the posters suddenly the women and their often side swept job become visible and shed light on the unfair economic situation which the neoliberal society imposes on us. On the background of the posters one can recognize Lesya Ukrainka, a poet and feminist activist from the early 20th century: in a way she encourages these women on the posters to stand for their rights and also force us, to look at these working conditions and don’t turn our heads away.

Further works examine the notion of home and seeking shelter in our present day. Ukrainian artist Nikita Kadan deals with these questions from a different perspective as he researches past traumas still effecting the present (Everybody Wants to Live by the Sea, 2014-16). The artist focuses on the 1944 deportation of the Crimean Tatars. In his delicate photographs, Kadan documents the self-built settlements of those who returned to their homeland after 1989. The unstable structures – which are often left unfinished or ruined by local authorities – could suggest how fragile is our sense of belonging and whether if it’s still possible today, to find a place which we can call a home. The geometrical shapes drawn over the documentary style photographs resemble soviet modernist architecture, which was built on the same territory, after the ethnic cleansing. Kadan juxtaposes different historical layers and temporalities and emphasizes how past atrocities still have traces in the present.

With Oleksiy Bykov’s project (Museum of Architecture, 2018) we move towards the before mentioned question of soviet modernist heritage: the artist researches the archival traces of post-war modernist movements in Ukraine, and the most interesting aspect of his work is a documentary film-in-progress about the famous “UFO” building in Kyiv. The flying saucer is only the nickname of the building, as it was originally the Institute of Information, built in 1971 and designed by Florian Yuriev. The film, made by Oleksiy Radynski, tells the story of the buildings before-mentioned architect, Yuriev and how together, with the so-called Save Kyviv Modernism movement people tried to stop the new development which meant to create a shopping mall and merge the building within that. In the sensible documentary we see how the 89-year-old architect even created his own architectural proposal to change the development and through that we learn about his visions about city planning. Later it is almost heartbreaking to see the building being completely emptied out and as the process is still ongoing, there is no relief at the end of the film. The project not only raises the question about how to deal with the Soviet modernist heritage but shows emphatically the struggle of different people, connected in a new kind of solidarity. It is also important to mention Oleksiy Bykov’s fictional museum as part of this project, in which installation (tabloid) he presents the influences and artistic visions of Yuriev put in the context of his architectural research on modernist buildings.

As so many artists deal with the ambiguity of memory and the process of oblivion it is rare to encounter unknown or eye-opening critical approaches in this field. For me it was an important revelation of this exhibition that the works in the Battle over memory section addressed these problems from an unusual perspective. Shards (2013-14) by Mykola Ridny and Serhij Popov (both from Ukraine) juxtaposed the story of two plaque /sculpture demolitions – real, physical battles actually – whose ideological background was quite different. We can see documentations on tablets about the demolition of the pedestal of a previously torn down statue of Lenin in 2013 in Kyiv and also in 2013 the destruction of a commemoration plague of Ukrainian scholar Yuri Shevelev. A campaign was initiated against the above-mentioned plaque by the pro-Russian government of Kharkiv, because Shevelev was accused of collaborating with the Nazis in the Second World War – the result was the demolition of the plaque by an unknown group of strangers. On a huge pedestal the shards of this plaque which were found and retrieved by the artists were presented together with the baton which was used to destroy the pedestal of the Lenin sculpture. The found objects (ironically those pieces which passer-byers received from the Lenin statue were not here) and the gesture of appropriation had a strong statement in their minimalism: the objects stood as silent witnesses of the process of commemoration and how the procedure of what a nation wants to remember or not, changes constantly.

The installation worked quite well with the delicate drawings of David Chychkan (Triptych of Decommunization, 2017), displayed on the opposite wall. In his series the artist depicts the statues of emblematic Ukrainian leftist intellectuals – poets Lesya Ukrainka (mentioned before), Ivan Franko, and scholar Mykhailo Dragomanov – whose memory and legacy is erased by the process of “de-communization”, mostly practiced by the far-right. The process of oblivion is emphasized by the material itself – the drawings look as if they are fading away, yet the different sizes and various forms which appear on the paper shed light on the constantly changing perspectives concerning these figures. It is important to mention that the works on display have themselves been damaged by far-right vandals during their attack against Chychkan’s exhibition at VCRC in Kyiv, 2017.

The exhibition manages to talk about the refugee crisis and the migration politics in a surprisingly non-cliché way.

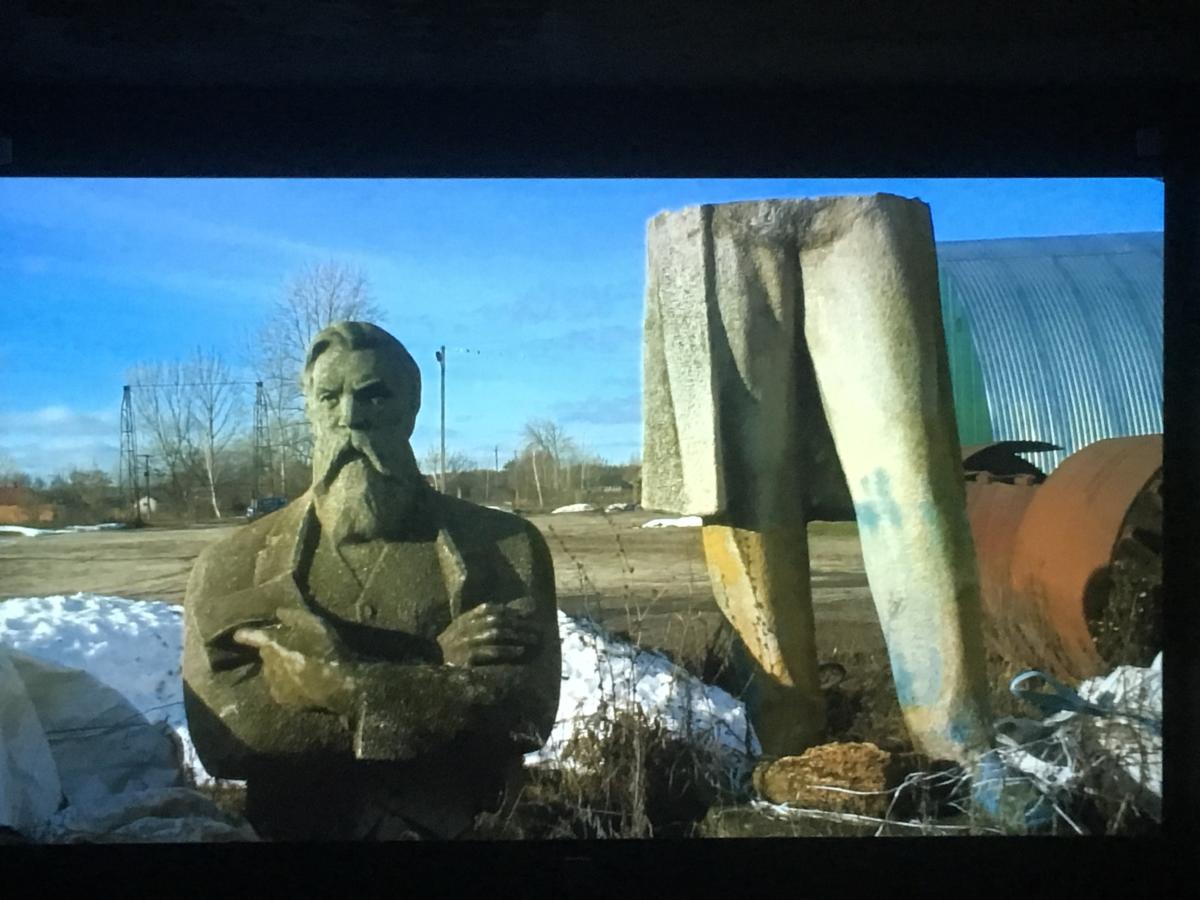

And to mention one of the “international superstars” of the show: one could argue whether it is a good idea to present the English artist, Phil Collins’s 60-minute-long film, Ceremony (2017) about the “road trip” of an old statue of Friedrich Engels from a Ukrainian village to Manchester, in a group show. Nevertheless, it was really worth to go back, and watch the film on a separate occasion: the road movie carefully connects leftist heritage with the current British social movements yet uses a lot of irony, while showing the voyage of the Engels sculpture throughout Europe finally finding its place on Manchester’s main square.

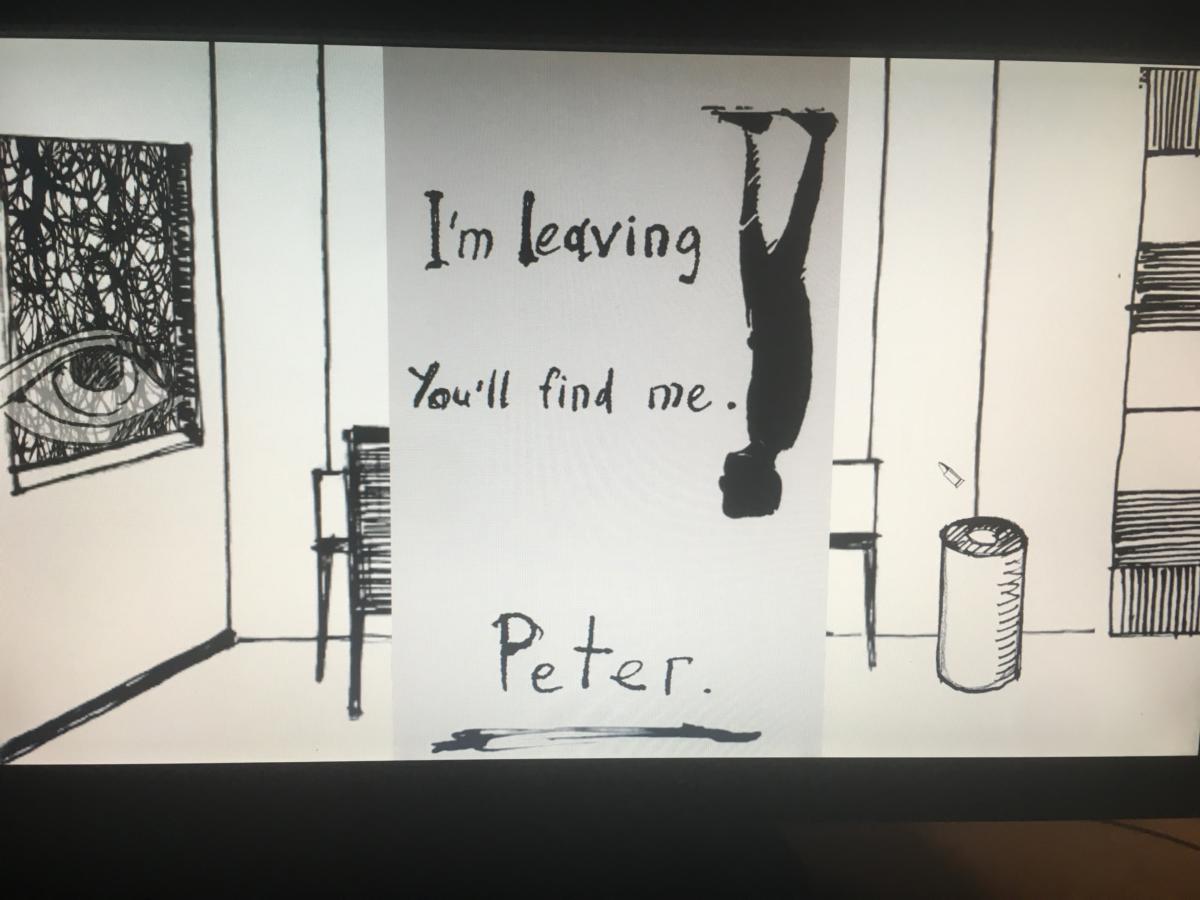

As I mentioned before, the exhibition manages to talk about the refugee crisis and the migration politics in a surprisingly non-cliché way. Obviously, the notion of the border can be seen as a connection between the different works, but also because it is one of the main themes of the exhibition, it functions very well. The famous Austrian artist, Oliver Ressler’s black and white animation (Emergency Turned Upside-Down, 2016) touches upon the notion of borderlines, migration routes and changing circumstances in geopolitics in a playful, yet sensitive way – the well-known work finds its place at the exhibition and gets into dialogue with projects that are focusing more on local issues. Like the work of the Polish artist Piotr Wysocki, who documented the border controls at the checkpoint of Eastern Poland. In his installation (The Border, 2011) we have to peer into something which resembles a suitcase, as if examining the transported goods ourselves: it is disturbing in its simplicity, as it reflects on the hidden violence happening at these checkpoints. Artur Żmijewski’s 16 mm film about The Jungle (Glimpse, 2016-17), which was the largest refugee camp in France in Calais, tends to belong to the more aesthetizing works about the refugee crisis, taking a bit advantage of the situation, yet Marina Naprushkina’s – Berlin based Belorussian artist – video (German for Asylum Seekers, 2016) could have been seen as its counterpoint with its minimalistic visuality. An extraordinary alphabet – “A” as Arbeit (work), M” as Maßnahme (measure) and mini-job, “W” as warten (wait) – was running on the screen, showing the words and expressions one has to learn in order to live and work in Germany. Striking in its simplicity, Naprushkina’s alphabet deals with the politics of language and the struggles of everyday communication.

It is difficult to see the chapter Conflict separately, as almost every work deals with a certain kind of conflict situation, be it military or personal. But the installation of Hito Steyerl (The Tower, 2015) found its right place in the main area of Cepelia and is one of the highlights of the show. The video tells the story of an IT company in Kharkiv which is at the same time deals with real estate and creates shooter video games, based on fictionalized historical events. Steyerl’s both visually and textually dynamic work operates on several layers: through the presentation of this maybe not so unusual company and the usage of documentary materials blended with fiction, she draws attention to the actual military conflict happening “at the doorstep” (as the exhibition text promptly wrote) of Kharkiv. The video is not long, but one has to watch it several times to understand the hidden parallels between the different layers and narrations.

Steyerl’s piece is closely linked to another important work of the show: on one hand because of its visual and thematic usage of video games and on the other because of the thematization of the military conflict in Ukraine. In Marginal Act’s (Mykyta Filonenko) video game, Vasilisa (2015), the player has to guide an older woman from her apartment around Kharkiv to find his missing husband who disappeared during the war. The visuality of the video game with its black-and-white harsh drawings reflect exactly on the brutality of these everydays, which became a normality in that disturbed area for a long period of time. Yet, for me, it was not possible to find the older women’s husband. I tried several times, but got lost in the fictional apartment, like in a labyrinth. A sense of hopelessness occurred, and even though it was only a video game, I felt physically powerless. As I was on my way to leave the exhibition I encountered the Azerbaijani, Paris based Babi Badalov’s sarcastic yet quite depressing poems on his mural installation which filled up the last room (Untitled, 2018). His piece brought me back to my own reality – a Hungarian citizen, being in Warsaw, learning about Ukraine, Poland and other neighbouring countries. As I left Cepelia and entered the street from the basement, I looked back to the “Has not died yet” sign. I thought of Vasilisa’s husband. Did he survive?

This article was written in the frame of East Art Mags residency program, with the kind support of Erste Stiftung (Vienna) .The author would like to thank Gergely Nagy (artportal.hu), Karolina Plinta (SZUM / BLOK) and Balassi Institute in Warsaw for their help.

Imprint

| Artist | Babi Badalov, Oksana Briukhovetska, Oleksandr Burlaka, Oleksiy Bykov, Davyd Chychkan, Phil Collins, Kseniya Hnylytska, Nikita Kadan, Taras Kamennoy, Gal Kirn & Fokus Grupa, Dana Kosmina, Marginal Act, Marina Naprushkina, Valentyna Petrova, Aleka Polis, Serhiy Popov and Mykola Ridnyi, Oliver Ressler, Santiago Sierra, Anna Sorokovaya, Hito Steyerl, Łukasz Surowiec in collaboration with Marta Romankiv & Oleksandra Ovsyannikova, TV Kryzys, Piotr Wysocki, Alina Yakubenko, Florian Yuriev, Artur Żmijewski |

| Exhibition | 10th Warsaw Under Construction Festival. Neighbours |

| Place / venue | Cepelia Pavillion, Warsaw |

| Dates | October 13 – November 11, 2018 |

| Curated by | Anna Kravets, Yustyna Kravchuk, Oleksii Radynskyi, Ruslana Koziienko, Serhiy Klymko, Vasyl Cherepanyn, Nataliia Neshevets, Oksana Briukhovetska, Ganna Tsyba, Szymon Maliborski |

| Website | wwb10.artmuseum.pl/ |

| Index | Aleka Polis Alina Yakubenko Anna Kravets Anna Sorokovaya Artur Żmijewski Babi Badalov Dana Kosmina Davyd Chychkan Flóra Gadó Florian Yuriev Gal Kirn & Fokus Grupa Ganna Tsyba Hito Steyerl Kseniya Hnylytska Łukasz Surowiec in collaboration with Marta Romankiv & Oleksandra Ovsyannikova Marginal Act Marina Naprushkina Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw Nataliia Neshevets Nikita Kadan Oksana Briukhovetska Oleksandr Burlaka Oleksii Radynskyi Oleksiy Bykov Oliver Ressler Phil Collins Piotr Wysocki Ruslana Koziienko Santiago Sierra Serhiy Klymko Serhiy Popov and Mykola Ridnyi Szymon Maliborski Taras Kamennoy TV Kryzys Valentyna Petrova Vasyl Cherepanyn VCRC Yustyna Kravchuk |